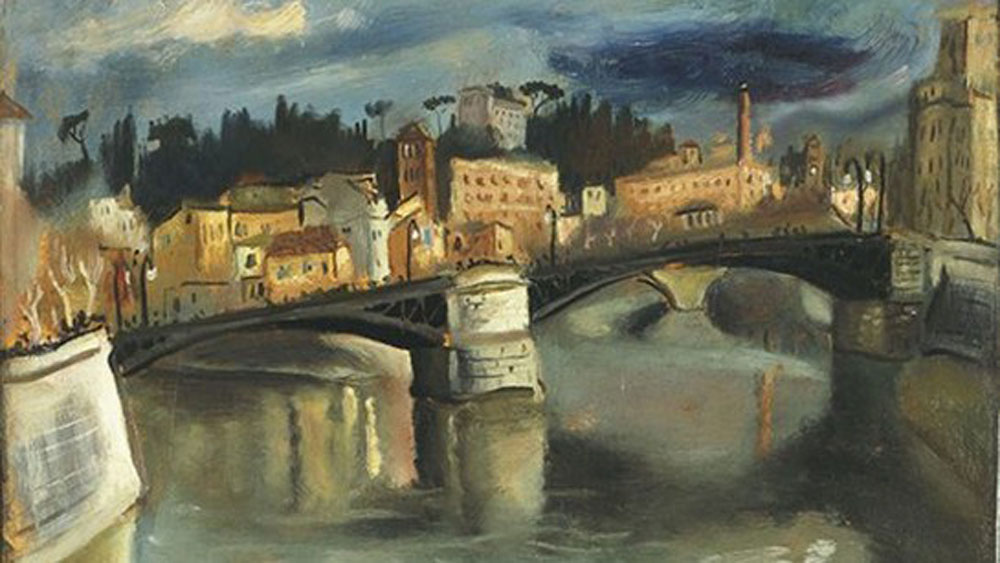

Chapter 2 from Lia Tagliacozzo’s book La Generazione del Deserto, Edizioni Manni, 2021

For 20 years she has been a member of the editorial staff of the Jewish television program Sorgente di Vita (RAI2) and of the Information office of the Union of Italian Jewish Communities. She is a contributor for several publications: the magazine of the Jewish Community of Rome, Shalom, Confronti, and Il Manifesto.

In her work as a writer, Lia Tagliacozzo has focused primarily on books on the Shoah written for children and young adults. These include: “Che storia! La Shoah e il giorno della memoria” EL (2018), “Il mistero della buccia d’arancia,” Einaudi ragazzi (2017), “Inviati per caso – viaggio nell’Italia delle religioni,” a graphic novel illustrated by Eleonora Antonioni, Sinnos edizioni (2016), “Anni spezzati – storie e destini nell’Italia della Shoah” with Lia Frassineti, Giunti Progetti educativi (2009).

Among several documentaries, she co-wrote with Sira Fatucci “Sogni bruciati,” directed by Rebecca Samonà and produced by Vanni Gandolfo (2009).

Translated and edited by Natalia Indrimi and Cynthia Madansky

The boy standing in front of me seems to be taken by surprise. He is just over twenty, younger than my son. When I asked him what he knew about the story of his great-grandfather who was deported and survived Auschwitz, he replied “Everything.” Only the innocence of his age can allow an answer like this. He has never visited Auschwitz and does not expect anything special. “I’ve heard about it, I’ve seen photos, films. Going there won’t add anything.” I envy his candor.

I watch him get off the scooter, he seems so carefree. But I know that is not so. Now that my children have grown up, the urge to see them happy has subsided. I watch them go on as peaceful adults and began to find space for writing. Now that I have done everything I could to save them, I try to keep illegitimate fears deep inside so as not to poison their present.

This is why meeting this young man with glasses, who is even younger than my still young children, was like being given something back. Like seeing an oasis on the desert horizon. [1]

In the biblical desert, the inability to see and distinguish made it necessary for the Lord to open the eyes of Moses. It was only after “opening his eyes” that he showed him the tree that, when thrown into the water, made it drinkable. It is by opening our eyes that we discern the sources of the stories and find the water that help us cross the desert.

In my mind, meeting his great-grandfather, who passed away a few years ago, was like questioning the Sphinx. I thought that he could give me answers, explanations, that he could fill an unbridgeable void.

It was not so. The Sphinx did not respond and History withdrew in silence.

I entered his house in the afternoon of a Roman spring. The first and most striking impression was of surprise. I was there to interview his great-grandfather for an anthology of oral history. He was an Auschwitz survivor and I expected a dark house and a dramatic atmosphere. I was not ready for the light-drenched room and the exuberant vine that climbed all around the large window. Nor was I ready for that generous man whose tragic story unfolded linearly from beginning to end, without reticence or embarrassment. His face like stone, he who almost apologized when a discrete emotion erupted and could not be reigned.

The interview was concluded in the presence of his children and grandchildren —my young friend from the next generation, had not yet been born. Only after hours of reminiscing, when we finally came to bid farewell, I had the courage to ask if he remembered another Roman Jew who was on the train that took him from Fossoli to Auschwitz. A young man of 37, imposing and with dark hair. He was my grandfather. He was on the same train, that departed from Fossoli on April 5th, 1944. I know little or nothing about him. And I knew even less back then, over twenty years ago. I held my breath as he smiled apologetically: “No, I don’t remember.” With that smile, silence fell again on history.

Over the following years, little clues began to accumulate. Letters. Hypothesis. But nobody was ever able to tell me: “I was there. I saw him.”

In spite of my father’s efforts over these past twenty years — when he started talking, inquiring, explaining — no one has ever told me “I know what happened, I know the thoughts and the fear, the fear and the longing.” Traces of my grandfather were lost on the day of November 1944 in Auschwitz, Poland. The Soviets liberated the camp only a few weeks later, on January 27.

Today, thanks to the law that established the International Remembrance Day, (almost) everyone knows the meaning of this date. What they don’t know is that, if my grandfather Arnaldo had only a few more weeks, everything would have been different. Not for the world — for goodness’ sake— but for my grandmother, for my father, and for my uncle. Not to speak of the taboo that made it impossible for my father as a child to leave food on his plate: “If only dad had had it …” Suspended words that spoke volumes. For me too, it would have made a difference: I would have known my grandfather. And not least — as loss passes from generation to generation— it would have been different also for my children who live in the house “with no name on the door.” But this is a long story.

The story begins with Fascism; the Racial Laws; the War; September 8th, 1943; October 16th, 1943; the Military Academy; Regina Coeli; Fossoli; Auschwitz … It is a story that, as I have only recently discovered, has yet to end. Like it or not, the image of the Parisian shop windows that the “yellow vests” spattered with insults against the Jews is contemporary. So are the images of people expelled without humanitarian protection, the dead in the middle of a nameless sea and on mountains without identity. These are stories of today. In spite of the decades that separate them and the obvious differences between an industrialized project of extermination, a violent migration and a racist reception, a thread connects them all. It is a sturdy rope that must be sheared, strand by strand, boy by girl, student by professor, citizen by citizen, men and women. This is a story of death, of wounds, of insults, of dignity, of reclamation; forgotten and then rediscovered; a story of civil memory to be rebuilt each time. Together. This story is made up of many different stories and different people. Because History has many names and each name has a story.

In this story, the name is mine.

My name is Tagliacozzo exactly like the small town in Abruzzo where my ancestors presumably came from. It happened in the early 16th century. The Jews were expelled from the Southern Kingdom and came to Rome, where, in 1555, the bull of Pope Paul IV Carafa confined them to the ghetto. This ghetto was the last to be abolished after the arrival, in 1870, of the Piedmontese army that declared the Pope’s city the capital of Italy. Tagliacozzo is still today a typically Roman Jewish last name and there are many Tagliacozzo families even though we are not all related. With some of them, however, I have visceral friendships and since the children grew up together as cousins, we occasionally bemuse family ties. I have no documents to attest to my family’s life from 1555 onwards, only the voice of my grandmother who claimed that we had been Romans for seven generations. “More Romans than the Romans” she declared. Was it to claim equal citizenship with the “non giudii”[2] as they say in Rome? Grandmother’s words were proffered with affection, irony and only a tinge of irritation as my father had married a Tuscan thus interrupting the Roman lineage. My mother’s last name also recalls a small town in Friuli – Cividalli like the village of Cevedale – but she is part from Florence and part from Ferrara.

