Marina Calloni is a professor of social and political philosophy at Università Milano-Bicocca, in Milan. She has been a research fellow at the University of Frankfurt, working with Jürgen Habermas, and senior researcher at the Gender Institute of the London School of Economics and Political Science in London. Since 2007 she has been a member of the Inter-ministerial Committee for Human Rights (CIDU), at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Rome. She is Director of the International Network for Research on Gender and Empowerment and cofounder member of the “European Platform of Women Scientists” and of the “Unesco Network of Women Philosophers”. Her publications include: Politica e affetti Familiari. Lettere dei Rosselli ai Ferrero (1917-1943), Marina Calloni and Lorella Cedroni Ed., Milano: Feltrinelli, 1997; Amelia Rosselli Memorie, Marina Calloni Ed., Bologna: Il Mulino 2001; M.Calloni (ed.). Violenza senza legge. Genocidi e crimini di guerra nell’età globale, Torino: UTET, 2006; Calloni, (ed), Women Immigrants as constructers of a New Europe. Gender Experiences and Perspectives in European Trans-regions, Helsinki: Kikimora, 2010, M. Calloni & E. Hunt Botting (eds.), Borders, Sovereignty, Rights, Border Crossing Seminar 1, Milano: University of Milano-Bicocca, 2014; A. Saarinen & M. Calloni (eds.), Builders of a “New Europe”. Women Migrants from the Eastern Transregions, Helsinki: Kikimora, 2012; J. Szapor, M. Hametz, A. Petö, M. Calloni (eds.),Tradition Unchained. Central European Jewish Intellectual Women from the Late Nineteenth Century, Edwin Mellen Press, New York, 2012; Y.Galligan, S.Clavero, M.Calloni, Gender Politics and Democracy in Post-socialist Europe, Opladen: Budrich, 2008

A new enlarged edition of Gaetano Salvemini’s Carlo and Nello Rosselli, A memoir, curated by Marina Calloni, to be published by CPL Editions and Viella Edizioni.

Beyond the impulse to commemorate and pay homage to the Rosselli brothers on the 80th anniversary of their murder, this new publication aims at bringing attention to the bearing of Carlo and Nello Rosselli’s experiences on today’s political and civic disengagement.

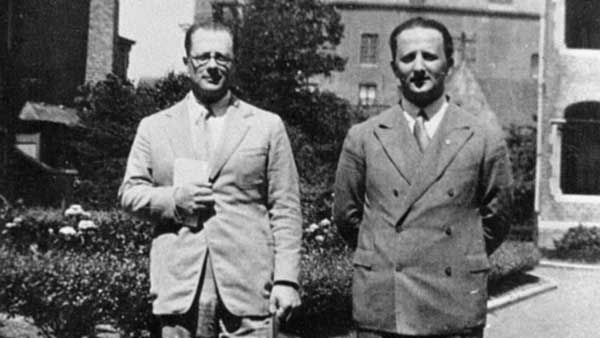

The Rosselli’s political passion, which they expressed in thought and action, constitutes a lasting example of active resistance to totalitarianism. Mussolini’s wrath against the Rosselli brothers is an implicit recognition of their role as leaders, inspiration, and point of reference for the opposition to the regime.

Despite the efforts by scholars, the ethical/political trajectory of the Rosselli brothers— from Nello’s studies on the Risorgimento to Carlo’s critique of Marxism and call for a liberal reformulation of Socialism— deserves closer examination, particularly on this side of the Atlantic. In a letter to Salvemini, Carlo Rosselli had expressed his wish to provide “a moral example to future generation”, this book attempts to be a step toward the realization of that desire.

Alessandro Cassin: Over a year ago, you suggested marking the 80 anniversary with a reissue of a short book by Gaetano Salvemini Carlo and Nello Rosselli. A Memoir, almost an instant book, written in the immediate aftermath of the murder, in 1937. You proposed an enlarged edition that would supply context to the history of the various additions and translations of this text, as well as some of the correspondence between Amelia Rosselli (Carlo and Nello’s mother) and Gaetano Salvemini. What is the relevance of this book today?

