Elizabeth Schächter, The Jews of Italy 1848–1915 Between Tradition and Transformation, Vallentine Mitchell, 2011

Much has been written about the Jews during the Fascist regime, but the period from the second emancipation (1848) until the First World War is largely uncharted territory in the English-speaking world. The notable exception is Cecil Roth’s The History of the Jews of Italy which appeared more than sixty years ago. And it is only in the last decades of the twentieth century that Italian scholars began to publish on this epoch. A substantial part of their research, however, relates to specific Jewish communities of which emancipation is but one aspect. Thus the aim of The Jews of Italy is to fill a major gap in our knowledge and to present Italian Jewry, the largest ethnic minority in the nineteenth century, to a wider public within a European context.

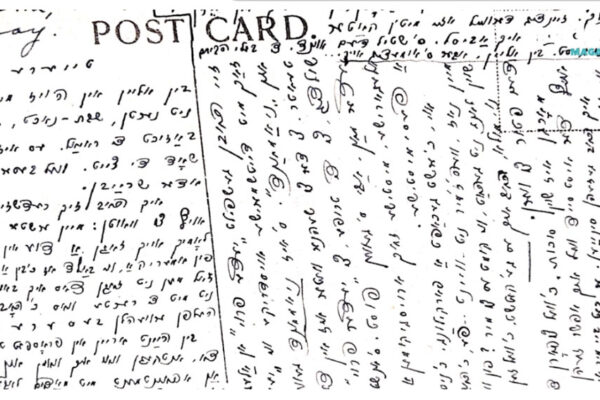

The intention is not to present a comprehensive, chronological survey of political and social development, but to examine the issues which were considered the principal areas of concern to the Jews themselves. The primary focus is the integration – in the sense of a previously segregated group entering society in equal participation – of the Jews from their perspective; their response to the changing patterns of their lives recorded in memoirs, autobiographies, oral testimony, private correspondence, and the views of their religious leaders. The poor and the unlettered are not neglected: through sources such as census data, judicial records, interviews and archival material, their presence is also preserved, although it has to be said that the focus inevitably favours the middle classes whose legacy is more voluminous.

Alongside these familial and individual micro-histories, another fundamental contemporary source is the Jewish periodical press which played a key role in the dissemination of ideas. Two journals spanned the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, L’Educatore Israelita (later Il Vessillo Israelitico, 1853-1922) and Il Corriere Israelitico (1862-1915). In addition, two other influential publications are considered: La Settimana Israelitica (1910-1915) which signalled an intellectual and spiritual renewal initiated by the Chief Rabbi of Florence; and L’Idea Sionista (1901-1911), reflecting to a large extent the activities of the Federazione Sionistica Italiana also founded in 1901. These journals testify to initiatives on the part of individual members from disparate Jewish communities to communicate with their co-religionists and thus shape the cultural and religious development of Italian Jews during this crucial period of change.

At the period of Unification, Italian Jewry was some forty thousand in number, accounting for one per cent of the total population. However, mere numbers can be misleading as the Jews were not evenly dispersed: they were scattered among sixty-seven communities, a third of which contained fewer than 200 people, whereas in others such as Livorno and Rome, they constituted 4.06% and 2.2% respectively of these cities’ inhabitants. The large settlements of southern Italy and Sicily had been expelled in the sixteenth century during the Spanish occupation; they were also kept out of Lombardy until Austrian rule replaced the Spanish in 1714.

March 29, 1848 is the date of the Statuto Albertino when Carlo Alberto, King of Piedmont and Sardinia, granted the Jews civil and political equality which was extended to the whole of Italy as it became unified, concluding in 1870 with the annexation of the Papal States and the abolition of the Jewish ghetto in Rome. The Waldensians, Italian Protestants of western Piedmont, had been given the same rights a month earlier. Between 1800 and 1815, during Napoleon’s rule of Italian territories, both minorities had enjoyed the freedoms accorded to French Jews and Protestants in 1791. This is known as the first emancipation. The end date of this study, 1915, is the year that Italy entered the First World War. It signifies the culmination of Jewish patriotism: for the many Jews who were ready to sacrifice their lives for their country, the war would be the ultimate demonstration of their unqualified italianità.

