Some Observations on Catholicism, Fascism and Totalitarianism During the Papacy of Pius XI.

On David L. Kertzer’s The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe (New York: Random House, 2014).

Gentile is a professor at the Sapienza University of Rome. He considers fascism a form of political religion. He also applied the theory of political religion to the United States after the September 11 attacks.

Emilio Gentile, an internationally renowned authority on fascism and totalitarianism, argues that politics over the past two centuries has often taken on the features of religion, claiming as its own the prerogative of defining the fundamental purpose and meaning of human life. Secular political entities such as the nation, the state, race, class, and the party became the focus of myths, rituals, and commandments and gradually became objects of faith, loyalty, and reverence.

Among his books are:

Storia del partito fascista. 1919-1922. Movimento e milizia. 1989

The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy, 1996, Harvard University Press

Politics as Religion. Princeton University Press. 2006.

La Grande Italia: The Myth of the Nation in the Twentieth Century. University of Wisconsin Press. 2009.

God’s Democracy: American Religion After September 11. Greenwood Press. 2008.

Né stato né nazione. Italiani senza meta, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 2010

Translation by Steve Baker

It was on November 4, 1921 that the archbishop of Milan, Achille Ratti, first met Benito Mussolini. The occasion was a religious ceremony held in the Duomo of Milan to commemorate the fallen heroes of the Great War. The archbishop permitted the fascists to enter the church with their pennants, and Mussolini greatly appreciated the prelate’s accommodation. There does not seem to have been any other meeting, not even a chance encounter, between Cardinal Ratti and the leader of the black shirts, whose headquarters were in Milan. There is no proof to support the piece of information reported by Margherita Sarfatti (and repeated by other Mussolini biographers) of a meeting in the same Duomo during the memorial services for the victims of an attack at the “Diana” theater in March 1921. Indeed, at that time, Ratti was serving as apostolic nuncio in Poland. He only returned to Rome on June 4, 1921, and it was not until the thirteenth of that month that he was elected archbishop of Milan.[1]

When he allowed the fascists to participate in his religious function with their pennants, the archbishop was certainly not naive to the fact that Mussolini, a socialist, had served as a propagandist for atheism. Not only was he was fiercely anticlerical, but he had also proclaimed himself to be an anti-Christian pagan, who remained as such when he converted to interventionist nationalism in 1914 and in 1919 when he started the fascist movement. But he also knew that in 1921 Mussolini had already long abandoned atheism, anticlericalism and anti-Christianity, and that he had often exalted the Church in Rome,[2] in print and in his speeches. In his first parliamentary speech, given on June 21, 1921, Mussolini declared that fascism “neither preaches, nor practices anticlericalism.” He did not condone divorce and recognized in the Roman Church the lineage of the imperial Latin tradition: “It is my conviction that the only universal idea in Rome is that which radiates from the Vatican.” For this reason, the fascist leader said “that, if the Vatican definitively renounces its temporal dreams – and I think that it is already on this road –, Italy, profane or secular, should provide the Vatican with material assistance, the kind of economic support for schools, churches, hospitals or other public works that a secular government can muster. Because the development of Catholicism in the world, the addition of four hundred million people who are watching Rome from all corners of the globe, is of interest and a point of pride even for us Italians.”[3]

Such declarations were not “Mussolini’s surprising embrace of the Church,” nor did the Duce mean to say that fascism “would build a Catholic state befitting a Catholic nation,” as David L.Kertzer states.[4] In fact, a year had already passed since May 1920, at the third national congress of the fascist movement, where Mussolini had changed his anticlerical, anti-Christian and anti-Catholic attitudes, driven by purely political motives, stating that “the Vatican represents four hundred million people spread throughout the world and an intelligent politician should use this colossal force to his own expansionist ends.”[5]

