Elisa PederzoliElisa Pederzoli is in charge of the Library and historical archive of the city of Crevalcore (Bologna). She received her PhD in Literary and Philological Cultures from the University of Bologna (2019), with a thesis in History of Books and Publishing. Until 2020, she has worked at the Biblioteca Estense Universitaria in Modena, where she collaborated in the preparation of the exhibition catalogue on the exhibit: Angelo Fortunato Formiggini. Laughing, Reading and Writing in Early Twentieth-century Italy. She is a member of the editorial staff of the magazine "TECA" and an expert in archival, bibliography and library sciences at the University of Bologna.

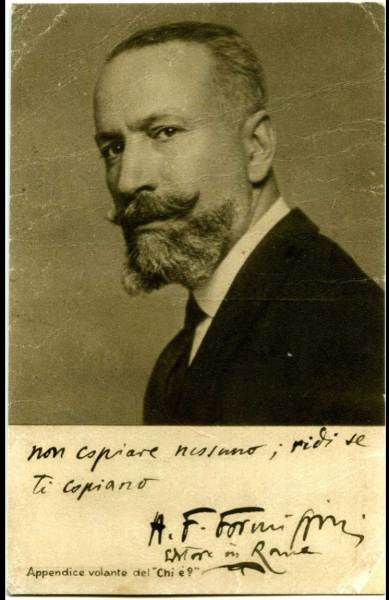

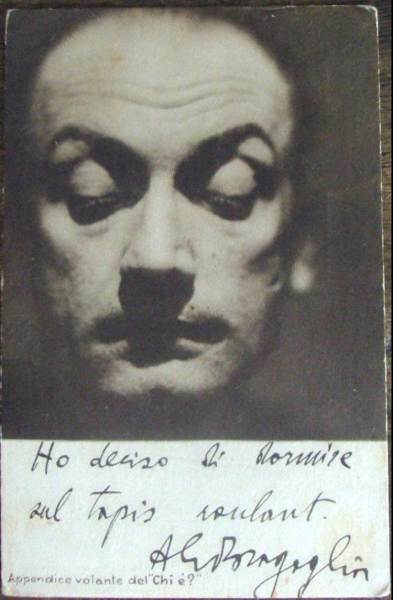

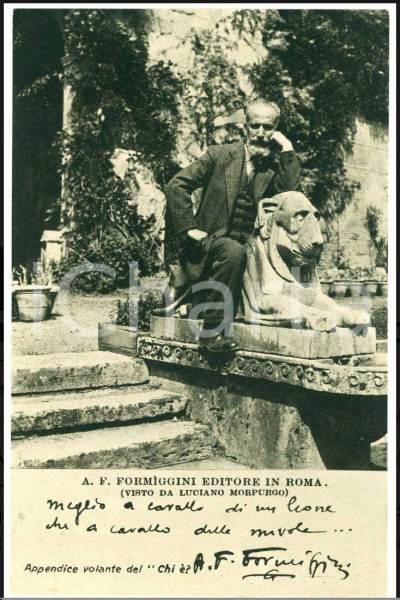

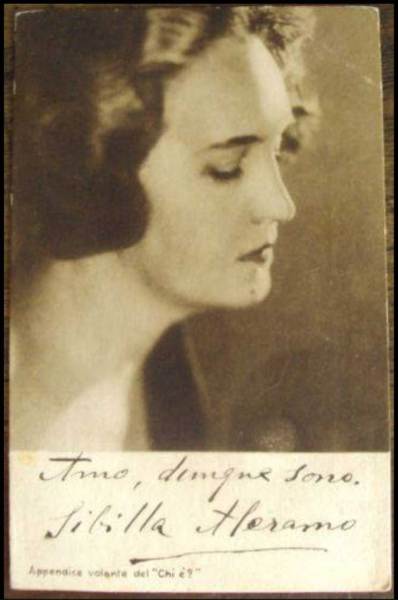

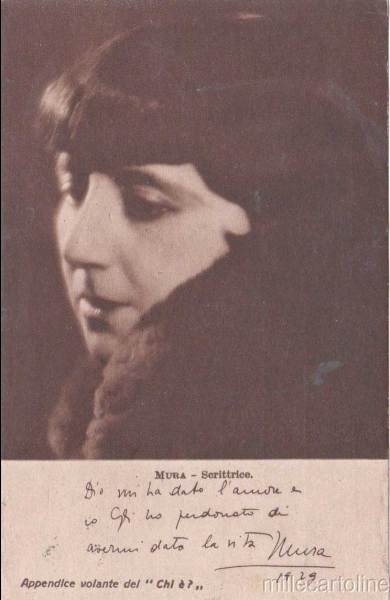

In an era in which advertising was not yet an industry but rather an incipient trade entrusted more to imagination than anything else, the Italian publisher Angelo Fortunato Formiggini invented the “Cartoline parlanti” (talking postcards). They were conceived as a promotional tool for the 1928 launch of Formiggini’s Chi è? Dizionario biografico degli italiani d’oggi, which was the Italian equivalent of the renowned British Who’s Who? series. The Cartoline included the authors of the publishing house along with other personalities listed in the biographical dictionary.

A brilliant publisher, Formiggini started running his business in the first decade of the twentieth century in his hometown of Modena. He then moved to Genoa and finally to Rome in 1916. The wit and refinement of his publications, as well as his pursuit of new, captivating ways to promote Italian books and culture in Italy and abroad, gained the respect and appreciation of scholars of the likes of Giovanni Pascoli, Antonio Gramsci, Giuseppe Prezzolini, Arthur Livingston, and Harry Nelson Gay.

Among his early creations was the Circulating Library, which he launched in Rome in 1922 as an open cultural network among writers and intellectuals in Italy and Europe. This peculiar library followed the established tradition of Anglo-Saxon circulating libraries, which grew between the XVII and XVIII century and spread all over Britain by the beginning of the