By reimagining landmark New York buildings like the Astor Library, which became the Public Theater, Giorgio Cavaglieri championed the architectural preservation that shaped the modern city

“Architecture,” said Vincent Scully, a top historian of the field, “is a continuous dialogue between generations which creates an environment across time.”

It’s a perfect line with which to mark the 100th birthday of Giorgio Cavaglieri, an Italian-Jewish architect who reinvented American buildings to reflect that historical conversation. He made a name with buildings he built himself and as a leader among the 1960s-era preservationists who took to the streets to save the humane qualities, beauty, and economic potential of old structures. As befits an exile, Cavaglieri defied easy definition. He wasn’t overlooked: When he died, in 2006, at 94, theNew York Times ran a richly detailed obituary. But Cavaglieri left no icon of personal style to match fellow émigré Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum, no lasting transcendental aura like Louis Kahn’s. His sense of architecture as an act of valuing the past, however, created a legacy that includes recent projects like New York’s popular High Line, a rusting freight track transformed into an elevated park.

Working at a time when urban clearing went too far, Cavaglieri—Ada Louise Huxtable, former architecture critic of the New York Times, told me—taught America “a lesson we needed to hear.” Elected as president of the influential Municipal Arts Society in 1963—the nonprofit is dedicated to urban planning in New York—he ran the society for three years, which gave him a bully pulpit on zoning issues and other questions affecting how the city should grow. New York’s current, and sometimes stricter, zoning laws reflect Cavaglieri’s ethos.

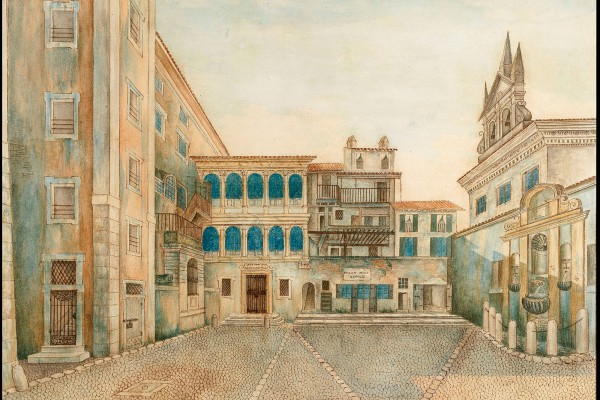

Cavaglieri was an elegantly lanky, mustachioed man with a bony but sensitive face, a narrow nose that looked like a slightly battered soup spoon, and long-fingered hands that drew his ideas in the air. He zipped around New York in one Alfa Romeo after another, returned to his native Venice often, painted its floating world in many canvases. In an unpublished memoir, he wrote that the sight of the Doge’s Palace from the Piazza San Marco when he was 4 years old “influenced my decision years later to design buildings.”

The new world, Cavaglieri learned soon after he escaped to New York from Mussolini’s Italy in 1939, was often not as reverent of its buildings as the old one. He joined the revolt against urban ruin when he protested against the wrecking of McKim, Mead & White’s splendid Penn Station in the heart of Manhattan. The station was torn down in 1963, but its demise made preservation into a public cause.

