Homens da Nação: the « Portuguese » of Livorno and Tunis

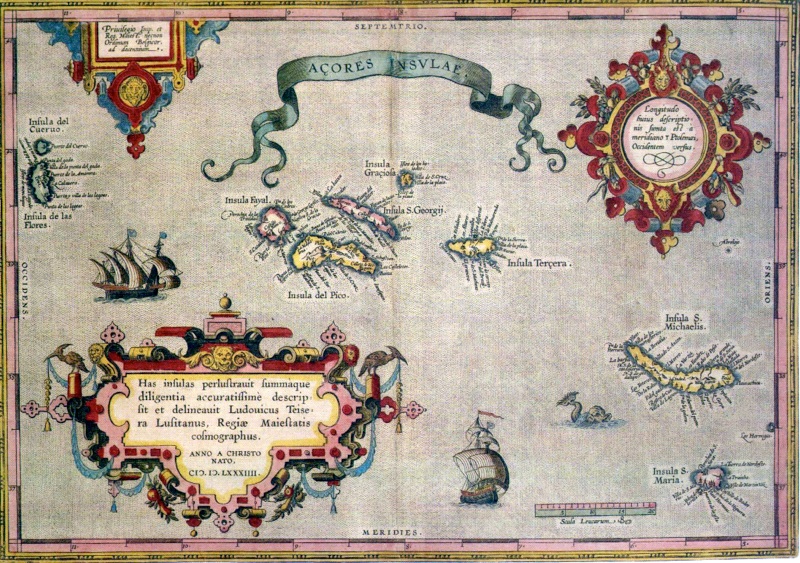

From a very young age, I knew I was a Livornese, but I only went to Livorno for the first time a few years ago. From the window of my room in the Hotel Gran Duca, I could see the old harbor, the Darsena Vecchia. It was there in 1614 that Rodrigo Cardoso – probably my maternal ancestor – arrived from Egypt aboard his ship, the N.S. Della Bonaventura¹³. During the same period, the galleon of Nathan Nunes was trading between Livorno and Tunis¹³; for these New Jews – the former New Christians – from Livorno had ships all over the world, and were to be found sailed in and out of every harbor in Europe and the Mediterranean from Amsterdam to London and Hamburg, and from Tunis to Aleppo and Istanbul. The esteemed French historian Fernand Braudel, coined the phrase ‘the maritime Empire of Livorno’ to describe the extraordinary reach of these merchant ships9. We don’t know exactly how many ships the New Jews of Livorno owned but in Curaçao, the Dutch island of the Caribbean, at least 2000 boats are known to have belonged to Iberic Jews; and more than 200 Captains acknowledged. In Portuguese, Jews were known as Homens da Nação, (Men of the Nation). They were also identified as Cristãos Novos (New Christians), Marranos, or Conversos – the latter a reference to their forced conversions to Christianity in both Spain and Portugal l5,11.

The Inquisition accused and indicted Jews on charges of having for centuries engaged in what they termed Judaizing in secret; many were consequently imprisoned, tortured, burned alive and had their property summarily confiscated. Several hundred thousand were forcibly converted.

About 20.000 managed to escape to places all across the Old and New Worlds, but only 200 families chose to return to practice their Judaism in Amsterdam, Livorno, and other European countries. These newcomers to Livorno had Spanish or Portuguese13,19,23names and married within their own community for at least four centuries. They spoke Spanish at home and Portuguese for business. Eventually, however, their everyday language became Italian and they were the only Jews in the world to have full rights of citizenship as early as the end of 16th century.

The Darsena Vecchia – the old harbor – was connected to the main street of Livorno, the Via Ferdinanda, named after Ferdinando de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany at the end of the 16th century. It was Ferdinando who granted Tuscan citizenship to a group of wealthy New Christians and permitted them to return openly to the faith of their fathers. 12,13,23 According to the Livornina, the Charter of Tolerance – which became law on June 10, 1593 on the authority of Grand Duke Ferdinand – the New Jews could establish their own laws, trade freely and award equal rights to their daughters and sons in business, marriage and divorce. But perhaps most importantly, they would be living in an open city and not confined to a ghetto like other Italian Jews Italy in Florence, Sienna, Venice and Rome22. These New Jews were free to settle anywhere in Tuscany.