XIX century. Its aim was to make available to the public the publications received for Formiggini’s most famous bibliographical magazine, “L’Italia che scrive” (ICS). The library acquired 40.000 volumes in a few years and was very popular among intellectuals as well as middle class readers, who appreciated the fair subscription fee and the variety of the collection.

The Formigginis were a family of court jewelers with a long history in Modena. A secular man, he had refused to abjure his religion in 1931 when membership in the Jewish community became mandatory, and was keenly sensitive to how newly formed national cultures redefined minorities. Unfortunately, Formiggini’s career was brutally interrupted by the promulgation of the Racial Laws that, in 1938, prohibited him from running his publishing house.

Unable to live without his work and wishing to make a statement against Fascist racism, in 1938 he committed suicide by jumping off the Ghirlandina tower in Modena.

The Fascist government was concerned that his act would smear the image of the Regime and forbade any official notice of his death. His widow, Emilia Santamaria Formiggini, could not publish his obituary and was forced to hold the funeral in secret. The Regime’s damnatio memoriae against Formiggini sank into oblivion not only his death but also his life and his many remarkable achievements. Only in 1980 his archives were rediscovered and duly studied.

As an enthusiastic bibliophile, Formiggini paid meticulous attention to every detail of his books, from the covers to the images, size, and proportions, believing that the refined appearance of each volume would convey the high quality his publications.

However, he had to confront production problems and competition in a market that had grown exponentially after the unification of Italy. The diffusion of steam-driven printing presses from England to the rest of Europe and the speedy increase of literacy led to the mass production of affordable books. The competition among Italian publishers was fierce, each seeking the best way to attract readers and shaping national learning, which was of paramount importance in the newly formed country. It was in this atmosphere that Formiggini began to research promotional strategies, coming up with the idea of the Cartoline parlanti.

