Samuele Rocca teaches History of Architecture (Medieval, Islamic, and History of Urbanism) at the Ariel University and is a lecturer at the Neri Bloomfield Academy of Design and Education – Haifa. He received his M.A. in Classical Archaeology and History of the Jewish People in the Second Temple Period from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His PhD theses from from Bar – Ilan University was published with the title Herod’s Judaea – A Mediterranean State in the Classical World (Mohr and Siebeck, Tübingen: 2008).

In 2007 he wrote his postdoctorate thesis, The Jews of Roman Italy: A Mediterranean Diaspora between National Identity and Acculturation, at the Pontifical Biblical Institute. He is a recipient of the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture and the Skirball Fellowship for the Study of Christianity. From 2014 till 2016, Samuele was a member of the European Research Council’s project Judaism and Rome. He is Associate Editor of 4 Enoch: The Online Encyclopedia on Second Temple Judaism and Christian Origins (www.4enoch.org), and Member of the Board of Directors, Umberto Nahon Museum for Jewish-Italian Art.

In the last years, Prof. Rocca published various articles dedicated to the status of the Jews in Roman law, including “In the Shadow of the Patriarch: The Organization of the Jewish Communities in Roman Italy in Late Antiquity,” Rassegna Mensile d’Israel, and “From Collegium to Ecclesia: The Changing Outer Framework of the Jewish Communities in Roman Italy,” in Proceedings of the Congress “Citizenship(s) and political-religious self-definitions in the Roman Empire,” “The Collatio and the Future of Rome”, in Iura and Legal Systems 4, 2017. His essay “In the Shadow of the Temple: Depicting the Menorah in Ancient Art” is published din the catalogue of the exhibition La Menorà, culto, storia, e mito, organized by the Jewish Museum of Rome and the Vatican Museum.

This essay is published in connection with the Rome Lab and the exhibition The Arch of Titus: From Jerusalem to Rome and Back presented at the Center for Jewish History by Yeshiva University Museum, Centro Primo Levi, and the Jewish Museum of Rome jointly with their academic partners.

For both the Jews living in Judaea and those living in the Diaspora, the Jewish War was an historical watershed. The most evident result of the war was the destruction of the city of Jerusalem and its Temple razed to the ground by the Roman soldiers. The spoils of the Temple were brought to Rome. This tragic event spread the image of the Roman victory over the Jews throughout the Empire. At the same time, it announced the rise of a new imperial family, the Flavians, who came from obscure Italic origin and gave rise to a new imperial ideology quite distant from that which characterized the rule of Augustus.

In 71 C.E., according to the best Roman tradition, Vespasian and Titus celebrated their triumph on the Jews in the capital of the Empire. They used this sumptuous ceremony as the political and ideological platform to legitimize the new dynasty. The procession left a deep mark and was evoked in a vast range of images placed on coins and monuments, both instruments of Roman propaganda.

Shortly after the victory, the new rulers minted a new series of coins called Judaea Capta, with the purpose of commemorating the victory on the Jews. Themes from these coins also appears on coins produced in the Hellenistic East, or by loyal allies, such as King Agrippa II. The Judaea Capta series, produced during the reigns of Vespasian, Titus and – at the beginning of Domitian’s, circulated the news of the Roman triumph to all social strata of the population of Roman Italy and the provinces.[1]

In Rome, two arches built by the last Flavian ruler, Domitian, are the main memento of the Roman triumph on Judaea. One stood in the Circus Maximus and the other on the Velia hill. These two monuments, built when Titus had already died, do not simply celebrate the Roman victory on over the Jews, but also stand as a glorification of the whole Flavian family: Vespasian and his two sons and heirs, Titus and Domitian.

The two triumphal arches were part of a larger plan of urban reform through which the Flavians, sought to immortalize their power, as Augustus had done more than a century earlier.

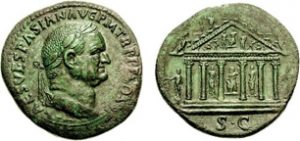

In 71 C.E., when the Flavians celebrated their triumph, Rome still bore the scars of the huge conflagration, at the end of Nero’s rule, which had destroyed most of the city in 64 C.E. Besides, Rome had also suffered great damage during the civil war of 69 C.E. when the Capitol, the Temple dedicated to the Capitoline Triad, had been completely burned down. The Flavian planned to rebuild Rome, immortalized on coins that bear the caption Roma Resurgens (image1), gave a new face to this grim past reshaping the city through the Forum Pacis, the Flavian Amphitheater known as Coliseum, two or perhaps three triumphal arches, as well as the new imperial palace erected by Domitian on the Palatine, and various other monumental buildings, such as the Bath House of Titus, and the Stadium of Domitian, today Piazza Navona.

