At first glance and especially from a certain distance, Amelia Rosselli, reclining in her rocker on the front porch of the little house at 9 Clark Court in Larchmont, seemed like an elderly American woman – long ago retired. Very thin and bony, wearing a lightweight violet dress and rocking softly, she seemed suspended from time. Perhaps she pondered far away places or a childhood as distant as the moon. Nearing the veranda, you could see her snow-white hair, the stem of her neck swaddled in a black velvet ruff. Her well-lined face and fallen skin were lit by an inner pride. A kind of hidden force, it penetrated her eyes and seemed to have chiseled her pointed chin, making her appear forever on the verge of saying something unexpected and important, certainly not any old thing.

Turning from the sidewalk onto a little path of scattered stones through an unkempt meadow and heading toward the stairs that led to the porch, you would notice the white wooden columns that accentuated the ancient nobility of that crumbling and irreparably decadent house. Then, finally, you would see clearly the anonymous lady seemingly left on her rocker and forgotten there. Arriving at the end of the little path, once you placed your foot on the first stair, you would notice her long tapered fingers resting on the arms of the chair. The skin of her hands was pure ivory, and a diamond shone brightly on her left hand. Her seagreen eyes, shadowed by long white eyelashes, looked perpetually toward an indeterminate distance. But for whatever distant point upon which her gaze seemed to have been fixed, her eyes were nonetheless piercing and inquisitive – as if to ask the approaching stranger who he was and from whence he came. (But this was especially because her eyes were only apparently lost in reverie.)

From where, of what provenance? Despite a great deal of patience – which kept that lady lounging in her rocker – the where and the when were questions of the utmost importance. The quiet elegance of her costume and the iridescent flashes of her diamond made it seem as though she had fallen upon the veranda of that decrepit suburban dwelling – with its pathetic, fake neoclassical connotations – like a meteorite. That the “where” was Italy (a certain Italy evoked perhaps by cypresses or lemon trees, living rooms where one could still speak of certain things and in which “bending” had to do with exercise and not ethics) was understood thanks to a rigid simplicity which made it extremely difficult to imagine any other country.

But the “when” was shrouded in mystery. Her solemn countenance and posture could have been something out of the 19th century and, at the same time, any other period of time – centuries away or very recent. That there was something traumatic hidden beneath all this was evident in a silent pause – slightly longer than usual – and a certain reticence that was never less than polite.

But in all likelihood, the man advancing with cautious courtesy toward the stairs and offering his hand knew that the when coincided with a certain ill-fated date – June 9, 1937. That was the day the brutalized bodies of Carlo and Nello Rosselli were found in a ditch near Bagnoles-de-l’Orne – within a couple hundred meters of the splendid reddish and towering Castle of Coutèrne.

“Signora Amelia!”

“Dear Salvemini!”

From a handshake with both hands, their greeting resembled an embrace. The exclaimed simultaneously, “What a pleasure!” Salvemini who was short and stocky, laughed heartily exposing a large carousel of yellow teeth. A litany of “what a pleasure” -s followed. Meanwhile Signora Amelia, who was now sitting up straight, continued to inquire into her guest’s journey: “How was the train ride? I hope you didn’t have any stopovers … these trips, even if they aren’t so long can be very tiresome.” And Salvemini, enjoying a good laugh, “My dear woman, from Harvard, it’s hardly an arduous journey. I am not exactly a young man but I assure you that, for a 60-something, I’m still in pretty good shape.” The old man, whose words were accompanied by the vivacious gesticulations of his solid, peasant hands, was persuaded to sit on a padded little wicker chair.

From this modest porch, surrounded by other nearly identical cottages and yards, there came a buzzing of voices both deep and shrill that traveled over the garden and around the little plum tree in bloom. It was an island of diversity in that monotonous suburban landscape, squalid and full of petty neighbors in search of a way to best one another, either by painting their houses in a different color, or by displaying trinkets on tiny lawns already overrun by children and dogs.