Marina Calloni: Unfortunately, still today, the perception of the Rossellis’ legacy remains limitedly confined to their anti-Fascist activity, overshadowing Carlo’s theory of Liberal Socialism, Nello’s work as a historian of the Risorgimento, and Amelia’s many intellectual achievements. More in general, the family’s place in the Italian political and intellectual history remains underappreciated. The choice to publish a new and expanded edition of Salvemini’s memoir is in part an attempt to re-examine the dynamics within the family and its ties to Gaetano Salvemini.

AC: Salvemini had been, at different times, a mentor, a political comrade and a close friend of the Rosselli brothers. He later became a strenuous advocate of their legacy, while all along maintaining a very strong bond with their mother. Can you retrace briefly some of the key moments in their interaction?

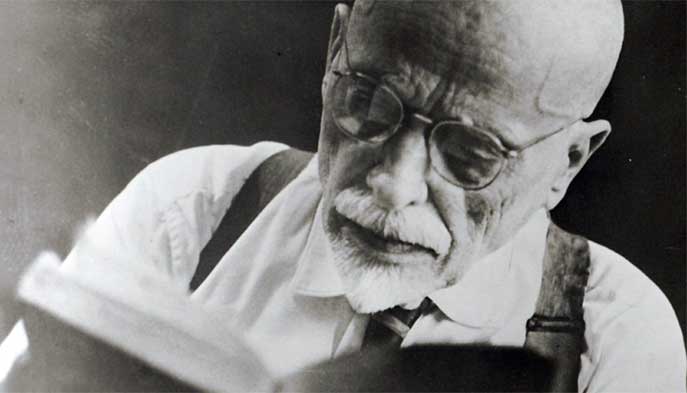

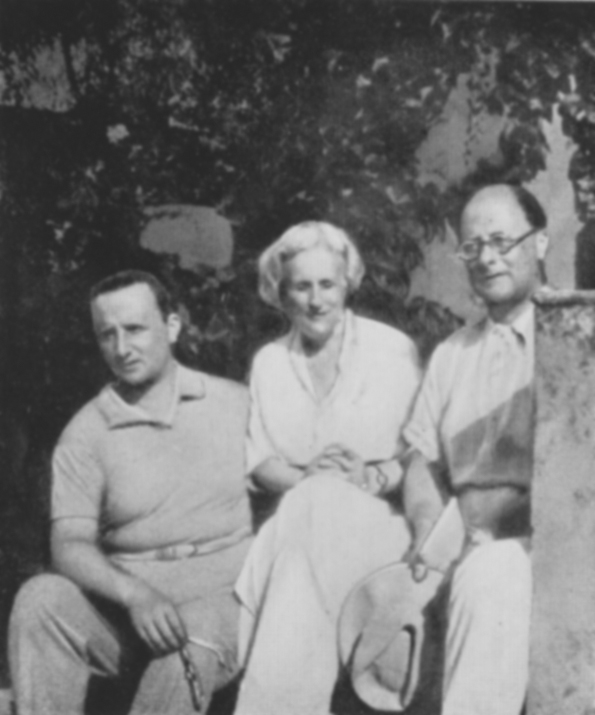

MC: Salvemini and Amelia Rosselli, née Amelia Pincherle Moravia, met in the 1910s when Amelia was a renowned writer for the theater and Gaetano a famous professor of modern history. They were both democratic interventionists, that is, supporters of the Italian war against Austria. Salvemini was first introduced to Nello as “Amelia’s son”, around 1919, when Nello was a university student. Salvemini soon became Nello’s mentor and proposed to him a thesis on Giuseppe Mazzini and the worker’s movement of that time. Their mutual admiration and friendship rapidly expanded to include Nello’s brother Carlo. I would say that the bond was formed around shared cultural interest and early opposition to Fascism. Before being forced out of the university in 1925, Salvemini participated with the Rosselli brothers and others in the founding of the first antifascist paper, Non Mollare! (Don’t give up!), which was soon suppressed by the fascist police. Salvemini maintained a strong relationship with the Rossellis, not only the two brothers but also their mother Amelia, and their respective wives, Marion Cave and Maria Todesco. This relationship continued during the years of their exile (1937-1946), first in France, then Switzerland, England and finally in the United States. Salvemini himself had left Italy in 1925, and lived in exile in France, England, and the United States, returning to Florence in 1949. In the US, Salvemini was first appointed Lauro de Bosis Lecturer and later Professor of the History of Italian Civilization at Harvard. In addition to the well-known correspondence between Salvemini and the two brothers, there are a number of letters between Amelia Rosselli and Salvemini which attest to a profound and uninterrupted friendship and exchange that lasted about 40 years, until Amelia’s death in 1954.