In the months leading up to fascism’s ascent to power, Mussolini accentuated his respectful declarations regarding the Church, referring only to its “spiritual power” that should be utilized in order to bolster the political power of the Italian nation.[6] On January 24, 1922, commenting on the death of Benedict XV, Mussolini wrote: “In this hour, people of all races and from all continents are looking to Rome. This fact denotes a certain grandiosity that cannot be diminished by the pronouncements or the silence of the secular world, which has not created and will never create anything that rises up, even in part, to the enormous spiritual power of Catholicism.”The emotions generated by the death of the pope in the civil world are the proof “that there is a powerful resurgence of the religious elements of life in the human soul. Scientific secularism and its logical degeneration, represented by charlatan anti-clericalism, are in decline. People have always cultivated and will continue to cultivate a feeling and a hope for the afterlife. The vast anonymous masses will forever be tormented by a desire to escape from this brief life on earth and from its many miseries to seek refuge in the absolute of faith.” Touching on the relations between Church and State in Italy, Mussolini noted that the new Italian generations had “a different appreciation of all the spiritual elements of life, including Catholicism, which is the Latin religion par excellence, thus also of the papacy, which is the heart and soul of this religion.”For this reason, he added, he hoped to expand the relationship between State and Church, “which we have supported for quite some time in this column and elsewhere.” Mussolini, nevertheless, declared it was foolish “to expect to turn it into a national Church in service of the nation”: “The power, the prestige, the millenary and enduring appeal of Catholicism depend precisely on the fact that Catholicism is not the religion of a given nation or of a given race, but it is the religion of all nations and all races. The force of Catholicism – as the word itself suggests – lies in its universalism. As a result, Rome is the only city in the world that can call itself ‘universal.’”[7]

Cardinal Ratti certainlyread Mussolini’s article in “Il Popolo d’Italia,” which was published in Milan. We know it was precisely in this period that the cardinal came out in favor of the fascist leader. In a private interview in 1937, he revealed to a French journalist: “Mussolini is a remarkable man: do you understand? Remarkable.” Then, the journalist reports, the cardinal added, “taking on a prophetic tone”: “He is a man who advances in great strides and conquers everything like a force of nature. He is a neo-convert, because he comes from the ranks of the extreme left, and, like a novice, he is possessed by a zeal that drives him forward. He snatches up his followers from their school desks and, at once, he elevates them to the dignity of men, armed men. He seduces them, turns them into fanatics, rules over their imaginations. Do you realize what this means, what kind of power he possesses? … He is the future. It remains to be seen how it will end up and what he will do with his power. How will he align himself when it comes time to chose an alliance? Will he be able to resist the temptation – that plagues all leaders – of assuming the role of absolute dictator?”Then the cardinal observed, “articulating his views very clearly,” that it was not good that “one individual should become omnipotent. Glory is insidious, flesh is weak, and man is limited.” Then, after a pause of silence, he added: “What does genius consist of anyway? It consists of at least a modicum of folly. And woe be to the mustard seed if it grows into a tree too quickly…”[8]

What Mussolini thought of cardinal Ratti we know from his comment regarding the election of Pius XI. On February 6, 1922, when the new pope wanted to bless the crowd in St. Peter’s Square – something the pope had not done since 1870 –, Mussolini attended the ceremony and said that the new pope possessed religious and human qualities that endeared him even to the secular world. Beyond being “a man of great historical, political and philosophical learning,” animated by the “liveliest sense of Italianity,” “like those who live or have lived outside the borders of the Homeland”: “I maintain – concluded Mussolini – that with Pius XI relations between Italy and the Vatican will improve.”[9]

In reconstructing relations between Pius XI and Mussolini, it is important to remember these initial accounts, which Kertzer’s book, nevertheless, does not mention, because they are necessary in order to understand the premises that gave rise to the long relationship between the head of the Church and the head of the fascist regime, which Kertzer recounts on the basis of unpublished documentation from the fascist archives and the Secret Vatican Archive. Kertzer sheds light on certain unknown or little known aspects of the Holy See, and on the agreements between the Vatican and the fascist regime during the preparation of the anti-Semitic laws. Nevertheless, as we will see, the book entirely neglects or only hints at certain questions, like totalitarianism and the “fascist religion,” which are essential in order to understand the motives for which an agreement that seemed solid and based on mutual interests of the two protagonists and of the two institutions. Over the years, their pact was increasingly imperiled by tensions, differences in opinion and public clashes, until they reached a clamorous breaking point, avoided only due to the death of Pious XI, a “convenient death,” as Kertzer efficaciously defines it.