In the humid afternoon, in which the blue sky loomed heavily, Salvemini went about describing his life at Harvard. As he spoke, a certain occasion came to mind (who knows how) when, many years earlier, he had met Nello for the first time. The memory intensified the pain of Signora Amelia’s grieving and, indirectly, it reminded him that his own life was strewn with corpses as well. And yet, it was this same senseless stream of death that inspired his stubborn desire to fight. There on the little wicker chair, in the presence of the delicate fluttering of Signora Amelia’s violet colored garments, he paused for what seemed like a long while before speaking. “In the Spring of 1920 – one of those Florentine spring days where the air is as transparent as crystal, such that one can make out the leaves on the olive trees all the way to Fiesole – a young artillery lieutenant came to see me”. He glanced furtively at Signora Amelia – her sunken blue eyes – to see if she guessed his thoughts. But evidently, at that moment, his thoughts were so fixed on a certain past, and certain nodes of suffering, that they could not be distinguished from those of his interlocutor – already immersed in that past and poised to travel with him to all its points of laceration.

Her tacit permission all but granted, he felt he might continue his inward digressions. “His name was Nello Rosselli and he was a university student. He planned to major in history and he wanted my advice. I knew his mother – a esteemed author – certainly by name but also a bit personally since we had a very good friend in common”. Signora Amelia’s gaze – so many years later – was the same slightly questioning, subtle and illuminating gaze that distinguished her in a Florence throbbing with intellectual life and esthetic experience, filled with serried exchanges in elegant bourgeois living rooms and dive bars alike.

Scanning her face however, one could detect the cruel marks of tragedy – the deep lines and wan complexion seemed strangely empty – as if polished by unbearable experiences. Salvemini turned his gaze away from her and inward again – back to Nello and to the sweetness of having such a pupil to shape and inform. He couldn’t help the bitterness that followed – the trauma which so brutally shattered his dreams of wisdom and intelligence – leaving behind only the mask of pain and suffering on his mother’s face.

His recollections continued, “Nello too had his woes, as they say in Naples. The first draft of Mazzini e Bakunin blew up in the storm of my critical commentary – especially with regard to the need for further research on some of the more obscure points. His second draft underwent a similar scrutiny. The third was already good enough to be his thesis. He swore that he wouldn’t let me read anything further for fear of doubling a work he considered complete – but he continued to work on it all the same, publishing it in 1927.”

But what was the point of continuing to remember? For him memory was essential to his work as an historian – otherwise going back in time was merely tantamount to suffering. Just as when his wife and five children were lost under the rubble of an earthquake and for two months he risked going mad, until he plunged headlong into work again. As an historian and as an historian of Southern Italy, his work was to remember and help others remember, but in actuality to forget, to reassure himself that absolutely nothing, nothing in his world and waking hours could bring him back to that bloody day in Messina in 1908. Not even Fascism – also a cruel and violent earthquake – would shake him to the core in such a way. He hated Fascism like the incarnation of evil and he waged a personal battle against the movement from its earliest days. Although he fought as an historian and a scholar, his intensity was such that he may as well have been engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the specter of evil in Italy.

He had been always been stubborn and was prepared to fight to the death against the Duce, his regime and the intolerably corrupt and subaltern Italy they represented.

In her characteristic quiet but solicitous tone, Signora Amelia continued to ask for news of his life at Harvard. She wanted to know about interesting encounters, how he got along with the students – in other words, all about the Harvard experience. Beyond the most obvious reasons for her interest, there lay the ingenuous curiosity of someone for whom – whatever the reality – America remained an immense, mysterious and marvelous place. “So, tell me how it’s going at Harvard?”

“It is an ideal place. I have many students, among whom there are a few passionate disciples. Five days a week I speak to them of the iniquities of Fascism, magnates and common people, Guelphs and Ghibellines. I teach them about Mazzini, Garibaldi, Cavour and even that rogue Giolitti who – after so many years of Fascism – doesn’t seem half as bad.”