At the root of the Flavian narrative was the brutal repression of the rebellion of Judaea, a province of the Roman empire. Through the transformation of a relatively small intervention into a full-fledged war with a highly symbolic and rich loot, the Jewish war was presented as the triumph over a powerful foreign enemy echoing Augustus’s triumph over Cleopatra and the Parthians.

The celebration of a victorious war on the “other,” served imperial propaganda, magnified the players of the story, and blurred the reality behind it: two ferocious civil wars. One was fought within the Roman world and brought about Vespasian’s annihilation of his political enemies and the establishment of a new regime of clear autocratic ambitions. The other was fought among different groups of Jewish rebels who spent a great deal of resources to kill one another bringing the population of Jerusalem to starvation. Jews fought on both sides and those who stood by Rome were prominent and conspicuous. The Jewish king Agrippa II, scion of Herod the Great, who ruled on large areas of Galilee, Batanaea, and Gaulanitis, was the most important ally, or socius, of Rome during the war, providing not just auxiliary soldiers, but also strategic advice assisted by Berenice, the king’s sister and allegedly Titus’ lover.

On the same side was Tiberius Julius Alexander, the equestrian prefect of Egypt, son of the alabarch, who chose to support the bid of Vespasian for the imperial throne, putting the army, which garrisoned Egypt, at his orders. Tiberius Julius Alexander directed the military operations during siege of Jerusalem. He was later rewarded with the most prestigious prefecture of the praetorium, the peak of the equestrian career, which made him, a Jew from Alexandria, the closest person to the imperial throne.[2]

In the seventh book of the Jewish War, Josephus describes in detail the Flavian triumph of 71 C.E. Although Josephus focuses only on selected episodes and leaves out important information, his is the only known account of a triumphal procession in the early Empire.[3]

One of the most striking elements of Josephus narration is that from the opening passages he identifies the key tenet of Flavian ideology, namely the emperor’s power to choose his own heirs, in this case his sons, who would continue his policy and guarantee peace. Josephus states that Titus and Vespasian celebrate the triumph “both of them together”. They exit the Temple of Isis and are joined by Domitian on a horse. The image of the three Flavians proceeding through the Via Sacra not only seals the end of the Jewish War, the topic of Josephus’ book, but also celebrates his Flavian patrons and the unity of the family. This choice, the guarantee of succession, was presented as a requisite for peace, or pax, welfare, or fortuna, and symbolized the emperor’s providentia.[4]

The triumphal ceremony opened at the Temple of Isis and Serapis in the Campus Martius.[5] Vespasian and Titus spent the whole night in the temple. At dawn, they exited to see the imperial title, bestowed upon them by the army during the final days of the siege of Jerusalem, ratified by the senate and the people of Rome. The two men sat on the ivory curule chairs, a symbol of authority, having been praised by the army, they offered their customary prayers. Only then the triumphal procession started.

Josephus’s description of the triumph highlights the connection between the Flavians and the Eastern divinities, Isis and Serapis, which carried a special meaning in their history.[6] The first part of the procession was opened by magistrates and senators, followed by soldiers carrying precious objects, and by the Jewish captives. The latter were dressed with a great variety of garments in fine texture, whose purpose was to conceal their deformities and the wounds suffered on the battlefield. Soldiers marched behind, displaying painted banners that depicted the most important battles, as well as models of captured cities. Josephus describes these objects in great detail.

The soldiers marched behind this procession carrying the spoils of Jerusalem’s Temple which included, as we see carved in Arch of Titus, the Menorah, the golden seven branches lampstand, the show bread table and the horns, which were used to announce the coming of the Shabbat, as well as a copy of the Jewish Law. All these objects were later set in the Temple of Peace, erected by Vespasian to celebrate his victory. The loot was followed by chryselephantine statues of Victoria.

The second part of the procession is not described in the same detail. According to Peter Connolly, this part of the procession was opened by white sacrificial oxen followed by two prisoners, Yochanan of Gush Halav and Simon Bar Giora. These were the Zealots leaders, who directed the defense of Jerusalem, and afterwards surrendered to the Romans. Before the triumph, they were probably held in the Tullianum, or the state prison of Rome, located in the forum. The two prisoners were displayed on a stand carried by soldiers, together with a trophy composed by a set of armor, shields, and weapons taken from the enemy on the battlefield.