AC: Some of these letters relate directly to your book…

MC: Indeed. And some will be included in the new edition as evidence of Amelia’s essential role in the writing of Salvemini’s text. I would venture to suggest, that the book should be seen as practically co-written by Amelia.

AC: What do you think was her role?

MC: Today you would call her a ghostwriter! Their letters show how much Salvemini relied on Amelia for the early biographical parts of the book. In addition, it was Amelia who insisted on including explicit references to Aldo, her first son, who had died as a volunteer in World War I, and according to her, continued to inspire Carlo and Nello’s lives. Of course, as their mother, she was a primary source, yet I would argue that she was certainly more than a consultant on the book.

AC: Where was Amelia, when Salvemini began to write the book?

MC: Amelia was in Paris for the funeral of her sons on June 19th, 1937 but chose not to attend the ceremony, which attracted a crowd of 150,000 people. After that, she decided not to go back to Italy because of the dictatorship: as she wrote in a biographical note, hers was “a voluntary exile”. From Paris, she moved to Switzerland where she was joined by Maria Todesco (Nello’s wife) and her four children. All along she was epistolary contact with Salvemini, and her letters, from the mountains and from a thermal resort, show her active participation in the conception and writing of the book. Particularly the first chapters, which trace the family’s history, were taken by Salvemini directly from Amelia’s letters.

Salvemini had been a regular frequenter of Amelia’s lively literary salon in Florence since the 1910’s and grew to trust her intellectual and political acumen.

They were near contemporaries, Amelia Rosselli was born in 1870 while Gaetano Salvemini in 1873, and their friendship, based on shared ideals, grew over the years, in exile. They were both active members of the Mazzini Society, often sharing minority opinions such as their opposition, after the war, to the idea of a popular referendum between monarchy and democracy. Rosselli and Salvemini believed that the monarchy should not have had a further chance.

Salvemini (who lived in Boston) was a frequent guest at the Rosselli’s home in Larchmont, New York. They met again often in Florence in the late 1940s, after their return from the American exile. They died at the same age of 84: Amelia in Florence in 1954 and Salvemini in Sorrento in 1957.

AC: Salvemini’s Carlo and Nello Rosselli. A Memoir has had a complex editorial history, could you summarize it and describe the content of the new edition?

MC: The text was first published in London in 1937 by For Intellectual Liberty, as the first volume of a “Carlo and Nello Rosselli Series” which was meant to include “works of history, political science, memoirs and works of imagination” to be published in French and Italian. The slim volume was prefaced by an In Memoriam by Ernest Barker, a professor of Political Science at the University of Cambridge. It comprised nine chapters leading up to the assassination, followed by a short text by C. Bouglé, director of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, in Paris, entitled On the Grave of a Hero. It also included photographs of Carlo and Nello individually and with their mother, of John “Mirtillino” with Marion Cave Rosselli, and one, of the funeral in Paris. It also had a facsimile of the Revolutionary Program of Giustizia e Libertà. The text, written in Italian by Salvemini had been translated by Carlo’s wife, Marion Cave.

AC: One year later it was published in Italian…

MC: Yes, in 1938, in Paris, Edizioni di Giustizia e Libertà published the book in Italian, probably based on Salvemini’s text in Italian, with some amendments to the English one. In my archival research, so far, I have not been able to locate the original manuscript, but of course, I am still searching. Interestingly, the 1938 Italian edition featured some changes and additions in the attempt to demonstrate the involvement of Mussolini’s’ entourage in the assassination of the two brothers. This text was reprinted in the collection Scritti vari (Feltrinelli, 1978), which gathers Salvemini’s uncollected writings from 1900 to 1957.

AC: The plot gets thicker as there is one more Italian edition in the mid-1940’s.