I remember certain things of my childhood. Nonna’s shop, the name without an “article,” was invariably that of the Roman grandmother: a haberdashery in the heart of downtown Rome. The spectacular view of Florence’ roofs in my grandparents’ house distinguished my maternal family. The Florentine one was “la nonna”: the “article” was enough to distinguish them. We had only one grandfather, so it was easy and there was no risk of confusion. About the other grandfather, the Roman one, I knew —without traumas or anguish — that “he had been taken away,” that he had “been taken” by the Germans. I don’t remember when these expressions took on the meaning of “he was deported and killed by the Nazis.” It was a natural transition, without rupture. I don’t even remember when I learned about the Shoah. At a certain point I learned about it and that was it.

Paradoxically, at the time, having only one grandfather seemed natural to me. Only twenty years ago I realized that this meant that my father was an orphan. I believe that being an orphan is not a transitory condition that comes to an end when one grows up: my father is still an orphan. My grandmother died when he was an adult and the father of grown-up children: her death was devastating to him but it was in the natural order of things.

Now that I am an adult and a mother, I know that those rare moments when my parents said that grandfather “had been taken away” with no emotional tenor, that it must have come at a cost. It took me years to realize this. It seemed normal then. Yet, at some point, something must have broken my peaceful childhood. Broken is exactly the word. Things get complicated here because my memory, my own, in lower case, not the Memory of the Shoah with capital letters, can no longer find precise points of reference. I know for sure what happened during one day of my teenage years on a cliff of a Sicilian island. But between then and today I have written and talked about it so much that the memory is no longer that of what happened but that of what I wrote and told boys and girls, students in so many schools in Italy. When I realized this, I felt liberated: the impalpable yet resistant substance, intuitive but impossible to circumscribe has finally defined its consistency in writing. It was as if the ghosts of the past had finally taken shape and quieted down. There is a lot to be said about the fact that this act of writing was always intended for children and teenagers. For many years, I have written for newspapers, magazines and television but when I started writing books, they were for youth. And they were books on the Shoah. The story, at least partially expunged of the horror, was told to young people. The choice of words and the structure of the events were intended for them. And they were all “true stories.” Tales of men and women with names and last names, sometimes even with numbers tattooed on their arms. It is as if imagination cannot extend beyond reality. The Shoah has millions of names and stories, there is no need to invent others. Inside those pages there is also the story of my family: paternal and maternal. With writing, fears have found a place to rest and words to be shared.

Something began to surface in my conscience long before the revelation on the cliff. Evoking it and pinning it down is like opening a Pandora’s box that comes with a persistent and bitter woodworm.

My children and I belong to the generations of those “who came after.” We are the last to hear this History, in capital letter, directly from the witnesses. The last to listen to the memory of individuals, to their voices, to human beings who witnessed first hand what mankind can do to mankind. We are the last ones, bracketed between often secret and unspoken private memory and the memory mediated by study and institutions. We are today’s adult sons and daughters of those who have suffered this history as children and those children’s grandchildren.

In my family, my father’s story looms heavily. It loomed through silence and words. So much silence first and then so many words, which, in turn, hid more silence. Mother’s story on the other hand seemed to have deserved fewer words altogether. As a child, she hid in the mountains and found safe heaven in a Swiss internment camp. After being separated from her family, she was entrusted with payment to the care of an unknown peasant family. Sometimes I think that my books for boys and girls had the ambition — narcissistic and boundless — to lift the responsibility of the story from their shoulders, and restore serenity in their words for their grandchildren. Obviously it did not work out this way. But the illusion was justified, being one more effect of the conspiracy of silence.

In my family the wartime stories have always been kept quiet. Throughout my childhood and early adulthood, reconstructing them entailed years of occasional discoveries, of haphazard clues, of diving clandestinely into family papers. It was long, solitary work, conducted without the comfort of exchange with my sister and brother: each one of us has embarked in this excavation according to personal inclination and different degrees of urgency of questions and answers.

Here is the story of my family, that is also my story, the pursuit of the truth and the discoveries that have constantly accompanied me.

Nonna Eleonora, whom I was named after, has always been old, which makes sense as she was my father’s grandmother. In a rare family photograph she appears as a little old woman dressed in dark clothing. A cousin of my father remembers her bent over from grief from losing her 20-year-old son in a motorcycle accident. Nonno Davide, my great-grandfather, was big and fat. I don’t know anything else, except that he died in the first years of the war. They lived in an Umbertine house just outside the Aurelian walls. They were the kind of people whom in Rome are called “casa e bottega.” Negozio, the shop, (strictly Roman-style and without the article) was located a few hundred meters from the house: a large store, on a beautiful street. They were tailors and fabric sellers in the true tradition of Roman Jews. It was a family business, run by nonno and his brothers. Even before the war the “head of the house” was uncle Amedeo.

I live in the apartment next to my great-grandparents’, on the same floor, but — speaking of silence — I have never known the exact address of that store. Strangely enough, thirty years ago, I took a taxi from the central train station and gave my home address. The taxi driver, polite and in a talkative mood, told me that he knew the area because as a young man, he had worked there in a tailor shop. My antennas started vibrating: tailor? In that street? Continuing the conversation on the Muro Torto, it comes up that my name is Tagliacozzo. The driver sighed: “Whose daughter are you? Fernando’s? I worked in their shop when I was young. Signor Amedeo was a stern but righteous man, he was in charge.” He didn’t say anything in particular about my grandfather or perhaps I forgot what he said. I don’t remember the name of the taxi driver either, maybe Walter. Yet I am deeply grateful to him: he added a piece to my puzzle and confirmed that, beyond a few family allusions, the shop and “life before” had really existed.

Of my grandfather I know that he played soccer and that — to my son’s great chagrin — he was a Lazio fan. I also know that he occasionally left the house to go buy cigarettes and that sometimes he returned home later than expected. I know that, even if there were no photos of him on the walls of the house, I was able to recognize him: tall, dark, with my uncle’s same imposing nose that I too have inherited.

In those years, I was gathering clues about the history of my family’s “life before” without knowing that those clues would soon be pressing upon me for answers. I was a curious child, growing up, learning at my own pace. The stories I learned from outside the home were separate from what had happened to my family. Nonna (the Roman one, without the article) had a haberdashery in the historic district. It was not the pre-war tailor shop but a shop that sold buttons, threads, underpants and stockings of all kinds before lingerie became fashionable. I used to go there as a child and still remember the magic of small drawers with spools of thread: it was a symphony of colors that dissolved one into the other without interruption. My eye glanced over the reds into the oranges and then the yellows unable to seize the moment in which the color changed. I repeated the game several times, shifting my gaze slowly, but it was impossible to find the point of separation. Perhaps my dislike for fences and delineations of differences comes from this childhood game.

From what I remember, I used to go to the shop quite often: I helped with gift wrapping, run small errands on the block (always without crossing the street). Only when I was older was I authorized to touch the drawer where the money was kept, which was long before the cash register became mandatory. At this time, I kept collecting clues with the attention of a curious little girl. One day I was with nonna on the bus, returning home from the shop. People could smoke on the bus back then and nonna, seeing the conductors entering at the same time from the front and back doors, turned pale. She angrily crushed the cigarette on the ground, while sweat began to cover her upper lip. I looked at her, frightened. She was a strong and solar woman with commanding features. She looked like an Ethiopian queen. I had never seen her so upset. The explanation came shortly after. It was not addressed to me, but to someone else on the bus: “It reminds me of the war,” she said casually, “when the SS entered buses like this and checked documents.” At that point her discomfort seemed obvious to me. Even as a child, I understood that having spent months walking the streets with a false identity card was enough to justify her distress. I held my breath and waited but — as so many other times — no other explanations followed.

