Storie Della Storia del Mondo, Laura Orvieto’s Timeless Introduction to Homeric Lore.

Maxine De Winter in conversation with Alessandro Cassin.

Maxine De Winter is a TV journalist. She lives in London and Livorno. Alessandro Cassin is publishing director at Centro Primo Levi.

Laura Cantoni Orvieto (1876- 1955) was an important Italian Jewish writer, journalist and intellectual active in Florence in the first half of the 20th century. Beloved by several generations of Italian children who grew up with her tales of Greco Roman antiquity, today, her work is being rediscovered and reevaluated by scholars. Born in Milan, Laura Orvieto moved to Florence after her marriage to Angiolo Orvieto, a poet, and founder of the magazine “Il Marzocco.” The couple was friendly with, among others, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Eleonora Duse, Amelia Rosselli, Giovanni Pascoli, and Luigi Pirandello. In 1909, Laura Orvieto began publishing children’s books with the pedagogic ambition to transform society starting from the children. She soon became, particularly (but by no means exclusively) among Jewish families, somewhat of a hero at the level of Maria Montessori, who was roughly her contemporary.

Maxine De Winter: When I asked you about the books that had the most significant impact on you as a child, you began your shortlist with Laura Orvieto’s Storie Della Storia del Mondo. Can you explain?

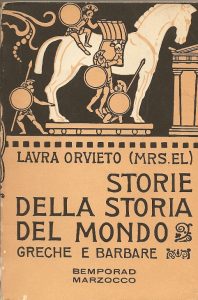

Alessandro Cassin: It was love at first sight. I loved the title, which translates roughly as Stories of the Story of World, promising the widest of scopes; the dimensions (small and perfect for a child’s hands); and the cover which resembled the images on Ancient Greek vases. I loved it as an object before I could read, I would wait impatiently for my father to read out loud from it. And I loved how the stories dovetailed one into the other. Each stood on its own, but together they formed a whole.

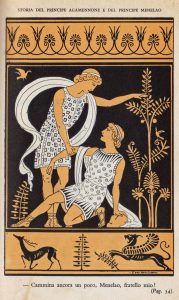

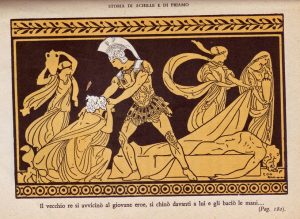

I must also mention the illustrations: each chapter began with an historiated initial, and every two or three pages there was an image relating to the tales, drawn to look like an image from Greek pottery or painting. Together they were a sort of introduction to ancient Greek art.

The timing of the tales, was perfect as were the endings, always promising more to come:

— And then? – Asked Leo.

— Then Priam became king of Troy.

— And then? Asked Lia.

— Then there’s another story, but I will tell it to you another day.

MDW: I am told that many children were given her book to read in school, was that the case with you as well?

MDW: I am told that many children were given her book to read in school, was that the case with you as well?

AC: No, but like many Italian elementary school children, I remember the day, in fourth grade, when the teacher announced we were going to begin reading sections of The Iliad (as for many other subjects, that first encounter was followed by more in-depth readings in middle school and later in high school). I was surprised to realize how familiar I was with many of the characters, the storyline, and the pathos. The familiarity stemmed from having read over and over Laura Orvieto’s classic.

Orvieto introduced me as tens of thousands of Italian children to the city of Troy, a multitude of quarreling gods and goddesses, as well as heroes such as Agamemnon, Menelaus, and of course, Odysseus and Achilles.

MDW: Growing up, aside from the book we are discussing, were you aware of Laura Orvieto as a writer and intellectual?

AC: I think most Italian Jews took great pride in her achievements. Particularly in Florence, where she lived, she was a sort of celebrity.

In our house Laura Orvieto’s name was always pronounced with great reverence; both my grandmother and great-grandmother had known her well.

I knew she had written many other books, but none of the other captured my imagination in the same way. I had a copy of her first book Leo and Lia, the story of two Italian children and their British governess.

MDW: You consider Storie Della Storia Del Mondo a “classic”?

MDW: You consider Storie Della Storia Del Mondo a “classic”?

AC: For me, it is undoubtedly a “classic” among Italian literature for children, next to Le avventure di Pinocchio, Il Giornalino di Gianburrasca, and the works of Emilio Salgari, all of which were published by Bemporad -Marzocco, a Florentine Jewish publisher.