Josephus, instead, focused on the Flavians, who closed the procession. Vespasian, and Titus rode a quadriga, drawn by four horses, and by Domitian, Vespasian’s younger son, who did not take part in the Jewish War. Behind them, stood a slave holding olive branches and whispering to both that they were mere humans, not gods. White clad soldiers singing Io Triumphe, and waving olive branches heralded the end of the ceremony.[7]

From the Temple of Isis, far away from the city center, the procession continued on the Via Sacra, or triumphal avenue, passing through the forum, and ending in front of the Capitoline Hill. There, Shimon Bar Giora was conducted to the Tarpean rock, and beheaded. After the execution, the emperors ascended the steps of the Capitoline Hill and concluded the ceremony with a sacrifice by the Temple of Jupiter (image 2).

This temple, representing the senatorial aristocracy, had been destroyed during the civil war and rebuilt by Vespasian with revenues from the fiscus iudaicus.

If Josephus’s description of the ceremony remains one of the most important testimonies of Flavian propaganda, the Judea Capta coins can help us understand the ideology of the new ruling family.[8]

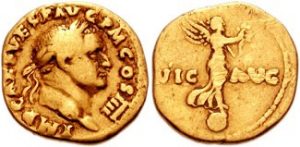

An analysis of various series of coins minted by the new dynasty shows that the Flavians considered the victory over the Jews a central element of their public image. Most of these coins depict Victoria, the goddess of victory, one of the most important contributions of the emperor to Rome (image 3), as w ell as on the representation of Judaea as a woman in mourning.

ell as on the representation of Judaea as a woman in mourning.

Other coins minted by the first two Flavian rulers, mainly Vespasian, focuses on Pax, or peace, often as Pax Augusta, or peace brought through the efforts of the emperor (image 4).

Clearly Pax, or peace, was seen as the inevitable consequence that only military victory could achieve. Other coins depict Titus and Domitian, marking the idea of providentia, or providence, through the celebration of Vespasian’s heirs, or through the depiction of the Ara Providentiae Augustae, or altar dedicated to imperial providence, erected between the years 14 and 17 C.E. (image 5).

Indeed, the idea of providentia, the Emperor’s ability to foresee the future and ensure the well-being and prosperity of the Roman citizens was adopted as one of the distinctive divine trait of the Flavians. Less celebrated on Vespasian’s coins, are some of the main consequences of peace, namely Concordia and Felicitas. Concordia celebrated as Concordia Augusti (image 6), emphasizing the association between the emperor and the goddess, who embodied the idea of concord.

Concordia was a universal concept, referred to the family, to man and wife, and the Imperial family. Moreover, from 69 C.E., the new ideal of concordia exercituum, or harmony of the armies, began to be advertised. Hence, the depiction of Concordia, could indicate the idea that Vespasian had the unanimity of the army’s support.

Besides, the concept of concordia, was also closely related to that of pax.

Felicitas, on the other hand, express a general ideal of happiness (image 7).

The celebration of felicitas by the new regime is very important as it serves to emphasize the autocratic nature of the new dynasty. In fact, opposed to the ideal of felicitas stands that of libertas. No less important is the celebration of Fortuna, or Fortune, the goddess which promoted in the difficult circumstances, the rise of the Flavians (image 8). Vespasian celebrated the return to peace with the edification of the Templum Pacis, the Temple of Peace which celebrated both the end of the civil wars and the Pax Romana, the peace imposed by the Romans on conquered peoples.

The classic Augustan ideals of virtus, or bravery, iustitia, or justice, pietas, or piety, clementia, or clemency, and libertas, or liberty, are seldom mentioned, or do not appear at all.

By the end of Domitian’s reign, the image of the Flavians dominated the city of Rome through a series of public buildings erected during their rule.[9] These included the Forum Pacis, built by Vespasian, the Baths of Titus and the Coliseum, built by Titus, the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, the Domus Flavia, or the huge palatial mansion erected by Domitian on the Palatine Hill, and the Stadium of Domitian.

Many of these public buildings laid emphasis on the successful outcome of the Jewish War, bestowing an enduring legitimacy on the new dynasty.[10]

The Forum Pacis, was the earliest, and probably the most important building associating the Flavians to the Jewish War. The building, was located in the Roman Forum and was in fact a temple with no civic function. The Templum Pacis was announced in 70 C.E. and was completed five years later in 75 C.E. (image 9).

