How Special Collections archival holdings tell the story of our time

The Max Ascoli Archive

Archivio del Senato

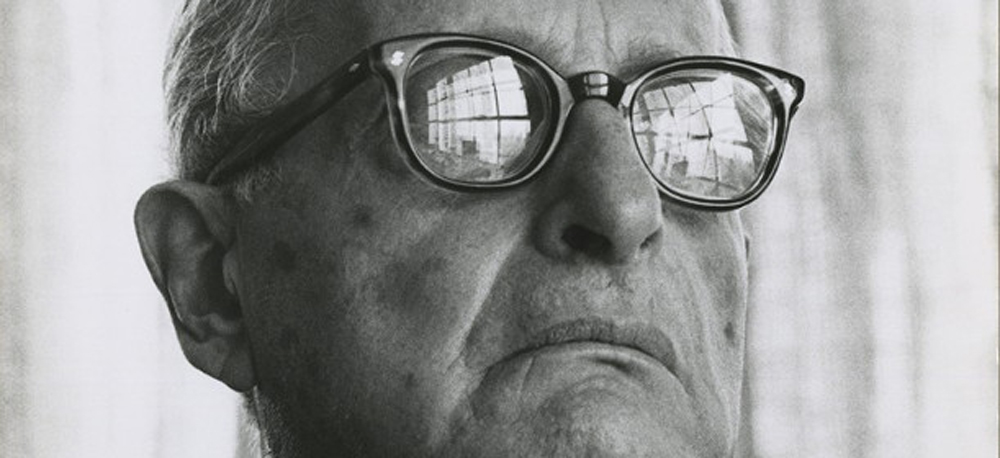

Max Ascoli (1898-1978) created The Reporter in 1949, a magazine that became a leading voice for liberalism in America for the next 20 years. Special Collections contains the editorial files of the widely respected journal among its many historical treasures.

Ascoli was born into a Jewish family in the northern Italian city of Ferrara, which he later referred to as the “cradle of Fascism.” Trained in political philosophy and law, he did not practice much law but instead taught in Italian law schools. In 1928, he was arrested after his name was found in the address book of another intellectual charged with carrying on clandestine political activities. With his university career in Italy over, Ascoli immigrated to the United States in 1931 after the offer of a fellowship from the Rockefeller Foundation.

In an essay entitled “Max Ascoli: A Life Remembered,” Rosario Tosiello (CAS’63, GRS’64, GRS’71), a professor of history at Pine Manor College, writes, “In correspondence with a fellow exile of Italy, Ascoli observed that there were two currents among Italians in America: those exiles (esuli) who did not intend to become Americans and who live like pilgrims (pellegrini) in expectation of returning to Italy, and those American citizens of Italian origin, including himself, who did not think about returning to Italy.”

In the United States, Ascoli became involved in the efforts to rescue scholars from the ravages of European fascism — especially those Italian scholars who had been kicked out of Fascist Italy. His rescue work solidified his growing role as one of America’s leading anti-Fascist spokesmen. In 1949, Ascoli started publishing The Reporter. The journal of liberal opinion, which Ascoli said he wanted to create to appeal to a large section of “the intelligent adult reading audience, far beyond the little ghettos of professional liberals clustered around the so-called journals of opinion,” represented his greatest success.

“The Reporter became the leading voice for liberalism and political thinking,” writes Tosiello. “Its issues and ideas reached into the highest levels of government as well as the intellectual and general reading public. Every president from Truman to Nixon received Ascoli himself.” Over time, however, The Reporter alienated many of its liberal readers, perhaps reflecting Ascoli’s disenchantment with public developments. He opposed student demonstrations and the growing opposition to America’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

When Lyndon Johnson announced in 1968 that he would not seek reelection to the presidency, Ascoli closed down The Reporter. “There were, however, other factors,” asserts Tosiello — “a declining readership, the continuing unprofitability of the magazine, and Ascoli’s health and age.” Despite its ending, The Reporter helped shape American intellectual thinking. Ascoli’s contributions, writes Tosiello, “both intellectual and practical, are testimony to his importance as a thinker, an Italian, and an American.”