The introductory chapter serves to set the scene as it were and to discuss key concepts such as the nature of Jewish emancipation; assimilation; and definitions of Jewish identity. The second chapter explores the complex process that has been called ‘the anguish of assimilation’: the tensions and pressures arising from acceptance in the host society and retention of Jewish patrimony; the relationship between Jewish identity and nascent national identity; the shared aspirations of Jews and non-Jews in the emerging Italian nation which led to active participation in public life. The hypothesis expounded and illustrated in this chapter is the re-shaping of Jewish identity, the co-existence of a plurality of identities.

The third chapter examines the ways in which the Jewish communities were modified by the new political order of the Italian nation. Prior to emancipation, they were autonomous entities whose governing bodies regulated religion, education and welfare, and held judicial courts. As a result of internal migration to the principal cities which occurred throughout emancipated Europe, small communities were depleted. As a manifestation of their success and collective identity, the larger communities constructed monumentally magnificent synagogues in, for example, Florence, Rome and Turin. Continuities were maintained through many institutions, in particular the traditional philanthropic associations, and other forms of cohesion evolved around new causes. One prominent example was the transnational Alliance Israélite Universelle established in Paris in 1860, with branches throughout central and Western Europe.

It is no longer the case that the history of Italian Jews since Unification can be described in terms of unqualified success and as such can be presented as an anomaly with regard to European Jewry. This uncritical and hagiographic interpretation has been challenged. The introduction of the Racial Laws of 1938 can only be completely understood if they are considered not as a break with the past, but as a continuation of a tradition of discrimination and clerical anti-Judaism deriving from the consequences of emancipation. Chapter four evaluates the contemporary debates on this major issue in Italian Jewish historiography. In addition, the pivotal role of the Roman Catholic Church in disseminating hatred of the Jews through its publications such as the authoritative Jesuit journal Civiltà Cattolica is examined. Catholic antipathy towards the Jews fed into and was nourished by political anti-semitism which began to manifest itself in Italy as in other Western European countries. Such incidents as occurred are disclosed and the Jewish response in their press is analysed, thus filling another lacuna in the documentation of this epoch. There is scholarly consensus that anti-semitism had far less impact in Italy than elsewhere in Europe. Nevertheless, it was present in the Liberal party and became integral to the Italian Nationalists’ ideology.

The most international, transformative and cohesive Jewish movement of the late nineteenth century was Zionism. It propelled European Jews into world politics under the charismatic leadership of its founder Theodor Herzl. Il Corriere Israelitico was the first Jewish journal to publicise the Zionist movement to Italian readers. Its unqualified support for the political Zionism of Herzl was in marked contrast to the ambivalent stance of the Federazione Sionistica Italiana, L’Idea Sionistica, and the initial opposition adopted by Il Vessillo Israelitico. The central figures of Italian Zionism, the conflicting ideologies, the internal conflicts, as well as the institutional framework in which Italian Zionism evolved are presented and interpreted within the European context. It is arguably the first time that the English speaking public is offered a detailed analysis of the various Zionist initiatives that were present in Italy.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, in reaction to the prolonged propaganda of patriotism and italianità of the communities’ leaders, the young Jews of Florence began to reassert their ethnic and national identity and reconnect with their Jewish heritage. Their initiatives, such as organizing national conferences, producing their own journal, La Settimana Israelitica, establishing courses in spoken Hebrew, and their impact on Italian Jewry as a whole are the subject of the sixth chapter. This Jewish renaissance was led by the influential and scholarly figure of an East European rabbi, Samuel Hirsch Margulies, who was appointed Chief Rabbi of Florence in 1890 where he remained until his death in 1922.

The conclusion recapitulates the main themes of the preceding chapters, reiterating the similarities between the Italian Jewish experience and that of other European countries, in spite of differences such as the absence of mass immigration from Eastern Europe. Italy has always been on the margins of Jewish historiography, with Germany serving as the pre-eminent paradigm: with regard to assimilation in European Jewish history, one thinks of German Jewry. However, contemporary sources and recent Italian scholarship demonstrate that as individuals and as communities, the Jews of Italy shared the same concerns, tensions and aspirations; they underwent the same complex and multi-faceted transformation as their co-religionists elsewhere. It has been argued that France of the Third Republic is the best available model of real integration of Jews into a state, to which Italy of the Liberal period can be added, producing Europe’s first Jewish prime minister, Luigi Luzzatti, in 1910; France had to wait until 1936 for Léon Blum. No longer can Italy be considered an anomaly within European Jewish history.