According to Josephus, the temple housed the Menorah as well as all the other objects of worship looted from the Temple of Jerusalem and brought to Rome as depicted on the relief of the Arch of Titus.[11]

The more modest Temple of Vespasian and Titus, celebrated the divine connection of father and son, who had acquired their military authority on the battlefields of Judaea. It was their victory over the Jews, which elevated the obscure general to the peak of power. The temple was located on the western edge of the forum and was dedicated by the Senate to Vespasian during the reign of Titus. The building however was completed only 9 years later and dedicated by Domitian to the memory of his brother. Together with the facing Temple of Julius Caesar, it was the only temple of the Roman Forum dedicated to a deified emperor.[12]

The Bath-House of Titus stood near the Coliseum (image 10) and was completed in time for its inauguration in 80 C.E. The rectangular structure was preceded by a monumental stairway and a portico to the south, associating visually the building to the Coliseum.

A terrace, probably used as garden or exercise yard, preceded the bath block which included the frigidarium, the tepidarium, and the calidarium. This hall was flanked by two square palestrae, or exercise yards, surrounded by porticoes. Although no inscription directly connects the building to the Jewish War, its closeness with the Coliseum, points to the possibility that this building too was financed through the loot from the Temple of Jerusalem. This association was indirectly publicized to the people of Rome offering a new service, the bath house, in celebration of the Flavian triumph.

A well-known inscription indicates that the Flavian amphitheater known as the Coliseum was financed with the huge loot taken from the Temple of Jerusalem. Vespasian ordered its construction in 72 C.E. and it was inaugurated in 80 C.E. by Titus, with spectacular games described by Martial, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio.[13] The Coliseum stood nearby the Arch of Titus, located on the Velia, as well as the Baths of Titus. The monumental building consists in an elliptic structure 620 feet long and 511 feet wide, built in stone and concrete. The round facade developed over four stories. The upper arches were designed in alternate Tuscan, Dorian, Ionian and Corinthian order. The auditorium or cavea, where the audience was accommodated, had a capacity of 87.000. It was divided in various parts. At the bottom, there was an area reserved for the Senators and special boxes for the emperor and Vestal virgins. Members of the equestrian order sat on the next tier, followed by the richest members of the plebs. The upper part was used for the poorest citizens. Although the auditorium was not roofed sunshades, or velaria, could be pulled overhead to provide relief from rain or sunlight. The original platform where the games were performed was made of wood. Underneath were vaulted chambers used for the gladiators and the wild animals’ cages. A system of elevators brought the performers on and off the stage during the games. The Flavian Amphitheater was the first building of its kind and replaced the traditional theaters of the Augustan period, such as the Theater of Marcellus.[14]

And now we come to the central symbol of the Jewish War, the Arches of Titus. Although the relief depicting the triumph and the golden Menorah became universally renown, there were two the arches erected to celebrate the victory of the Jewish War: one on the Velia hill and one in the Circus Maximus. The two arches are the only explicit celebration of the Jewish War and were placed in a strategic position, which emphasized the military achievements of the new dynasty and defined the Flavian reshaping of the city center.

The first arch stood in an area that dominates the lower valley. There, at the intersection of the Caelian, Esquiline and Palatine hills, rose the grandiose Flavian Amphitheater. The Arch of Titus could be seen from key places in the city center. People going in and out the Coliseum, as well as visitors of the forum where the Senate House was located, were reminded of the military achievements of Vespasian and Titus. No less dominant was the second triumphal arch, located on the eastern side of the Circus Maximus which, until the inauguration of the Coliseum, was the most popular entertainment venue in Rome. Both arches were meant to impress on the masses the triumph of the emperor in a war against a foreign enemy and the prosperity it brought the Roman people.

The Arch on the Velia was erected in 81-82 C.E., during the reign of Domitian, using Pentelic marble (fig. 11). The work likely began during the rule of his brother Titus. The fact that by the completion of his arch, Titus was already dead, is made clear by one of the depiction of the apotheosis depicted on the ceiling of the archway and by the inscriptions (image 12). The Arch of Titus may have been the work of Rabirius, the architect who designed the Domus Augustana, Domitian’s palace on the Palatine.[15]

The surviving inscription, “the Roman senate and people (dedicate this arch) to the divine Titus Vespasianus Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian,” is set on the western attic (image 12).[16] In its concise form, the inscription conveys the legitimization of the imperial dynasty through the dedication of the Senate and the people of Rome. It was crucial for the Flavians to present themselves as appointed by the will of the Senate and the People while in fact they had risen to power through a tumultuous civil war.[17]

The inscription also implies that the legitimacy is transferred from one Flavian ruler to the next. Titus, already divine, is portrayed as the son of the divine Vespasian. Thus, both father and son, divine, add to the legitimacy of Domitian, who in fact completed the arch.