MC: The third edition does not have a date but from the additional materials that it includes (references both to the partisan resistance and the fall of Mussolini), we can presume it was written in 1944-45. It was retranslated into Italian by Amelia Rosselli with the aim of keeping the memory of her sons alive in post-war Italy. This version includes new chapters, some revisions, and a previously unpublished Preface, Introduction and Postilla by Salvemini, relating to the Rosselli’s murder which began in 1945 in Rome. While the material executioners had been identified in France as members of the far-right group La Cagoule already in 1938, Salvemini had long maintained that the crime had been masterminded by the Italian Fascists, specifically by Galeazzo Ciano and the military secret service (S.I.M.) The trial aimed at ascertaining who and how the murder had been ordered. Apparently, Mussolini who had previously approved an assassination plan against Carlo was afraid that killing both brothers would backlash against his regime in the international public opinion.

AC: And finally, as further evidence of the interest for this book, there has been a more recent Italian edition in 1999…

MC: Yes, in 1999 Galzerano Editore, a small publisher based near Salerno, translated Salvemini’s 1937 text, enclosing an anastatic reproduction of the first number of the magazine “Giustizia e Libertà”, issued in Paris on 18 May 1934.

AC: What will the new enlarged critical edition that you are now curating, include?

MC: The core is Salvemini’s text with all the final changes of the 1944-1945 edition, notes, and a bibliographical chronology. It will have a critical essay, tracing the editorial history and the context of the book. It will also include some relevant correspondence between Amelia Rosselli and Gaetano Salvemini shedding new light onto their relationship and intellectual exchange.

It was time for a critical edition of this text, one that can provide the necessary historical context, facts, and names that may be not familiar to contemporary readers

AC: The book will be published simultaneously in English by CPL EDITIONS and in Italian by Viella Edizioni, in Rome. The Italian version will be based on Amelia Rosselli’s 1944-1945 translation from the English, while the English version will be based on Marion Cave’s 1937 translation, with the addition of new translations of all of the 1944-1945 additions by Rosselli and Salvemini.

The idea we developed with the enthusiastic support of Cecilia Palombelli (CEO of Viella, one of the most vibrant Italian publisher of history and historiography) is to publish the two versions roughly at the same time, and present them as part of a single editorial project.

MC: I am very glad about this: it will be the first time, that —very much in the spirit of Salvemini and the Rosselli’s— one of their works will be available in Italy and in the Anglo-Saxon world at the same time.

AC: When and how did you first learn about the existence of Salvemini’s book?

MC: In 2000, while I was working on Amelia Rosselli’s memoir (Memorie, Marina Calloni ed., Bologna: Il Mulino, 2001). Paola (one of Nello’s daughters) on behalf of her siblings (Silvia, Aldo, and Alberto) had granted me permission to work on Amelia’s manuscript which had been often quoted but remained unpublished. During that period, as I was searching for supporting materials, the family invited me to visit L’Apparita, the family villa near Florence where, Nello’s study, library, and papers had been preserved, after his widow’s return from the US. Once I realized what a treasure trove that was, with the permission of the family, I spent several months there and began to organize the papers into boxes. Among the many discoveries, I learned about Salvemini’s book and letters.

AC: Beyond marking two anniversaries —80 years since the murder of the brothers and 60 years since Salvemini’s death— your intention seems to aim at promoting the Rossellis’ legacy along the lines traced by Salvemini and Amelia Rosselli.

MC: I would like to move beyond the (by now consolidated) commemoration of Carlo and Nello Rosselli as anti-Fascist heroes and martyrs, and expose their legacy in terms of liberty and freedom as universal concepts. They did not fight only for their own personal freedom, but that of all people living under the oppression of dictatorships. Their individual struggle fits into a long family tradition of political commitment to the idea of freedom and justice, which took different forms at different times.

AC: You are referring back to the previous generations and their struggle for both Jewish emancipation and Italian unification…

MC: Carlo and Nello descended from three distinguished Italian Jewish families, who have been at the forefront of the struggle for liberty. Originally from Rome, and probably of Sephardic origin, the Rossellis —who later moved to Livorno, then London and Pisa— had a long tradition of political engagement. They were closely related to the Nathans, and Ernesto Nathan, who became the first Jewish mayor of Rome (1907-1913), placed the emancipation of the individual and society at the heart of his political program that was based on a profoundly secular conception of the State. The Nathans, in London, had been a point of reference for Italian political dissidents including Giuseppe Mazzini, who later died in the Rosselli-Nathan family home in Pisa. The third important family tradition is that of their mother, born Amelia Pincherle Moravia. A Venetian Jewish family whose members had struggled against the Austrian occupation, and, in 1848, for the freedom of the Repubblica di San Marco.

