Between June and October 2014, an exhibition entitled Artiste del Novecento tra visione e identità ebraica [Women Artists of the Twentieth Century/Vision and Jewish Identity] was held at the Galleria D’Arte Moderna di Roma [Order Catalogue at fondazione@ucei.it].

Cynthia Madansky is an artist that makes films which engage with cultural and political themes, such as identity, nationalism, the transgression of borders, displacement, nuclear arms and war foregrounding the human experience and personal testimony, giving voice to narratives that are usually marginalized. Madansky’s work portrays the consequences of politics on the daily lives of individuals, creating intimate portrayals of people living in very complex situations, focusing on issues of US foreign intervention and interrogating the concept of responsibility. Her award winning films have been shown as single-channel works and multi-channel installations at numerous international venues including, the MoMa, NYC, The Istanbul Modern, Walker Art Museum, The Berlin Film Festival, Rotterdam Film Festival, Cinema du Reel, Paris, Tehran Film Festival, India 30 City Peace Festival and Homeworks, Beirut. She is currently a Visual Arts fellow at the American Academy in Rome working on E42 a film about the Esposizione Universale Di Roma.

Giulia Mafai is the youngest of three daughters of Mario Mafai and Antonietta Raphäel. She is a stage and costume designer and worked in many prominent film productions. Her collaborations include Vittorio De Sica, Mario Monicelli, Elliot Gould, Harvey Keitel and Keith Carradine. Between 1978 and 1985 she has been a curator for the Laboratorio del Carnevale di Venezia. She has curated art exhibits in Italy and aborad. Her book La ragazza col violino is dedicated to her mother.

The exhibition magnificently curated by Marina Bakos, Olga Melasecchi and Federica Pirani included painting and sculpture by Twentieth Century Jewish women artists, some well known with strong international careers, and others who were as committed to their artistic practice whose work was rarely seen by the public.

In many ways this curatorial collaboration was a monumental exhibition, displaying an intimate and rarely seen juxtaposition of Jewish artists from the Novecento movement and providing insight to their diverse artistic influences, concerns and practices.

Artists represented in the show include Antonietta Raphäel, Adriana Pincherle, Paola Levi Montalcini, Eva Fischer, Paola Consolo, Gabriella Oreffice, Silvana Weiller, Annie Nathan, Liliah Nathan, Pierina Levi, Amalia Goldmamm, Wanda Coen, Corinna and Olga Modigliani and Amelia Almagià.

On the occasion of this exhibtion, Giulia Mafai presented her new book entitled La Ragazza Con Il Violino on the work of her mother Antonietta Raphael (1985 c. – 1975).

Antonietta (Nekhomà) Raphäel was born in Kovno in 1895. In 1905, she moved, with her mother, to London where she studied painting, drawing, music and singing. After leaving London she stayed briefly in Paris before settling in Rome in 1924. Her work has been shown in international galleries and exhibitions including the Venice Biennial, Galleria Zodiaco and the 8th Quadrennial of Rome. Accompanied by Olga Melasecchi the curator of the Jewish Museum in Rome visited Giulia at her home to speak with her about her mother’s life and artistic work.

Below is an edited version of the interview.

Cynthia Madansky: Your mother was born in Kovno Lithuania, can you speak about the Russian influence on her painting?

Giulia Mafai: I would say there is a Nordic influence, more than a specifically Russian one. Those who were born and live in northern countries, experience a type of shock arriving at the Mediterranean — It is the discovery of color, in their former landscape color is very soft, very gray and I have found as well as other critics that Raphaël’s paintings reflect her lifetime process of discoving color. For her, color was a reflection of life, strength, power. I recently read in Chagall’s diary the same emotion when he arrived to Nice, he was intoxicated by color. In my opinion color is about freedom, it is another side of the moon. For almost every great Russian painter, the great revolution is in the color. This is my idea, I am not an art critic though.

C.M. – Can you please describe your mothers daily rituals and practice as an artist, how it changed during the course of her life?

