Curiosities of Literature

Original article. Isaac was born in Enfield, Middlesex, England, the only child of Benjamin D’Israeli (1730–1816), a Jewish merchant who had emigrated from Cento, Italy in 1748, and his second wife, Sarah Syprut de Gabay Villa Real (1742/3–1825). Isaac received much of his education in Leiden. At the age of 16, he began his literary career with some verses addressed to Samuel Johnson. He became a frequent guest at the table of the publisher John Murray and became one of the noted bibliophiles of the time.

On 10 February 1802, D’Israeli married Maria Basevi (1774/5–1847), who came from another London merchant family of Italian-Jewish extraction. The marriage was a happy one, producing five children: Sarah (“Sa”; 1802–1859); Benjamin (“Ben” or “Dizzy”; 1804–1881); Naphtali (b. 1807, died in infancy); Raphael (“Ralph”; 1809–1898); and Jacobus (“James” or “Jem”; 1813–1868). T

He penned a handful of English adaptations of traditional tales from the Middle East, wrote a few historical biographies, and published a number of poems. His most popular work was a collection of essays entitled Curiosities of Literature. The work contained myriad anecdotes about historical persons and events, unusual books, and the habits of book-collectors.

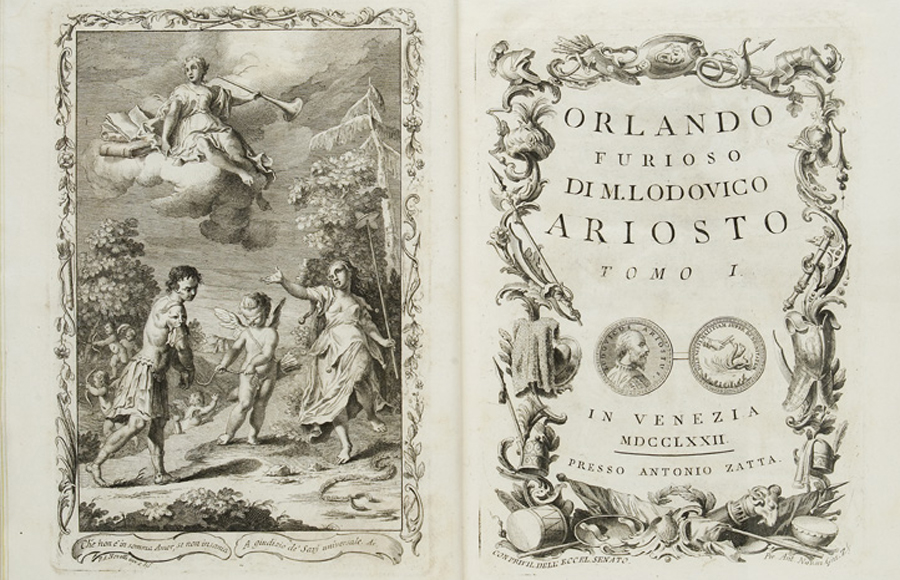

It surprises one to find among the literary Italians the merits of Ariosto most keenly disputed: slaves to classical authority, they bend down to the majestic regularity of Tasso. Yet the father of Tasso, before his son had rivalled the romantic Ariosto, describes in a letter the effects of the “Orlando” on the people:—“There is no man of learning, no mechanic, no lad, no girl, no old man, who are satisfied to read the ‘Orlando Furioso’ once. This poem serves as the solace of the traveller, who fatigued on his journey deceives his lassitude by chanting some octaves of this poem. You may hear them sing these stanzas in the streets and in the fields every day.” One would have expected that Ariosto would have been the favourite of the people, and Tasso of the critics. But in Venice the gondoliers, and others, sing passages which are generally taken from Tasso, and rarely from Ariosto. A different fate, I imagined, would have attended the poet who has been distinguished by the epithet of “The Divine.” I have been told by an Italian man of letters, that this circumstance arose from the relation which Tasso’s poem bears to Turkish affairs; as many of the common people have passed into Turkey, either by chance or by war. Besides the long antipathy existing between the Venetians and the Turks gave additional force to the patriotic poetry of Tasso. We cannot boast of any similar poems. Thus it was that the people of Greece and lonia sang the poems of Homer.