I think their Jewish origin informed essential aspect of the Rosselli’s worldview. They found themselves being a part of a tiny minority in a Catholic country, thus for them, the struggle for equality and full citizenship was deeply rooted. For them, freedom was a matter of social justice and the respect for human dignity.

AC: Mazzini, in particular, had been a point of reference for the two brothers…

MC: Salvemini points to the fact that Carlo and Nello’s political development was deeply rooted in the Risorgimento and in Mazzini’s example. They adopted Mazzini’s saying ”Pensiero e Azione” (thought and action) that is to say, liberty and justice must be seen pragmatically: it is not enough to think freely, one must be able to act freely as well, for his/her own interest as well as on behalf of the human community at large.

The Rossellis’ political actions mark a continuity between the first Risorgimento and the second Risorgimento, that is the fight against Nazi-Fascism and for the freedom of all citizens.

AC: Regardless of their history the Rossellis’ political legacy did not easily fit into the post-war Italian political landscape…

MC: Militants of Giustizia e Libertà had taken part in the Resistance in Italy and from abroad. Some of them, after their exile in France and in America, played a crucial political role. The Partito d’Azione (Action Party), originated in Giustizia e Libertà and composed by liberal-socialists and republicans, was founded in 1942 but was short lived. It was dissolved in 1946, just after the end of the war and the beginning of the Republican age. After it folded, in a country polarized by the struggle between the Communist Party and the Christian Democratic Party, the Rossellis’ mediation of liberalism and socialism was largely ignored.

AC: Togliatti (the leader of the Italian Communist Party since 1927) notoriously dismissed Carlo Rosselli’s Socialismo liberale (Liberal Socialism), a work that has finally found the attention it deserves on both sides of the Atlantic, only after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

MC: In Italy, the reception of Socialismo liberale, in many ways Carlo’s political testament, has been slow and highly problematic.

It was first published in French in Paris in 1930, and later print in Italian in 1945 by Edizioni U. Yet there was also a clandestine version printed in Milan by Edizioni di Giustizia e Libertà in the first months of 1945 but it was distributed only after the end of the war. Socialismo liberale was not again available until 1973 when Einaudi finally published it thanks to the concerted efforts of John Rosselli (Carlo’s son) and Norberto Bobbio.

AC: In the US, the book was translated and published by Princeton University Press only in 1994.

MC: The credit goes to Nadia Urbinati (editor and author of an insightful introduction) and in a broader sense to the interest in Carlo Rosselli’s ideas repeatedly expressed by Isaiah Berlin and Michael Walzer. Rosselli theorized a full compatibility between individual liberty and social justice, something as relevant today as in 1930.

AC: For many years, you and other scholars working on the Rossellis have been frustrated by the difficulty to access their personal papers. Finally, the Rosselli’s family archive and Nello Rosselli’s personal library have been assigned to the Archivio di Stato in Florence, where it will be digitized cataloged and made available to scholars. What further research are you interested in pursuing within the archive and what are the areas that you believe deserve investigation and attention?

MC: There are many aspects of the Rossellis that are yet to be studied in detail, and I expect much can emerge. Carlo and Nello have been studied mostly by historians and political scientists. My work has focused on the role of Amelia. I approached her from several perspectives: as an author of great interest, as one of the pioneer women to have led an intellectual circle, and for her role in the antifascist Italian diaspora. Through my work with Lorella Cedroni on Amelia, Carlo and Nello Rosselli and on Guglielmo Ferraro and Gina Lombroso, I came to realize that the official narrative and historiography on antifascism, has largely ignored the extraordinary intellectual contribution of these and others Jewish women, both in Italy and in their years in exile, toward the creation of a democratic Italy. Lorella Cedronis’s premature death made it impossible to continue our common project. However, I do plan on working more on Amelia Rosselli, starting from her works from the end of the 19th century.