They were also very wealthy. It is said that Righetto Nunes lost 70,000 ducats playing cards with Ferdinando de’ Medici12; and a Nunes was reputed to have sold merchandise in Florence to the value 40,000 ducats15. These were considerable amounts when compared to the mere 900 ducats paid for the entire construction of the splendid 17th century synagogue of Livorno.

The main source of the wealth of this small community of Portuguese Cristãos Novos was the spice trade, which flourished along the new maritime route round the Cape of Hope opened by Vasco de Gama in the 16th century11. But there was poverty too among the Livorno Jews. The poor came mostly from Rome, a few other Italian cities and from North Africa. These newcomers were usually given some money before being asked to leave the city.12,19,23

Young Ashkenazi girls were occasionally hired as servants and could earn a dowry after working in Livorno. But marriage between a Tedesca – a German or Polish girl – and a young Livornese was forbidden. Love was punished by the exile of both young partners. It should be remembered that the Livornesi were frequently quite pretentious – calculating the extent of their nobility in direct proportion to the amount of Spanish ‘blood’ they had.

As we will see later, in Tunisia local Jews spoke a Judeo-Arabic dialect; they were very poor and mostly wore only the djellaba (caftan) and a black chechia (traditional men’s cap); they could not believe that the Livornesi, with their silk shirts and crimson and black capes, were Jews. Records from the State Archive of Livorno help us understand how the Portuguese community settled into the city and organized. We know that an Antonio Nunes, son of Dominic, arrived from Portugal and bought a warehouse one block from the harbor19. Antonio had probably been baptized previously, but at the corner of the same street one can also find the warehouse of Abraham Nunes and his sons, David, Moses, and Jacob13. From the beginning of the 17th century, all newcomers took Hebrew first names while keeping their Iberic surnames.

This is what happened with Nunes’ relatives: the Morenos, Boccaras, Medinas, Sorias, Lumbrosos, Mendes’ and Francos. In the register of the Jewish Community recovered from the ruins of the synagogue destroyed during World War II, the names Nunes Abravanel and Nunez Mendes were still to be found; and as Aaron Leone Leoni points out in his beautiful book on the Spanish Community of Ferrara, the Nunes’, Benvenistes, Abravanels and Mendes’ had been prominent Jewish Spanish and Portuguese families in their countries of origin17. There are also documents in the State Archives concerning the institution of Jewish charities.13,19,23 One charity was established to help the poor and the disabled – mainly Jews who had fled other Italian cities and their ghettos.

The Massari – the leaders of the Livornesi Jews – were reluctant to let poor Jews dwell in the city, while wealthy families such as the Recanati from Rome and the Bacri from Algeria were welcomed enthusiastically. Another charity, named HaMerah Betoulot or Hebra para cazar Doncellas, was established to give a dowry to orphan and indigent Jewish girls from countries as remote as Poland or Turkey.13,19,23

HaMerah Betoulot was particularly interesting. It was a society funded by financial contributions from the wealthiest merchants of Livorno, generated by a portion of the insurance paid on ships and their merchandise sailing in and out of Livorno that was not distributed to the shareholders but used for charity instead. The dowry brought by a spouse was the principal form of inheritance, and essential in that it allowed a young couple to start their own business. When the husband died the dowry reverted back to the widow who was also authorized to continue the business on behalf of her children.14 A third charity was created to buy freedom for Jewish slaves captured by pirates.13,19,23