Moreover, the depiction of the loot on the relief, serves to remind future generations, one of the main archetypes of Roman propaganda, namely, the benefits of the empire, the war and the peace (image 13). The gold and silver objects, the rich textiles, the enormous quantity of wealth collected and brought to Rome from foreign regions are the legitimate reward of conquest.[18] The Arch of Titus is indeed a dynastic monument in which Vespasian’s and Titus’ achievements ultimately serve to give prominence to Domitian who, in fact, built it. Departing from the description of the triumph given by Josephus, in which Domitian is portrayed as riding on a horse, on the Arch, Domitian occupies a conspicuous position and is paired with his patron goddess, Minerva.[19]

The second arch, whose existence has been known since the Middle Ages and of which only fragments have survived, was probably bigger and was located on the eastern edge of the Circus Maximus (Fig. 14). [20]. It was completed by Domitian in 81 C.E. following the death of his brother and located in a highly symbolic position.

The Circus Maximus was where the emperor met the people of Rome during the ludi, or public games, held on the occasion of Rome’s religious festivals. It was built at the feet of the Palatine, the traditional seat of Imperial power from Augustus onwards. It was there that the people of Rome could acclaim the emperor and show him their favor.

In contrast to the arch on the Velia, this second one consisted of a wider arch, higher and wider, flanked by two smaller arches, each framed by a column on either side. The arch was topped by an attic, with an inscription. This arch, as well, was decorated with reliefs. The only remain is a fragment, which depicts a soldier, possibly showing his virtus, or bravery.[21]

The main inscription, which topped the arch, was copied a long time ago. The inscription reads: “The senate and the people of Rome (dedicated this arch) to the emperor Titus, Caesar, son of the divine Vespasian, Augustus, high priest of the Roman state, holder of the tribunician power for the tenth time, (acclaimed) imperator for the seventeenth time, consul for the eighth time, father of the country, their leader, (who), following the orders of his father and the advices of Providence, subjugated the Jewish people and destroyed the city of Jerusalem, which had been previously attacked in vain by military leaders, kings, and peoples, who did not succeed in conquering (it).”[22] Since the city of Jerusalem had already been conquered numerous times including by the Romans: by Pompey in 63 B.C.E., by Herod and Sosius in 37 B.C.E., and by Varus in 4 B.C.E., the second arch reinforces the idea that the victory on the Jews served to enhance imperial propaganda.

In conclusion, we can advance the hypothesis that the Jews took the place of the Egyptians defeated at Actium, or of the British tribes conquered by Claudius in the Roman imagination. The victory on the rebel province was celebrated though the minting and circulation of coins as well as through the erection of various monuments, such as the Forum Pacis, where the spoils coming from the Temple of Jerusalem were preserved and displayed, or the two triumphal arches, dedicated by Domitian to Titus. Further, the loot coming from the war, financed the construction of unprecedented monuments including the Coliseum and the Bath of Titus.

No less than Augustus, the Flavians were the first rulers to implement a swiping plan of urban reform, which reshaped the whole city of Rome in function of the advent of the new dynasty and its indelible power. Unlike previous emperors, the Flavians sought to dominate with their presence the urban public space and the collective mindset of Rome.

Bibliography:

Beard, M., “The Triumph of Flavius Josephus” in Boyle, Anthony J. and Dominik, William J., (eds.), Flavian Rome, Culture, Image, Text, Brill, Leiden 2003, p. 543-558.

Beard, M. and Hopkins, K., The Colosseum, Cambridge (Mass.) 2005.

Cappelletti, S., The Jewish Community of Rome, From the Second Century B.C. to the Third Century C.E., Journal for the Study of Judaism Supplement Series 113, Leiden 2006.

Coarelli, F., “I Flavi e Roma”, in Coarelli, F. (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 68-97.

Cody, J.M., “Conquerors and Conquered on Flavian Coins”, in A.J. Boyle and W.J. Dominik (eds.), Flavian Rome, Culture, Image, Text, Leiden 2003, pp. 103-124.