Always keen on novelties from abroad, Formiggini realized that Italy was one of the few modern nations that lacked a Who’s Who? series, a biographical dictionary of the most distinguished personalities in all fields. Who’s Who? was originally conceived in 1849 by Baily Brothers in England. The first editions provided a list of notable people like bishops and members of parliament. Subsequently, in his 1897 edition, Adam Black enriched the biographical details. After that, in 1889, the Chicago-based publishing house Marquis Who’s Who began to release Who’s Who in America, A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Living Men and Women, which quickly gained popularity. Similar publications followed in Germany (1905), New Zealand (1908), Canada and Denmark (1910), Sweden and Norway (1912), and Australia (1923), France (1953).

Inspired by that anglophone tradition of Who’s Who?, in 1928 Formiggini published the first edition of the Chi è? Dizionario biografico degli italiani d’oggi. The five hundred pages volume contained a list of brief biographies of notable Italian men and women (as a courtesy he did not list the ladies’ year of birth). First came the “Gerarchie,” members of the Italian political elite, followed by all other categories. In his introduction, Formiggini himself stated that the selection was accurate, though arbitrary: following the British edition, he “took into consideration political, religious, civil and military hierarchies together with academic personalities.” He explained that being part of the Chi è? “was not a celebrity badge, nor should be regarded as a reason for pride. It was simply a sign of notoriety.”

The collection of information was an affair of its own. Formiggini sent a form to each person included in the survey asking to fill out personal data and “the most essential biographical and bibliographical information” about themselves, paying attention “not to use adjectives or personal opinions.” However, this recommendation was hardly enforced and the partisan nature of many entries became the target of criticism.

In order to create a series just like those published abroad, Formiggini made sure to update the publication every year, which sets his series apart from the previous project by the scholar and librarian Guido Biagi who had published a similar list in 1908. However, as Formiggini himself noted, Biagi’s work never achieved significant success, and the publication was soon interrupted.

Formiggini was proud of the new endeavor and, considering himself not only the publisher but also in a certain way the author of the Chi è? he used the preface to the first edition to directly address his audience:

“Dearest Readers, you are too clever not to understand that the book lying in front of you represents in embryo a new «national institution»: every great nation has long had its Who’s Who?, its Wer Ist’s?, its Qui êtes-vous?; and our country needed to have a national guidebook destined to find its place in all the libraries of the world, next to its colleagues of other nations, on the table of all intelligent rulers, in newsrooms, in public and private offices and wherever there is an interest in knowing the essential data on the best known Italians.”

Formiggini understood that this innovative project required an equally creative promotional strategy to capture the audience’s interest and attain widespread distribution. Hence came the idea of the Cartoline parlanti, featuring some of the Chi è? ‘s personalities in a series of fancy postcards. The cards were meant to advertise the book through the personal networks of those whose visibility they enhanced.

He then sent each of the contributors a newsletter informing them of his new plan:

“Esteemed author, for a long time, I’ve been flirting with an idea that I think may work. I want to make a talking postcard for each of my Profiles, that is, to reproduce exquisitely with chalcography (!) your photo-portrait and under it place a very concise biography, of a hundred words at most. Would you be so kind as to provide your own brief profile to me?”

Formiggini’s idea was not entirely new. Authors’ portraits were already used for promotional purposes before the era of mass distribution of goods. In the Middle Ages, manuscripts often featured the authors’ initials decorated with miniatures of their images.

In the age of printing, portraits of authors became increasingly more common. Xylographs of initial letters included pictures of the author or scenes of dedication, drawing on the manuscript tradition. In the 16th and 17th centuries, portraits became a distinct feature of printed books. Mottos were also common in early modern books accompanying the portrait of the authors to epitomize their outstanding intellectual and moral traits.

Formiggini’s understanding that the authors’ personal image could be used for promotional purposes was thus also informed by his expertise and love of ancient books. Combining these historical inspirations and the modern concept of elite behind Who’s Who, he decided to ask each of his contributors for “a fresh and artistically perfect photograph and a short characteristic autograph” with a distinguished shape and size.