In those years I collected other small fragments of the past. One episode probably dated back to the war years but before September 8th. The family went out for a joyful evening together. It must have been a special moment because grandmother remembered it with unusual cheer: in a rotisserie they had found supplì (rice croquettes) — something unusual in wartime — and had bought some for the children. My father, however, let his supplì fall on the ground. Suddenly a poor child appeared — at least so she appears in my memories. She kneeled down, picked up the food and voraciously put it in her mouth. My grandmother wanted to explain to me how severe hunger was in Rome during the war. I remember that I was bewildered at the story: on the one hand I felt relief for the fact that they could buy a supplì, whichmeant that they had not suffered from hunger and that the poor child was hungrier than them. On the other, I was perplexed because, as a child, I imagined their situation similar to that of death camps that I must have seen in some photos. This kind of chronological and emotional asynchronicity pervades the history of my family along with my discovery of it.

Again on the subject of photographs, I remember with shivers the first time I remained home alone and discovered some photos of the “life before.” I was still a child: my mother went out with my sister and brother. There was no need for her to reiterate that the small writing desk should not be touched. That was absolutely off-limits: we were strictly forbidden to browse in the cabinet and its mysterious hiding places. The prohibition came with no explanations. It contained “mom’s and dad’s stuff” and that should suffice. What that might be, was at the time a fascinating secret intended to safeguard adulthood. Maybe it was on that day that something shattered my childhood. But now it is easy to attribute a meaning to that childhood adventure as I know the ending. As soon as my mother left, just long enough to hear the elevator click, I threw myself on the forbidden cabinet. Wonderful things began to appear: stained glasses as small as a thimble; a broken doll in a pink dress; small silver and pewter objects; a statuette of Murano glass. And then, naturally, papers: hand and typewritten letters, time-worn thin tissue paper, thick sheets of diplomatic paper, documents of all kinds, and some black and white photographs. One slipped haphazardly off the pile: a photo taken on the roof of grandma’s apartment building — the same place where I live. The old woman dressed in dark could only be grandmother Eleonora; the man with an imposing nose was certainly my grandfather. I had never seen his photograph but I was sure it was him. He embraced two children and a girl. I easily recognized the two boys: my father with his mischievous smile, and my uncle, more serious and composed. The little girl, on the other hand, I could not imagine who she could be. Grandpa Arnaldo’s arm was equally protective of the three but I had never heard of her: no cousin, relative, friend or neighbor had ever appeared in family stories. The jingle of the keys in the door abruptly interrupted my reflections. With fear of being caught, I crammed everything into the cabinet.

No one knows what dramatic consequences might have occurred from transgressing that one true prohibition my parents had imposed. The problem with doing things secretly, however, is that one cannot ask for explanations: who that little girl was became a tender curiosity that accompanied my youth.

The most beautiful and exciting wartime story, of which I was immensely proud, was about a mysterious partisan fighter my grandmother knew. After my grandfather’s arrest and deportation, she sought to collaborate with the Resistance, and got in touch with him. He refused to draft her and told her: “You have remained alone with two small children. Forget it. It is too risky. Think about raising your children as free Italians. This is your contribution.” My grandmother, apparently reluctantly, accepted and limited herself, to occasionally delivering false identity cards. The story, however, had a sequel after June 4th, 1944, when the Anglo-Americans liberated Rome. But to get to that, I must first go back in time.

It was the autumn of 1938 and the Racial Laws had come into force: starting from the first days of September, Jews were progressively excluded from schools and workplaces. First the laws targeted foreign Jews who were expelled from Italy. Then, students were turned away from all the schools in the Kingdom. Teachers and professors were also removed. Among them was my grandmother Lina, one of many elementary school teachers. The letter of dismissal came two days after my father’s birth, in December 1938. Grandmother too came from a family of merchants, also of fabrics. Their shop was on via Ripetta, behind piazza del Popolo. Before getting married, she lived there with her mother and her blind sister Titti. Her father, Grandpa Pacifico, had died shortly before this time. “Fortunately,” my grandmother used to say, “he didn’t see what happened next.” Grandmother taught at the Jewish school.

I have no idea what happened in those years to the tailor’s shop in via Salaria. In the meantime, the Jews continued to be excluded from other workplaces. Their life was subjected to an increasing list of prohibitions that continued to grow year after year: it was forbidden to own a radio, to go to the beach. One could think that these are laughable prohibitions. But it was in this way that the Jews were excluded from civil society, became second-class citizens, eventually legitimizing what came next. The legislation was so pervasive that once the war was over, its abolition took decades, as the new political class of democratic Italy were complacent. The latest abrogative measures were not completed until the 1980s.

I don’t think there are wedding photos of nonna Lina and nonno Arnaldo. For me, their life begins together in the Umbertine apartment on the consular street, on the same floor as nonna Eleonora and uncle Amedeo, grandfather’s bachelor brother. For sure they got married before December 1935. I know this for a fact because after Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia and the sanctions of the League of Nations, Mussolini launched a campaign to collect gold for the fatherland. Everyone mobilized: to support the costs of the colonial war, the King donated gold, Luigi Pirandello his Nobel Prize medal, ordinary people did what they could and the women donated their wedding rings. More than 250,000 rings were collected in Rome alone, about 180,000 in Milan. However, my grandmother —even though she was a member of the Fascist Party (I discovered this with unjustified embarrassment when I cleared out her house)— must have harbored misgivings. On that same bus that took us home, while glancing at Villa Borghese’s railings that had been used to make armaments and were rebuilt after the war, she told me: “I did not give my wedding ring to Mussolini. I kept it. I didn’t want the iron they gave in exchange.” She said it proudly. Indeed, the wedding ring has remained with her much longer than my grandfather’s company.

As horrors unfolded, family voices went silent: dates that I learned with unusual ease from books form a timeline with no family anecdotes or memories. Silence has run its course.

I do not know how this middle class family of Roman Jews reacted watching Italy drawing closer to Germany. Or if, on January 19, 1939, they took notice of the abolition of the Chamber of Deputies which was replaced by the Chamber of Fasci and Corporations. Or if they were aware that nothing had remained of the pre-Fascist institutions and that members of the Senate were selected by Mussolini and ratified by the King. I don’t know if, in May 1939, they went to the movies and saw the newsreel announcing the Pact of Steel between Italy and Germany. I don’t know any of this. I don’t know if they were alarmed seeing images in the press of the Germans crossing the border into Poland on September 1, 1939: it was the beginning of the Second World War. I don’t know if they had any premonitions.

What I know is that my grandmother taught me early on what “the balcony” was. In Rome, at least until my generation, everyone knows what it is: Mussolini’s balcony at palazzo Venezia from which the dictator addressed the crowd. For most people, except for the fascists, “the balcony” is just a meeting point. I don’t know where my family was on June 10, 1940 when the Duce thundered from the balcony: “Fighters of land, sea and air! Blackshirts of the revolution and of the legions. Men and women of Italy, of the Empire and of the Kingdom of Albania: Listen! The hour destined by fate is sounding for us. The hour of irrevocable decision has come”.

“Irrevocable” he said, just like in September 1938, from a similar balcony in Trieste, he had said that the Jews “are an irreconcilable enemy of fascism.” He must have liked the prefix “irr” quite a lot. The majority of Jews received the proclamation of 1938 with candid astonishment. Until that moment, they had considered themselves citizens like all others. Those who were anti-fascists, perhaps a slightly higher percentage than the rest of the population but still a minority, were dissenters by virtue of their political conscience, not of their being Jewish.

On June 10th, 1940 the Duce changed the destiny of the entire country: “The declaration of war has already been delivered to the ambassadors of Great Britain and France. Let’s take the field against the plutocratic and reactionary democracies of the West that have always hindered the march, and often undermined the very existence of the Italian people.”