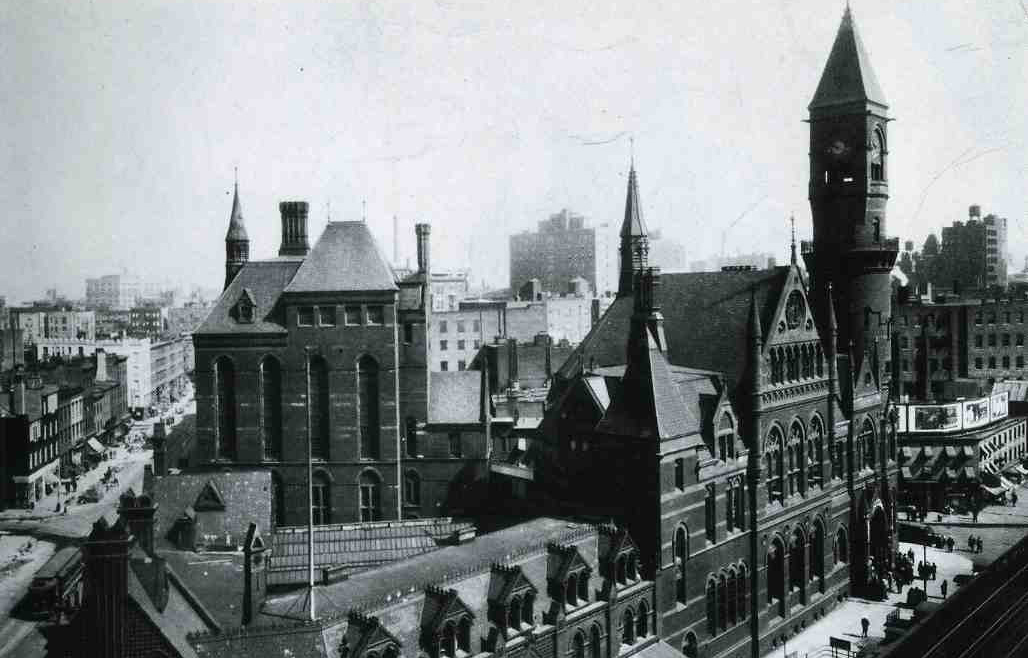

“I came to be involved, in the early 1960s or late 1950s, in the political groups that were then agitating for the preservation of the old Jefferson Market Courthouse,” Cavaglieri recalled in a 1982 interview with the preservation historian Charles Hosmer. It was his decisive moment. The courthouse, where Sixth Avenue passes 10th Street at the center of Greenwich Village, was designed by Calvert Vaux—who also contributed to the design of Central Park—in collaboration with Frederick Withers. Its Victorian Gothic style is romantically quirky. But it had fallen into decaying disuse. The clock on its high tower, by which villagers had told time for decades, stayed stuck at 3:20.

Cavaglieri helped collect signatures to restart the clock and save the Old Jeff. Turning the Jefferson Courthouse into a library in 1967 earned him critical raves. He became an international figure for elevating into an art form the so-called “alteration work” many architects looked down on, as architect-writer John Morris Dixon put it recently in the professional architectural journal Oculus.

The pioneering work on the Old Jeff brought Cavaglieri his next big project. As he was sitting in his office one day, Joseph Papp, the legendary theater producer and director, burst in. Papp, Cavaglieri later recalled, felt right at home in the bare-bones, unpretentious office. The willful architect and driven theater man sized each other up. Then Papp told Cavaglieri he was looking for spaces in which to house his nascent Public Theater, and he asked the architect to accompany him to look at one such space, the high-ceilinged former Astor Library at 425 Lafayette Street. The building’s elegant Italianate personality attracted Cavaglieri, and he took the job.

“Joe didn’t fire Giorgio, and when you’re talking about Joe that’s saying a lot,” recalled Bernard Gersten, who was Papp’s right-hand man in those years and now runs the Lincoln Center Theater. “He admired Giorgio as a Venetian, as an Italian, as an artist.”

To understand Cavaglieri’s work, one needs to go inside his projects, where the alchemy of matching the old with the new took place—for example, the Jefferson Market Library, subject of a new $7.9 million renovation that began in 2007. Though the scaffolding outside won’t come down for a while, refurbished Cavaglieri interiors reopened last month. They include a soaring second-floor reading room, for which Cavaglieri had to clear out Withers’ three upstairs court-rooms. He drew controversy at the time from purists by replacing some stained glass windows in the room with transparent glass; he argued that the contrast actually enhanced the impact of the stained glass. The modernized integrity of his choice is, I believe, obvious to anyone visiting the library.

The term architects use for projects like the library or the Public Theater—currently undergoing its own re-renovation—is “adaptive reuse.” It defines the transformation of existing structures for new purposes, bearing a double theoretical edge that rebuts both fetishists of original detail and the wanton destroyers of old buildings. “When a local historical society squeezes from the public a few dollars and pretends to restore something, cheating, to some extent, the future public in making them believe they’ve got the original farmhouse or the original building to look at, that’s something that is not realistic and not true,” Cavaglieri said in an 1982 interview.