While gathering the materials for the postcards, Formiggini addressed some of his correspondents with great meticulousness. For example, he wrote to the poet and critic Fausto Maria Martini:

“My Dearest and kind friend, this is to remind you of the promise to send me a beautiful picture of yourself and an expressive autograph, separately written on white paper the size of a postcard, that is 9 cm., and 3 1⁄2 cm. high. The one that you have shown me would be fine.”

The same instructions were given to his friend and writer Corrado Alvaro:

“Dear Alvarone, this is what I ask you: […] send me a beautiful photograph of yourself. It doesn’t matter that you are ugly, as long as the picture is really beautiful. [And] send me an expressive autograph that represents you, written on a piece of white paper the size of a postcard, that is 9 cm., and 3 1⁄2 cm. tall.

Alvaro answered instantly by delivering the requested materials to the publisher, but Formiggini was not entirely satisfied:

“The picture is beautiful, but there’s one problem: it is crumpled, perforated, and stained. I’m afraid this can damage a good reproduction. If the plate still exists, please, get a new copy to send me in exchange for this one. The autograph is just fine but bear in mind that it will be reduced to the width of a postcard, that is a quarter reduction. It would be useless to rewrite it smaller because the camera itself will do the reduction process, but if you think that your downsized writing would be hardly readable, you can make a new 3 1⁄2 – 9 cm. card. From that sample, the reproduction will be precise.”

He deemed precision necessary because the printing process for the postcards was difficult and expensive, as Formiggini complained with his friend and correspondent Luigi Tonelli:

“Dear Tonelli, the “postcards stuff” has made me sweat for years, and I still cannot get over technical problems. In order to use rotogravure to make the postcards, I would have to print too high a run, which would be impossible to sell. I tried with typography, then. Here’s a sample enclosed, but I’m not satisfied with the aesthetic result. Perhaps it will be necessary to use a heliotype like the cute portrait that you liked so much. It will be insanely expensive.”

Formiggini was a talented publisher as well as a businessman, and he had to make ends meet. Rotogravure was based on the transfer of ink from designs engraved into the printing plate. It could print a rich range of tones, making it ideal for reproducing photographs in large quantities. On the other hand, Heliotypy involved transferring pictures directly from photographic negatives to hardened gelatine plates from which impressions were reproduced on paper. Both printing techniques were expensive and would have required Formiggini to print large numbers of each postcard in one batch to reduce the costs. In the end, Formiggini chose the rotogravure. The authors would have to pay for their own postcard if they wished to acquire copies; furthermore, to make it sustainable, Formiggini would also need to promote and sell the postcards as stand-alone items.

From the very moment of their creation, the talking cards went beyond their intended role. Formiggini envisioned their circulation not solely through sales and distribution but recommended that all authors use them for private correspondence, setting the example by sending them instructions on his own talking card…

There was, however, a problem. The preliminary project comprised a picture, a motto, and a brief biography, but that seemed to take up all the space on the card. In contrast, Formiggini needed to allow space for personal writing. In order to leave enough room to write, something would have to be taken off the postcard. After consulting with one of the authors, Vincenzo Errante, Formiggini concluded that the biography was redundant: the postcards were meant to promote the dictionary, not to replicate its content. Errante also suggested the addition of a line capturing the essence of a person’s career. Foreseeing the commercial implications of individual ambition and collective consensus, he wrote:

“We need to “take advantage of” human ambition. These two lines would give greater value to the document, that would appear to be more “editorial” than “private”; and I think it would facilitate the sale.., at least by each person involved. […] You must realize that most of them are images of writers, musicians, painters. I mean, people who care about promoting themselves. And you gave the full biographical data into Chi è?. So, yes, this way, the talking postcards would be an authentic “flying addition” to Chi è?.”

