A new book by Giorgio van Straten, La Ribelle. Storia straordinaria di Nada Parri, Laterza, 2025 (forthcoming in English with Other Press, in 2026) recounts a little-known yet remarkable story that invites us to put aside the rhetoric and contentions over historical memory and reconsider the values and ideas that propelled resistance in the past.

A new book by Giorgio van Straten, La Ribelle. Storia straordinaria di Nada Parri, Laterza, 2025 (forthcoming in English with Other Press, in 2026) recounts a little-known yet remarkable story that invites us to put aside the rhetoric and contentions over historical memory and reconsider the values and ideas that propelled resistance in the past.

For Italy’s post-war generations, April 25th is a very symbolic date marking the Allied Army’s defeat of Fascism and the Nazi occupation, as well as the role of the Italian Resistance. The courage and determination of the Partisans have always been a source of inspiration and respect, as the historian Carlo Greppi explains: “We celebrate the liberation from twenty years of dictatorship and wars, five years of world conflict, twenty months of civil war. Freedom was conquered, with and without weapons, by a large minority: an army of volunteers, men, and women. It is the highest moment in the history of Italy, and it must inspire us”.

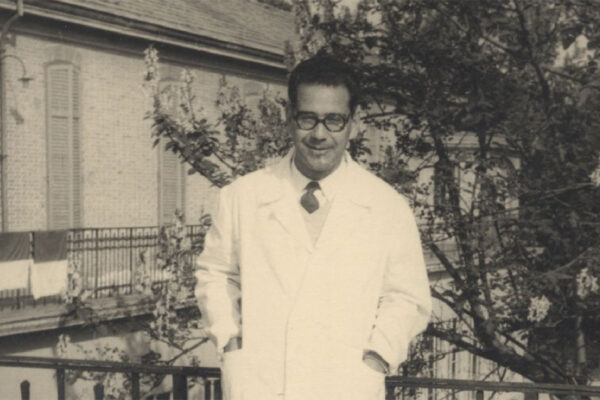

Giorgio Van Straten, whom many of us fondly remember for his tenure as Director of the Italian Cultural Institute (2015 -2019), weaves his novelistic skills with his passion for historical investigation, ushering us into the life of Nada Parri, one of many unsung protagonists of the Resistance.

From her early years, Nada Parri, “the rebel,” waged one battle after another, straddling the line between personal and collective experience. Her humility and unwavering commitment to truth and justice serve as a beacon of hope that every generation places in the future, against all odds.

In the novel, Nada is twenty, has a two-year-old daughter, and is alone. Her husband left as a volunteer for the Italian war in Ethiopia. Her family is far away, and she knows almost no one in the new city where she lives. Hermann is nearly forty years old, has a family in Germany, is a non-commissioned officer in the Wehrmacht, and hates Hitler. They meet by chance on a winter afternoon in a small Tuscan town and fall in love. Together, they decide to escape; she from the wrong family, and he from an army that, once an ally, has become an occupier. They flee to the mountains and join the partisans. They risk their lives and participate in the liberation of Parma, convinced that the future is on their side. But the future takes many unexpected turns. Van Straten compassionately follows Nada’s and Hermann’s footsteps, chasing people, documents, objects, and photographs, allowing the past– or versions of the past–to resurface with great emotional impact, beauty, and unanswered questions.

From the book’s prologue:

Sometimes you meet people on the street, and even though you’ve never seen them before, you recognize them. You stop, you watch them go by, and you are convinced, by something in their eyes, or in the movement of a hand, or in a slightly limp gait, that they have a story to tell you.

When you meet people like that on the street, even if you stop and look at them, they keep walking, because that’s what you do on the street: you move forward without uncertainty, you enter a doorway, you get into your car, you answer your phone, you look up at the sky to see if it’s going to rain.

In short, those people don’t pay attention to you. For that matter, why should they? They don’t even know you. So their stories won’t be told and will be lost. Or at least you won’t be the one to pick them up, even if you were ready to hear them.

Sometimes, on the other hand, you meet people in books, and then their stories remain there, at your fingertips, even if they are just hinted at, a light stroke, and many readers, like people walking down the street, pass by. But you, on the other hand, get stuck in one spot, in front of lines that force you to take those hints, those skeletons of stories, those sketches of characters, indeed of people, and carry them with you

Something, a minor detail, usually, a side note, makes them suddenly alive, real, like a passerby on a street in your town. Only they stop and, if you feel like listening to them, they tell you their story.

