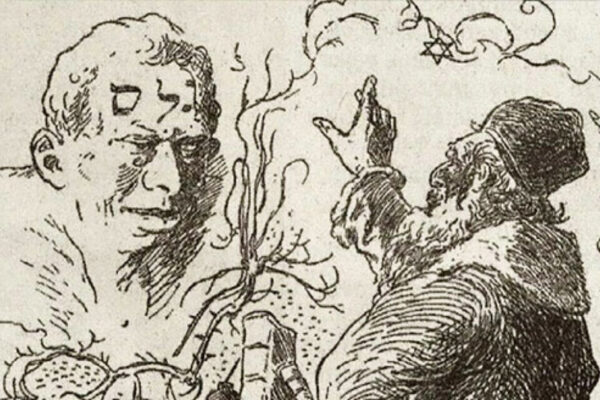

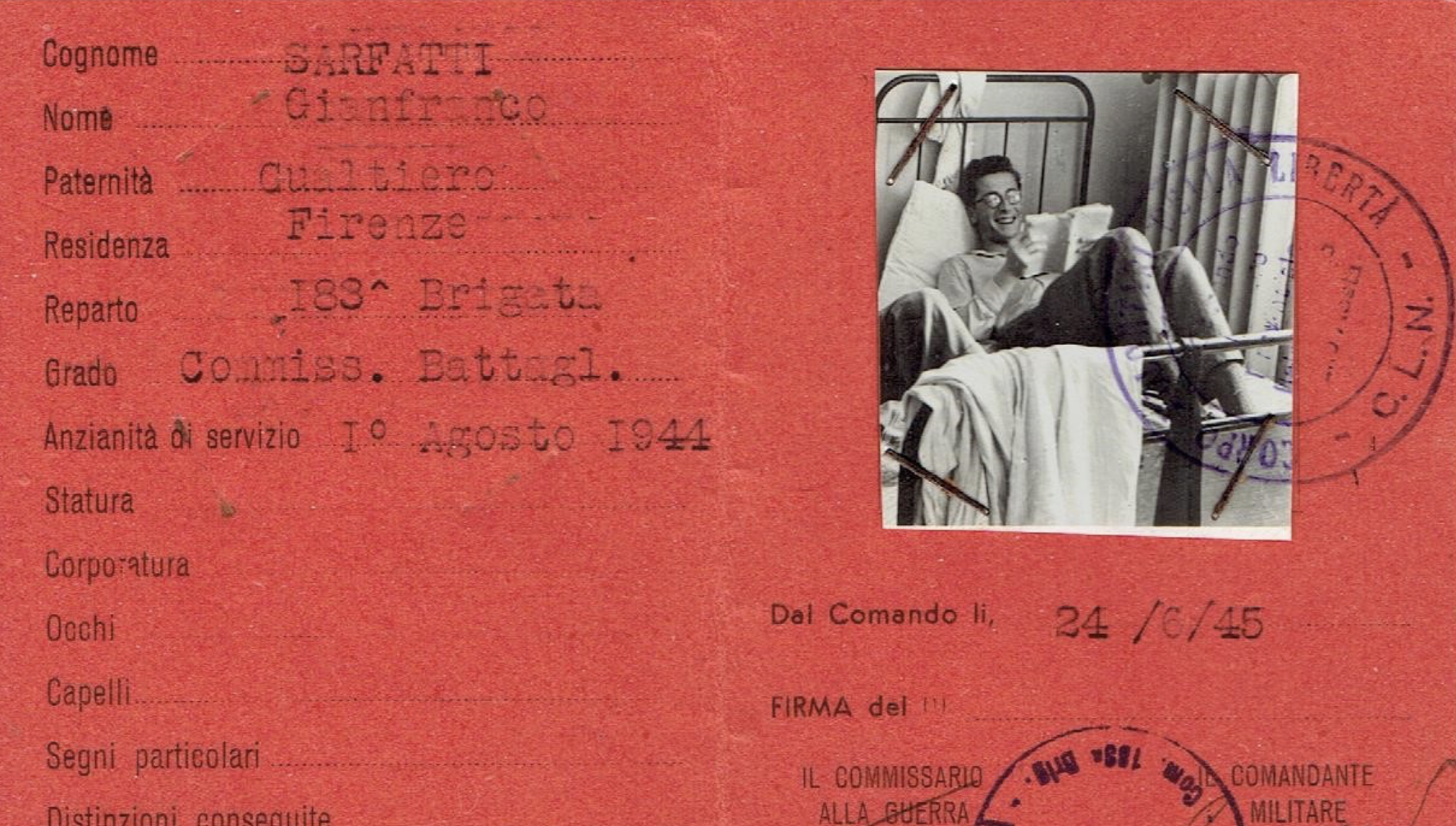

The history of Jewish music in Italy is long, fascinating, and filled with contradictions. Its length is due to the very history of Italian Jewry, whose origins go back more that two thousand years. Fascination stems from the meeting of the music of the Jewish Diaspora, represented in Italy by an unprecedented interaction among distinct Italian, Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions, with Italian musical culture and its innumerable cultural, regional and linguistic differences. The contradictions concern the thousand identities, visible and invisible, of the Jews of Italy: the secrecy of the ghettos, places of exclusion and also of explosive musical ferments emblematically represented in the works of Salamone Rossi (ca. 1570-1630); the conflicts and the hidden consonances between Judaism and Christianity, and the distance between the liturgy of the Church and that of the synagogue, at once brief and unattainable; the integration, and the cultural symbiosis, of Jews and Italy, and the shared feeling so beautifully expressed by Giuseppe Verdi’s Nabucco (1842); the relentless liturgical modernization carried out during the Emancipation in the 19th century, which forever changed the “soundscape” of the Italian synagogue with the addition of choral repertoires and instrumental accompaniment imitating the operatic styles of Gioachino Rossini and others; and the tragic character of the Fascist parable, ended in the Holocaust and the destruction of Italian synagogue life.

Following the Holocaust, Italian Jewish communities large and small have attempted to reconstruct their liturgical repertoires by constantly revisiting the musical structure of synagogue services, by staging public performances of cantors and small choirs, and by releasing commercial recordings featuring historical choral repertoires no longer included in the liturgy. This reconstruction, based on both oral and written sources, highlights the complex dynamics that characterize