Nurith Aviv: filmer la parole. Edited by Claire Buchbinder, Marianne Dautrey, and Nathalie Georges-Lambrichs. Exils Éditeur (2025).

A new book celebrating Nurith Aviv’s films has just been published in France. It will be available in New York at the Albertine Bookstore and Anthology Film Archives on the 22 and 23 of April. We have translated and published with the author’s permission a few excerpts for our readers (translation by Yuval Jonas and Marin Diz).

An interview by Hélène Molière, Myriam Leibovici, and Pauline Goudot (March 2024)

Why choose to make an entire film about a single letter of the alphabet, the consonant R?

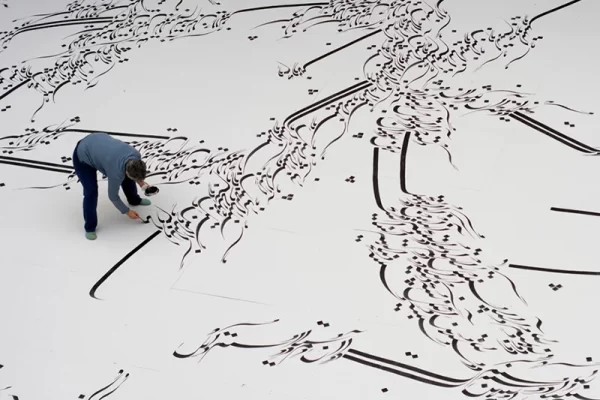

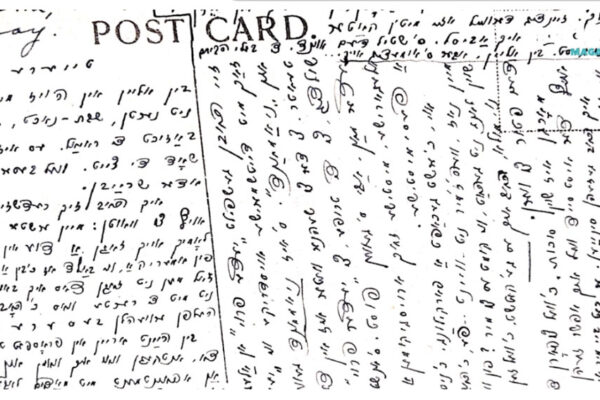

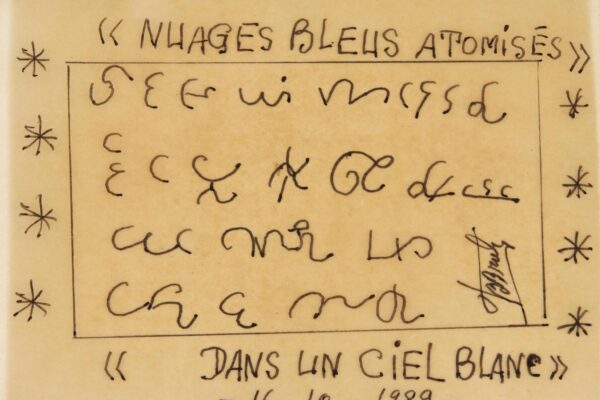

Even as a child, the sounds of the letter R troubled me. Around me, people spoke a multitude of languages with very different accents. I heard the R in the middle of my first name, Nurith, pronounced by each in a thousand and one ways. I couldn’t imagine that it was the same letter of an alphabet I didn’t yet know. I felt that to pronounce this R, the body, the mouth, and the tongue were more involved than to pronounce the N or the T in my first name; it was more sensual, more carnal. The R sometimes even has an animal quality, a roar, a purr, a snort. According to linguists, it’s often the sound whose pronunciation children acquire last. I think there’s no other letter that wanders like this inside the mouth: rolled on the tip of the tongue or coming from the back of the throat, hard, soft, or barely perceptible. In German, the language my parents spoke to me in, you often don’t hear the R at the end of the word. For me, for example, the word Oper (opera) sounded like opa (grandfather). I remember trying to play Scrabble with my parents. I didn’t know how to write German, I wrote it phonetically, and I can still hear their bursts of laughter elicited by a missing or extra letter. In Portuguese, the R is trilled—pronounced gutturally—at the beginning of the word, and rolled in the middle. I remember the rolled R of my father’s Russian friend, and I can still see his tongue beating endlessly against the roof of his mouth. Or the Hungarian R of my uncle, my aunt’s husband, whose sound was so strange and fascinating. I realized much later, in 1983, while I was in China shooting a film, that there is no R at all in Chinese. And that in Asia millions of people speak languages in which the R sound doesn’t exist, for example, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and others. Opera singer Laurent Naouri explained to me that in the world of opera singing, there are different opinions about how to sing the R in French, with the trilled R or the rolled R. He himself distinguishes at least four possible pronunciations. Already in my first film on languages, From One Language to Another, in 2003, the poet Agi Mishol recounted how, at the age of five, she had spent hours in front of the mirror to lose her Hungarian rolled R and adopt the Israeli guttural R. This guttural R probably comes from Yiddish, the mother tongue of those who renewed Hebrew at the very beginning of the 20th century. Another friend, of Argentinian origin, described the exact same scene in front of the mirror. I then thought it was a subject worth exploring. But it took making my latest film, Words that Remain, in 2021, for me to understand how to make this new film on the sound of the R. In Words that Remain, people recount childhood memories linked to words from languages they don’t or no longer speak, and which have remained stuck in their ears.

%0