Connolly, Peter, Greece and Rome at War, London 1981.

Firpo, G., “La guerra giudaica e l’ascesa di Vespasiano”, in Coarelli F. (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 42-45.

Foss, C., Roman Historical Coins, London 1990.

Gaggiotti, M., “Templum Pacis: una nuova lettura”, in Coarelli, F. (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 168-176.

Galinsky, K., Augustan Culture, An Interpretative Introduction, Princeton (N.J.) 1996.

Goodman, M., “The “Fiscus Iudaicus” and Gentile Attitudes to Judaism in Flavian Rome”, in J. Edmondson, S. Mason, J. Rives (Eds.), Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome, Oxford 2005, pp. 167-177.

Henderson, J., “Par Operi Sedes: Mrs. Arthur Strong and Flavian Style, the arch of Titus and the Cancelleria Reliefs”, in A.J. Boyle and W.J. Dominik (eds.), Flavian Rome, Culture, Image, Text, Leiden 2003, pp. 229-254.

Hölscher, T., “Rilievi provenienti da monumenti statali del tempo dei Flavi”, in Coarelli F. (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 46-61.

Jones, Brian W., The Emperor Titus, Routledge, London 1984.

Kleiner, Diane E.E., Roman Sculpture, New Haven (Conn.) 1984.

La Rocca, E., “Templum Gentuis Flaviae”, in Coarelli, F. (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 224-233.

Levick, Barbara, Vespasian, Roman Imperial Biographies, Routledge, London 2005.

Magness, J., “The Arch of Titus and the Fate of the God of Israel”, Journal of Jewish Studies 69, 2008, pp. 201-217.

Mattingly, H. and Carson, R.A.C., Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum II, Vespasian to Domitian, London Methuen 1966.

Meshorer, Y., Ancient Jewish Coinage II, Herod the Great through Bar Cochba, New York 1982.

Meshorer, Y., A Treasury of Jewish Coins, From the Persian Period to Bar Kokhba, Jerusalem 2001.

Millar, Fergus, “Last Year in Jerusalem: Monuments of the Jewish War in Rome,” in Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome (eds. Edmondson Jonathan, Mason Steve, Rives James; Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005, p. 101-128.

Noreña, Carlos F., Imperial Ideals in the Roman West, Representation, Circulation, Power, Cambridge 2011.

Platner, S.B. and Ashby, T., A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, Oxford 1929.

Ranucci, S., “La monetazione dei Flavi. Caratteri generali e aspetti tipologici”, in Coarelli, F. (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 358-367.

Rajak, Tessa, Josephus, The Historian and His Society, Duckworth, London 2002.

Rocca, S., “Domitian’ Attitude towards the Jews in the Light of his Numismatic Output”, in B. Zissu, (ed.), Israel Numismatic Journal 18, Volume in Memory of Dan Barag, pp. 122-145.

Schürer, E., The History of the Jewish People in the age of Jesus Christ 1, Edinburgh 1987.

Southern, P., Domitian, Tragic Tyrant, London 1997.

Strong, David, Roman Art, The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, Harmondsworth 1992.

Tucci, P.L., “Nuove osservazioni sull’architettura del Templum Pacis”, in Coarelli, F. (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 158-167.

Turner, E.G., “Tiberivs Ivlivs Alexander”. JRS 44, 1954, pp. 54–64.

Ward-Perkins, J.B., Roman Imperial Architecture, Penguin, Harmondsworth 1981.

Yegül, F., Baths and Bathing in Classical Antiquity, Cambridge (Mass.) 1995.

Zanker, P., The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (Thomas Spencer Jerome Lectures), Ann Arbor (Mich.) 1990.

Endnotes

[1] On the Judaea Capta series, see Y. Meshorer, A Treasury of Jewish Coins, From the Persian Period to Bar Kokhba, Jerusalem 2001, pp. 185-191. See also J.M. Cody, “Conquerors and Conquered on Flavian Coins”, in A.J. Boyle and W.J. Dominik (eds.), Flavian Rome, Culture, Image, Text, Leiden 2003, pp. 103-124. See also S. Ranucci, “La monetazione dei Flavi. Caratteri generali e aspetti tipologici”, in F. Coarelli (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 359-360.