Until a few years ago these expressions seemed outdated, remnant of an aggressive and obsolete language, but today they resound disquietingly new amongst us. Since the Jews had been expelled from the army, the declaration of war might have worried them at most as second-class Italians but none of them would have been drafted.

In the meantime, uncle Davide, two years my father’s elder, had entered first grade. His report card, issued in the twenty-first year of the Fascist era, states: “of the Jewish race,” beautifully handwritten in red ink. The expulsion from school left unhealed wounds. One of my maternal aunts, who has lived in Israel for decades, still remembers her anger at that estrangement. Still today, even if a bit confused because of her age, she is adamant that she does not want to go back to the country that kicked her out of school.

The fall of Fascism, on July 25th, 1943, bursted with cries of joy in a lightless Rome. It is exactly near my house, the same one as my grandparents, in the park where we walk our dogs, today known as the Villa Ada, at the time the Villa Savoia, that, after the pronouncement of the Grand Council of Fascism, the King summoned Mussolini. There, he was arrested. I was unable to reconstruct whether the place of his first imprisonment, the Carabinieri School of Rome, was the same in which a few months later 2,500 carabinieri were imprisoned by the Nazis before been deported. Their deportation was organized just before the raid of the Jews of Rome perhaps out of fear that they could stand between them and the Jews.[3]

On July 25th, 1943 the government kept the news strictly confidential throughout the day. Only at 10:45 pm the radio interrupted the broadcast to give the announcement: “His Majesty the King and Emperor has accepted the resignation from the office of His Excellency the Knight Benito Mussolini, Head of Government, Prime Minister, and Secretary of State. He has appointed the Knight, Marshal of Italy, Pietro Badoglio as Head of Government, Prime Minister, and Secretary of State”.

Upon hearing the news, the Roman population poured into the squares and the streets invoking peace and freedom. But the crowd’s cheering ceased after Badoglio’s announcement: “The war continues. After severe blows in its occupied provinces and in its destroyed cities, a jealous keeper of its millenary traditions, Italy maintains its word.” Some say that this was done to avoid alarming the Germans. But for all Italians it was like a cold shower. In that summer of 1943 the Jews of Rome did not know that, in that spring, during the days of Passover, on April 19 of the secular calendar and on the 14th day of the Jewish month of Nisan, the uprise of the Warsaw ghetto had begun. It lasted a month. At that time the ghetto was liquidated and thousands of people were killed. Those young insurgents claimed for themselves the most terrible of rights: they chose to die fighting and not become victims in the extermination camps and the gas chambers. In that summer of Roman joy, everything had already happened, but my family at the time did not even suspect it. They did not know how criminal the extermination project that awaited them was. Today, kept as a precious object in my parents’ folding desk, a soap dish, poorly covered with a layer of silver, is engraved with the date of the Warsaw ghetto uprising. It was brought from Poland by our dear friend Fabio. Nobody knows its origin, or what it means. For us in the family, a strange thread connects the Warsaw ghetto and mountain songs to that engraved soap dish that comes from afar: it is the instinct of fighting, of claiming one’s dignity, the indelible sense that, despite Nazism and Fascism, our story did not end in those years. It means that the children, and the children of our children, today play, have fun and live. And they celebrate Jewish ceremonies, they study and testify to the vitality of Judaism. We are not, as Hitler wanted, “an extinct race.” The memory of what happened is the legacy of our freedom. Not just past, but present and future. It is a warning to act and protect the values of democracy precisely because the story did not end then. In our family, at the Seder—the Passover dinner—it is customary to read the “ritual of remembrance.” In recalling the coincidence of the dates in Warsaw, the Haggadà [4] states: “But we abstain from dwelling on the deeds of the evil ones lest we defame the divine image in which man was created.” [5]

Hence the summer of 1943 also passed There are no letters, diaries or memories that have preserved a trace of it. I only studied the events of September 8th in Rome in history books. Only one echo vibrated through the house: Porta San Paolo.

“On September 8, 1943, the government announced the armistice of Cassibile by which Italy, up to that moment Germany’s ally, surrendered to the Allies. The Royal family, the new head of government Marshal Badoglio, and the high commanders fled to safety in Puglia. The Germans quickly completed the occupation of four fifths of the country and prepared for the creation of the neo-fascist Republic of Salò.”[6] The armistice was actually signed on September 3 but it took a few days for it to become public. In 2008, at Ortona, a plaque commemorating the King’s escape was restored: “On the night of September 9th, 1943, from this port, the last King of Italy fled with the court and Badoglio, handing his tormented homeland over to German anger. Republican Ortona from its rubble and wounds cries an eternal curse to the monarchy, its betrayals, fascism, and the ruin of Italy, demanding historical justice in the holy name of the Republic.” The original plaque was dated September 9th, 1945 when the rubbles of the war were still there for everyone to see.

The city found itself at the center of the conflict on the Adriatic side: bombed by the Allies and devastated by the Germans. The two armies fought in the streets and among the houses of the city. On that plaque is the language of a battered people.

Some sources say that in Rome, on the day before this happened the shops were closed and the markets deserted. Yet, between the 9th and 10th of September, a man called Ricciotti, a fruit seller, after ending his shift at the central market, refashioned himself as an exceptional shooter. He died at Porta San Paolo. There, the Resistance rose, unexpectedly: soldiers and civilians, men and women kept the German army at bay for hours. 400 civilians died, among them 43 women. But they lost. And so for Rome and my family came the dark months of the Nazi occupation. In my house, however, I don’t know why, Porta San Paolo still means courage.

Resistance also came from the Italian military internees, the soldiers fighting in Kefalonia, the people of Naples’ famed “quattro giornate.” (Four days of Naples) (either translate or put footnote) Between September 27th and 30th, 1943, a popular uprising, flanked by soldiers who had remained loyal to the Southern Kingdom liberated Naples. It was the first major European city freed from the Nazis. On the 1st of October, exasperated and exhausted, Naples welcomed the arrival of the Allies as a free city.

Who knows if nonno Arnaldo and nonna Lina understood what was happening. The Resistance began during the same days in which the Italian Jews became afraid. In Rome, the majority of the Jews did not understand, only a few seemed to have had an inkling of the disaster that quite obviously was about to unfold.

Some people were more cautious: the Modigliani family decided to stay in Morice, near Velletri: “My parents,” says Enrico, “in the confusion of those days preferred not to return to Rome and wait on the Castles hills to see what would happen.” Many grasped the uncertainty of the future but few understood the risks [7]. The Tagliacozzo family certainly did not understand: they spent the summer in Poli, at the house of Peppina, the housekeeper. Probably they wanted to keep the children away from the unrest and the allied bombings that on July 9th, had devastated the district of San Lorenzo near the Termini station, the same area of their Umbertine home.

At the end of the summer, however, they returned to Rome. In hindsight, the warning signs were there but hindsight notoriously paves the way to hell, certainly not just metaphorically.

Silence pervades family history during those crucial months. Not even the furious lucidity of my father is able to reconstruct them. Today, he speaks to teachers and students all over Italy trying to explain an incomprehensible world.

For the Jews of Rome, September 1943 precipitated through convulsive and premonitory days. No matter how many books I read or how many essays I consult, I can’t find the story of my family. I do not find it because history does not tell what happened the routine of getting up and going to work, it does not tell about children’s quarrels on a late summer day when the light of Rome turns orange and the evening brings fresh air from the sea. It does not tell about the hardship of trying to buy food. History is not about us. The gaps remain such and those who cross the desert with illegitimate curiosity cannot but fail to ask direct questions: to fill the gaps of the story, and they put their imagination to work. When this happens, they feel as if they are betraying the truth. For us, crossing the desert is difficult because there is no starting point. It was drowned in the pain of a non-story.