Dressed in a gray suit with a loose fitting lightweight jacket, tall ankle boots visible among the folds of his pant legs, Salvemini leaned forward as if the growing joviality of his words were to correspond to the dynamism of his short torso and sturdy legs. The sweat on his brow and the hearty laughing that accompanied his words animated a face otherwise defined by a large jaw and ruddy cheeks. Meanwhile his eyes squinted to the extent that they appeared to be two fissures full of hidden hilarity – and yet they also contained flashes of pity and the stupor of someone who knows the devastation of this world.

Signora Amelia smiled too, her usual tight-lipped smile, but her eyes didn’t contain any of the joy that her interlocutor so wished to see. Maybe she was just tired, lately conversation, even with those nearby, was taxing – although she never lacked that air of courtesy and polite interest which encourages the person speaking to go on doing so. A less observant interlocutor might mistake her fatigue for absent- mindedness or inattention. But this was not the case – more likely, the bit of news or an observation had brought her back to something beyond the object of conversation and the events at hand. And absenting herself while continuing to bestow the light of her attentions upon the speaker, she would go back in time. She would re-visit one of those eternally gaping wounds – whose sweet horror had sown so many years of sorrow – and now existed only in these quiet ruminations. Leaning back again, the black ruff on the tendons of her long neck was conspicuously evocative of mourning.

Even while she made an effort to hang on the words of an exuberant Salvemini, she had somehow slid back in time – back to the pain of her first son’s death. Her adorable Aldo, the eldest of the three was heroically killed in action along the Pal Piccolo in the first days of WWI. The initial news of death had provoked disbelief and estrangement from the world.

And one night, some weeks or even a month later, a dream: the kind that are so atrociously sweet one is awakened by hope. “And one night in my sleep – the sleep of a night in May – I was awakened by the violent sounds of a door forced open. Unforgettable vision – even if seen with a child’s eyes. My brother, my older brother on the threshold of the front door: his hair blowing in the wind, his bright face almost hidden in the tri-colored pall, holding a goldtipped staff out in front of him. With all the windows suddenly open, the fresh, sweet air bursts in and a clamor of bells sounds in the distance.”

“Are you unwell, Signora Amelia? Can I do something for you?” Salvemini finally paused. The pallor of her gentle face suddenly seemed excessive, even haunted. He was concerned – maybe she suffered from the heat or a sudden loss in blood pressure. He was just about to get up when she stopped him in a polite but peremptory tone. “No need to worry, I am just fine. A little fatigued but what do you expect, at my age …” And he stood there for a moment – uncertain as for what to do and a little embarrassed – until he allowed himself to be seated again.

Now that they both succumbed to a slightly embarrassed silence, in the midst of those distinctly European memories, they suddenly heard the sounds of the American suburb surrounding them. Beyond the barking dogs and the constant squeals of the neighborhood children absorbed in their games, one could hear a lawn mower here and there, the chimes of an ice cream truck, car doors closing.

American noises that engulfed the air in an optimistic fervor, repeated thousands of times such that the overall effect was a strange and melodious fusion.

Professor Salvemini and Signora Amelia didn’t seem to hear any of the noises that surrounded them; they were submerged in the memory of a Europe to which they continued to belong with their whole selves. A Europe in which the political battles, the villas encircled by silver leafed olive trees, the suffering and the losses required their full and complete attention. All around them, “America” was a pleasant unreality and, at the same time, an irksome reminder of the great distance that separated them from the theater of actions and emotions past.

In short, they were in exile. Sitting on that inviting little veranda with its crumbling paint (brown from an earlier painting showed through the white on the rails), they had an incongruous air about them, almost conspiratorial. They continued ‘to manufacture words’, European style, words that wafted through the air in an effluvium of friendly rhetoric, long sentences filled with coordinates, exclamation points and parentheses.

