The structure of History, a Novel, departs substantially from Morante’s previous novels and poses some interesting interpretative questions. While critics have often pointed to similarities with the narrative structure of 19th-century novels, perhaps one can look further back in time. I am thinking specifically of Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of The Plague Year, first published in 1722.

By 1974 Morante was an original and self-assured author, who had shown the ability to create innovative book structures (for example, Il Mondo Salvato dai Ragazzini) and was in no way derivative in her choices. Yet, despite critical stylistic differences, I am struck by the affinities between History, a Novel, and A Journal of The Plague Year.

Fact and fiction

Morante prefaces each of her chapters, with quasi-journalistic accounts of world events. The prefaces consist of factual information tinged by her own anarchist and ecological slant. The action of each chapter, except the first and the last, takes place each over a one year span, from 1941 to 1947, in Rome. Within the framework of the historical events that took place in Rome in that year, Morante constructs a spiraling sequence of fictional characters who engage in a variety of liaisons, adventures and entanglements.

Defoe places his action in London during the year 1665 when the city had been devastated by the plague. The novel reports and is primarily based on documents, medical treaties, burial records, and the such. Against a background of suffering, fear, and death, the author creates a cast of characters who inhabit the city and go through terrors of different kinds. Like in Morante’s novel, here too, next to darkness and unspeakable pain, we find episodes of solidarity, courage, and self- sacrifice, particularly among the humble.

Both authors render raw historical facts as integral components of their literary creations.

The narrator

The semi-omniscient narrator of Morante’s novel is a woman. At a few pivotal moments, she speaks in the first person, as someone who has witnessed the events being narrated and is personally acquainted with the characters. This narrative device confers credibility.

One can assume this is Morante’s own voice, as she resided on and off in Rome during those years.

During the plague in London of 1665, Daniel Defoe was only five years old. One can assume he had some personal memories, but more importantly, had heard many tales and reports. His narrator H.F., a saddler by profession, was an adult in 1665, thus credible as a witness.

While all the major characters in History, A Novel die, the narrator survives. Similarly, H.F. in A Journal of The Plague Year, observes an epidemic “that swept a hundred thousand souls away” and survives.

Mediated and somewhat disguised, the narrators of both novels are stand-ins for their authors.

The cityscape

History, a Novel takes place, in Rome, specifically in a few locations, described in photographic detail: San Lorenzo, Pietralata, the Tiburtina train station, the former Jewish Ghetto, and Testaccio. The author knew firsthand and researched each and every place in the novel.

H.F. In the Journal takes the reader around 1665 London. The novel names and describes, again in photographic detail, a multitude of streets, alleys, squares, churches, buildings, and taverns, that had since changed name and aspect.

Despite modernization and real-estate developments, readers of the two novels could walk around London and Rome and identify most of the locations.

Non-linear plots

After being introduced, Morante’s characters often disappear, only to reappear multiple times further down in the narration. Digressions abound, stories begin at one point and finish much later.

Defoe’s narrator wonders about town, his and our attention is captivated by characters and events, only to be interrupted by something, and then again, by something else.

Movement

The movement of the action in the two novels follow respectively, Ida’s survival instinct and H. F.’s survival techniques as the plague’s contagion spreads in London.

Ida moves from San Lorenzo because of the Allies’ bombing of the neighborhood. Her movements are determined by famine, fear, and the Nazi occupation.

H.F. movements (sometimes hiding indoors, sometimes wondering about) around the city of London, trace the progress of the plague itself, from the center to the surrounding villages.

In her introduction to A Journal of the Plague Year (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), Cynthia Wall quotes the critic William Hazlitt who in 1830 wrote: “The Journal has an epic grandeur, as well as a heart-breaking familiarity, in its style and matter.” A remark, in my mind, equally fitting for both Defoe’s and Morante’s novels.

The perspective of an oppressed religious minority

Ida Raimundo, the lead character of History, A Novel, is a half-Jew (like Elsa Morante). As such, she bears the brunt of Mussolini’s Racial Laws with unbearable fear, in secret and without the comfort of sharing her persecuted condition with others.

In 1662 the Anglican Church passed 39 articles of faith, known as the Act of Uniformity. Anyone who did not conform to it was ejected from the Church and considered a Dissenter. Defoe’s father was a Dissenter and as such, Daniel, like all non-Anglicans, Catholics and Jews, was prohibited from attending English public schools. His experiences of religious intolerance and persecution are echoed at various moments by his character H. F.’s.

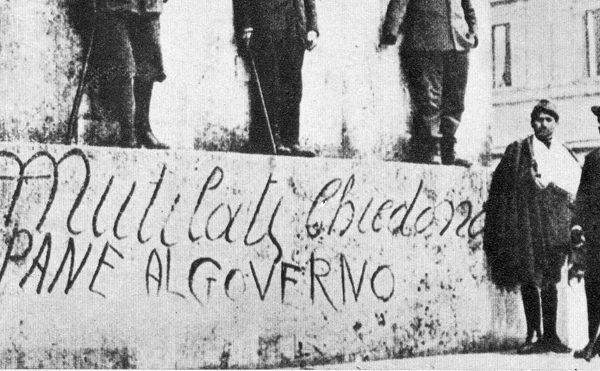

Literature as politics

We know from interviews and conversations that Morante did not want to write a “political novel”, but instead wanted her novel to be a political act. In this too, she may have found inspiration in Defoe’s biography. A journalist for most of his life, Defoe had been employed in numerous different jobs but was always involved in what he referred to as “national improvement”. From 1704, his political engagement became more direct as he continued to publish political essays. He also worked for Prime Minister Robert Harvey in an attempt to promote economic and political union between England and Scotland. Only when his political aspirations failed did he turn to literature as a different way to pursue his goals. He wrote his first novel, Robinson Crusoe when he was already 59 years of age.

In closing

Centuries apart from one another, Morante and Defoe wrote novels that explored the point of confluence between history, fictional storytelling, and chronicle with startling results.

I have no evidence that Elsa Morante ever read A Journal of the Plague Year. But as she accepted the Premio Strega in 1957, for L’Isola di Arturo, she mentions as an inspiration Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Further, in 1936 Elsa Morante met Alberto Moravia (whom she married in 1941). Only the year before, in 1935, Moravia had translated into Italian Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year.

More essays from Elsa Morante’s narrative curated by Alessandro Cassin.