Formiggini considered all of Errante’s suggestions carefully. The postcards’ final version included the photographic portrait, the motto with signature, the full name, and a mention of each personality’s trade. Problems, however, were not over. The journalist Arnolfo Santelli complained to Formiggini about the misspelling of his name “Arnoldo” instead of “Arnolfo,” and he wanted it corrected right away. To make his point, he used his own postcard on which the name was corrected twice in his own handwriting.

The writer Pittigrilli also complained. In the first version of his postcard, Formiggini had indicated his real name, Dino Segre, and the author immediately objected:

“Dear Formiggini, why did you put Dino Segre on the postcard? Why do we perpetuate the stupid habit that has afflicted Gandolin, whom no one mentions, without adding a bracketed “Vassalli”? […] How irritating! If you can remake the postcards with only Pitigrilli, I’ll buy a few hundred.”

Formiggini appeased the writer by printing several revisions, which didn’t stop Pitigrilli from making a fuss on his photograph and demanding more changes.

These requests for corrections suggest that Errante’s intuition was correct. By featuring portraits of public personalities, the talking cards immediately acquired a second use beyond the promotion of Chi è? and the publishing house. They became a way for the writers, musicians, politicians, etc., listed in the dictionary to promote themselves by using the postcards for their private communications. The writer Guido Stacchini – also listed in Chi è? – clearly understood the double function of the Cartoline in his letter to Formiggini:

“Dear Formiggini, I received the postcard informing me of the new ‘postcard-photographs’ project. I would be very grateful if you could send a hundred of them to Viareggio, where a stand has been set up to sell my books during the Fair. It will open on the 14th of the current month. However, you should send them immediately by express courier, as they must be in Viareggio no later than the 13th […].”

Stacchini’s letter demonstrates that, although the postcards were meant to advertise Chi è?, the author wanted “his postcard” for his own advertising purposes at the Viareggio book fair, believing that they would have appeared novel and attractive to the public.

Formiggini too, was aware of the potential of his creation. In the first edition of Chi è? he placed what we might call an advertisement for the advertisement on the verso of the title page:

“Chi è? Dizionario degli Italiani d’oggi will be accompanied by a flying addition, that is, a collection of autographed photographs, printed with the most exquisite modern technique on special Cartoline parlanti which […] will be suitable for private and commercial correspondence […]. A list of the available postcards will be sent on request.

The operation did not last long. For the editions of 1931 and 1936, no new talking postcards were printed.