Jewish musical memory, revealing some intimate aspects of Jewish communal life. Oral sources come from the individual memory of culture bearers, handed down by oral tradition, as well as from the important field recordings made by Italian-Israeli ethnomusicologist Leo Levi (1912-1982), which documented the local traditions of twenty different Italian Jewish communities. Written sources include the transcription of local oral repertoires, most notably those published by Benedetto Marcello (of Venice, 1724-27) Federico Consolo (of Livorno, 1892), Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (of Ferrara, 1936) and Elio Piattelli (of Rome, Piedmont and Florence, 1967, 1986 and 1992), as well as thousands of manuscript music scores. Music manuscripts include 17th- and 18th-century compositions often connected with Kabbalistic representations (in Venice, Casale Monferrato, Pisa and Siena), and thousands of settings of liturgical texts in Hebrew (and at times in Italian) by a host of professional and amateur synagogue composers, Jews and non-Jews alike, kept in Jewish community archives throughout the Peninsula (including Turin, Venice, Padua, Mantua, and Rome), at the Bibliographic Center of UCEI (the Union of Italian Jewish Communities) in Rome and in the Music Department of the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, and in the private homes of Italian Jews in Italy and Israel. The comparison between oral and written sources shows their inter-relations. While many written sources were created to record an ever-changing (or vanishing) oral tradition, original musical compositions often ended up influencing oral repertoires. Oftentimes, the music sung by today’s synagogue cantors in a traditional solo-voice style and perceived by synagogue-goers as “ancient” and “authentic,” is nothing but a “re-traditionalized” memory of 19th-century choral pieces, of which only the main melody (and not the choral parts, at times sung by female or mixed choirs, or the original organ accompaniment) has been preserved in oral form.