And thus it is impossible to imagine what the arrival point might be. The wedding ring on my grandmother’s finger that she testified, thirty years later, that she did not give in to the blackmail for gold. I try to imagine that she felt no guilt: it was a blackmail, what happened next irrefutably demonstrates it. Her wedding ring and her gold would have not stopped the Nazis.

In a report dated November 15th, 1943 and published several times, Ugo Foà, then president of the Jewish Community of Rome wrote [8]: “Between September 8th and 26th, although the Germans had all the power concentrated in their hands, the Roman Israelites had not been harassed. On the contrary, hope began to emerge in their hearts that the excess that their brothers of the same faith had been victims to in the other countries previously invaded by the German armies, would not repeat itself in Rome.” Until then, the Jews “tried not to offer a pretext for persecution.” But despite their effort to walk close to the walls, not to be seen, not to attract attention, as if just being alive would give the occupiers the right to decide the fate of their life, the Roman Jews were eventually deceived. Yet, they gave their trust. They trusted twice. The first was on the 26th of September when 50 kilos of gold were extorted from them. In those hectic and agitated hours, the German Embassy summoned the president of the Jewish Community of Rome Ugo Foà, “former Deputy Attorney General of the King,” and the president of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities Dante Almansi, “former Prefect of the Kingdom.” All these titles and positions however did not put them on guard: “We will not take your lives or your children if you fulfill our requests,” SS Major Herbert Kappler told them. His demeanor did not arouse any suspicion in them. “It is your gold we want. We need new weapons for our country. Within 36 hours you will have to deliver 50 kilos. If you comply, you will not be harmed. Otherwise 200 men will be taken and deported to Germany at the Russian border or will be otherwise rendered harmless.” The Jews gave in to the blackmail and trusted the promise. The news spread around the city: people came to give their most precious objects: chains, bracelets, small jewelry. Those who were able to, offered more. Someone donated money. Not only did the Jews participate in this hateful collection, many unknown Romans went to the offices of the Jewish community at the synagogue, on the Lungotevere. Many members of the clergy. Among them was Romolo Balzani, a famous Roman singer of the time. Balzani’s visit to donate a family ring remained indelibly impressed in the memory of many Jews who were there. Leaving the community offices he began to sing on the stairs: “Credi che chi c’ha l’oro sia ’n signore, l’oro per me nun conta, conta er core” (You believe that gold makes people noble, but gold does not count for me, what counts is the heart), the refrain of Passione Romana. The Vatican too informed the community that in case of need it would have added the missing weight. The Pope however, made a good impression but did nothing: the goal was reached and the gold delivered. In spite of the reputation of Teutonic correctness, the Nazis tried to cheat on the weight but, in the end, the transaction was concluded. Roman Jews breathed a sigh of relief. I wonder if anyone recited the HaGomel, the blessing for dangers averted. It would have been a tragic mistake. Yet they trusted.

I don’t know if my family contributed to the gold drive. We did not find the receipt that was given to those who gave the gold, but so many documents were lost, so this doesn’t mean anything. Surely grandmother Lina, for the second time in her life, refused to part with her wedding ring. She was right this time too. The day after the gold was delivered, some Nazis showed up at the community office. In his report Foà states that they did not find the membership lists because they had already been taken elsewhere. The search in the offices on the Lungotevere went on for days, including in the presence of Nazi officers who were experienced hebraists. On the 13th of October, two important historical libraries were taken away: the library of the Jewish Community of Rome and that of the Rabbinical College. “Manuscripts, incunabula, soncinati, 16th century oriental prints,” Foà writes, “unique Hebrew books, numerous and important documents concerning Jewish communal life in Papal Rome from the early days of Christianity up to 1870.” “Once the wagons were loaded,” Foà painfully continues, “they were carefully sealed and shipped to Germany.” We could not do anything else but record the number and destination of the wagons: DRP – Munchen – 97970 G and DRPI – Munchen 97970 C. The library of the Rabbinical College was only partially found after the war, but that of the Jewish Community of Rome left no trace. Decades later, a government commission tried to reconstruct its journey to no avail. A few years ago, at a conference in Hanover, Germany, one of the books was returned to the representatives of the commission. I am deeply moved by the thought of this precious missing library. Lost lives, people who disappeared up North, cannot be reclaimed, but finding those books would represent a small reparation. Not for their absolute value but for their relative value: for the hours of study spent on those pages by generations of Jews, for the answers to the questions that so many have looked for in those texts, for the lives and fingers that have leafed through their pages.

What happened to my family in those days? What did they know about what was happening? What did they understand? Were they afraid or reassured by the German promise that no one would be touched thanks to 50 kilos of gold? Did the children still attend the Jewish school? Did grandma continue to teach? Was the shop still open? Family anecdotes precede the events of October 16th: dad’s cousin remembers that the tailor shop served the Russian diplomats and that, departing from Rome, they left sugar and coffee to the Tagliacozzos [9]. It is difficult to reconstruct when to place the episode. My father, on the other hand, remembers a written note concerning the fulfillment of an order of “excellent” collars. Instead of being understood as a reminder, the note was interpreted as an acknowledgment of the shop’s good work and a statement of sympathy toward the persecuted Jews. These tiny signs are ripples in the sea of what I don’t know. They are utterly insignificant details that nevertheless give body and substance to that “before” of which I feel the void.

A few days passed between the blackmail of the gold and the loot of the libraries. Both events happened after the Jewish holidays. Maybe my grandparents also breathed a sigh of relief and trusted the Nazis.

Continuing to use the words “Nazis” is a hideous effort to be politically correct: no-one at home ever said “the Nazis,” they were always and only “the Germans.” Only much later, in my adult life and after I became a mother, it happened that for decades my son had a very close friend named Moritz. In their kindergarten class—the school was in the Umbertine neighborhood where we lived— they both stood out: one Jewish and the other German. Perhaps it was inevitable that they became friends. Only later did we realize that it was a strange twist. I can’t remember the exact date, but the memory is still crystal-clear: one day during the elementary school years, I went to pick up my son at Moritz’s house and rang the intercom.

I was going to bring him to Hebrew class. Moritz answered: “no way — he stated resolutely — how can his best friend study Hebrew and not him, what the heck!” His logic was unquestionable, the cultural and emotional responsiveness of his parents too. So it was that, for a few years, the two of them took Hebrew classes together: language, history, and culture. When the time came for Daniele to prepare for the rite of passage, the bar mitzva, Moritz quit. Who knows what he remembers of those afternoon classes. Since then, however, for intellectual clarity, I felt it was only right to make the distinction: the Germans are Germans and the Nazis were Nazis.

A few years later in middle school, the kids were studying the Second World War together. For Moritz the Germans had unleashed the Second World War and built the extermination camps. I pedantically interjected: “It was not the Germans but the Nazis.” They both answered in synchrony and disdainfully: “All Germans were Nazis back then,” thus placing a stone on my politically correct efforts. Yet, since I have begun to speak to school students about the Shoah, I make a point to distinguish between Germans and Nazis, even if I stumble on my lips. It is a way to place history in the past.

October 16th, 1943 is an unforgettable date. Roman Jews of the generation of the desert know some things with absolute certainty. They absorbed them through their mother’s milk, words, and silence: it was Saturday; it was dawn; there was the distribution of cigarettes; it was drizzling. All other images and stories find their way into this grid of insignificant details. I believe these details help make ghosts real: 1,020 Roman Jews were deported on that day. Only 15 men returned, one woman and no children.

I learned about what happened in the hallway of my grandparents’ house when I was sixteen. It was the middle of the summer and while lying on a cliff on an island, I overheard a conversation.

The sun was scorching, the memory still is.

My mother and her best friend Paola, sat a few meters above me and talked. They have been friends since college, and her son and I have known each other since before we were born. He was in the water as boys do, and I was sunbathing as girls do. I remember the sun on my skin, the little dot in my cornea that I only notice when I stare at the sky. I enjoy chasing it with my eyes without ever reaching it. In the cove of blue water no one was listening and the whispers of my mother and her friend dissolved in the air. Their intimacy goes back to their youth. Absorbed in their conversation, they did not pay attention to me lying in the sun. They mentioned something that they have already talked about in the past, mom only hints at it because Paola already knows what it is. Not I. I knew that October 16th, 1943 was for Roman Jews “the date.” But I couldn’t imagine the rest.