The writing desk where Amelia managed her correspondence in the morning hours was a rustic little table, a rough-hewn shelf of sorts, the size of a first grader’s desk. It was nothing like the large table in via Giusti, inlaid and built on a series of gothic arches that joined the writing surface to the legs. A Victorianera piece, [Amelia’s former scriptorium] was both frivolous and austere – the very emblem of writing. Sitting in front of this grand piece of furniture on a ‘Savonarola- style’ chair (in its sober simplicity this chair was nonetheless inlaid with tiny diamonds of ivory), the younger Amelia wrote her first comedies in Venetian dialect – from El refolo [The Wind, 1910] to Il socio di papà [My Father’s Business Partner, 1911]. During those solemn hours – which neither children and domestic servants were permitted to interrupt – Amelia liked to wear a poet’s shirt with a stiff high collar. And from her clear eyes – already sunken and underlined by dark circles – there emanated a most vivid light and an almost obsessive intensity.

Derived from an impassioned and indefatigable moral awareness, that light remained in Amelia’s eyes, even in the little house in Larchmont. The hours spent at her small cluttered table saw letters produced and sent to dozens of Italian antifascists living across the U.S., in England and France. The letters she exchanged concerned events in Italy and in the world at large, the agony of Fascism, friends missing, and new political initiatives. For Amelia, who was already elderly and ill (spitting up blood and unable to keep weight on), these letters represented a web of relationships which – in their infinite ramifications – served to fill (in some way) the chasm left by her personal losses. Through these letters, she participated in the political work of that tumultuous era. And, at the same time, she found a way to keep her tired heart beating.

She wrote in a firm but generous hand and her penmanship was perfectly legible although perhaps more appropriate to romantic sentiments (had she been of the age) than to politics. She had learnt to write in that wonderful 19th century style and she enjoyed the aesthetic operation in the formation of her words and characters; her self-satisfaction was visible in the roundness of the vowels and the stiff verticality of the consonants. In addition to visiting – which was not always possible – Salvemini wrote to Amelia often. Long letters in which he expressed his doubts and concerns with regard to what effect U.S.-based antifascist activities could have on the future of Italy. Once light-hearted and enthusiastic and then, at times, equally discouraged, Salvemini’s prose was filled with the outpourings of a person who – in spite of his age – had never lost the candid and honest approach to things that children have. Indeed he seemed entirely immune to the diplomatic mediations and compromises that seem so necessary for political relationships – including those among anti-fascists.

At Harvard, in his little apartment near Lowell House, he taught his classes with the same drive and enthusiasm he had had while still a young unknown professor at the University of Palermo in the first years of the 20th century. His approach was the same – to throw the naked and brutal truth in his stunned students faces. (The latter, so accustomed to the ‘politically correct’, bureaucratic administration of information and ideas, were always impressed.)

Even now that he was old, nothing had really changed. He always went to bed early – never after 10PM – and by 6 am, he was already up and ready to go. Before going out to teach, he sat at his desk, piled high with books and pamphlets and besieged by immeasurable piles of documents on the floor.

There he assailed the pages of his correspondence, a near physical rage distorting his characters and rendering them almost indecipherable.

As he spoke to his American students in strongly accented English, he often confused their freckled faces and stringy hair with those of other students from his past.

As he spoke to his American students with his strong Sicilian accent, in the middle of some polemic on historical facts, he often confused those fair faces, with freckles and stringy hair, in a fog from which there emerged the classroom from Piazza San Marco in Florence, in those years of growing Fascist violence, before the beatings and his exile that seemed to never end. Just as now when he railed against the barbarization of Italy, back then similar bourgeois faces danced before him – young men and women who soon after would have chosen to be on one side or the other of the [political] barricade being erected.

Then having placated his exasperating desire for those facts to penetrate the innocence or indifference of his students, he would go for long walks around the campus. Vast meadows broken up by sycamores, elm trees, blooming shrubs, imposing Neo-gothic buildings and swarms of students laying about in the grass: the place had the misleading and even insidious air of a perpetual vacation.