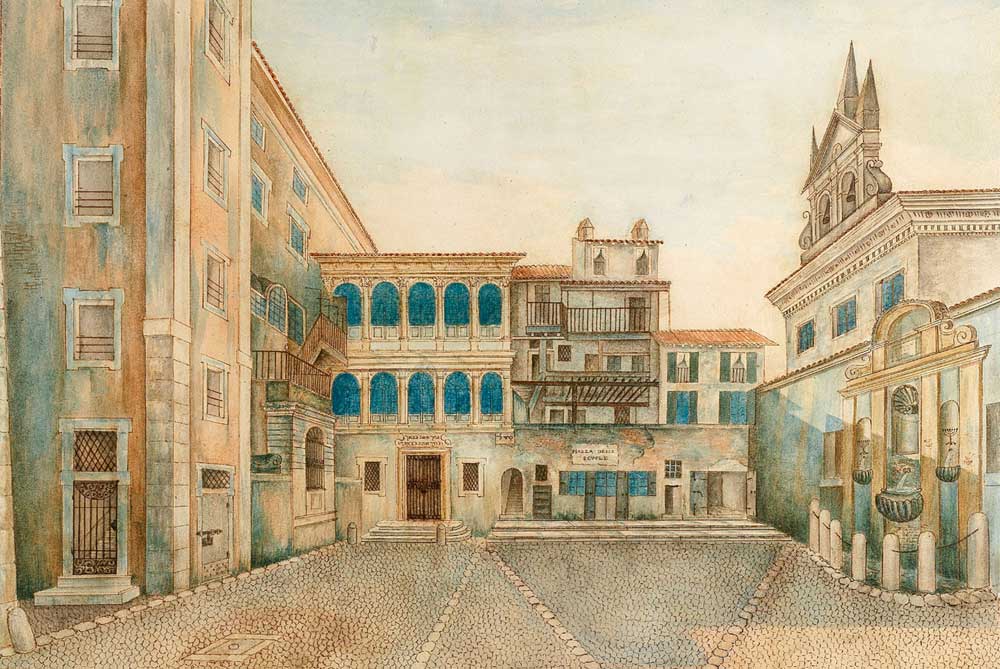

The musical repertoires of the community of Rome represent an emblematic case of interaction among the different layers of Italian Jewish musical memory. The peculiar history of this community is indeed reflected in its music. The traditional soundscape of Roman Jewry was forever changed in 1904, when the inauguration of a new, monumental synagogue (the “Tempio Maggiore”), de facto erased the pre-existing oral traditions kept in the “Cinque Scuole,” the synagogue of the ghetto that preserved the rituals of several congregations according to their geographic origins (including Italy, Sicily, Castile, and Catalunia), by merging them into a unified ritual. The notion of unifying Italy’s diverse Jewish liturgical rituals, an idea that goes back to the advent of Kaballah in 16th-century Venice, had been formulated in a Responsum (1841) by a leading 19th-century modernist Rabbi, Lelio Della Torre (1805-1871), a teacher at the Italian Rabbinical College in Padua. The process had already been tested out in Florence with the inauguration of the monumental synagogue of that city (1882), the merger of local Italian and Sephardic traditions, and the adoption of the Spanish-Portuguese liturgy of Livorno.

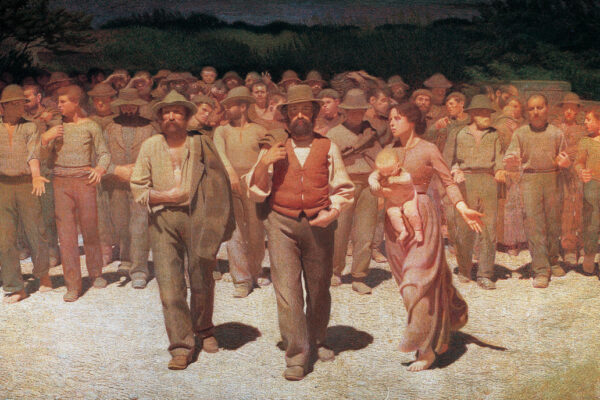

As it had already happened in Florence, the pre-existing oral traditions of the Roman community never completely faded from memory, and have since been kept alive by individual cantors and families, and inserted in the new ritual through the elaborate mixture of musical syncretism and cultural negotiation that characterizes each and every Italian Jewish community. These traditions, however, had not existed unchallenged before the opening of the new Roman synagogue. On the contrary, they had already been sharing the liturgical stage with a new musical repertoire, made of choral music, for at least half a century. This new music was initially imported from other Italian communities, especially Livorno – a thriving center of Jewish cultural innovation, and the birthplace of many of Rome’s “Chief Rabbis” in the 20th century, including David Prato (1882-1951) and Elio Toaff (b. 1915) – from where composers like Michele Bolaffi, David Garzia, and Ernesto Ventura had begun changing Italy’s Jewish sounds since the early 19th century. Starting in 1845, musical composition also became the domain of local composers and choir directors – including Settimio Scazzocchio, Saul Di Capua, Amadio Disegni and Salvatore Saya, among others – whose work was included in the liturgy. Their impact of synagogue music was tremendous, and their work began to be recorded in the Italian Jewish press. A report published in L’Educatore Israelita (a periodical issued in Vercelli, Piedmont), dated 1856, offers a vivid description of how choral music was influencing the culture of the Roman Jewish community, adopting an agenda inspired by modernization and interfaith dialogue (with the Catholic majority), in line with the development of the Jewish Reform movement in northern Italy and throughout Europe.

“In 1845, an association of young men, devoted to the uplifting of the decorum of the liturgy at least on the Sabbath and the major holidays, began studying music so that they could sing as a choir during said holidays, performing the Psalms and other texts. […] Shortly thereafter, three of our synagogues had their choristers trained by distinguished Jewish music teachers. It was also decided to turn these teachers into composers, and they produced excellent works, as heard from Capua, Di Veroli, Disegni, and Scazzocchio.”

Less than a decade later, the modernizing effect of this music had already taken the lead, attracting not only Jews, but also Catholic synagogue-goers. The same periodical thus reported in 1862:

“During the nights of Passover […] our synagogues were full of Catholics, who behaved with the utmost decorum. The synagogue most frequented by Catholics is the Scuola Catalana, since it is embellished by a choir of chosen young men, who truly honored the Festival with religious music, and on the last night [of the Festival] entertained both religious Jews and Catholic visitors with a new Yigdal, set to music by Settimio Scazzocchio, the young director of the choir.”