Two Tagliacozzo families lived on the third floor of the Umbertine apartment building on the consular road. One consisted of my great-grandmother Eleonora and uncle Amedeo, who had remained a bachelor. He was the eldest of a series of stillborn and unweaned babies that ended after Eleonora had a dream: an elderly relative prompted her to change the name of the unborn child and no longer call him Amadio. Grandmother Eleonora acquiesced and all children that followed survived. When grandmother Lina was expecting my father, a cousin appeared to her in a dream and spoke about the child in her womb. The cousin’s name was Fernando and therefore my father was called Fernando. He survived weaning as well as the industrialized extermination project that wanted him dead. For this reason, this family of engineers and biologists with a strong positivist and rational mindset, still harbor a discreet respect for dreams.

In the wake of the new millennium, I was in the first weeks of pregnancy. Unaware of the consequences, my husband candidly mentioned that he had dreamed that we would have a baby girl and that she would be called Alessandra. In spite of the professional background and rational nature of my partner, when the ultrasound confirmed that we were expecting a girl, I told him about the family dreams and, to be on the safe side, our daughter was called Alessandra. The only mediation I accepted was that it would be her middle name.

I am procrastinating telling, line by line, the story I heard that day under the sun. It did not illuminate anything, did not explain anything but a slit, window opened. Only after many years do I understand that the conspiracy of silence that my family has unconsciously woven around my generation was a defense mechanism. Even when I did not know but sensed that I should not ask questions, I was still aware, deep inside me, that it was an expression of love. The conspiracy of silence is in fact an act of mutual love: of the parents for the children and of the children towards the parents. A pact for mutual protection, the expression of an unspoken yet evident love. The explanation was tragically simple. I discovered it that day on the island: the other Tagliacozzo family living across the hallway of the Umbertine building, included nonna Lina, nonno Arnaldo, uncle Davide, dad and Ada, their big sister: a little girl of eight who would have become my aunt but whose existence, until then, I completely ignored. She was the child in the photo: not a neighbor, not a distant cousin, not a playmate. She was dad’s sister, three years his elder. Ada was born on January 23rd, 1935. My sister’s daughter was born on January 24 and I on January 25. Three women, three generations, one date after another. It is not a dream, perhaps it is a sign.

Our unspoken family account does not say what happened in those hours. The story I tell today is probably different from the one heard on the island. Most likely, it contains some attempts to fill the gaps. Since then, however, after many years and one generation, the conspiracy of silence has been broken. My children and nieces were loved with words. Even if they came too soon and may have violated their innocence.

To be able to make peace with the silence that surrounded Ada, I had to fill the gaps in the story: “A rupture in historical continuity,” writes Andrea Smorti, “pushes us to try to fill this ‘void'”. On the other hand, he continues “the narrative produces a framework that makes all these absurdities plausible within a certain type of world. […] Some narratives become so persuasive that they inform people’s lives, so much so that Marquez could write that life is not what you lived, but what you remember and how you remember it in order to tell it.” Today, many years after that first revelation, it is impossible, and in any case painful, to reconstruct the emotions of that moment, the doubts, the thoughts, the questions. If I try to go back in my mind, beyond the sun, the sky and the sea, I remember a progressive paralysis of the body and my thoughts. I remember my inability to go beyond that story, to question it. I could not find myself in that story, nor could I connect to my father, uncle and grandmother the existence of that painful absence that I had up to that moment ignored. That constraint lasted for years. It must have been the silence conspiracy that, like a love strategy, prevented me from talking about it with my mother and father. It stopped me from asking questions and trying to understand. The same pact of love impeded any exchange with my sister and brother who were both on the same island. Ada’s discovery was a secret that my own silence continued to stroll along with.

It was by a tragic and banal chance that Ada slept at nonna’s house. It was the responsibility of Fascists to conduct the racial census which identified the houses and families. It was the responsibility of the Nazis to develop the extermination plan. Both made the death of the three people who lived on that floor possible.

The Nazi’s lists [10] – they were the ones who carried out the roundup in Rome that October morning included only one Tagliacozzo family on the third floor. In fact it was one family that lived in two apartments. Adding to the confusion, only one of the two doors had the name plate. It was there that the Nazis knocked. It was at that door that they delivered the infamous note written in broken Italian: “1) Together with your family and with the other Jews pertaining to your household you will be transferred. 2) You must bring with you: a) food for at least eight days b) ration cards c) identity card d) glasses. 3) You can take: a) briefcase with personal effects and underwear, blankets, etc. b) money and jewels. 4) Lock the apartment, resp. (sic) the house (who knows what it meant, nothing good even if incomprehensible) and take the keys with you. 5) Sick people, even very serious cases, cannot for any reason be left behind. An infirmary is located in the camp. 6) Twenty minutes after receiving this notice, the family must be ready for departure.” I imagine that when grandmother Eleonora and uncle Amedeo were handed the note, they didn’t think of a death sentence. However, a knot tightens in my stomach when I think of the three people next door. I physically perceive the fear, the attempt to conform to those orders given in a foreign language. The effort to remain silent so as not to alarm and reveal the rest of the family that had remained invisible behind the other door. What happened in the other apartment is not clear. My father vaguely remembers, perhaps his earliest memory, a hasty escape. There was no name on their door. Family legend speculates that when grandmother Eleonora was asked who lived in the apartment next door, she vaguely replied that they were displaced people from out of town. The Germans believed her and we all owe our life to her lie. I don’t know what would have happened had the Nazi been more zealous. I’ve always tried not to think about it. Even during my worst nightmares I had to surrender to the fact that my father has remained alive. Sometimes, when my children were small and slept at their grandparents’, this thought marked the moment of parting from them, a subtle anxiety accompanied me throughout the hours of separation.

From that moment on, their fates blur with those of the other Roman Jews captured that day. First, they were taken to the Military Academy on the Lungotevere. I imagine that Ada remained with nonna Eleonora. For the second time, Roman Jews confided in their hope. It was the second and last time: they thought that none of this could happen in the city of the Pope, that he would protect them. In fact, the Vatican did something, protected some Jews who had converted to Catholicism. The others, the members of the first covenant, were left to their fate.

A few years ago, a commemoration of the round-up began to be held at the Military Academy. My father was one of the proponents of the initiative. The first time I was afraid that he would feel sick: none in the Jewish Community had ever returned to the courtyard. For decades, countless young men have received military training in that compound, most likely ignorant of what happened there. Now, however, the memory of those events has returned to this place. The Ha Kol choir has performed there in Hebrew. I imagine that in 1943, someone, frightened in the face of the unknown, recited the Shemà [11]. And now again, decades later, Hebrew resounded in that courtyard: not as the voice of a supplicant this time, but one proud of history, culture, and identity. And also of tragedy. Sometimes, the pride of the catastrophe is a way to make peace with the destruction.

The train left the Tiburtina station on Monday the 18th of October. A phonogram from the Rome police headquarters to the Ministry of the Interior reads: “Today at 2 pm the DDA train left the Tiburtina station with 28 wagons of Jews (about a thousand) including women, children and men headed to the Brenner Pass. No accidents”. In fact, no one objected. To no one, that procession of desperate souls appeared unfair. Nobody found the courage to rebel. Was it cowardice; or the result of twenty years of dictatorship and Fascist school teachings; or the general attitude of contempt toward the Jews, foreigners and people who did not conform? All of these factors weighed in. There was no rebellion and the only remnant of that day are little handwritten notes tossed from the train. After my grandmother’s death, among old papers amassed and forgotten, a heartbreaking note surfaced: “The three of us are well. Leaving Rome today. Warn porter on S. street to spread warning. Thanks Amedeo.” What did “The three of us are well” mean? That they had not been harmed? That they weren’t afraid? That they were together? Evidently someone found the note and delivered it or had it delivered: who was this person? What did she think when she read it? Why did she deliver it? Besides, what did the doorman do? How did he warn the other Tagliacozzo family that had run away and was in hiding? Evidently someone had contacts, passed by the house … Did grandmother, grandfather, dad and uncle have time to find out what had happened? What did they think? But, above all, did parents and grandparents manage to protect the children from the absurdity into which life had plunged them? Only the urgency of writing authorizes me to askspecific questions, which are senseless even if they were to receive precise answers.