Sometimes, you can find these people in other countries, on other continents, surrounded by unknown geographies; sometimes, they are not your contemporaries, and you meet them in the past, immersed in a different history. The further away they are in time or space, the more effort they will require for those who want to tell their lives, and sometimes it will happen that not enough elements will be found to reconstruct them, and you will find that they are lost forever. But it may also happen that the search succeeds and becomes a path and, step by step, becomes your own journey. Then there will be two stories worth telling.

I first met Nada Parri in a book, ‘The Good German,’ by Carlo Greppi, about deserters on the Italian front in World War II. From a numerical point of view, it is a very small phenomenon: maybe a thousand people out of hundreds of thousands of soldiers, even though we are talking about a retreating army in a war, by then, lost. I thought it should not be easy to desert in a country where a substantial part of the inhabitants, starting with those who had gone up into the mountains to fight them, showed strong hostility toward the Germans. I thought it was very risky to leave the army of a state under a dictatorship, where dissent was paid for with one’s life.

I first met Nada Parri in a book, ‘The Good German,’ by Carlo Greppi, about deserters on the Italian front in World War II. From a numerical point of view, it is a very small phenomenon: maybe a thousand people out of hundreds of thousands of soldiers, even though we are talking about a retreating army in a war, by then, lost. I thought it should not be easy to desert in a country where a substantial part of the inhabitants, starting with those who had gone up into the mountains to fight them, showed strong hostility toward the Germans. I thought it was very risky to leave the army of a state under a dictatorship, where dissent was paid for with one’s life.

Whatever the reasons, there were very few deserters. But this, if it increases the collective responsibility of a people who only minimally and very late rebelled against Hitler, not only does not reduce, but on the contrary exalts the courage of those who made that choice and often suffered the consequences, sometimes immediately after fleeing, but others even long afterwards, because deserters never enjoy a good reputation when they return home.

Among these thousand soldiers, there was a man in his late forties, blond as befits a German, a non-commissioned officer in the Wehrmacht, whose name was Hermann Wilkens and who was stationed on the Tuscan coast, in Marina di Carrara to be precise, after September 8, 1943. His radical and courageous choice ended up disrupting not only his life but also Nada Parri’s.

The book devoted little more than a page to Hermann and Nada. Still, that page was enough to plunge me into a story that I could no longer forget, a tragic and heroic personal affair, that intersected with the events of History. In order to tell it, one must also talk about the war, fascism, the liberation struggle, the condition of women, and the Italian Communist Party.

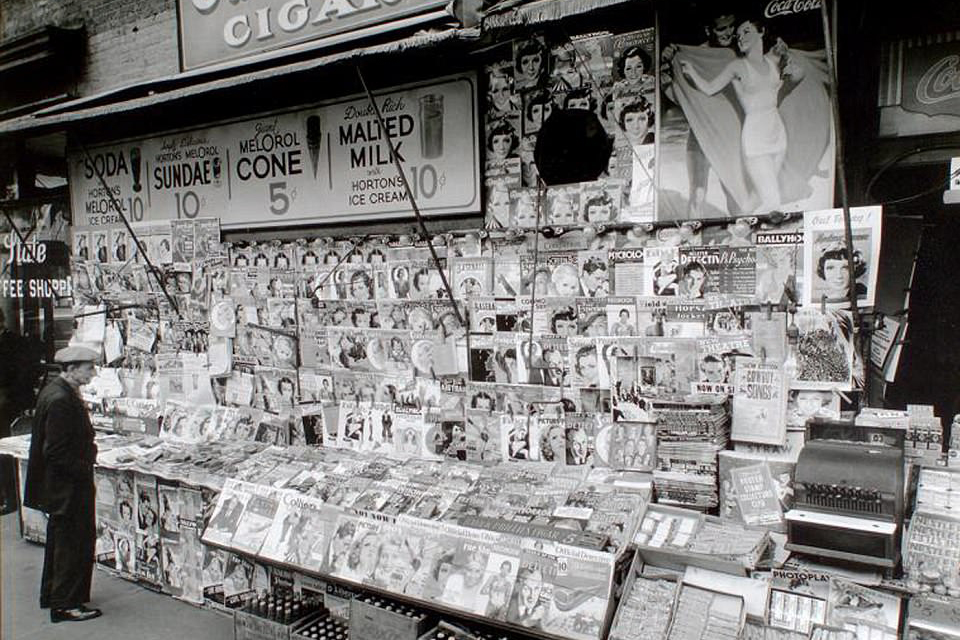

Images: Nadia Parri, and Brigata Garibaldi “Bianconcini”, 1944