[2] See on Agrippa II, Y. Meshorer, Ancient Jewish Coinage II, Herod the Great through Bar Cochba, New York 1982, pp. 192-193. See also Y. Meshorer, A Treasury of Jewish Coins, From the Persian Period to Bar Kokhba, Jerusalem 2001, pp. 102-114. See also E. Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the age of Jesus Christ 1, Edinburgh 1987, pp. 471-483. On Tiberius Iulius Alexander see E.G. Turner, “Tiberivs Ivlivs Alexander”. JRS 44, 1954, pp. 54–64.

[3]See Josephus, Jewish War VII, 19-162. See also M. Beard, “The Triumph of Flavius Josephus”, in A.J. Boyle, and W.J. Dominik, (eds.), Flavian Rome, Culture, Image, Text, Brill, Leiden 2003, p. 550, 552-555. See P. Connolly, Greece and Rome at War, London 1981, p. 247-248.

[4] See M. Beard, “The Triumph of Flavius Josephus”, in A.J. Boyle, and W.J. Dominik, (eds.), Flavian Rome, Culture, Image, Text, Brill, Leiden 2003, pp. 555-558.

[5] See M. Beard, “The Triumph of Flavius Josephus”, in A.J. Boyle, and W.J. Dominik, (eds.), Flavian Rome, Culture, Image, Text, Brill, Leiden 2003, p. 551.

[6] Vespasian, when he was in Alexandria in 69 C.E., was acclaimed by the army stationed there as imperator, and celebrated the event in the Serapeum. Thus, the eastern god, as previously the god on Mount Carmel, or the prophecy of Josephus, consecrated Vespasian as the legitimate ruler of the Roman Empire, bestowing on him the favor of the gods. Besides, as narrated by Suetonius, during the civil war in Rome in 69 C.E., the young Domitian had to flee from the partisans of Vitellius, dressed as a priest of Isis. On the acclamation of Titus on the field during the final stages of the conquest of Jerusalem, see Josephus, War VI.316-317. On the acclamation of Vespasian as emperor in the Serapeum of Alexandria, see Suetonius, Life of Vespasian 7. On Domitian’s fleeing from the partisans of Vitellius dressed as priest of Isis see Suetonius, Life of Domitian 1.

[7] See P. Connolly, Greece and Rome at War, London 1981, p. 248. See on the costume donned by Vespasian and Titus, Dionysus of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities II.34.

[8] On Flavian coins, see S. Ranucci, “La monetazione dei Flavi. Caratteri generali e aspetti tipologici”, in F. Coarelli (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 358-367. On Roman imperial ideology, as forwarded on Roman coins, see C. Noreña, Imperial Ideals in the Roman West, Representation, Circulation, Power, Cambridge 2011, pp. 27-179.

[9] On the Flavian’s building program, see F. Coarelli, “I Flavi e Roma”, in F. Coarelli (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 68-97.

[10] See F. Millar, “Last Year in Jerusalem: Monuments of the Jewish War in Rome,” in J. Edmondson, S. Mason, J. Rives (eds.), Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome, Oxford 2005, pp. 101-128.

[11] See Josephus, Jewish War VII, 161-162. There have been many debates among scholars concerning the location of the Menorah. It has been speculated that the cultic objects coming from Jerusalem in a way symbolized the support of the Jewish God to Rome, the fact that he took side with the Romans. That does not mean of course that the temple was also a temple dedicated to the Jewish God. In a room located west to the temple, was located the well-known Forma Urbis, or the marble made plan of the city of Rome, dating from the Severan period. See F. Millar, “Last Year in Jerusalem: Monuments of the Jewish War in Rome,” in J. Edmondson, S. Mason, J. Rives (eds.), Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome, Oxford 2005, pp. 101-128. See also J.B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture, Penguin, Harmondsworth 1981. See also P.L. Tucci, “Nuove osservazioni sull’architettura del Templum Pacis”, in F. Coarelli (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 158-167. M. Gaggiotti, “Templum Pacis: una nuova lettura”, in F. Coarelli (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, pp. 168-176. Gaggiotti argues that in fact Pax was no less than the Jewish God, who was also known as Shalom, or Peace. The Flavians, thus brought the Jewish God to Rome, erecting him aa shrine, the Temple of Peace.

[12] See S.B. Platner, T. Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, Oxford 1929; p. 556.