A few years ago Noemi Procaccia, to whom I dedicated this book, and who was frequent company at our home, showed up with the usual chocolate and a few photocopies from an archive where she was working. I don’t think we discussed them at the time since my children were still little and her visits were always festive. Now she is gone, and I have kept those hand-delivered pages, that carry a sign of compassion: “Transit documentation of train of deported Jews from the Padua station on October 19th, 1943.” The heading is from the Italian Red Cross and included are pages of the inspector’s diary[12]. The letter from the president of the provincial committee concludes addressing the Union of Jewish Communities: “I am pleased to communicate to this community the feeling of solidarity that our Association has always felt for the oppressed and the victims of injustice”. The pages of the diary do not need comment: “At 12 noon today, unannounced, a train of Jewish internees, coming from Rome, stopped at our Central Station. They don’t want to open it. For almost an hour, we discuss with the German commanders of the train and the station, and finally we are granted permission to lend assistance. We are four sisters on duty and, secretly, we call two more. At 1 pm, they finally open the wagons that had been locked for 38 hours! Crammed in each car were about fifty people: children, women, old people, young and adult men.

We had never seen a more gruesome spectacle! The bourgeoisie torn from their homes with deception, without baggage, without assistance, were condemned to hunger, thirst and the most humiliating promiscuity.

We feel helpless and unprepared to care for all their needs. A person, a man, died at night in one of the wagons in the dark. As there is no light, his fellow travelers only realized what had happened because suddenly they no longer heard him stir and then they gradually perceived the cold of death. A van transported him to the mortuary cell. We are paralyzed by pity and quivering with rebellion, by a kind of terror that dominates everyone, victims, Italian railway personnel, people who begin to understand from the street. We.

The train stops for four hours and we manage to distribute jam, bread, fruit, milk powder for the children, and medicines. Everyone helps us, the tireless railway workers who fill flasks with water and who hold the relief baskets, women who run home and bring us swaddles for the little ones, blankets, clothes and, taking a personal risk, manage to give them to us, and above all the owners of the station canteen who give us everything they have: kilos of cheese, salami, hot soups. It is the Italian generosity that one more time shows itself in the most moving way, contemptuous of danger, knowing full well that what is given will never be returned, and it is only paid by the sense of gratitude in the eyes of people destined to death.

Reinvigorated a bit by the food and perhaps comforted by the profound humanity they sensed from us, this mass of unfortunate people is made to go back into the wagons and the wagons are locked again. We remain distressed and alone under the station platform roof. We feel that this human wickedness is far more terrible than war as it pursues, seizes, and tortures innocent and defenseless creatures.”[13].

The journey to Auschwitz lasted five days. Ada and grandmother Eleonora were killed upon arrival. A recently found document from the SS Hygiene Institute in Rajsko, Auschwitz, reports “the examination of the pus of Amedeo Tagliacozzo, registration number 158627.” This means that on the 4th and 5th September, 1944 he was in block 6 of the BIIf hospital sector in Birkenau with a thigh abscess. The document is signed by the head doctor of the camp, Josef Mengele.

Now I have to stop writing, stop thinking, stop looking for the faces of Ada, grandmother Eleonora and uncle Amedeo among those seen by the nurses of Padua.

In my father’s memories, the first days of “the family of the door without a name” were chaotic: they were probably given hospitality by a friend of grandfather Arnaldo. Father says that grandfather and grandmother returned to the apartment to get money and other personal items. I cannot imagine when nor if they were aware of the risks. Then, at least nonna and the children went to Piazza Vescovio where they were lodged by the Spanish nuns. A few days later, however, close to curfew time, the nuns threw them out fearing searches. It was nightfall, in a city at war, they were on the street: a thirty-six-year-old woman with two children, five and seven year old, and nowhere to go. I don’t know where my grandfather was, my father doesn’t remember or never knew. For him the memories of that period are confused and he always says he can’t “put the dates in place.” He is a bit obsessed with it, he would like to succeed in reconstructing a precise chronology. And in doing so he downplays the small fragments that make up the memories of a child. I cannot distinguish what is a function of his meticulousness, and what is a strategy to overcome the trauma of those months of loss.

My father never asserted and elaborated that loss. With no date of death, no place to cry, there was only an absence. Even that slowly faded away together with hope. One day, this orphaned family, full of holes and murdered relatives, regained some form of serenity. Two certificates from the Jewish Community dated April 28th, 1964 —the year of my birth and twenty-one after— state that each one of them was “captured by the Germans in Rome, for racial reasons. The place of deportation is not known and until today it was not possible to locate them. This certificate is issued on plain paper for all uses permitted by the law.” When school children ask my father how he felt at the announcement of Ada’s death, he tries to explain that there was never an announcement, the news never arrived. There is no moment that separates before and after. At one point Ada disappeared and she never came back.

I don’t know if in that small family of survivors there was some ritual, actual or unspoken, that allowed them to share her memory. Only once I heard my grandmother mention Ada: I was grown up and she was paralyzed in bed —her mind confused. Agitated, she said something about Ada’s birthday. I already knew, and could not help but calm her down. Even then I didn’t have the strength or courage to ask questions. Now that she is gone and so is my uncle, the only one to ask is my father. Paradoxically, it is my decision to write so as to legitimize these questions. They are questions asked at the breakfast table, or through telephone messages or quick phone calls that do not suit either of us. His latest message: “You have too many questions, we can try…” or his last phone call: ”But what do you need all this information for?” As if he didn’t know what I’m writing about, as if each time we need to start over, give questions legitimacy, and ask for answers; as if it weren’t true that this attempt to write our history makes him tacitly proud and relieved. However, it is impossible for him to understand that I can have an active role in this story, that this story concerns not only our shared past, even though we did not both live it, but also my personal one. And not just the past, but also the present.

After the flight from the convent of the Spanish nuns in Piazza Vescovio, history becomes tangled again. It is difficult to reconstruct the timing and what happened to the rest of the family. For sure grandmother, father and uncle were lodged by the nuns of the Precious Blood in Porta Metronia.

A funny and mischievous smile lightens up my father’s face when he remembers the days at the convent. His naughty expression folding on the corners of the lips still resemble his photo as a child and that of my son who must have inherited it from him. If my father allows himself small memories, even in the stories of escape and hiding there must have been respite from terror, everyday life must have imposed itself inexorably.

The nuns prepared the hosts for mass. The scraps left after cutting the light and transparent round pieces were given to the children hidden in the convent as sweets. My father, I suppose thanks to his smile, always got some extra. Dad’s cousin has a more dramatic memory, of which I don’t know time or place: on the windowsill of a convent his mother sternly orders him to learn the Hail Mary and forget everything he knew in Hebrew. According to cousin Lello’s memories, there were also my grandmother, my father and my uncle. My father however, has no memory of this episode, even though, like all of us Jews from a profoundly Catholic country, he knows that prayer by heart.

From that day on, time at the convent moved slowly for my father. I don’t think he has direct memories of what happened in February 1944, but rather memories of later stories. His smile otherwise would be out of place. I talk about that February and the fate of grandfather Arnaldo in other pages. Of the rest of the family, I know only small fragmented stories. It is not known where uncle Attilio, the other Tagliacozzo brother, hid, probably in a hospital. He had an ailment of some sort. My father, letting a smile slip says that not every family silence concerns the Shoah, the war and the occupation. I’ll never know whether he wants to protect his uncle’s privacy or something else, dark and unspeakable. I don’t know much about grandfather Arnaldo’s two sisters: aunt Adele, cousin Lello’s mother, who also hid in a convent with her children, and aunt Olga with her husband whose whereabouts I ignore. They all managed to arrive safely until June 4th.