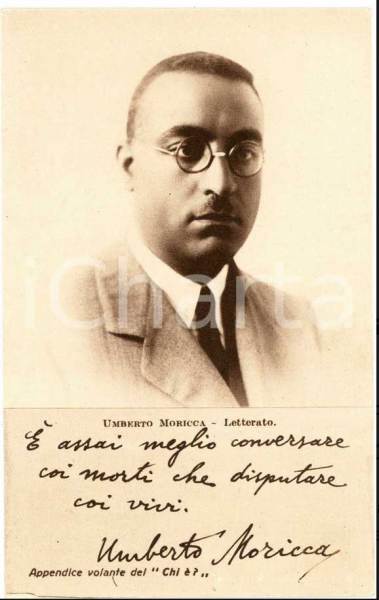

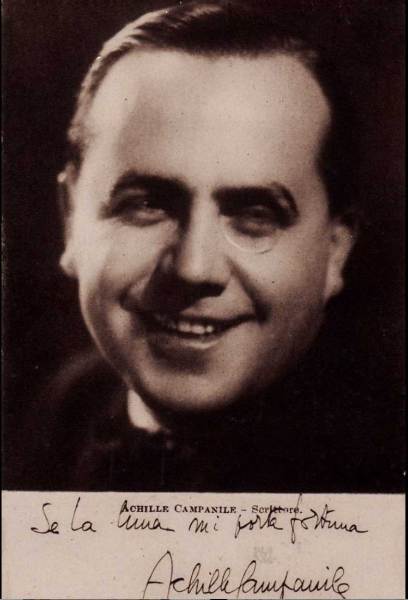

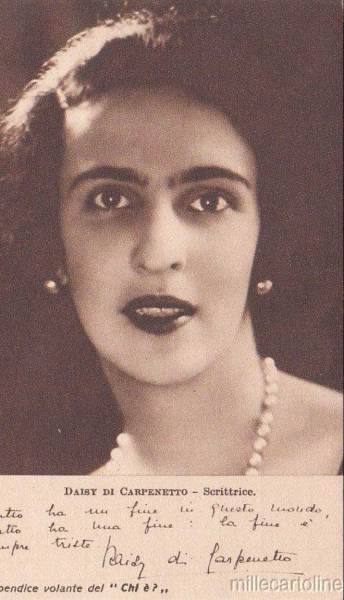

It is possible that, despite their cultural allure, the Cartoline parlanti were way ahead of their time and not immediately sustainable. Clearly however, their potential was perceived by the large number of authors who asked to be featured in the series. After the first test run of fifteen postcards in 1928, they became so popular that by October 1929, there were seventy-three. They included personalities such as Giuseppe Antonio Borgese, Achille Campanile, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Giovanni Papini, Alfredo Testoni and Vito Volterra. Since Formiggini took particular interest in including women in his dictionary, it is not a surprise to find among the talking postcards several renowned women like Sibilla Aleramo, Mercede Mundula, Ada Negri, or Emilia Santamaria, not only his beloved wife but also one of the most appreciated Italian pedagogists of the XX century.

Chi è? became popular in Italy and abroad and became one of the most appreciated among Formiggini’s books. It was widely reviewed in foreign newspapers and could be found in libraries of various countries. Several editions appear in the library of Casa Italiana at Columbia University, where Giuseppe Prezzolini referenced it in his academic courses on “Bibliography and Bibliographical method” in the 1940s.

The combination was such a success that the Cartoline can easily be found today in the private archives of writers and scholars, attesting to the wide circulation of Formiggini’s invention. The wide circulation of Chi è? and the Cartoline parlanti in Italy and abroad was part of the broader program for the dissemination of Italian books and culture worldwide that drove Formiggini’s entire life and publishing activity. His efforts in seeking new and original ways to advertise his publications were part of a well-structured commercial strategy to bring Italian culture to other countries, especially to the United States where Italian studies were flourishing, as demonstrated by the Casa Italiana at Columbia University with its rich library and the Italian Book Exhibition of 1928.

Formiggioni’s visionary project aimed at creating a “correspondence of affection and consensus among all educated foreigners” that would encourage international cultural and literary dialogue, together with sympathy and respect between all people. Formiggini’s vision was far from the imperialist impetus of Fascism and even farther from Giovanni Gentile’s policy of cultural supremacy. Their conflict caused a violent rupture between Formiggini and the government institutions. In spite of everything, until his last days, he remained convinced that a world could exist in which culture outdid politics, where ideas and books could circulate freely.

This article is loosely based on:

Elisa Pederzoli, “Who’s who(se) epitext?” The Cartoline parlanti of Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, «Interférences littéraires/Literaire interferenties», 23, «Seuils/Paratexts, trente ans après », ed. by Guido Mattia Gallerani, Maria Chiara Gnocchi, Donata Meneghelli, Paolo Tinti, May 2019.