G.M. – First she was an artist, second she was a mother and sometimes a wife. Her day was dedicated to her art. Her family, she cultivated us like flowers. I have always respected her for this position especially as she was a woman from another generation, another culture. She was one of the women in history who went slightly out of bounds, out of the boundaries of good manners, and then were considered as rebels. So a woman in Italy, maybe in America was not like this, who in the ‘20s traveled alone and was able to speak, as many Russian friends, four languages –English, French, Yiddish, Russian and also a little Hebrew – must have been a phenomenon. They were the first women who paved the way for the next generations, they were the first to break these boundaries, to say that a woman is a person who creates culture.

C.M. – You lived during the war in Genoa, was your mother able to make any work during this time? Were there other Jewish artists in Genoa with her?

G.M. – No, there weren’t other artists with us, we fortunately left Rome, vanished without a trace. In 1938 because of the infamous racial laws my two sisters and I had to leave school and my mother along with Carlo Levi, Melli and Cagli – were forbidden to exhibit. Between 1938 and 1945 she worked but she couldn’t show her work. She had the strength to continue with her art during this tragic moment in time.

C.M. – Can you speak about the Cavour School and your mother’s influence on this art movement?

G.M. – The Cavour School was a very important influence on her life. When Raphaël arrived in Rome she was in contact with Mario Mafai and Bonichi (known as Scipione), and described Rome at that time as very provincial and stagnant. The Futurist movement of 1912 with Balla, Boccioni and others was once a revolutionary movement, but ended up falling into the arms of fascism. The artists in Rome were looking for different ways to express themselves. Mafai and Scipione looked towards museums trying to figure out painting. Raphaël arrives in Rome from Paris, a liberated cosmopolitan woman — in London she befriended Epstein and Zatkin, in Paris she became familiar with Matisse and Picasso’s painting — and met Mafai my father who she was with until the end of his life.

She told Mafai and others that Rome is not what you see in museums, that Rome is in the streets! The reds of Titian shift in the Roman sunsets; the greens of Veronese shift in the Roman cypresses, the blues. She was seeing Rome for the first time, and showed it to Mafai and Scipione helping them rediscover themselves. This is the important thing.

She recounts in her diary that she went to Mafai’s studio to see his paintings and she told him they were too sad. I believe that with the word “sad” for her at the time, who couldn’t speak Italian very well, meant that the paintings were too dark, lifeless, dead. Mafai got angry. He went out of the studio and bought a bunch of violets, brought them to her and said: “If you’re so good then paint!”. She began to paint, and the next day she showed him and Scipione a work that left them étonnant, speechless. They said to her: “Go on, keep painting!”

C.M. – Some of your mother’s work is clearly identifiable as Jewish subject matter, was there a clear reason why she chose this at moments in her artistic career and other times not?

G.M. – I believe that each of us is influenced by the stories, emotions that we experienced as children. We are like snails or turtles carrying our history. My mother came from a Jewish Orthodox family, the daughter and granddaughter of rabbis. My grandmother wore a wig.

For my mother this was inconceivable, religion never held an important place for her, but she treasured Jewish culture and tradition. The concept of escaping, fleeing is a repeating theme in Raphaël’s art which of course is related to the history of the Jewish people. My grandmother, Raphaël’s mother was a Sephardic Jew whose family fled Spain in 1492.

