In loving memory of Bruce and Francesca Slovin.

I am sitting in the building that I visited thirty-something years ago with Francesca and Bruce Slovin. They were elated at the sight of the beautiful historic façade on 16th street and the availability of commercial higher edifices in the back, on the 17th street side. A challenge they had nurtured and imagined for some time was now materializing: finding a home where Jewish libraries and archives could amalgamate around YIVO, the Institute for Jewish Research, and enter the digital era.

I knew Francesca from The New School and met Bruce with her. They were a monad, propelled by ideas, roots, and aspirations that appeared to me a bit a-systematic and somewhat capricious yet held together by their warmth, wit, and unwavering care. Our relationship consolidated over a plate of scrambled eggs they prepared on a playful Sunday morning at their home, and which, we agreed, tasted exactly like those all three of us claimed to remember from our childhoods.

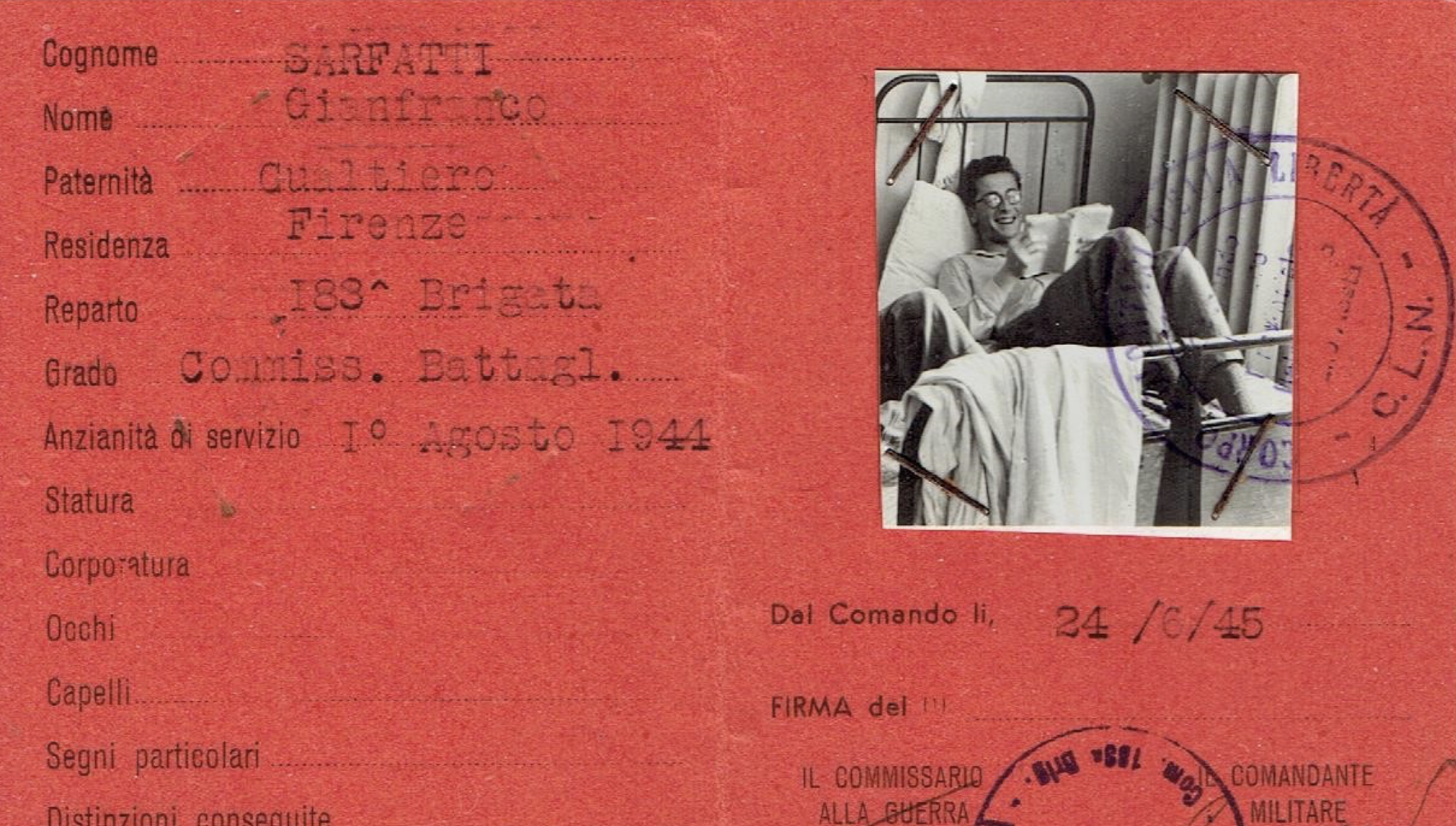

Bruce showed me a picture of himself, at 15 or 16, on the street of Brooklyn where he grew up, with a mixture of awe for what he had built and nostalgia for what he had left behind. Francesca, who came from an affluent family of intellectuals and stood undecided between academia and politics, mirrored her husband’s feelings with her own nostalgia for long-lost ideals and what was known in Milan as the “Via Gluck”. They were both devoted to bringing the past into the future with a spirit that reminded me of Yingl Tsingl Khvat, the boy who brings his town into an imagined winter’s splendor.