Grandmother Lina’s family, on my father’s side, had yet another story, making the family as a whole a cross-section of the destinies of the Jews in Italy during the Shoah.

The Zarfati’s too had a sewing and notions shop. They too were “casa e bottega” —the family lived in via dell’Oca, while the shop was a few meters away, at the beginning of via Ripetta. Grandfather Pacifico died between the outbreak of the war and September 8th. Grandmother Lina was very close to her father, who, during her entire life remained the yardstick of her Judaism: “My father did this” was her unquestionable mantra. This affection was crystalized in an episode that must have happened during the occupation and falls into the strange category of signs and dreams that still bound me and my sister decades after grandmother’s death. One day, nonna Lina, leaving the children in the convent, ventured around the city in search of something that no one remembers. Suddenly her long dead father, grandfather Pacifico, appeared to her. He addressed her firmly, ordering to immediately change direction: “You must not pass through here.” My grandmother, as I suppose she has always done in her life, obeyed her father’s order. Only later did she discover that, in fact, a raid was underway and her false identity card may have not passed the document check.

After the death of grandfather Pacifico, his wife Giuditta — nonna’s mother — remained in the house in via dell’Oca, with her other daughter Titti and her husband Aldo Polacco. He was born in Venice and, who knows how, ended up in Rome. Zio Aldo was religious. He had a diploma from the rabbinical college and was a hazan, a cantor in one of the synagogues in Rome. In a dramatically staged photograph he appears completely wrapped in his talled[14]. Aunt Titti, on the other hand, was already visually impaired and during the war she became completely blind. I don’t know what the three of them at Via dell’Oca did between October 16th and February 1944. In addition to the personal data, a record from CDEC [15]. states that uncle Aldo was arrested in Rome and deported to Auschwitz. It seems that in February, the police or the carabinieri, which one is not known, summoned him and grandmother Giuditta. The officer on duty, with long and convoluted sentences told grandmother that she should return home to collect what was needed for the trip. He made clear to her that she should leave and not return. He could do nothing however for uncle Aldo, who was detained, taken to Fossoli and from there to Auschwitz. “He was captured almost on the same day as my father,” my father writes in a laconic message from a ship that takes him back to Rome from the same island of my now distant revelation. “But I don’t know if they met at Regina Coeli [16] or in Fossoli[17]. All of the “I don’t know” drive me crazy, they make it impossible to reconstruct a story that makes sense. Who was this man who decided to save grandmother Giuditta and to keep uncle Aldo? He must have had a name, a history, an identity! Why did he choose him? Why was an elderly and frail woman saved and a thirty-three-year-old man, the care-taker of a blind wife, “taken away”? What did that officer tell his wife and children, if he had any, when he went home that night? Did he know that he had granted salvation to one person and sentenced the other to death?

No one knows what happened after the arrest and where grandmother Giuditta and aunt Titti, now left alone, found refuge. My father remembers that, after the liberation, they found the house empty and grandmother Giuditta went from neighbor to neighbor trying to recover something. In fact, some of the furniture returned to the apartment in via dell’Oca. Her search apparently yielded some results.

Now that so many years have passed, now that I am traveling through the desert, now that I can try to look at the Sphinx in the eyes, only one thing I know with absolute certainty: these were all normal families. Whether slain dead or wounded survivors, they were not heroes but people: simple or complicated; honest or dishonest; handsome or ugly; young or old. They were ordinary people, with flaws and merits, that had nothing to do with the reason for which they died or survived. Luck, intelligence and means perhaps made a difference, but who knows to what extent each of these elements weighed. Today nothing more can be done about it. Making them heroes as the public discourse tries to do, means to remove them from history, to reduce the Shoah to a category of ethics instead of human responsibility. Doing this is an affront to their memory as human beings, men and women, adults and children, elders and infants. Artists and clerks, scientists and shop-keepers, criminals and beggars, doctors and doormen, thieves and bankers: they all winded up in the hole of history. But they were normal people, not heroes. Perhaps sometimes desperation made one of them a hero. This is why I prefer to do away with heroism. I rather believe in good citizenship, every day and at all times, of individuals and institutions. I believe in good laws and virtuous behavior. Living in a society that needs heroes terrifies me. As does the idea that the times that threaten to come will again require desperation and heroism.

I can picture in my mind loves and tensions, likes and dislikes of all these families. They were all people of character, both the Tagliacozzos and the Zarfatis, quarrelsome and passionate in their affections. Simple in their being, rigorously attached to life even when the fractures of history had broken them. In the years immediately after the war, family disputes raged over the division of the mutilated family’s inheritance. My father reconstructed a violent quarrel between grandmother Lina and uncle Attilio. “You drive me crazy,” he says, turning brutally to his sister-in-law, “now I’ll kill myself.” “You are lucky,” my cruel grandmother replies, “I can’t, I have two children.” Deep in my bones, I feel this concept of ferocious family responsibility.

For years, during a hike in the mountains or wherever physical exertion was required, I wondered if I would be able to endure it with my children in my arms. If the desperation of the escape would have given me the necessary strength. Now that the children have grown up, I know that I am the one who would not to make it. I wonder if I would be able to swallow the tears and the agony of letting them go alone, strong and young, towards safety. It is a comfort to know that my husband and I have tried to do our best in the face of the accidents that happen anyway in times of peace. But this is not enough to give me confidence: uncertainty remains a constant companion.

The first thing my father described to me of June 4th, 1944 was the silence: in the city, suspended between the hasty flight of the Germans and the arrival of the Allied troops, silence reigned. Other people I interviewed also had a clear memory of those hours of silence. It must have been extremely quiet if it left such an impression even on my = six-year-old father. The silence of that day must have been the opposite of the rumble that, in the biblical desert, resonated in anticipation of the divine word. The opposite of the petrified ice of silence that penetrated the ears of the deaf. That silence was also pregnant with life.

Only in the afternoon of that day, my grandmother left the convent holding dad and uncle Davide by hand. She took them to Porta San Giovanni “to see the Allies” entering the city. The voice of my father, who remained steadfast and clear in narrating the tragedy, suddenly breaks, narrating the liberation: “It was festive,” he says without adding anything else. I translate: it was the end of a nightmare. Still unaware of what had happened to those who had disappeared, in those hours they could happily celebrate the end of confinement, danger, and fear.

Slowly, almost in spite of everything, life began again. Already in July my grandmother applied to be readmitted to teaching. Returning to her job from which she had been removed because of the racial laws did not happen automatically: it took applications, stamps and a lot of paper. Moreover, the racist laws began to be repealed only in January 1944 due more to the robust allied intervention than the will of the Badoglio government. Many months had past since the armistice. Meanwhile, in September 1944, while the war was still raging, the North was in the hands of the Italian Social Republic, and the partisan resistance in full action, the search for the missing began. The Jewish Community of Rome, temporarily placed under Allied control, issued a first document certifying that the missing members of my family had been captured and that “no information is available concerning the place where they were deported.” Meanwhile, my father says, “we ate the Americans’ white bread, chocolate from military rations, we chewed American gum for the first time, but the war is still going. Many would die before its end. And in the North Jews were still being deported”.

On February 10, 1945, nonna Lina sent a telegram to the prisoners’ office in Moscow. I recognize her handwriting on the draft of the letter and the address of the house where I live in the place of the sender: “I request information on the Jewish civilians deported from Rome on October 16th, 1943: Tagliacozzo Sabatello Eleonora, born in 1869; Tagliacozzo Amedeo was Davide born in Rome in 1898; Tagliacozzo Ada di Arnaldo born in Rome in 1935 stop. Deported from Rome-Fossoli April 1944 Tagliacozzo Arnaldo was Davide born in Rome in 1901.”