Pirates were to be found all over the Mediterranean Sea. Not just those arriving from North Africa – like the notorious Barbarossa – but also many of English, French and Turkish descent. Tuscany itself had a pirate fleet – La Compagnia di Santo Stefano – whose ships sailed to the coast of North Africa to bring back Muslim slaves to be sold in Livorno. The Livornesi Jewish merchant ships were often asked to go to Tunisia to bring back European slaves captured on the coasts of France and Italy. After the Crusades, Christian merchants were not welcomed in Muslim countries while the Jews from Livorno were accepted: the Lumbroso family, for instance, specialized in this kind of trade.8 The Portuguese community of Livorno grew little by little as Jews arrived from other Italian cities, from North Africa and later from the Ottoman Empire, Greece and Turkey – as evidenced by names listed in the census of 1809.12

On the whole these different groups integrated pretty easily but all remained proud to be Livornesi even centuries after moving to other countries. They continued in international trade for at least two centuries and created assorted industries including glass, soap and sugar. They were importing wool, leather, wheat, and all kinds of goods from Spain, Portugal and the Muslim countries; and exporting the products of their industries.12 For instance wool coming from abroad was used in Livorno by the Cardoso family to make the Chechia and the Fez Stanboulia – the red hats widely used throughout the Ottoman Empire and across the Muslim world.

They also printed books in Hebrew that were distributed all around the Mediterranean. But things changed when French troops led by Napoleon Bonaparte arrived in Tuscany following the revolution of 1789 and, later, with the creation of the kingdom of Italy.12 The statute of a free port was abolished and all trading activity was severely curtailed during the continental blockade by the British. Yet the Jews of Livorno welcomed the ideas of the French revolution and many became members of the Free Masonry – a decision that would make things difficult for them later following the departure of the French and subsequent return of the Grand Dukes of Tuscany.

The Departure towards the Muslim world

Impoverished by circumstances in Livorno and fearful of the riots organized by fanatical priests,13 many families of Spanish origin decided to emigrate to Muslim countries.

The Livornesi had maintained commercial and familial ties with Muslim countries since the times of Moorish Spain and many had spoken Arabic for centuries. These strong links with the Muslim world was conceivably one of the reasons the astute Medici had fostered the Livornesi and facilitated ongoing and fruitful trade with North Africa and the Ottoman Empire.

As early as the 16th century, one could find in Tunis a chief Rabbi named Lumbroso and, among others a trader merchant, Jacob Nunes who also kept a house in Livorno; another Nunes had houses in Rosetta, Egypt and Aleppo, Syria.23 The long-standing bond between Livorno and Tunis was further strengthened by an episode involving the Medici who asked that the New Christians arriving from Spain travel to Tunis for the ritual of circumcision.13,22

This was done to avoid the resentment of the Inquisition in nearby Pisa and Rome, who were always keen to punish the apostates – as New Christians returning to Judaism were considered.

Worth noting too is that the Livornina granted the English, the French and the Dutch the same privileges as the Jews – as Naçãos (Nations).12

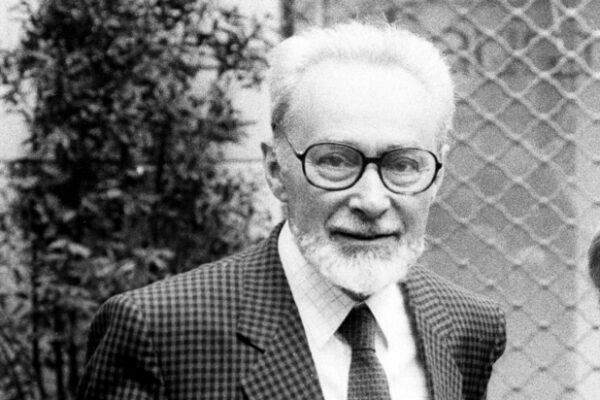

Fernand Braudel9 suggests that the naval power of England began in Livorno. The Livornesi spoke several languages including Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and Arabic; but also French, English and Hebrew. They were often asked to act as interpreters for merchants trading between Europe and the Middle East.