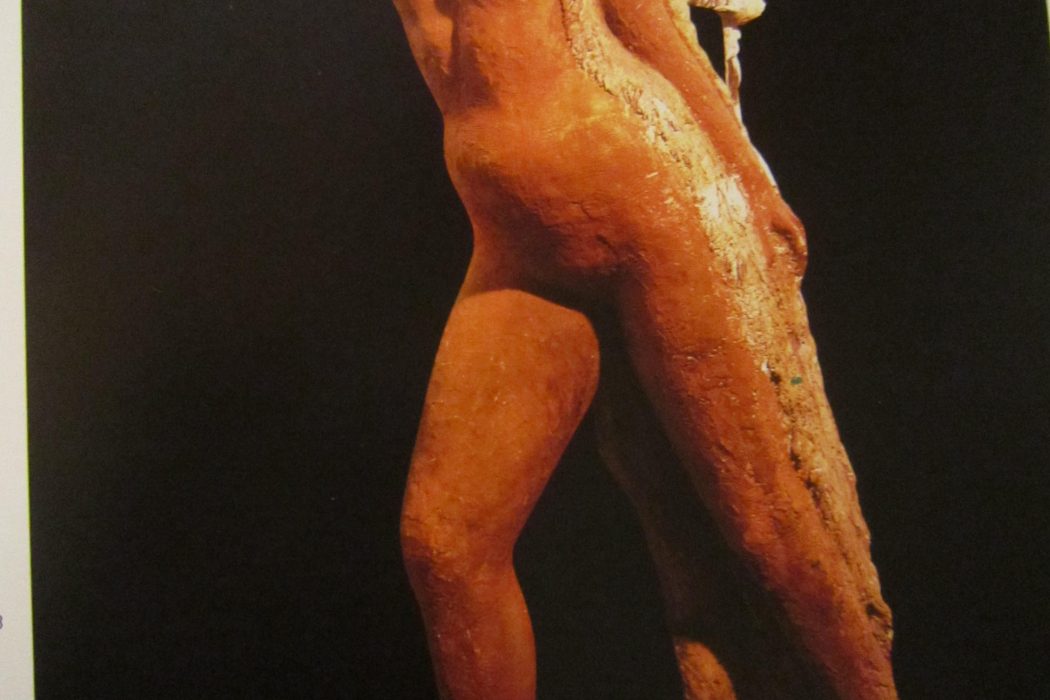

My mother made the sculpture “Escape from Sodom” in 1935, right before the war broke out in Europe. Because like most artists her “antennae” was very strong. The last “escape” sculpture that she created was during the 70s, “Escape from Vietnam”, a woman one leg in front of the other, with a child hanging on to her left leg, on her shoulders she carries another child with his tiny arms being almost a necklace on her front and the back of the mother’s head transforms into another head — a sculpture of a woman who is runinng away carrying three children. I have named her “The Womanly Tree” because these children do not just run away with her but they are her. They are her body transforming into a child. She flees with her flesh, on her legs. Women are the true strength of humanity, men make war and destroy, women go into the rubble to collect seeds and leftovers, they put the bricks together, light the fire and rebuild their lives.

C.M. – Your mother had many expositions and has been sometimes referred to as “Chagall’s sister”. How did she feel about this?

G.M. – My mother was a free spirit. She was “Chagall’s sister!” Also we were in Paris once and saw a major exhibition of Picasso at the Grand Palais. She was fascinated by Picasso’s total sense of freedom with materials. One of the last expositions she saw and that moved her was that of Jackson Pollock. An artist sees in another artist an opening to a new path, an inspiration to move forward in their own work. Not imitation, but an opening to a window which perhaps you haven’t even identified or seen.

C.M. – Can you please speak about her shift from painting to sculpture?

The transition was made…let’s say … mostly at an organizational level. In my opinion they are two souls of Raphaël. She was a strong woman, and sculpture was a constant struggle — it was something like Jacob’s Ladder, falling and climbing. She was never satisfied with her sculptures, she cut them, reassembled them, remade them. Painting was freedom, letting yourself go, poetry for poetry’s sake, pure joy. Sculpture is not joy; sculpture is drama, painting is like Chopin, the joy of putting a green near a blue, of discovering a red.