The “secret history” of the relationship between Pius XI and Mussolini recounted by Kertzer is particularly effective when it sheds light on the personalities of Pius XI and Mussolini and what they had in common. “For all their obvious differences, the pope and Mussolini were alike in many ways. Both could have no real friends, for friendship implied equality. Both insisted on being obeyed, and those around them quaked at the thought of saying anything that would displease them. They made an odd couple, but the pope had quickly come to recognize the benefits of casting his lot with the former priest-eater.”[10] Both were authoritarian, intolerant, intransigent, and inflexible in demanding obedience and in denying dissent. Precisely for these shared traits, the pope and Mussolini clashed on issues that each deemed essential from their point of view, as happened during the Concordat negotiations, the conflict over Catholic Action in 1931 and the adoption of the racial and anti-Semitic laws on the part of the fascist regime in 1938. Even if Kertzer insists that there was a willingness to reach a compromise in order to avoid irreparably damaging their relations, as occurred after the episodes just cited, it should, nevertheless, be clarified that such willingness ceased in the moment when both men held that a compromise would have meant a grave offense to their respective personal authority and a renunciation of what they held to be their supreme mission: for the pope, the confirmation of the absolute primacy of the Church; for the Duce, the confirmation of the absolute primacy of the fascist State

Despite the divergence of their goals, it is certain that the “secret history” of the relationship of Pius XI with Mussolini, during the seventeen years of his papacy, was based on certain ideas they held in common: “Despite all their differences – Kertzer accurately observes –, the two men shared some important values. Neither had any sympathy for parliamentary democracy. Neither believed in freedom of speech or freedom of association. Both saw Communism as a grave threat. Both thought Italy was mired in crisis and that the current political system was beyond salvation.”[11]

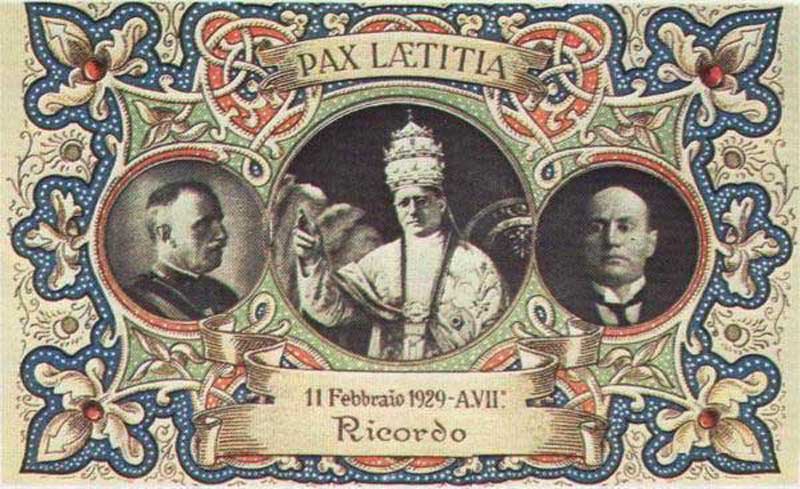

These were the premises on which, after the march on Rome, the agreement was born between Mussolini and Pius XI – ratified with the signing of the Lateran Pacts in 1929 – that legitimated the fascist regime in the eyes of the Catholic reactionaries, conservatives and traditionalists, but not of the Catholic anti-fascists, such as the founder of the Partito Popolare, Don Luigi Sturzo and other Italian Catholic intellectuals and politicians, liberal and democratic, who were forced to remain silent or sent into exile. The search for an agreement with the Church does not mean that, in my opinion, Mussolini wanted “to build a Catholic state befitting a Catholic nation,” as Kertzer claims. Much less do I think that Mussolini “did all he could to identify the Italian state with the Catholic Church.”[12] The Duce only ever wanted to avail himself of the Church as a means of consolidating the fascist State and to involve Catholicism in his imperial project, as Pius XI himself dramatically came to realize at the end of the 1930s. The Duce’s strategy intended rather, I would say, to identify the Catholic Church with the Fascist State.Furthermore, it seems that this is the overall interpretation that Kertzer presents of the meaning and goal that Pius XI and the Duce attributed to their relationship: “The pope was eager to use the Fascists’ power to resurrect a Catholic state, although was not so foolish as to think he could ever ‘Christianize’ Mussolini. The Duce was eager to use the power of the Church to solidify his own rule, but in his view the Catholic clergy were to be the handmaidens of the Fascist government, a tool to ensure popular support for the regime.”[13]

