Islam in the academia. The case of Giorgio Levi della Vida by Miriam Haier

As an Italian Jewish professor in fascist Italy, Levi della Vida completed his groundbreaking work in what was then called “Oriental Studies” while upholding his principles and remaining a role model for his students who did not believe that fascism was the answer for Italy.

On December 19, 1931, Mussolini’s education minister announced that of the hundreds of professors in Italy, only twelve refused to take the newly required oath of loyalty to the Fascist government. According to the education minister, only twelve people refused to accept that “the teaching function should be performed and all academic duties carried out with the aim of producing hard-working, honest citizens loyal to the Fatherland and the Fascist Regime.” While it has been argued that this was an underestimate, it is true that the consequential professional and personal risks were great enough to dissuade most from defying Mussolini. Giorgio Levi della Vida, however, was one man who took the risk. He refused to take an oath “to the King, his Successors and the Fascist Regime” and consequently lost his professorship.

On December 19, 1931, Mussolini’s education minister announced that of the hundreds of professors in Italy, only twelve refused to take the newly required oath of loyalty to the Fascist government. According to the education minister, only twelve people refused to accept that “the teaching function should be performed and all academic duties carried out with the aim of producing hard-working, honest citizens loyal to the Fatherland and the Fascist Regime.” While it has been argued that this was an underestimate, it is true that the consequential professional and personal risks were great enough to dissuade most from defying Mussolini. Giorgio Levi della Vida, however, was one man who took the risk. He refused to take an oath “to the King, his Successors and the Fascist Regime” and consequently lost his professorship.

In addition to no longer having a university appointment, Levi della Vida was in potential danger for having defied the government. Soon after defying the Fascist regime, he moved to the United States and accepted a teaching position at the University of Pennsylvania. One of his students there was Noam Chomsky, who is now Institute Professor & Professor of Linguistics (Emeritus) — Linguistic Theory, Syntax, Semantics, and Philosophy of Language — at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Known for his enormous contributions to the field of linguistics and for his politics, Noam Chomsky remembers the formative influence his professor Giorgio Levi della Vida had on him during his undergraduate years in UPenn. In The Chomsky Reader, he cites Levi della Vida as having made a great impact on him.

Centro Primo Levi recently contacted Noam Chomsky about Levi della Vida. Chomsky said, “I met Giorgio Levi della Vida as a college freshman taking an introductory class in Arabic. It did not take long to recognize that he was a scholar of immense and broad erudition, and a wonderful human being. I stayed in close contact with him until he returned to Italy, and later visited him there. I took all of his courses, and enjoyed the rare opportunity to spend many hours talking to him — more accurately, listening to him — on many topics that were uppermost in my own thoughts, from Semitic linguistics to resistance to fascism and the emerging issues of the early Cold War. His impact on shaping my appreciation of the world of learning, and of a decent life, was very great. ”

In addition to his impact as a teacher, Levi della Vida made significant contributions to what is now known as Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies. According to the Societa per gli Studi sul Media Oriente (SeSaMO) of Florence, Giorgio Levi della Vida “gave a decisive impulse to Islamic and orientalist studies in Italy, giving them the dignity of an autonomous discipline. ” Additionally, he was the first to push for expansion of “Oriental Studies” so that it wouldn’t be limited to linguistics.

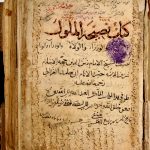

Levi della Vida’s findings and writings also provided crucial information that is still valuable to today ’s scholars. Richard W. Bulliet, Professor of History at Columbia University, told Centro Primo Levi, “In my own case, an article by Prof. Levi della Vida provided the key to a line of research that several scholars have continued to develop since my initial publication. The article was one of a number he wrote in connection with his work on Arabic papyri. It is titled ‘An Arabic Block Print,’ The Scientific Monthly 59 (December, 1943) 473-474. Though less than a page long, and dealing with a document smaller than a playing card, this little article alerted me to the existence wood-block printing in medieval Egypt. ” Thanks in part to Levi della Vida’s discovery and to his own further research, Bulliet was able to “write about medieval Islamic block printing and put it into a plausible social and technological context. ” His findings were published in Journal of the American Oriental Society under the title “Medieval Arabic Tarsh: A Forgotten Chapter in the History of Printing” JAOS, Vol. 107, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 1987), and caused the word “tarsh” to be accepted as a term for block print. This discovery has implications that extend beyond the field of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies: it lends evidence to suggest that print blocking in Europe was “borrowed” from the Arab world instead of China.

Bulliet added, “So in my own case, a chance encounter with Prof. Levi della Vida’s work contributed significantly to a piece of research that I am quite proud of. By ‘chance encounter’, I should perhaps mention that I ran across his article while going through the offprint files of Prof. H.A.R. Gibb after his death. Prof. Levi della Vida had sent it to Prof. Gibb. ” Just as Levi della Vida came from an Orientalist legacy in Italy, so has his work allowed for further exploration and historical discovery.

In the United States today, the name “Giorgio Levi della Vida” is most closely associated with the prize given by UCLA in his name and honor for young scholars who make significant contributions to the field of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies. Established by Professor Gustave von Grunebaum, the award is now known as one of the highest honors in the field. It is fitting, then, that it is named for the Italian Jewish scholar whose legacy reflects his dedication to his field, insistence on its respect as an autonomous discipline, positive influence on his students and his adherence to personal and professional principles. Now a popular and well-respected field of study, Middle Eastern and Islamic studies owes some of its direction to the work of Giorgio Levi della Vida. And scholars and professors of all disciplines can respect his academic and personal integrity.