MDW: Some would argue that a Classic should not derive from other works…

AC: Orvieto’s book is in no way derivative, nor an abridgment. It uses Home and Greek mythology as source material to create an autonomous work made of compelling plot-driven tales. Written in 1910, it reflects the pedagogic ambitions of that time, and more specifically, the reformist outlook of the generation of Italian Jews that had emerged from “emancipation”. These were highly motivated pedagogues, writers, and publishers who believed that the future was to be built starting from the children’s education.

When I was working as a journalist, I often heard the mantra that newspapers are made from newspapers. Storie della Storia del Mondo is a rare case of a “classic” made from the classics.

MDW: In what ways does Orvieto depart from a simple re-telling of The Iliad.

AC: Her stories explain the genesis of the Trojan war drawing from myths, legends and later tragedies. The narrative conceit is that of a Jewish mother (circa 1910) telling stories about the Greeks and the Barbarians to her children Leo and Lia, who interrupt the narrative with their questions and prodding. Within this scheme, she introduces themes and life lessons that are important to her.

Two examples ( my translations) will illustrate the subtlety of her technique. When narrating how it came about that of all the powerful kings of Greece that aspired to marry Helen, she selected the relatively modest Menelaus, Orvieto introduces the concept of being “worthy”. The positive value of striving for something rather than acquiring it through brute force, hereditary, or the will of the gods. She is introducing an idea of human being that at the time was not the prevalent one.

Menelaus hardly ever spoke to Princess Helen and did not tell her that he loved her. He knew that all the young people of Hellas wanted to marry the beautiful young girl; that the strongest heroes or the richest kings, the most handsome princes, would be happy to have her. He said nothing but tried to become better and stronger, to be worthy of her.

— What does worthy mean? – asked Lia

— What does worthy mean, Leo? Mom asked.

— I know it for myself, but I can’t explain it, Leo replied.

— And who explained it to you? – said Lia.

— Nobody. I understood it by myself, little by little. It is something that cannot be explained.

Mom and Leo were at a loss, but Mom finally found the explanation.

— Well, being worthy of something means finding a way to deserve it; isn’t that so Leo?

— Yes, that’s right, to deserve it. Menelaus was precisely trying to deserve Helen.

Later on, describing how “some Italians” descend from Aeneas and the Trojans, she writes:

“Aeneas,” said a divine voice, “which of the gods commanded you to fight with Achilles?” You are stronger than all the others, and you can win them, but you cannot defeat Achilles, and you don’t have to fight with him.

— Who was talking? Asked Leo.

— It was Poseidon, the god of the sea. The gods loved Aeneas and had made him the leader of the Trojans who would be saved after the war. So it was indeed Aeneas who led the Trojans to Italy and became their king. And if the story they tell is true, some of modern-day Italians are the children of the children of the children of the children of those Trojans.

— Then I’m a Trojan, Mom! Leo said.

—No, you are Jewish. The Jews have a completely different story, which is also very beautiful. I said that “some” Italians descend from the Trojans: others came from Greece, some from Germany, others were already here when the Trojans came. But let’s go back to Achilles …

The two heroes from The Iliad with whom children are most likely to identify are Ulysses and Achilles. Orvieto makes sure to tell the stories of how one tried to dodge the Trojan war draft by pretending he was crazy, the other by pretending he was a woman.

First published in Florence in 1911, Storie Delle Storia Del Mondo was an instant success selling a staggering seventy thousand copies by 1938.

First published in Florence in 1911, Storie Delle Storia Del Mondo was an instant success selling a staggering seventy thousand copies by 1938.

Orvieto’s proud display of her Jewish identity in this and in her other children’s book did not go unnoticed by fascist censorship after the Gentile educational reform. In 1929, before issuing a reprint of her first book, Leo e Lia. Storia di due bimbi italiani con una governante inglese, her Jewish publisher, Enrico Bemporad, asked her to eliminate some chapters that may offend the new political sensibility. In particular, a chapter where Leo, the little boy, asks: “Is the King Jewish?”

When, in 1938, the Ministry of Popular Culture issue a list of Jewish and Jewish sympathizing authors that were no longer to be published, Laura Orvieto was among them. In 1939, with Storia di Angiolo e Laura she turned to autobiography, again using hers and her husband’s plight as persecuted Jews, to further her belief in educating through storytelling.

During the years of persecution, she and her husband survived by hiding in a nursing home run by Capuchin Friars in Borgo San Lorenzo, near Florence.

In Italy, in recent years, a growing number of scholars, spearheaded by the work of Caterina Del Vivo, have analyzed the life and work of Laura Orvieto.

More about Laura Orvieto in Quest, Issues in Contemporary Jewish History