Drawing on unpublished documents from the fascist archives, Kertzer brought to light embarrassing vicissitudes inside the Vatican, like the pederasty that, according to police informants, was practiced within the wall of the Holy See by Monsignor Camillo Caccia Dominioni, who was nominated in 1921 by Benedict XV to serve as the pope’s “maestro di Camera” and confirmed by Pius XI, who always had him at his side and nominated him cardinal in 1935.[14]Documents from the Vatican archives show just how wide-spread and deep-rooted anti-Semitism was among the Catholic hierarchy and in particular among the Jesuits, like Father Pietro Tacchi Venturi, the primary mediator in the relations between Pius XI and Mussolini, who saw in the Jews the principal conspirators in a worldwide plot against the Catholic Church together with the Masons and the Bolsheviks.[15]Kertzer demonstrates that, in the period of the anti-Semitic laws, which effected even those Jews who had converted to Catholicism and married in Catholic ceremonies, Tacchi Venturi was the author of an agreement between the Church and the regime, with which he offered up the silence of the Church regarding the anti-Semitic laws in exchange for safeguarding Catholic Action.[16] Nevertheless, despite this agreement, Kertzer writes, Pius XI “viewed the new racial laws as part of a larger, troubling pattern. Mussolini, rather than working with the Vatican to bring about a confessional state in which Catholicism infused Fascism with its values, seemed bent on creating a separate Fascist religion.”[17]

Over the course of his narration, Kertzer only occasionally hints, as in this case, at the problem of “a central Fascist religion.” On another occasion, he states “the Catholic clergy played a crucial role in lending the Duce cult a religious flavor, promoting a heady mix of Fascist and Catholic rituals.”[18] In the end, in a note, he writes: “A number of historians maintain that Mussolini was constructing a civil religion in Italy. The Fascists themselves used that term.”[19] In the absence of explicit references to those historians who “maintain that Mussolini was constructing a civil religion in Italy,” it is difficult to understand what these historians meant by this statement. What can be stated with certainty is that Mussolini did not ever attempt to “construct a civil religion,” even if he did not stop other fascists from talking about fascism as a political religion. In the Dottrina del fascismo published in 1932, the Duce officially proclaimed, that fascism did not intend to imitate the French Revolution by placing a new god on the nation’s altar, but he recognized that “the God of ascetics, of saints, and of heroes, and also God which is seen and worshippedby the primitive and genuine heart of the people.”[20] Two years prior, in a secret speech he gave to the upper echelon of the fascist party, the Duce had ordered his followers not to assume anti-religious attitudes toward the clergy and Catholic Action: “A fight on this ground between Church and State, the State would lose. Catholic Action is another matter. There confrontation is a duty. When it comes to religion, maximum respect – which Fascism has always given. … A Holy War in Italy? Never!”[21] And again in 1934, to the French newspaper “Le Figaro,” Mussolini declared: “It never even remotely entered our head to found a new religion of the State, or to subject the religion professed by all Italians to the State.”[22]

Beyond the declarations of the Duce and other fascists, the question of “Fascist religion,” in a history of the relationship between Catholic Church and the fascist regime, between Pius XI and Mussolini, is an extremely important historical problem, one of great import, and of increasing importance to Pius XI and many others in the Church, like Monsignor Domenico Tardini. They came to realize, as time passed, that fascist totalitarianism was itself a new pagan religion that utilized Catholicism to further its political goals, while preaching anti-Christian ethics and practicing a politics of integration that intended to dominate not only individuals but also their consciences.

Given that it is more narrative than analytical in nature, Kertzer’s book barely touches on the question of fascist religion and totalitarianism in a couple of episodes, while it would have merited more in-depth attention, especially on the basis of this new documentation, since it was crucial in the relations between Pius XI and fascism, as the studies that have been published on this subject over the last decade have showed.[23]