A brief Bibliography

A.F. Formiggini editore 1878-1938. Mostra documentaria. Biblioteca Estense, Modena 7 febbraio-31 marzo 1980, S.T.E.M. Mucchi, Modena, 1980

Angelo Fortunato Formiggini: ridere, leggere e scrivere nell’Italia del primo Novecento, catalogo di mostra (Modena, Gallerie Estensi, 28 febbraio – 30 giugno 2019) a cura di Matteo Al Kalak, schede di Annalisa Battini, Elisa Pederzoli, Milena Ricci, Rosiana Schiuma, Modena: Artestampa, 2019

Angelo Fortunato Formiggini. Un editore del Novecento, a cura di Luigi Balsamo e Renzo Cremante, il Mulino, Bologna, 1981

Ugo Berti Arnoaldi, Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, in «Dizionario del fascismo», Einaudi, Torino, 2002

Antonio Castronuovo, Formíggini. Un editore piccino picciò, Stampa Alternativa, Viterbo, 2018

La cronaca della festa, 1908-2008. Omaggio ad Angelo Fortunato Formiggini un secolo dopo, a cura di Nicola Bonazzi, Margherita Bai, Margherita Marchiori, Artestampa, Modena, 2008

Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, La Ficozza filosofica del fascismo e la marcia sulla Leonardo. Libro edificante e sollazzevole, Formiggini, Roma, 1923

Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, “Manuale di propedeutica editoriale. Cedole librarie e cartoline parlanti”, in: L’Italia che scrive, 1929.

Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, Parole in libertà, a cura di Margherita Bai, Artestampa, Modena, 2009

Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, Trent’anni dopo. Storia della mia casa editrice, Levi, Vaciglio (MO), 1978

Emilio Mattioli, Alessandro Serra, Annali delle edizioni Formiggini 1908-1938, S.T.E.M. Mucchi, Modena, 1980

Giorgio Montecchi, Formiggini, Angelo Fortunato, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 49, Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana, Roma, 1997, p. 48-52

Olga Ragusa, “Prezzolini e la diffusione del libro italiano”, in: Cartevive, April 1997.

Dustin Illingsworth, “How author photos change the way we read. On making eye contact with iconic writers”, in: Literary Hub, October 27, 2015 (https://lithub.com/how- author-photos-change-the-way-we-read/).

Marie Jennequin, « Le “portrait” d’Auteur au Moyen Âge : parcours iconographique à travers les miniatures de quelques manuscrits », in Interférences littéraires, nouvelle série, « Iconographies de l’écrivain », 2009.

Giuseppina Zappella, Il ritratto librario, Manziana, Vecchiarelli, 2007.

The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, vol. IV, 1830-1914, edited by David MCKitterick Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Adriana Chemello, “La letteratura popolare di largo consumo”, in Storia dell’editoria nell’Italia contemporanea, a cura di Gabriele Turi, Firenze, Giunti, 1997.

Elisa Pederzoli, “L’Archivio delle recensioni di Angelo Fortunato Formiggini a Modena: il ‘Vieusseux del XX secolo’”, in: TECA. Rivista internazionale di arte e di storia della scrittura, del libro, della lettura, 2015.

Ernesto Milano, Angelo Fortunato Formiggini, Rimini, Luisé, 1987.

Elisa Pederzoli, “L’arte di farsi conoscere”. Formiggini e la diffusione del libro e della cultura italiana nel mondo, Roma, Associazione Italiana Biblioteche, 2019.

Vittorio Ponzani, Dalla filosofia del ridere alla promozione del libro: la Biblioteca circolante di A.F. Formiggini (Roma 1922-1938), presentazione di Alberto Petrucciani, Pistoia, Settegiorni, 2017.

Il sorriso al potere. I Classici del ridere di Angelo Fortunato Formiggini (1913-1938), a cura di Irene Piazzoni e Giuseppe Polimeni, Milano, Franco Angeli, 2020.

Gianfranco Tortorelli, “La letteratura straniera nelle pagine de L’Italia che scrive e I libri del giorno”, in Stampa e piccola editoria tra le due Guerre, a cura di Ada Gigli Marchetti e Luisa Finocchi, Milano, Franco Angeli, 1997.

Gianfranco Tortorelli, L’Italia che scrive, 1918-1938. L’editoria nell’esperienza di A.F. Formiggini, Milano, Franco Angeli, 1996.

Angelo Lipari, “Gossip and News from Italy”, in: The Modern Language Journal, December 1927