Dressed like a European with his vest and watch chain, Salvemini moved forward on his short legs apparently aided by a Malacca cane with a silver knob. In actuality, he mostly held the walking stick out in front of him, using it to feel around the terrain and moving it left and right to the rhythm of an animated imaginary dialogue with himself. He seemed to anticipate an ambush – as if that idyllic landscape concealed polemical adversaries ready to pounce at any moment.

Sometimes two or three of his students accompanied him. Since they were both intimidated by and in awe of his passionate bursts of energy, they followed cautiously, careful to remain a couple steps behind him.

Seated at her desk and wielding a silver and ivory paperknife, Amelia opened Salvemini’s letter hastily as soon as it arrived. The date read July 28, 1943.

“Oh how I understand you my dear Amelia. I’ve been turning your sentences over in my mind for days. Rejoice in Mussolini’s fall? It is impossible for me – all I can think about are the countless innocent men, women and children and the bombardments that reduced them to a pulp so that this man could be deposed. Meanwhile his accomplices and all their accomplices are still at large.”

“When in 1918 the peace treaty was signed, I wasn’t able to rejoice. I didn’t know how. I saw the abyss our politicians and leaders were digging in our midst. Rather than rejoice, I spent several days in despair. I feel the same way now. Condemned by the Anglo-Saxon court (which is responsible for some of the most ferocious crimes ever committed in God’s name), I predict an atrocious criminal treatment for Italy. I cannot discern any light or hope around us. Now that I have seen the demise of that man, I would like to die myself. I am 70 years old – what do I have to live for at this point? If I could separate myself from the reality of today, if I could not read the newspapers – I would dedicate a few years to revising a few of my most worthy books. But even this hope has been dashed.

The books will never be finished because I have to write articles and I end up giving vent to ideas that assail me in a storm so violent that I fear I will go mad if I do not write them down.

But it is ridiculous to think of oneself when the whole world is suffering even more. Tiriamo innanzi!

Tomorrow I shall send you the final version of my pamphlet on Carlo e Nello [Carlo and Nello]. If you would be so kind as to translate the text into Italian, I think we should have it ready to launch in Italy as soon as possible.

Might I ask you to translate a small volume on the Tribunale Speciale [Special Tribunal] – in defense of the State? And also a book I am writing on Fascism, 1929-1943, which should be ready by the end of August.

We need to get all these things on the Italian market sooner rather than later. It is the only way to enlighten the minds of our young people who don’t know anything about what has come to pass. Perhaps all this hard work and labor will save us by helping us to forget and by keeping us from thinking too much.

Yours with great affection, Gaetano Salvemini”

After having read the letter, Amelia remained seated in silence for a long time. She was contemplating Salvemini’s words, “I would like to die”. It was unsettling, especially because she had always thought of her friend as the incarnation of vitality, the essence of the fighting spirit, and it was difficult to imagine him so dejected. And yet she’d had the same desire for many years. In spite of a growing number of grandchildren, her beloved daughters-in-law Maria and Marion, a compulsion to provide all her visitors with encouraging and optimistic words, and the many encouraging words she wrote to others on a daily basis – she couldn’t help wishing for death.

But her wish was strangely peaceful and devoid of anguish. In fact, the death she imagined and desired was not a violent and mysterious cessation of life but rather, a tiptoeing quietly away from the stage at the end of a terribly magnificent and sumptuous show. By going away quietly in this manner, she might avoid any further suffering – especially given that, deep within and unbeknownst to herself, she had already renounced the essential ties to existence. In 1916 she had gone to visit the mountain cemetery where her eldest son Aldo was buried. Killed in action, his death had earned him a silver star.

A year or two later, she had written the short book Fratelli minori [Younger Brothers] such that Carlo and Nello (and younger brothers all over the world) might better understand the bitterness associated with the apparently senseless death of their older brother. “The little cemetery looked like a nest overlaid with rocks.