Historiographers have for a long time placed at the center of their interpretation of the relations between the Church and the fascist regime the attitude of the Church toward totalitarianism, understood as a system of political domination based on a single party and on the regimentation of the indoctrinated masses beneath an exclusive ideology, which the Catholics themselves interpreted and condemned as a “political religion,” incompatible with the Catholic faith. Scholars of the Catholic Church in the 1930s and 40s had already addressed this problem. Even if at the time they could only avail themselves of sources that had already been made public, the most acute scholars understood the fundamental questions, on the basis of which the agreement between the Church and the fascist regime was based. Above all, they understood the motivations behind the source of recurring tension, contrast and conflict. They often anticipated the conclusions drawn by the most recent studies. In 1934, Georges Seldes distinguished, in the relations between Church and fascism, four moments: “reciprocal distrust and Fascist hostility; reconciliation (the Lateran agreement); open warfare [the conflict over Catholic Action in 1931]; the apparent peace which continues today.”[24] Seldes spoke of “apparent peace” but knew that it rested on unstable foundations, because it was a peace that was more like a truce than a definitive removal of every reason for conflict: “the causes for disagreement between Church and state are much more numerous than the reasons for agreement. The most important lies in the profound, essential and irreducible opposition which exists between the spirit and philosophy of Fascism and Catholic doctrine, or, indeed, Christian doctrine.”[25]

Three years later, even if no new disagreement had disturbed “the apparent peace” between the Church and the fascist regime, which had instead garnered the broadest and most enthusiastic public support from the vast majority of the clergy and the highest ranking officials of the Church (though not Pius XI personally) for the war in Ethiopia, other scholars of the Catholic Church observed that new shadows were being cast over relations between the Pope and the fascist regime. In 1937, in one of the first biographies of Pius XI, William Teeling, an Irish Catholic, whose family had played an important role in the Vatican, observed that the Duce’s behavior as “protector of Islam” during his trip to Libya in March of that year, was for the pope a great disappointment. It destroyed Pius XI’s hope that the Church, after having supported fascist colonial conquest, would have been given free reign “to develop in Abyssinia and elsewhere in the Italian Empire.”[26] And the same scholar observed how Pius XI’s and the Vatican’s position became more and more unsustainable with respect to Catholics living under democratic regimes, who were hostile towards the fascist State considering it anti-Catholic and anti-Christian, as they watched “Pope Pius become more and more friendly with the leader of this Totalitarian State,” and so for this reason, from that time on, the non-Italian Catholic world held “that the Catholic Church cannot go on indefinitely having an Italian Pope and a majority of Italian Cardinals.”[27] Teeling echoed in his conclusive evaluation of Pius XI’s papacy the criticisms that quickly spread through the Catholic communities in democratic countries:

“There is no possibility, they think, of compromise between a totalitarianism that in the long run practically denies the authority of God and Christianity, in dealing with human beings, and they have a grave mistrust of the fact that so many elderly men, most of them over sixty years of age, should be guiding their activities from the very centre of this totalitarianism. Moreover, they feel that these elderly men are themselves of the same flesh and blood, and the same race, and from the same districts of those Fascists who are spreading this totalitarianism throughout the world, for at least eighty per cent of the authorities at the Vatican are Italian. They argue that for the moment many of these Italians are probably antifascist, since they were educated and already in power before the advent of Fascism; but they point to the fact that no Italian Bishop can now be appointed who is not favorable to Mussolini, and that no leader of the youth groups of Catholic Action in Italy can be appointed unless he is a Fascist. […]

“Such is the problem which has developed in the last fifteen years, during the Pontificate of Pope Pius. He has to face the rise of totalitarianism, and he has not yet been able to curb it in any noticeable degree. He began his reign with the hope that it would be one of peace, and it has turned out a tragedy in that he has found himself forced, against his will, to attack rather than to live in peace.

“He has shown himself, perhaps, a hard man, and a man who is hard to himself as to everybody else. At the age of eighty, tortured by illness, he works long into the night. One cannot but wonder if in these modern days it would not be best if a Pope retired at a certain age limit.

“It is surely a tragedy that the teaching of Catholicism should seem to be combined with a background of a political national doctrine, which only a very small percentage of the Catholic World believes in any sense a permanent political doctrine, namely Fascism.”[28]

Teeling writes in 1937.