The Academia della Crusca gave a public preference to Ariosto. This irritated certain critics, and none more than Chapelain, who could taste the regularity of Tasso, but not feel the “brave disorder” of Ariosto. He could not approve of those writers,

“Who snatch a grace beyond the reach of art.”

“I thank you,” he writes, “for the sonnet which your indignation dictated, at the Academy’s preference of Ariosto to Tasso. This judgment is overthrown by the confessions of many of the Cruscanti, my associates. It would be tedious to enter into its discussion; but it was passion and not equity that prompted that decision. We confess, that as to what concerns invention and purity of language, Ariosto has eminently the advantage over Tasso; but majesty, pomp, numbers, and a style truly sublime, united to regularity of design, raise the latter so much above the other, that no comparison can fairly exist.”

What Chapelain says is perhaps just; though I did not know that Ariosto’s language was purer than Tasso’s.

Dr. Cocchi, the great Italian critic, compared “Ariosto’s poem to the richer kind of harlequin’s habit, made up of pieces of the very best silk, and of the liveliest colours. The parts of it are many of them more beautiful than in Tasso’s poem, but the whole in Tasso is without comparison more of a piece and better made.” The critic was extricating himself as safely as he could out of this critical dilemma; for the disputes were then so violent, that I think one of the disputants took to his bed, and was said to have died of Ariosto and Tasso.

It is the conceit of an Italian to give the name of April to Ariosto, because it is the season of flowers; and that of September to Tasso, which is that of fruits. Tiraboschi judiciously observes that no comparison ought to be made between these great rivals. It is comparing Ovid’s “Metamorphoses” with Virgil’s “Æneid;” they are quite different things. In his characters of the two poets, he distinguishes between a romantic poem and a regular epic. Their designs required distinct perfections. But an English reader is not enabled by the wretched versions of Hoole to echo the verse of La Fontaine, “JE CHERIS L’Arioste et J’ESTIME Le Tasse.”

Boileau, some time before his death, was asked by a critic if he had repented of his celebrated decision concerning the merits of Tasso, whom some Italians had compared with those of Virgil; this had awakened the vengeance of Boileau, who hurled his bolts at the violators of classical majesty. It is supposed that he was ignorant of the Italian language, but by some expressions in his following answer, we may be led to think that Boileau was not ignorant of Italian.

“I have so little changed my opinion, that on a re-perusal lately of Tasso, I was sorry that I had not more amply explained myself on this subject in some of my reflections on ‘Longinus.” I should have begun by acknowledging that Tasso had a sublime genius, of great compass, with happy dispositions for the higher poetry. But when I came to the use he made of his talents, I should have shown that judicious discernment rarely prevailed in his works. That in the greater part of his narrations he attached himself to the agreeable oftener than to the just. That his descriptions are almost always overcharged with superfluous ornaments. That in painting the strongest passions, and in the midst of the agitations they excite, frequently he degenerates into witticisms, which abruptly destroy the pathetic. That he abounds with images of too florid a kind; affected turns; conceits and frivolous thoughts; which, far from being adapted to his Jerusalem, could hardly be supportable in his ‘Aminta.’ So that all this, opposed to the gravity, the sobriety, the majesty of Virgil, what is it but tinsel compared with gold?”

It must be acknowledged that this passage, which is to be found in the “Histoire de l’Académie,” t. ii, p. 276, may serve as an excellent commentary on our poet’s well-known censure. The merits of Tasso are exactly discriminated; and this particular criticism must be valuable to the lovers of poetry. The errors of Tasso were, however, national.

An anonymous gentleman has greatly obliged me with an account of the recitation of these two poets by the gondoliers of Venice, extracted from his travelling pocket-book.