Edith Bruck, This Darkness Will Never End, Paul Dry Books, 2025, Translated by Jeanne Bonner | 187 pp.

In 1944, at the age of 13, Edith Bruck was deported to Auschwitz. She was then transferred to Dachau, Christianstadt, Landsberg, and finally, Bergen-Belsen, where she was liberated by the Allies. In This Darkness Will Never End, her first short story collection, originally published in Italy in 1962 as Andremo in città (“We’ll Go to Town”) and now translated into English for the first time, there is not a single mention of the Holocaust.

Its absence defines the collection. The stories mainly take place in the years before the war, in villages and homes where hunger is ever-present, where children sneak moments of joy, and where the menace of the future looms, still unknown, but closing in. These are stories of childhood—its innocence, inquisitiveness, disappointments—and of parents, overworked and exhausted, but giants in the eyes of their children. In reality, they are just as helpless against history.

Bruck was born in 1931 in the small village of Tiszabercel, Hungary, and grew up in poverty. She lost both her parents as a young child in the camps—her mother in Auschwitz and her father in Dachau. She dedicates the book to her father: “Who got nothing from life, and undeserved ridicule from us.”

Bruck was born in 1931 in the small village of Tiszabercel, Hungary, and grew up in poverty. She lost both her parents as a young child in the camps—her mother in Auschwitz and her father in Dachau. She dedicates the book to her father: “Who got nothing from life, and undeserved ridicule from us.”

Indeed, fathers appear again and again in these stories, as do mothers. Almost every story begins with “my mother” or “my father” or both, if not in the first paragraph, then certainly by the second.

In The Frozen River, the collection’s first story, Erika, a young girl from a poor Jewish family, falls in love with Endre, a Christian boy from the city. Her family cannot afford to send her to school, so while Endre studies, she does chores—such as washing clothes in the frozen river. She must use a hatchet to break the ice. It is there, under the trees by the river, that the two teenagers meet in secret. One day, Endre tells her they have to stop. He does not say why, but she understands. “They’re fine people, just a little untrusting toward us,” her mother tells her.

This is how antisemitism functions in these stories: through the eyes of children or adolescents attempting to understand the world around them. Antisemitism is never explicitly made central, but is instead a force that enters and disrupts the lives that the characters had hoped to live.

That Bruck tells these stories from the perspective of children without the comfort of an omniscient narrator makes her narratives all the more powerful. In the eponymous story, which some scholars argue was an inspiration for Roberto Bengnini’s 1997 film Life Is Beautiful, a young girl, Lenke, takes care of her blind brother, Beni. When the Nazis arrive to take them away, she lies to him. She tells him they are being helped because they’re orphans, and that “there are a lot of people in need of help and they [the Nazis] don’t want it widely known… That’s why they’re acting rude and annoyed.” When he asks her about the train, she tells him it is elegant, with red velvet seats and white curtains.

The story that follows, Silvia, is about a different child who does not understand what he is witnessing. Robert is the son of a Nazi officer. He throws snowballs at passing trains until one day he hears voices—men, women, children—crying from inside. But his mother refuses to explain. Undeterred, he returns to the trains and stumbles into the nearby forest, where he finds a girl sobbing, buried in the snow. He carries her home and announces: “Here’s a daughter for you and a little sister for me. You always wanted a little girl named Silvia. From now on, we’ll call her Silvia.”

His mother is horrified. His father locks her in a bunker. Soon, the parents die in an Allied bombing and only Robert and ‘Silvia’ survive. Silvia has a sign around her neck: “Miryam Lewy, Born 1939, Budapest.” When a Red Cross worker asks for their names, Silvia scratches out her given name and rewrites it with her new one. She tells the Red Cross worker that Robert’s last name is Lewy, and then turns to him: “You’re my brother, right?”

These two stories form a striking diptych: In the first, one child saves another from the knowledge of horror; in the second, one child saves another without knowing the horror.

Poverty permeates the collection. It appears in every detail—never enough food, worn-out shoes, shared beds, endless chores. In At the Foot of the Bed, siblings take turns sleeping at their parents’ feet, because there aren’t enough beds. In The Verdict, a mother is frightened every week of the shochet’s verdict: will the meat be considered tref (not kosher), leaving the family without enough to eat? (A shochet is one certified to slaughter animals according to Jewish tradition.) In My Father’s Horse, a father buys a sickly horse with the family’s meager savings only to have it die immediately, leaving the family worse off than before.

This crushing poverty creates a peculiar fascination with funerals—especially with the contrast between those of the rich and of the poor. One young narrator describes her “favorite pastime” as “following the funeral processions of the rich.” She continues: “A poor person’s funeral isn’t any fun… A bony horse would drag the cart with the casket through the town, and the people who came out to look would go right back inside… In the summer, there were wooden crosses, but come winter, they would be stolen to burn in the stove.” These children observe death with a closeness that foreshadows what is coming.

In Come to the Window, It’s Christmas, Bruck captures a moment of terror in just a few pages. A girl waits excitedly for friends to sing Christmas carols under her window. Instead, she hears shouting in a foreign language. Then, a clear: “Heil Hitler!” The parents panic, and believing they’re about to be deported, quickly pack a suitcase. The girl rushes to the window and sees her friends laughing, Hitler mustaches drawn on their faces. Afterwards, the girl asks her father:

“It was a joke, right, Papa? Just a joke.”

“Yes,” he replies. “Now we can sleep.”

Bruck’s prose is direct and spare, free of sentimentality, and Jeanne Bonner’s translation preserves this clarity. When I spoke with Bonner, I asked why Bruck chose to write these stories in Italian. Nearly all take place in Hungary, and Hungarian was her first language—was it simply because she lived in Rome? Bonner, who met with Bruck many times during the work of translation, told me that Italian served as a “linguistic buffer” for her—a way to write about these memories without reliving them in Hungarian. Bonner continues to translate Bruck’s work.

After the war, Bruck briefly returned to Hungary, then lived in Czechoslovakia and spent three years in Israel before arriving in Italy in 1954. She settled in Rome, where she married filmmaker and poet Nelo Risi and still lives and writes today at the age of 93. Adopting Italian as her literary language, she wrote more than thirty books and worked in theater, film, and television. Her contributions to Italian literature and Holocaust testimony have been widely recognized.

With this collection, written at the beginning of her illustrious career, Bruck delivers an elegy—for childhood, for parents lost too soon, and for a world that once existed.

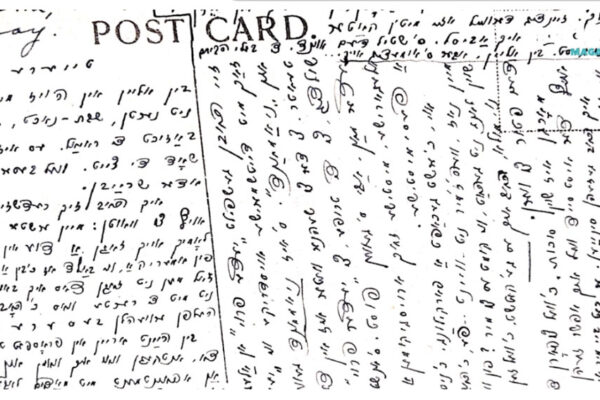

Image: Edith Bruck, Digital Library, CDEC, Milan