There were so many little birds in there – all sleeping with their heads under a wing.” This language, so consonant with her pain, over years that followed, seemed to have been deprived of its adequacy and relevance. It was as if, with each new wound, she lost the meaning and the key to the earlier one and she was forever sinking deeper into an unfathomable abyss of grief.

In this way the years had passed, broken up by a succession of losses, overwhelming her ability to write about them. The only remaining signs were in her deep sunken blue eyes and the lines on a face that was ever more diaphanous. Pale and transparent, her eyes were like those of a child traumatized by too many tragic events that no one had wanted to explain.

Now that a man as tenacious and vital as her friend Salvemini harbored a similarly poisonous desire, she felt less ashamed of herself. After having remained immobile for some time, she took up her pen and wrote a long letter in response. In a corner of the window in her bedroom, she could see the side of the house next door. The remaining space was filled with a hedge – ravaged by dogs and children’s toys –, a few Sycamores and the blooming plum tree.

Amidst the green of the trees and grass, the white siding of the house next door and the glass of its windows glimmered in the dancing sunlight. Writing to her children’s teacher, Amelia was influenced by the reality which shone through her window. In this way, despite the wish she shared with her friend, she was reminded of her seven young grandchildren – including Nello and Maria’s four children who lived with her – and she felt a sudden surge of joy. Just making sure that they didn’t forget the Italian language or the manners of which their American schoolmates seemed so terribly ignorant, was nearly a full time job in and of itself.

Those wild children running around, turning the house upside down with all their scuffles and games, was a welcome distraction from the constant pull of Europe on her thoughts. Without all the commotion, her thoughts would be fixed on Italy, on the empty places at the table. And she would think especially of Carlo and Nello’s exuberance and their interminable conversations in search of the facts, of truth, or just to keep joy alive and to safeguard the possibility of laughter.

She found herself writing to Salvemini about her home life, her grandchildren’s different characters, the things she read to them – from Pascoli or Carducci –, the music she shared with them – Toscanini’s version of Beethoven’s symphonies -, and even the trouble she had in putting them to bed. Then, realizing that her friend might not be interested in all these details, she asked him about Allied politics, the war and the infighting among Italian anti-fascists in New York.

Many weeks passed. The war continued to go back and forth but more and more it seemed that the Allies were gaining strength. Nazi-Fascism, despite a few scattered victories, was largely on the defensive. One day the war would end.

Then another letter arrived from Salvemini, with the usual Lowell House stamp, dated December 31, 1943. “My dear Amelia, I read and re-read your letter with tears in my eyes! So many memories, so many catastrophes, so many loved ones lost forever! What happened to Ernesto Rossi? What of Nello Traquandi? And Ferruccio Parri? If only we could know what they think of things! As it is, I am limited to fragmentary pieces of news, carefully monitored by the censors, and I am reduced to guessing, to launching hypotheses into the void – too little and too painful for any man made of flesh and blood and not iron.

And yet, it’s useless to harbor illusions. The unity that once existed among our anti-fascists – when there was no hope for salvation – is gone forever. We have a right wing that ignores the

Italian people or, at least finds them entirely incapable, and looks to the British and the Americans for everything. By the same token, they are ready to accept whatever (and however little) the Allies are willing to do for a ruling body in Italy.

Even as they feebly acknowledge the hope that they will rid us of the king and his son, they will be satisfied with anything that eliminates the Constituent Assembly and any danger of a republic. There is an armistice agreement that doesn’t have the slightest intention of being administered by a prime minister or president and it refuses to cooperate with the parties responsible for the present disasters.

Moreover the conservatives want to destroy all that our friends have worked for in Italy, preferring to tag along behind the king and his generals. Rather, they prefer to wait out the day when the latter will be fully dishonored by their compromises.

“I have made my choice. And I intend to fight the battle here, because it is here that Italy’s fate will be decided. The last word shall be Roosevelt’s. If there is any hope of obtaining something good for Italy, we’ll have to extract it from Roosevelt (who is of course dependant upon public opinion here). But it will be like attacking a slope of the Himalayas with a toothpick. Anyway, “tiriamo innanzi”. We have no choice but to remain loyal to the memory of all our dead – thirty years of dead people – from 1915 to today. How many we have lost!”

