The New York tribute to Nurith Aviv opens with Translating, the last film of a trilogy that began with From One Language to Another and continued with Sacred Language, Spoken Language. Through an exploration of Hebrew, its transformations, and its relation to history and other languages, Aviv digs into the magical construction of language, its written and oral forms, its limitations, and the human ability to trick them. The trilogy fully unfolds when illuminated by a fourth film dedicated to the Ivorian artist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré and his invented syllabary of 448-letter containing the oral tradition of the Bété people.

For centuries, Hebrew was the language of Scripture, liturgy, and rabbinic commentaries. Then, by force of national and political will, it was reborn as a language of daily life in the early 20th century. In Nurith Aviv’s films, writers and artists explore their intimate, often conflicted relationship with Hebrew’s layered past, reflecting on what has been forgotten or repressed and what needs to resurface. Their confessions overlap and part, as the film allows no single version of this history to prevail.

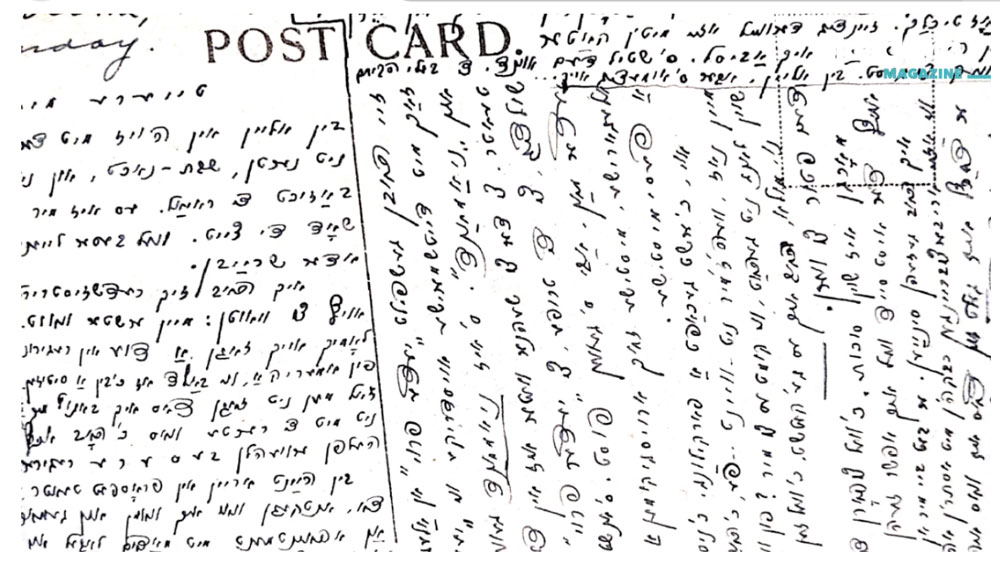

“The people Nurith Aviv invites to speak in her films speak several languages” writes Hélène Cixous. “Like the filmmaker, they live between languages. They are exiled Jews who became Israeli citizens and had to unlearn their first languages to acquire Hebrew; they are Palestinians who speak between Arabic and Hebrew. They are Deaf people who are forced to vocalize and who, in private, express themselves in sign language, even if it means inventing their sign language – Tiphaine Samoyault notes on this subject that Signer “is a film about the birth of languages”. They are translators of Hebrew, Italian, German, and French, they are translators of Yiddish scattered throughout the world, Jewish or not, who adopt it as a language and give it back voice, accents, breath, and life. And these spoken languages, whether adopted, translated, signed, or imposed, are themselves plural. Even the pronunciation of a letter is plural.”

The following excerpt from Jacques Mandelbaum’s review in Le Monde gives us an entryway into Nurith’s poetic and epistemological journey: “One of the major interests of the first two films was to remind us how much language, and therefore the people who speak it, are shaped by strangeness, open to influences; […] In Traduire Nurith Aviv takes a world tour of Hebrew translators, modest titans who attempt to move towards other horizons for this historically, theologically, and politically charged language.

More than two millennia after the first attempt at this (the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Bible by Alexandrian Jews), the challenge remains daunting.

Surprising and fascinating remarks emerge throughout a sequence of conversations, filmed with beautiful restraint. In Barcelona, Manuel Forcano, translator of the poet Yehuda Amichaï (1924-2000) into Catalan, acknowledges the influence of the renovator of Israeli literature on his own poetry. In Acre, Ala Hlehel, translator of Palestinian origin of the playwright Hanoch Levin (1943-1999) into Arabic, explains how he must proceed “to the murder of the father language” to bring the conciseness of Hebrew into the efflorescence of classical Arabic.