All this helps us better understand why Tunis was the city the Livornesi chose to settle in at the end of the 18th century and why they remained there till the end of World War II. Tunisian ketubot (marriage contracts) show the names of the Livorno families of Tunis as early as the end of the 18th century.3,4 The Suq El Grana is the neighborhood of the Livornesi in the Medina – the old town of Tunis (Grana means Livornesi in Arabic). The Portuguese community of Tunis was distinct from the Tunisian community and they maintained separate synagogues and cemeteries. The two communities shared both friendly relations and conflicts.6,8,9,17,19,20,21

The Tunisian Jews (the Touansa) considered the Livornesi to be Rkirk, pretentious. The Livornesi, for their part, believed the Touansa to be uncivilized. It was true that there were big differences in wealth and customs between the two populations. Yet the sovereigns of Tunis – the Beys – welcomed the Livornesi, who brought innumerable skills as international traders, administrators, physicians, industrialists etc. A Livornese, General Valensi, even became the Commander in Chief of the Tunisian army; while a trader, Emmanuel Nunez, was Minister of Finance.

A survey established by the Italian government in 1943 shows that 80% of Tunisian industry belonged to Livornesi families. The Livornesi became the cultural and economic leaders19 of Tunisia’s larger Italian population – composed mostly of Sicilians who came to escape the acute poverty of their island. A Moreno was President of the Dante Alighieri – the Italian cultural society and also of the Italian Chamber of Commerce.

A Nunez was president of the Italian charity for the poor and remained a member of the HaMerah Betoulot in Livorno till the end of the 19th century. A Calo was responsible for a charity that cared for newborns, irrespective of their ethnicity.

Maurizio Cardoso was Director and chief surgeon of the Italian Hospital Garibaldi and of the Israelite Hospital. Most Livornesi were wealthy and several owned banks. But they gradually withdrew from business and before the independence of Tunisia, all Livornesi were physicians, lawyers, scientists and teachers, all trained in Italian and French Universities. The Livornesi in Tunis were Italian patriots still grateful to Tuscany and, later, to Italy for having been so generously welcomed after the terror of the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisition.19

Jewish charities addressed the needs of the poorer and often illiterate Tunisian Jews who lived in a confined area called Hara, but also of peasants and working class Sicilians living in the neighborhood named la Piccola Sicilia (Little Sicily) where entire families lived in one cramped single room. The Livornesi continued to prosper In Tunisia even after the French took power at the end of the 19th century. However, with the promulgation of Mussolini’s racist laws in 1938, Livornesi children began to be chased from the Italian schools.19 French schools accepted them willingly but a new chapter of discrimination began two years later with the anti-Semitic laws of Marshall Petain.2,18

Things deteriorated further with the arrival of the Nazis, who occupied Tunisia after the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942.6,19

Young Jews were submitted to forced labor,7 the Jewish community had to pay huge fines and several prominent members of the community – mainly Livornesi – were imprisoned as hostages.

Some were deported to Auschwitz. Fortunately the German occupation of Tunisia was short-lived. In May 1943 the Allied armies defeated the Germans and liberated Tunisia. After the liberation, the situation remained difficult for the Livornesi. Now they were considered to be Italians and enemies of France by the same administration that had established the anti-Semitic laws of Petain just two years before.1,18,19

Two hundred Livornesi were put under house arrest in the South of the country.1,2 Physicians were prohibited from treating patients, houses were confiscated and many other severe penalties imposed.

Fortunately, the intervention of the American Embassy and the Free Masonry stopped much of this new and unexpected persecution. Nevertheless, the vast majority of the Livornesi chose to become French and gradually they fully integrated into French society.

Ironically, following the independence of the country, all non-Muslim inhabitants of Tunisia, both Jews and Christians, were forced to leave. Everywhere, Portuguese communities as a distinct entity have disappeared. In Livorno one finds Jews from Libya and other Italian cities, but only a few of Spanish origin. In Tunisia the Jewish population is close to zero1 with not a single Livornese remaining. Half the Tunisian Jews – the Touansa – are now in France, while the other half live in Israel. In both countries, they are often physicians, lawyers, scientists and teachers and have advanced and prospered in less than two generations.

Today, the Livornesi can be found in Italy, France, the United States and some in Israel. Only a few of them are traders nowadays but some are still as pretentious as they ever were.