[13] The inscription reads “I[mp(erator)] T(itus) Caes(ar) Vespasi[anus Aug(ustus)] / amphitheatru[m nouum (?)] / [ex] manubi(i)s (vac.) [fieri iussit (?)]”. Thiis can be translated as “The emperor Titus Caesar Vespasian Augustus had the new amphitheatre built from the profits of the war”. See G. Alföldi, “Eine bauinschrift aus dem Colosseum”, ZPE 109, 1995, pp. 195-226. See fort he main ancient sources, Martial, Epigrams 1.6.41; Martial, On Spectacles; Suetonius, Life of Titus VII-IX; Suetonius, Life of Domitian IV.1; Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.25; LXXIX.25.2-3.; SHA, Life of Antoninus Pius VIII.2; Life of Helagabalus XVII.8; Life of Alessander Severus XXIV.3; Life of Maximinus and Balbinus I.4; Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History XVI.10.14.

[14] See M. Beard, and K. Hopkins, The Colosseum, Cambridge (Mass.) 2005. See also J.B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture, Harmondsworth 1981. It seems that the inaugural games included venatio, or hunt of wild animals, public executions, naumachiae or mock sea battles, and gladiatorial games. No less than 5000, according to Eutropius, possibly 9000 wild animals (Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.25), such as wild bulls, lions, elephants, ostriches, were killed during the inaugural games. Public executions were performed during the interval between one game and another. These included probably damnatio ad bestias – the culprit was tied to a pole and given to wild animals –, and crucifixion. According to Martial, a woman was executed by a wild bull, reenacting the myth of Pasiphae (Martial, On Spectacles 6.5). To hold mock sea battles, the amphitheater was flooded. It seems, according to Cassius Dio, that first a naval battle between the Corinthians and the Corcyreans was reenacted, and then between the Athenians and the Carthaginians. Gladiatorial games followed. Martial records the fight between a couple called Verus and Priscus (Martial, On Spectacles 31).

[15] See D.E.E. Kleiner, Roman Sculpture, New Haven (Conn.) 1984, p. 183.

[16] The inscription reads, “SENATVS POPOLVSQVE ROMANVS DIVO TITO DIVI VESPASIANI FILIO VESPASIANO AVGUSTO” (Senatvs Popolvsque Romanvs divo Tito divi Vespasiani filio Vespasiano Augusto), or The Roman Senate and People (dedicate this) to the divine Titus Vespasianus Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian. See CIL VI, 945, ILS I, 265, p. 83.

[17] See, Tacitus, Histories I.4.

[18] See M. Beard, “The Triumph of Flavius Josephus”, in A.J. Boyle and W.J. Dominik (eds.), Flavian Rome, Culture, Image, Text, Leiden 2003, p. 551.

[19] See D.E.E. Kleiner, Roman Sculpture, New Haven (Conn.) 1984, p. 187.

[20] The Circus Maximus, located at the feet of the Palatine, could seat an audience of 150.000, was 621 m long and 118 m large. The building, which possibly dated to the rule of the Etruscan kings, had by then a long history. The original building was erected using timber. The wooden structure was enlarged by Julius Caesar. Augustus in 31 B.C.E. added a pulvinar, or an elevated stand, and an obelisk, whose task was to remind the public of his victory at Actium. Claudius as well repaired the building. The main purpose of the building was to host chariot races.

[21] See F. Millar, “Last Year in Jerusalem: Monuments of the Jewish War in Rome,” in J. Edmondson, S. Mason, J. Rives (eds.), Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome, Oxford 2005, p. 101-128. See also T. Hölscher, “Rilievi provenienti da monumenti statali del tempo dei Flavi”, in F. Coarelli (ed.), Divus Vespasianus, Il bimillenario dei Flavi, Milano 2009, p. 50.

[22] The inscription reads: senatus populusq. Romanus imp. Tito Caesari divi Vespasiani f./Vespasian[o] Augusto pontif. max., trib. pot. X, imp. XVII, [c]os. VIII, / p. p., principi suo, quod praeceptis patr[is] consiliisq. et auspiciis gentem/ ludaeorum domuit et urbem Hierusolymam , omnibus ante se ducibus/ regibus gentibus aut frustra petitam aut omnino intem[p]tatam, delevit. This can be translated as ” The senate and the people of Rome (dedicated this arch) to the emperor Titus, Caesar, son of the divine Vespasian, Augustus, high priest of the Roman state, holder of the tribunician power for the tenth time, (acclaimed) imperator for the seventeenth time, consul for the eighth time, father of the country, their leader, following the orders of his father and the advises of the Providence, subjugated the Jewish people and destroyed the city of Jerusalem, which had been previously attacked in vain by military leaders, kings, and peoples, who did not succeed in conquering”. See CIL VI, 944, ILS I, 264, p. 83.