Among the always impressive roster of exhibitions on display in Rome, La Menorà: Culto, Storia e Mito (The Menorah: worship, history, and myth), stands out for its far-reaching symbolic, cultural and political dimensions.

With a closing date of July 23rd, it’s a must for anyone in Rome or about to go there.

The show marks the first collaboration ever between the small yet formidable Jewish Museum of Rome and the lavishly extensive Vatican Museums. This collaboration can auspiciously open new grounds in the 21 Century long relationship and interdependence — often wrought by taxing, oppressive and irreconcilable positions —between the Catholic Church and Jewish Community of Rome.

Conceived by Alessandra Di Castro, Director of The Jewish Museum of Rome with Antonio Paolucci Director of the Vatican Museum, succeeded, months before the opening, by Barbara Jatta, over a three-year preparatory stage, the exhibit came together through the efforts of a dedicated curatorial team spearheaded by Alessandra Di Castro, Arnold Nesselrath and Francesco Leone.

The project stems from a smaller show, From Jerusalem to Rome and Back: The Menorah’s Journey Between History and Myth, conceived in 1998 by the late Daniela Di Castro, then director of Rome’s Jewish Museum, and exhibited in Jerusalem.

Despite the complexities and high stakes, the most stunning achievement of the creators of this epoch-making event is that of grounding the discourse on exquisitely art-historical grounds. Beyond, interfaith dialogue, religious belief, legend and lore, the exhibit explores the intricacies of the journey of the menorah, through 130 important artifact— sculpture, painting, textiles, decorative arts and archeological finds— ranging from antiquity to today.

In addition to treasures from the two presenting institutions, La Menorà: Culto, Storia e Mito, assembles works, never previously shown together, on loan from major museums from across, Europe, Israel, and the US.

The story and artistic renditions of the menorah, first described in the Book of Exodus as the candelabrum ordered in accordance with the Lord’s precise instructions to Moses, to be forged in pure gold, provides the gripping narrative that, as the title suggests, juxtaposes worship, history, and myth.

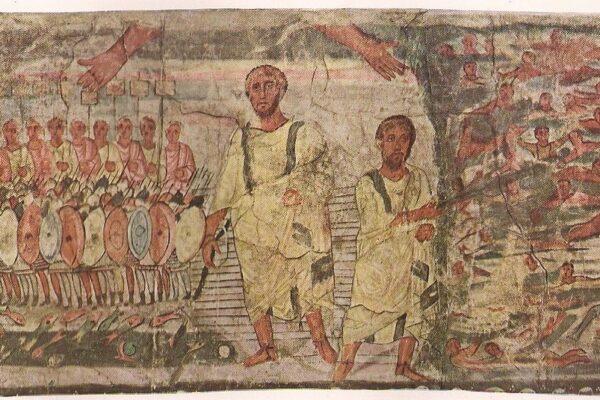

Accordingly the two main section of the exhibit focus respectively on the ancient history of the menorah from its place in the Temple of Jerusalem through its transport as war spoil to Rome, where it “disappeared”; on the journey of the menorah, through time with a specific emphasis on its appropriation by Christianity, and on its transformation into an enduring symbol of Jewish cultural identity.

Against the backdrop of the menorah’s disappearance, the counterpoint of art and history reinforces the power of this object and – as Alessandra Di Castro states in the catalog, become “means of universal dialogue”. A dialogue which unveils that things may not always be what they appear to be and that one story is, in reality, many.

Archeologist Samuele Rocca, quoting the groundbreaking work of Umberto Cassuto, suggests that the celebrated flat bi-dimensional object we call “menorah” may be a product of Hellenistic culture. In fact, our menorah is quite different from the earliest menorah, a ritual round cup, made of gold, which stood on a central high pedestal decorated with a knob, almond flowers, and pomegranates.

Interestingly, Rocca points out, it was not until the 4th century, following the rise of Christianity as state religion, that the stylized bi-dimensional menorah began to appear pervasively in Jewish iconography as a symbol of Judaism. It spread first in Roman Italy and then in Palestine and throughout the Mediterranean where it slowly replaced imageries that Jews shared with pagan cultures.

The multi-layered legends around the disappearance of the menorah, which range from its destruction by the Vandals, it’s hidden permanence in Rome or drowning in the Tiber to its travel abroad, continue to ignite our imagination to this day.

Although there is no evidence that the menorah was still in Rome past the end of the 2nd century, the most intriguing part of its history begins with Charlemagne’s ascent to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire, in the year 800. Charlemagne traced his ancestry to Rome and Jerusalem and made the menorah and Solomon’s Temple emblems of the Christian empire.

The lost treasures of the Temple became central to the narrative of the crusades and in the last decade of the 1200 the Tabula Magna Lateranensi, a mosaic inscription in the sacristy of St. John Lateran, listed the seven branches candelabrum among the relics from Jerusalem held in the basilica.

It is at this point of its journey, that the menorah’s relationship with its origin in Judaic antiquity began to fade.

Few stories linking a physical object to the fate of a people can rival the beauty and poignancy of that of the seven -branched candelabrum. Legends around its disappearance have continued to flourish into the present times, the constant retelling perhaps serving to keep the legend alive. In his novella, The Buried Candelabrum, Stephen Zweig, goes a step further. The compelling plot links destruction of the Second Temple and the beginning of the Jewish diaspora with the second sack of Rome by the Vandals, and further, to the menorah’s travel to Carthage and to Constantinople. In 1937, a year from the Anschluss, Zweig —one eye on the distant mythical past, the other on the near future— in describing the efficient and bureaucratic sack of Rome by Genseric’s Vandals, foreshadows, with arresting precision Field Marshal Kesselring leading the Nazi occupation of the Eternal City.

All the multi directional/temporal suggestions we have alluded to, and more, emerge distinctly from a close visit to La Menorà: Culto, Storia e Mito. Walking through the galleries one is captivated by beautifully lighted works of art that attest to the degree to which the image of the menorah through the ages has been linked to the Temple of Jerusalem, the beginning of the Diaspora and more in general to the history of the Jews. But it’s only upon reading the insightful scholarly essays featured in the handsome bilingual catalog of the show, that one fully grasps the full scope of this one of the kind exhibit.

The exhibit takes place both in the Jewish Museum of Rome and at the Braccio di Carlo Magno in the Vatican City, with its handsome poster hanging over the entrance, along Bernini’s colonnade in Saint Peter’s Square. One can hope that this fruitful collaboration between the Vatican Museums and the Jewish Museum of Rome will be a blueprint for future cultural exchanges between the two sides of the Tiber.