“Dear Amelia, I don’t know what to wish for you in 1944. As for me, I wish for death because I shudder when I think about how they are certain to botch the peace treaties. (Especially after all the incompetence that went into to bringing this war about and then losing it…) “I bid you adieu until late January. A warm embrace to you and dear Maria too, Gaetano Salvemini”

In spite of the fact that Amelia and Salvemini exchanged letters regularly, the real dialogue between them was derived from the hours they spent together on her front porch. (They visited a few times a year, whenever Salvemini’s schedule allowed.) Of course their memories were of the house in Via Giusti in Florence or Villa Apparita in the hills, of promenades among the cypresses and meetings with Carlo and Nello in Piazza San Marco. Theirs were memories of a vast and expanding world, propped up by vague but eloquent hopes. And if the hard facts of Fascism’s victory had limited them and even rendered them absurd, their dreams of a better world had nonetheless provided brief flashes of intense happiness. But the present – personified in the sagging veranda and the indifference of a surrounding world which could neither understand nor partake of their memories and suffering – existed only in these brief colloquia. Italy came alive in the stories, information and ideas they shared. It was a world they intended to defend even if only by the fact of their own survival – their growing old, notwithstanding an uncertain future, hostile events, and in spite of the suffocating banality of the American suburbs so filled with meaningless politeness and artificial smiles.

They were immersed in what seemed like an eternal twilight – or was it simply the smog emanating from the area around that vast but, at times, stagnant body of water between Westchester County and Long Island? The pain that had permanently torn their worlds asunder lurked beneath all their discussions of family and politics. For Salvemini, it was the day of the 1908 earthquake in Messina. In 1909, not even a year later, he had written to Giovanni Gentile:

“I am moving forward: I work, give papers and speeches, organize conferences and I raise my voice against those who seem dishonest or insincere. And people think I’m strong because I do, however mechanically, whatever I did before. In actuality, I am a poor disgrace of a man, without a home or even a roof over his head, who saw eleven years of happiness destroyed in two minutes. I keep a few letters from my wife, my sister and the children in my desk. I can only read a couple at a time because I am soon overcome with such desperate sobbing that I want to die.”

Sitting in silence, they continued to write one another. Letters that were sent – mailed in haste even, when one was concerned for the other or his or her relatives. Out of desperation and in the darkest hours: after the flight from Lipari, when Nello was imprisoned, when Carlo was wounded at Mt. Pelato. Salvemini, whose discomfort in the chair was beginning to show, asked Amelia if he might remove his shoes. She nodded in agreement. When he bent over all you could see was his rounded baldness and receding shoulders. He puffed and grunted as he untied the laces. “I’m sorry Amelia, I’m getting old and everything is becoming an effort.

Only my head works; who knows for how much longer,” he muttered pointing to his head. The conversation went on; they spoke of friends lost between the States and Italy, almost as if they thought that – in mentioning their names – they might be able to save the missing from the abyss into which Fascism and the war had plunged them. Every once in while, they were reassured by some news regarding the hiding place of a beloved comrade in arms. But no sooner had they sighed in relief than they would begin worry how long he or she might be safe. Thus united in apprehension and hope, they proceeded with their melancholy cataloguing – like a grand party in the early part of the century where the guests were announced as they arrived.

For them, everything had already been, and yet, the continued to invoke the future. In fact, the future was all around them even as they spoke. But perhaps there was a kind of squabble between two different futures. Maybe the road lined with identical houses on either side – where tired people returned from work in the evenings – was different from the one defined by Giustizia e Libertà – or, equality, progress, tolerance.1 Yet hope lingered in them as if they were certain that the future contained a global blessing, uniting us all – from the Italy they so loved to the rest of the world, including that little suburb a few dozen miles from New York City – under its beneficent cloak. Yes, the future would touch even Clark Court, a dusty little dead end with all its silly postage stamp lots and yellowed grass.