Bruce Slovin was born in 1935. His parents owned a manufacturing business in Brooklyn. After attending Jewish and then public school, he entered university during the transformative years that followed Brown v. Board of Education. He graduated from Cornell University, Harvard Law School, and Columbia Business School.

When I met them, Bruce and Francesca had been involved with YIVO for some time and had already embarked on the idea of making the historic Vilna-based organization the center of a consortium of Jewish libraries and archives, representative of the vast geography of Jewish culture. The arrangement they envisioned was that of a collective, conceived to prioritize the common good so that each partner could fully dedicate itself to the development of its field, and collaborations could flourish. For the time being, they pragmatically postponed the conversation on the history and dilemmas of self-governance.

During the renovation that merged four buildings into one, Bruce and Francesca became busy conceptualizing the union of five organizations with similar practical needs but profoundly different histories and personalities. I followed the process as a friend and, eventually, as an advisor and staff member. Bruce delighted himself like a bee in honey, candidly spreading enthusiasm while listening to architects, technicians of all kinds, pundits, scholars, and philanthropists, each with a novel idea of what this place could or should be. “It’s the largest repository of Jewish history outside of Israel!” he concluded at some point. When I heard him for the first time, explaining the idea to a small group of awe-struck donors, I played the words back in my head, trying to figure out if he was imagining a home-grown version of Israel on a small scale, a unified entity where the historical past of Jews from all over the world would be represented in one space and time. Back then, it struck me as strangely symbolic that this “maquette” was taking shape shortly after the assassination of Itzhak Rabin and the end of his era.

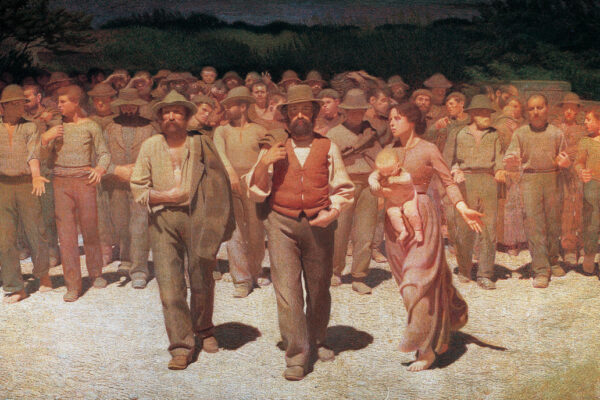

The unification of the Jewish past amidst a concerted social effort to expand institutional Jewish life in New York (the Museum of Jewish Heritage, Makor, and the JCC came into being during the same years) went hand-in-hand with the anxiety for the decline of interests and inclinations that had been, until that point, unquestionable in the Jewish world—education and social justice. The bookends to this flurry of might and fear were two works that bracketed a decade: Yosef Yerushalmi’s Zakhor (1982) and Ammiel Alcalay’s After Jews and Arabs (1993).

By the time the construction was completed in 1999, the library-archive had grown to include a theater, galleries, a café, a bookstore, and a series of facilities that made everything puzzling and exciting. Bruce and Francesca were idealists with uncanny practical skills. They knew that coming to life did not mean to succeed, but also knew that life had to come first.

And so the Center for Jewish History came into being—history cast in its name like an amulet—a century-old ambition that, as Yerushalmi noted, was fundamentally at odds with the American Jewish psyche. For the first seven years, as commanded by the Torah, Bruce manned it, cheered it, tested it, infused it with curiosity, hope, courage, urgency, and a pinch of tragic irony that he held dear and very few around him understood. It was an adventure inscribed in the rhymes of Tsingl Khvat.

I have no doubt that life was what Bruce and Francesca put into this project. Life with its mess, its contradictions, and its being there to transform itself and the surrounding world, the world Francesca left in 2017. Two volumes testify to her reflection on creating the Center with her husband: a book on Aby Warburg, who conceptualized one of the most eccentric and influential libraries of the 20th century, and one originally entitled In the Beginning, her own ode to the early dream of Israel. Bruce followed the writing of the books, projecting onto them the power to provide answers or at least appease the doubts over the way this new life was taking its own course, far away from what they had envisioned. The amulet, the dreams, the books remain, and with them life—with its unmistakable flavor of everybody’s childhood eggs.

When he departed last month, Bruce left a magic lantern, which may today look like a silent piece of metal, but could one day glow in the echoing embrace of his laughter.

Image: Ahuva Shweiki, Still Life, oil on canvas