Pius XI was a voracious reader and it seemed unlikely that he had not read this biography, which was reprinted three times in three years, and was written by a Catholic who dedicated it “to the Catholics who have faith in the future of democracy.” I imagine that he read it and that reading it contributed to reinforcing the idea, which had become ever more agonizing in the last few months of his life, that fascist totalitarianism was not reconcilable with Catholic “totalitarianism.” “What made the past months so painful to the pope – Kertzer observed on the matter – was his realization that his dreams of turning Italy into a confessional state – one where the machinery of the authoritarian regime would be at the service of Church – had been so naïve.”[29] His comment seems appropriate from the psychological point of view, but from the purely historical perspective, it would have been opportune to research and reflect further into the motivations of the tormented individual, as well as to study more attentively Pius XI’s attitude towards the phenomenon of totalitarianism and of the sacralization of politics, because this phenomenon disturbed the pope from the beginning of the fascist regime. And it never left him, despite his “naive” hope of Christianizing fascism. As early as 1926, Pius XI had considered writing an encyclical condemning nationalism as a secular religion.[30]And already in 1935, he had ordered the Holy Office to prepare an Elenchus Propositionum de Nationalismo, Stirpis cultu, Totalismothat was reworked over the next few years and that served as preparatory material for the encyclical against National-Socialism.[31] It anticipated his last encyclical Humani generis unitas, which his successor Pius XII decided to bury in the archives.[32]

We do not know how the relations between the Church and the fascist regime would have evolved had Pius XI not “conveniently died.” Let us imagine, however, that Pius XI read Teeling’s book and that the passages cited above aggravated his personal torment, perhaps immediately after he had been consoled by the thought that “regimes come and go, but the Church eternally remains.” Those passages would have shown him that, at the end of his life, he had failed his mission, because he had believed that the “remarkable Mussolini” was a man who had been sent by Providence to bring Italy back to the Church. And instead he had cast onto the Church the dismal shadow of totalitarianism.

Footnotes

[1] Margherita Sarfatti, Dux, Mondadori, Milano 1926, p. 241.

[2] See Emilio Gentile, Contro Cesare. Cristianesimo e totalitarismo nell’epoca dei fascismi, Feltrinelli Milano 2010, pp. 81 ff.

[3] Benito Mussolini, Opera omnia, eds. Edoardo and Duilio Susmel, 35 vols., Firenze 1951-1963, vol. XVI, pp. 443-44.

[4] David L. Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe, New York, Random House, 2014, p. 27.

[5] Mussolini, Opera omnia, vol. XIV, p. 471.

[6] Gentile, Contro Cesare, pp. 88-94.

[7] Mussolini, Opera omnia, vol. XVIII, pp. 16-18.

[8] Luc Valti, «Celui qui ouvrit le Vatican», L’Illustration, 9 janvier 1937, p. 33.

[9] Cited in Giulio Castelli, La Chiesa e il fascismo, Roma, L’Arnia, 1951, pp. 45-46.

[10] Kertzer, The pope and Mussolini, p. 68.

[11] Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini, p. 48.

[12] Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini, p. 100.

[13] Ivi, pp. 120-121.

[14] Kertzer, The pope and Mussolini, pp. ???.

[15] Ivi, pp. 88 ff.

[16] Ivi, pp. 299 ff.

[17] Ivi, pp. 324-325.

[18] Ivi, p. 174.

[19] Ivi, p. 434 n. 24.

[20] Cit. in Emilio Gentile, The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1996, p. 69.

[21] Ivi, p. 70.

[22] Ivi, p. 70.

[23] See Gentile, The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy, pp. 69-75; Id., Politics as Religion, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2006, pp. 89-97; Id. “New Idols: Catholicism in the face of Fascist totalitarianism,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 11, 2, June 2006, pp. 143-170; Id., Contro Cesare, passim;

[24] George Seldes, The Vatican: Yesterday – Today – Tomorrow, New York-London, Harper & Brothers, 1934, p. 372.

[25] Ivi, p. 372.

[26] William Teeling, The Pope in Politics: The Life and Work of Pope Pius XI, London, Lovat Dickinson, 1937, p. 134-135.

[27] Ivi, pp. 1-3.

[28] Ivi, pp. 281-283.[29] Kertzer, The pope and Mussolini, p. 355.

[30] See Gentile, Contro Cesare, pp. 174 ff.

[31] Peter Godman, Hitler and the Vatican: Inside the Secret Archives that Reveal the New Story of the Nazis and the Church, New York, Free Press, 2004.

[32] Georges Passelecq and Bernard Suchecky, The Hidden Encyclical of Pius XI, New York, Harcourt Brace, 1997.