Let no one praise Perillus, who was cruder than the tyrant Phalaris, for whom he constructed a brazen bull, promising that when a man was enclosed therein and a fire lit underneath, the man would roar like a bull, and who was the first to experience this torture himself as the fruit of a cruelty more just than his own. To such lengths had he distorted a most noble art, intended to represent gods and men, that his numerous workers had toiled only to construct an instrument of torture! Consequently, his works are preserved for one single reason: so that anyone who sees them may despise the hands that made them” (Pliny, Natural History, xxxiv, 19).

Better translations than mine surely exist, but I have a deep personal bond with Pliny the Elder, and I felt that by translating him I was paying him homage. The episode is semilegendary: Pindar, Ovid, and Orosius refer to it, and, following in their footsteps, Dante, in Canto XXVII of the Inferno. Phalaris was the tyrant of Agrigento toward the mid-sixth century bc. Pliny’s phrase “anyone who sees them” seems to indicate that the bull, carried off by the Carthaginians in 403 bc, had been brought back to Agrigentum after the destruction of Carthage, and must have still been there in his time. Nothing is known about the reasons that led Phalaris to burn Perillus in his own bull.

The story, whether true or false, has a curiously modern flavor. For the purposes of a posthumous trial against the tyrant and the artisan, it would be essential to establish with which of the two the initiative and the idea for the horrendous machine originated. If the work was invented by Perillus, and proposed to Phalaris, there is no doubt that Perillus, already famous at the time, deserved to be punished (though not necessarily in that way, and not by Phalaris, who by accepting the object had become the inventor’s accomplice). He had indeed, as Pliny points out, prostituted his art and himself. He must truly have been perverse: it could not have been easy to make the air ducts of the simulacrum the right size such that the victim’s groans would issue from the bronze mouth amplified and modified in their harmonics so as to reproduce the roaring of a bull.

If, on the other hand, Phalaris commissioned the work, the punishment of retaliation that he adopted seems excessive and illegitimate. Still, he was a professional tyrant, and while his actions outrage us, they do not surprise us. All tyrants are capricious. In this hypothesis, Perillus does not come out absolved, but some attenuating circumstances can be conceded; perhaps he had been coerced, or flattered, or threatened, or blackmailed. We don’t know. But his figure as an inventor closely foreshadows modern events and personalities.

The figure of the scientist who is asked to lend his services for the defense of his country, or maybe for the offense against a neighboring country, is a current one. Everyone knows at least something about that prodigious assembly of brains that during the Second World War gave birth to the atomic bomb and, at the same time, to nuclear energy for peaceful use. Some of these scientists went along more or less willingly, more or less convinced; others, after Hiroshima, withdrew to private life; still others, like Pontecorvo*, changed sides for ideological reasons, or perhaps because they thought that nuclear weapons would be less dangerous if shared between the two superpowers.

Happily current today is the figure of the scientist who, after having served power, repents. We read a few days ago that Peter Hagelstein, a student of the bellicose Teller, the young “father” of the space shield, and candidate for the Nobel Prize in Physics, left a laboratory financed by the United States Department of Defense and moved to MIT, where he will deal exclusively with research into the medical applications of the laser. It seems to me that there is nothing to be said in response to this type of conscientious objection: if all the scientists in the world were to imitate Hagelstein, the manufacturers of new weapons would remain empty-handed and universal peace would be closer than it now appears.

The position taken by Martin Ryle leaves me less convinced. Ryle, born in 1918 in England, was one of the greatest radar experts during the war, and made decisive contributions to the measures adopted by the British to “confuse” the German radar. After the war, sickened by the horrors of combat itself, he decided to continue his brilliant career as a physicist in a field that lent itself less to military applications, namely, radio astronomy. He was awarded the Nobel in 1974; but he must have realized soon enough that not even his astronomer colleagues had perfectly clean hands. For example, measuring the intensity of the gravitational field around the Earth with precision is unquestionably of theoretical interest, but it also serves to better guide intercontinental ballistic missiles. According to Ryle’s data, 40 percent of Britain’s engineers and physicists are engaged in research involving instruments of destruction.