Cavaglieri’s personal story helps to explain his balancing act of old and new. Growing up in a wealthy Venetian-Jewish family, no sooner had he become an architect than he faced a basic aesthetic-political juncture. He could choose either the neoclassical, sometimes swaggering styles nurtured by Italy’s Fascist regime or the more functional, austerely geometric directions influenced by the Bauhaus, the evolving International Style favored by some of the era’s most prominent architects. “It was assumed,” Cavaglieri wrote in his memoir, “that people of our ages [sic] would take sides.” The more his professors taught Fascist-tinged neoclassicism, the more he studied architecture “pushing for simplified geometric forms,” he wrote. Meanwhile, other pressures affected him. Getting work as an avant-garde architect was harder than complying with a cultural imperative “to protect the historical patrimony,” as he put it.

In other words, he had to learn how to reconfigure structures that were decades or centuries old. His thesis at Milan University re-imagined an old apartment building in the center of town as a commercial structure that would also include a theater. In the United States, he made a career with such projects, but what really distinguished him was a personal modernism that was especially thoughtful and resisted cold order for its own sake.

Family connections helped the young architect in prewar Italy in the 1930s. His father was an executive with Assicurazioni Generali, a powerful international insurance firm based in Trieste, Italy, who ran the company’s real-estate division for a while. The company became Cavaglieri’s first client, and he opened up a small practice. But military duty soon had him designing airfields for the Italian army in Libya. When he died, an Italian obituary-writer wrongly called him “Mussolini’s architect.”

He was, of course, nothing of the sort. When Mussolini’s anti-Semitic laws erased Jews’ status in Italian society, Cavaglieri fled to New York in March 1939. He arrived here with no more than $150, the family’s sizable assets having been seized by the Fascists. With the war under way, Cavaglieri joined the U.S. Army as an infantryman, and he ended up designing field hospitals and bridges for the U.S. Army as it fought across Europe.

After the war, having settled in New York with his wife, he struggled for a few years before earning sudden recognition. He was practicing out of an office in the well-known Fisk Building, at 250 West 57th Street, when the building’s owner asked him if he’d redesign the sculpted dark wood of its facade and lobby. Cavaglieri revolutionized the building with a front of modern metal and glass. In a 1949 review in The New Yorker, the critic Lewis Mumford wrote that Cavaglieri “deserves public thanks for carrying through this job with tremendous reserve.”

His career having taken off, Cavaglieri spent the 1960s dashing all over New York City as both an activist and an architect. He designed a few buildings from the ground up, including libraries in Kips Bay and Riverdale and two union halls, one for workers in the theater industry and the other for hotel employees. These projects, said Andrew Tesoro, a New York architect and Cavaglieri’s nephew, weren’t grand, but they were dear to his uncle. “He got to use the palette of the modern architect, even if they were on a small scale,” Tesoro said. “He loved them for their left-wing implications. He loved them because they each had a face to the city.”

It was through one such project that I came to know of Cavaglieri. In the early 1950s, he built a home in Pleasantville, N.Y., for Frederick and Lili Arno, my mother’s parents, themselves refugees from Trieste. An orderly, single-level rectangle from the front, it unfolded inside into an embrace of light and space, skylights above, almost every view a threshold to someplace open and intriguing. Its clean geometry absorbed the formality of my grandparents’ European furniture but transcended it with white walls that merged with wall-sized windows to trees and sky. The design showed how second-nature the International Style was for the architect but also reflected the reserve Mumford had noticed, a knack for intimate practicality that collaborated vigorously with the life of a family or union members or kids checking out books in Greenwich Village.

The International Style the architect applied to the Pleasantville house bore an edge of the postwar era’s sunlit optimism. But my childhood inhabitation of its functional beauty also touched me with a sense of great losses that were overcome but never forgotten. Memories of those who never escaped Fascist Europe weighed on those who did: “We few, we lucky few,” my mother would say.

My grandfather died in 1967, the year Cavaglieri finished his bold Jefferson Market redesign. As I grew into my teens, I spent a lot of time with my grandmother in her home. I often asked her about the past. “Who built the house, Granny?” I asked her one day. “Ach,” she said, “Cavaglieri.” She tossed out that last name as if it held a bigger truth that didn’t have to be explained. “Is he famous?” I inquired. “No,” she said. “But he did a good job on our house.”