LINKS

Arthur Kiron, Dust and Ashes, The Funeral and Forgetting of Sabato Morais

Arthur Kiron, Livornese Traces in American Jewish History: Sabato Morais and Elia Benamozegh

Francesca Bregoli, The Port of Livorno and La Nazione Ebrea in the Eighteenth Century: Economic Utility and Political Reform

James Nelson Novoa, The Departure of Duarte de Paz from Rome in the Light of Documents from the Secret Vatican Archives

Bibliography

1. Abitbol Michel. Le Passé d’une Discorde: Juifs et Arabes depuis le VIIe siècle. Editions Perrin,1999

2. Abitbol Michel. Les Juifs d’Afrique du Nord sous Vichy. Maisonneuve et Larose ,1983

3. Attal Robert et Avivi Joseph. Registres Matrimoniaux de la Communauté Juive Portugaise de Tunis au XVIII et XIXe siècles., Institut Ben-Zvi Jerusalem,1989

4. Attal Robert et Sitbon Claude. Regards sur les Juifs de Tunisie. Albin Michel, 1979.

5. Baer Yitzhak. The History of the Jews in Christian Spain. The Jewish Publications Society,1992.

6. Balta Paul, Dana Catherine, Dhoquois-Cohen Regine. La Méditerranée des Juifs: Etudes et enracinements. L’Harmattan Editeurs, 2003.

7. Bismuth Victor. La Marche de la Mort du Jeune Gilbert Mazouz

8. Boccara Elia: La Comunita Ebraica Portoghese di Tunisi (1710-1944), Rassegna mensile di Israel # 2, 2000

9. Boccara Elia. Refus d’identité: Livournais et Tunisiens. Genami #47, March 2009

10. Braudel F., La Mediteranee et le Monde Mediterranee en l’epoque de Philippe II. Armand Coli Ed., 1990

11. Carsten L. Wilke. Histoire des Juifs Portugais. Chandeigne editeur, 2006

12. Filippini Jean Pierre. Il porto di Livorno e la Toscana (1676-1814) (Volumes I, II et III.) Edizioni scientifiche Italiane, 1998

13. Frattarell Fischer Lucia. Vivere fuori dal Ghetto: Ebrei a Pisa e Livorno (secoli XVI-XVII). Silvio Zamorani Editore, 2008

14. Galasso Cristina. Alle Origini di una Comunita. Leo S. Plschki Editore, Firenze

15. Goldberg E. Jews and Magic in Medici Florence, The Secret World of Benedetto Blanis, University of Toronto Press, 2011

16. Guetta Alessandro, Philosophy and Kabbalah: Elijah Benamozegh and the Reconciliation of Western Thought and Jewish Esotericism, SUNY Press, 2009

17. Leone Leoni A. La Nazione Ebraica Spagnola e Portoghese di Ferrara, (1492-1559), Olschki Ed. 2011, Firenze

18. Levy Lionel. La Nation Juive Portugaise, Leivourne, Amsterdam, Tunis, 1591-1951 L’Harmattan Editeurs, 1999

19. Nataf Claude. Les Juifs de Tunisie face à Vichy et aux Persécutions Allemandes

20. Nunez G. Delle Navi e degli Uomini: Da Toledo a Livorno a Tunisi, Salomone Belforte Editori, Livorno, 2011

21. Sebag Paul. Histoire des Juifs de Tunisie. Paris, L’Harmattan Editeurs, 1991

22. Sebag Paul, Les Juifs de Tunisie, Origines et Signification, Paris. L’Harmattan Editeurs, 2002

23. Sigmund Stephanie, The Medici state and the Ghetto of Florence, Stanford University Press, 2006

24. Toaf Renzo, La Nazione Ebrea a Livorno e a Pisa (1591-1700), Leo Olschki Ed. 1990

25. Trivellato Francesca, The Familiarity of Strangers: The Sephardic Diaspora, Livorno, and Cross-Cultural Trade in the Early Modern Period, Yale University Press, 2009