Books Within Books: Mauro Perani, passionate archeologist of the written word.

Alessandro CassinOne sensational discovery – in our media driven world – can spread the excitement from the academic and scientific world to the general public. In 2013, professor Mauro Perani’s discovery of the oldest complete Torah scroll, containing the full texts of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy handwritten between 1155 and 1225 C.E, is such an event. And another case of hiding in plain sight: the sheepskin document, conserved in the University of Bologna Library, had been erroneously catalogued over a century ago by Leonello Modona as a 17th century manuscript. Perani was not persuaded. During his ongoing research on Hebrew manuscripts in the library, through a series of discoveries, he gradually came to the conclusion that the nearly 120-foot-long scroll was significantly older. A detailed paleographic analysis was followed by carbon-14 tests at the University of Salento and later at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, confirming his 12th-13th century attribution. The Bologna Sefer Torah scroll, poetically described by Perani as fossil, a literary fossil of a lost calligraphic and ornamental tradition, instantly become a “media darling”. Sotheby’s offered to auction it at an undisclosed record price, international institutions are anticipating if and when it will be possible to borrow and exhibit it, and which imaging techniques might be best to render it accessible to the public.

“The Sefer Torah is certainly a major discovery” points out Mauro Perani “but should be seen as the tip of the iceberg, there is much work ahead”.

Following the pioneering work of the late Giuseppe Baruch Sermoneta, who launched the Hebrew Fragments in Italy Project in 1981, Professor Perani (University of Bologna) is today the main force behind a collective effort to study and catalog the 8,000 fragments of Hebrew manuscripts collected in the so-called “Italian and European Genizah Project”.

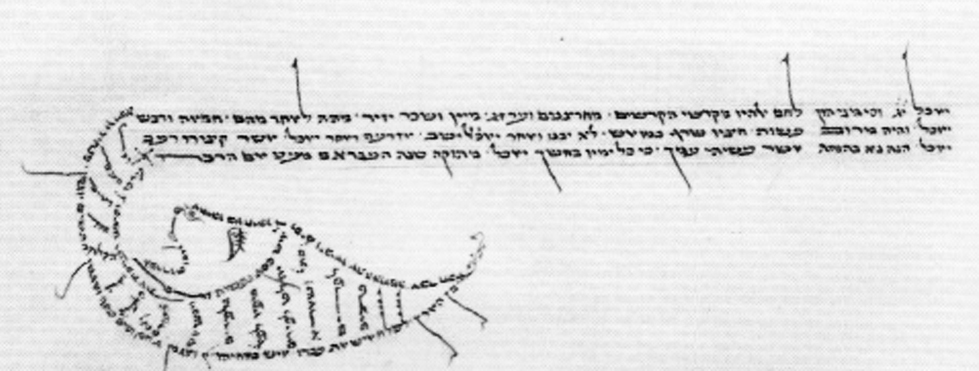

The Italian scholar was recently in New York for a series of conferences that included a talk on April 3rd, sponsored by the Institute for Israeli and Jewish Studies of Columbia University. The focus of his talk was the discovery and significance of these medieval Hebrew manuscript fragments, often reused in later times to bind books and registers in libraries, mostly in Italy and Spain. “The term Genizah” he explained to a rapt audience “is somewhat misleading: a true Genizah preserves sacred texts from profanation, while this is the result of the recycling of used parchment”. A term he prefers is “Book within Books”, yet even this does not cover the whole phenomenon, as Perani, in his quasi detective work, has also identified manuscript fragments used for patching inside musical instruments such as viola da gambas and violins…

“The production of manuscripts came to a end around 1530, as texts became available as printed books at a price 100 to 200 time cheaper than in manuscript form”. The surviving parchment documents uncovered up to date represent only an estimated 5% of the Hebrew manuscripts produced during the Midle Ages. “The majority of manuscripts did not survive for diametrical opposing reasons: either damage caused by repeated readings and study, as well as travel and inclement weather, or of course from Christian confiscation and destruction attempts”. While recycling parchment documents as binding material did not pertain only to Hebrew manuscripts, but also to Latin, Greek and Italian ones, scientific and musical texts, in this case these findings sheds light on both the religious practices and every day lives of the Jews in Italy. Perani was able to graph a peak in the recycling of Talmud pages as binding material in the years immediately following Pope Julius II ban of the Talmud in 1553. While the paper pages of the Talmud were often burned, the parchment was sold and reused.

Recent findings in Girona, Spain, illustrate a major difference in the recycling practices between Spain and Italy. In Spain paper documents were recycled as bindings by gluing many pages together, (making the ungluing today particularly arduous), whereas in Italy paper was rarely used for binding.

As historians have documented, between the XIV and XV century, Jews from various European countries, often fleeing persecution, settled in the central and northern regions of the Italian peninsula. These migrants often traveled with very few possessions, yet carried with them their precious books in manuscript form. This accounts for Italy having the highest concentration of Hebrew texts of different provenances. In addition, once in Italy, the texts were often copied by local scribes or by foreign soferim who continued to use their own traditions, which in turn explains why today most of the Hebrew manuscript conserved in libraries throughout the world have an Italian origin.

Professor Perani is convinced that there are significant numbers of fragments still to be discovered, and numbers indicate without a doubt that Italy is the place to look for them. As of today 6000 thousand Medieval Hebrew fragments were discovered in Italy versus 1700 in the rest of Europe: about 700 in Germany, 500 in Austria, 170 in Hungary and about 150 in Spain.

The continuous findings of the “Italian and European Genizah Project” constitute a treasure trove both for textual analysis and historical extrapolation. The discovered fragments include important texts by Joseph ben Shimon Kara, a contemporary of Rashi, and fragments relating to 160 manuscripts from the Talmud bavli and Yerushalmi, otherwise lost.

This exciting and open ended project deserves wider international support as its cultural horizon radiates in various directions, well beyond the field of Jewish Studies: from the history of books to Christian, Muslim and Jewish cultural exchanges.