A New Book on the Transit Camp of Fossoli by Liliana Picciotto

Liliiana Picciotto’s new volume – L’alba ci colse come un tradimento. Gli ebrei nel campo di Fossoli 1943-1944, (Mondadori) was presented in Milano’s Sala Della Provincia for the Giorno Della Memoria, on January 27, 2010. The book is a major contribution to the reconstruction of one of the darker chapters of the deportation of Jews and political dissidents in Italy. Ms. Picciotto, one of the principal historians of the Italian Shoah, is Head of Research at the Centro di Documentazione Ebraica Contemporanea in Milano.

The camp of Fossoli, (Carpi) near Modena, in Emilia Romagna, active between December 1943 and August 1944, became the main Italian point of departure toward the death camps for Jews in Italy.

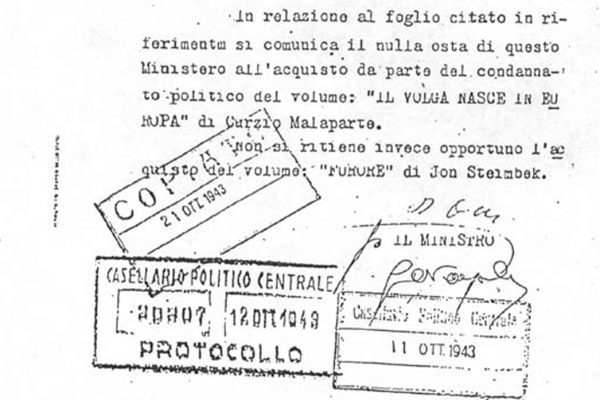

The persecution of Jews, already begun in 1938, escalated in brutality after September 8th, 1943, with the creation of the Reubblica Sociale Italiana in the Center North of the country. From that point on, the Italian authorities adopted anti-Jewish measures as harsh as those of the German occupying forces, (which had also began rounding up the Jews on Italian territory since the autumn of 1943). On November 30, the Repubblica Sociale Italiana ordered and executed the immediate arrest of all Jews, confiscated their goods and interned them in the camp of Fossoli. 2844 Jews were arrested and detained there.

Italian and German authorities divided their responsibilities regarding the camp: the Italians were in charge of the arrests and internment of the Jews in Fossoli, the Germans, who took formal charge of the camp from March 1944 on, organized the transport of the prisoners, in sub-human conditions, from Fossoli to camps in Germany and Poland.

Through a wealth of original research, newly discovered documents and testimonies, Ms Picciotto, reconstructs in detail not only what happened in Fossoli, but how. By weaving together testimonies from former internees, Italian officials, and the local population, this work documents the ultimate betrayal that Italian Jews suffered from their own countrymen.

By including a list of the names of all those interned in Fossoli, and what happened to them, the book becomes also a sort of belated homage to the deportees.

When this impressively well-researched work will be translated in English, it will provide an important contribution to this tragically crucial aspect of the Shoah in Italy.