Maybe in naming and portioning out that future world, Salvemini and Amelia were actually recalling the past. This world, now vanished forever, was nonetheless etched fervently into their hearts. It was a world of the dead, ruled by the same laws, but so much so that all their speaking of the future was still valid and relevant. Neither would have accepted the notion that they imagined a “beyond” or anything in the least bit transcendent. They were possessed of that certainty storytellers have and utterly convinced that those they had lost were somehow contemporaries. Everything from their desires to their gestures and actions served to confirm this belief. There was nothing morbid in their pastime and the thought that their dear ones were eating, taking a walk, or working on a book in the library, was full of the sweet presence that is found only in concrete reality. A presence that is continually re-incarnated and constantly evolving – speaking, smiling, getting into arguments.

And at the same time, all this evocation of the past and the dead allowed the two to remain suspended from time. Captured in that illusion, the professor with the little white beard and the elderly woman with diaphanous skin seemed to be protected from the corruption that obscures the material world. To be sure – they were aging and infirm and isolated by the ingenuousness that kept them engaged in that network of emotions and relationships.

However, at the same time, their naivety and candor also scattered them around the world in all the places they chatted about – from Tuscany to Apulia, certain thermal baths, islands of exile, Paris and Dobbiaco. In this way, their youthful hearts continued the voyages they had undertaken so long ago.

In their minds, they were wearing hiking boots and woolen socks and walking along side the rushing stream that cut through the meadows surrounding Dobbiaco. Or sweltering in the hot sun as they made their way to Carlo’s place in Lipari. Or laboring over documents in the religious silence of the British Museum, or sitting in a café with disciples and compatriots in Molfetta …

Landscapes and houses were exceptionally vivid and even the most minute details came across clearly. And yet however luminous, the light of their memories was also mysteriously indistinct such that the shadows produced by a setting sun merged with those cast by a moon firmly planted in the night sky.

Only the crumbling veranda remained the same. The creaking stairs, the wobbly railing, the little columns that recalled an old theater set, attached to an anonymous suburban house, provided the backdrop for the whispering voices of the dead. In a bird’s eye view of that scene, there would be a multiplicity of identical front porches and the gesticulating professor and the pale-faced elderly woman might have been two retirees engaged in a neighborly chitchat or an old married couple absorbed in a world of memories. In that apparently sleepy suburb, they were barely noticeable, merely a splotch of color – the black of Salvemini’s double-breasted blazer and the violet of Amelia’s dress.

They might also have been any two immigrants – common enough in those days – speaking excitedly (maybe in Yiddish or German) and gesticulating wildly in passionate recollection of a long succession of misfortunes and tragedies.

Notes

1. Giustizia e Libertà, literally “Justice and Liberty” was the name of the anti-fascist political party to which both Amelia Rosselli and Gaetano Salvemini belonged. In the original text, the words carry both the party connotation and the literal meanings.

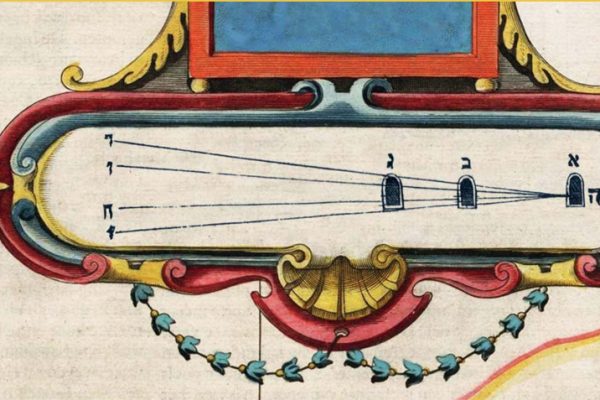

Image: the children of Nello and Carlo Rosselli, France, 1938 ca.