Shortly before his death, in 1984, Ryle formulated a drastic proposal: “Stop science now”—let’s cease all scientific research immediately, even that which is called “basic.” Since we are incapable of predicting how any discovery might be distorted and exploited, let’s just stop: no more discoveries.

While I understand the spiritual torment from which this appeal sprang, it seems to me to be extremist and utopian at the same time. We are what we are: every one of us, even the farmer, even the most humble craftsman, is a researcher, and always has been. We can and we must defend ourselves in other ways from the danger undeniably inherent in any new scientific knowledge. It is quite true, as Ryle says (and I quote), that “our cleverness has grown prodigiously—but not our wisdom”; but I wonder how much time, in all the schools, in every country, is devoted to increasing wisdom, that is, to moral issues?

I would like to see (and it doesn’t seem either impossible or ridiculous) all scientific faculties emphasize this point to the utmost: that whatever you do when you practice your profession can be useful for mankind, or neutral, or harmful. Don’t become enamored of dubious problems. Within the limits allowed, try to learn the purpose for which your work is intended. We all know that the world is not made up solely of black and white, and your decision may be probabilistic and difficult; but you will agree to research a new medicine, and you will refuse to devise a nerve gas.

Whether you are a believer or not, whether you are a “patriot” or not, if given a choice, don’t let yourself be seduced by material or intellectual interests but choose from among those which can render the journey of your contemporaries and of your descendants less painful and less dangerous. Don’t hide behind the hypocrisy of neutral science: you know enough to be able to assess whether a dove or a cobra or a chimera or perhaps nothing at all will emerge from the egg that you are hatching. As for basic research, it can and must continue; if we were to abandon it, we would betray our nature and our nobility as “thinking reeds,” and the human species would no longer have any reason to exist.

* Bruno Pontecorvo (1913—1993) was an Italian nuclear physicist who worked in Canada during the war and then became a British citizen. In 1950, he defected to the Soviet Union.

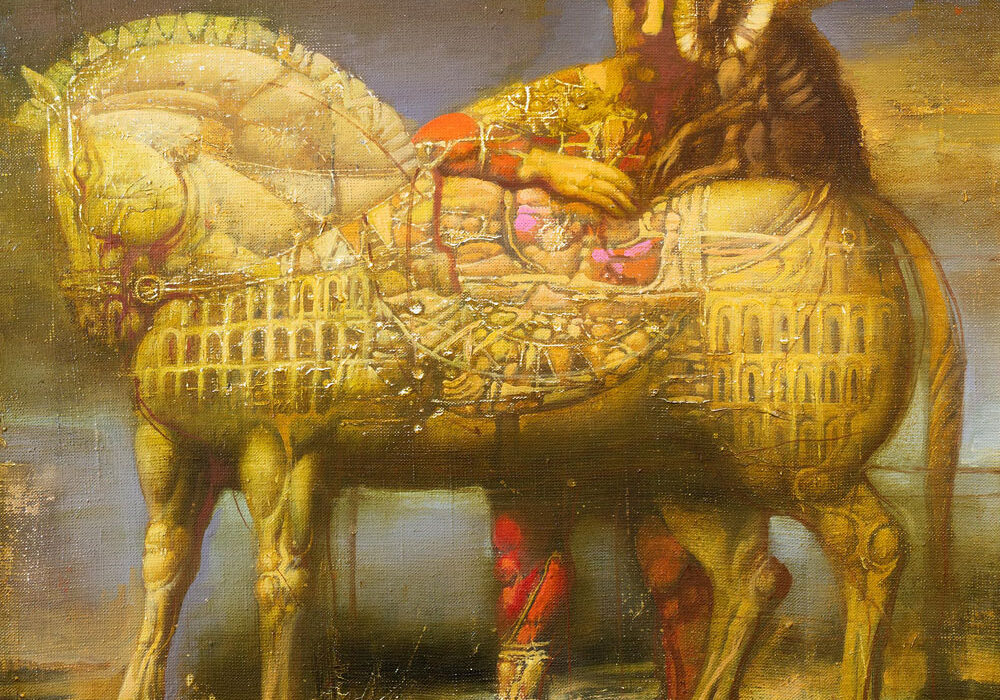

Image: Armen Gasparyan, Trojan Horse, oil on canvas