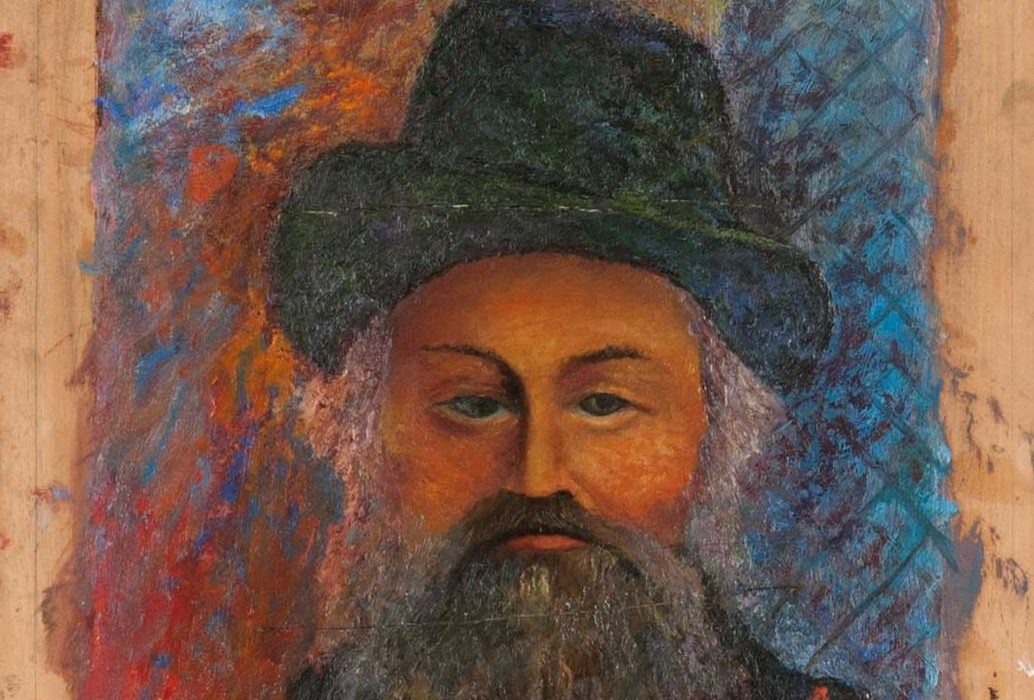

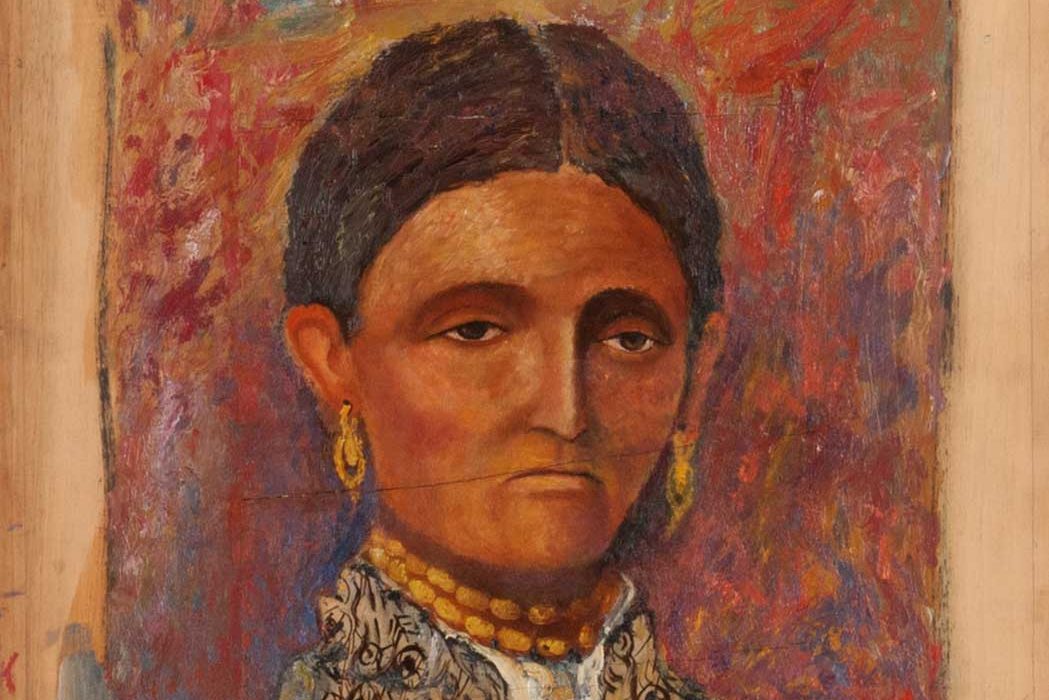

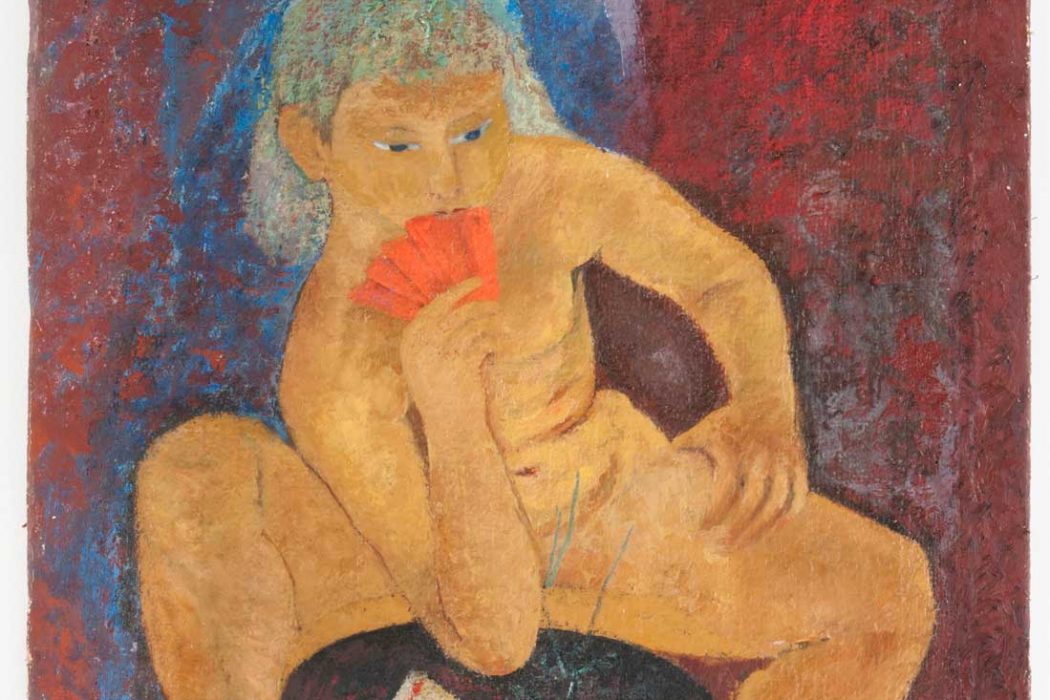

C.M.- Can you please speak about the portraits of her parents and “La Giocatrice”?

G.M. – They are two very different works made at different points in her life. The portraits of her parents were painted in 1928, “La Giocatrice” in 1950. Also the two themes are quite distinct, she painted the portraits of her parents, ten years, twenty years after their deaths almost as iconic tributes, — these are my ancestors, my roots. In “La Giocatrice” she is not a family member, but more of a symbolic representation of a woman exuding her sensuality, optimism, joy, strength.

C.M. – Can you please speak about the work of your mother in the last decade of her life, what influenced, inspired her?

G.M. – I’ll tell you that the last period of my mother’s life was a happy time. She finally built a house on lake Vico in the middle of the woods and she enjoyed her grandchildren. In Raphaël’s last paintings, this happiness, the children, dogs, cats, chickens kids, her joy of life was present. Also for the first time in her life she had the money to cast her statues in bronze. She divided her time between the foundry and her lake house where she painted. Her last period was only love.

C.M. – Lastly you opened the Centro Studi Mafai Raphael to honor your parents work, can you please tell me about the center?

G.M. – My two sisters and I recently established the Mafai Raphaël center. We wanted to create this center as a marker of their life work. Last year we held a beautiful exhibition of Mafai’s abstract works together with Jannis Kounellis. We are currently working on an exhibition of Raphaël’s drawings and prints made at the National Printing House. This center was created so that their artistic legacy would not disperse over time, so that their work may not be lost in history. We wanted to preserve a space for the works of Mafai and Raphaël.