Letters from Italian Jewish soldiers in World War I – who would die in the Holocaust

The Anticolis, for instance, had 13 children, of whom four would fight in WWI: yet they lost their citizenship and lives during WWII.

Letters written by Italian Jewish soldiers who fought in World War I, only to find themselves subjected to the Italian Racial Laws of 1938, have been compiled and put on exhibit by the Jewish Museum of Rome.

Ahead of WWI, Italy had 35,000* Jews out of a population of 38 million. Of these Jews, 5,000 joined the army, half as officers: 420 of them were to die during the war. Yet the surviving Jewish veterans were to find themselves ostracized under the Italian Racial Laws of 1938 enacted by Benito Mussolini, with the approval of the Italian king, Victor Emanuel III.**

The laws banned Jews from public office and higher education, as well as books written by Jews, among other things. And ultimately, most of the Italian Jews who fought for their homeland in WWI were to be deported and die in concentration camps.

Now the letters and personal items on display at the Jewish Museum of Rome tell us the personal stories of some of these men.

Four sons at war

The Anticoli family of Rome was typical of Jewish Italian families in the early 20th century.

Prospero and Flaminia had 13 children, of whom four fought in WWI. Renato and Giorgio were captured and killed by the Austrian army. Adolfo was also captured, but survived – only to die decades later in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

Gabriele was the only one of the four to survive both the war and the Holocaust. He saved letters, pictures and postcards from his father, friends, and relatives sent to him during his service in WWI.

Despite the financial difficulties Prospero endured, he claimed, because he had four children in the army, he supported Gabriele and took pride in him. “I’ll be happy when I know you have defended your homeland successfully, long live our King and our country!” the father wrote, though admitted in other letters that he often didn’t have enough money “to buy paper and envelopes to write letters” to his son.

“I would like to send you a gift as your aunt did but I can’t afford it,” Prospero wrote; and “I always pray to God, night and day, for your safety.” Prospero also suggested Gabriele seek permission to celebrate the upcoming Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur at the closest Italian Jewish community center.

Gabriele’s friends and family also encouraged the soldier with letters and gifts. His aunt sent him chocolate, razors and wool socks. A young cousin wrote: “I wish I was old enough to fight with you for our beloved homeland and defeat the Austrians.”

Among the letters were some from Gabriele’s brother, Adolfo, who was in the army at the same time. Adolfo wrote to Gabriele, “I hope we see each other soon and tell each other stories about the war.” As said, Adolfo did survive the war, but was killed in a concentration camp.

During the war, Gabriele served in the Italian army rifle regiment and was temporarily deafened by a grenade. Afterwards, he worked for the city of Rome until the enactment of the Racial Laws in 1938, after which he was fired. He moved to South America, returning to Rome in 1949 and died in 1967.

Multiple betrayals

As the exhibit in Rome’s Jewish Museum shows, the Anticoli family and the Italian Jews in general died without a homeland, despite their patriotism and devoted service, including in the military.

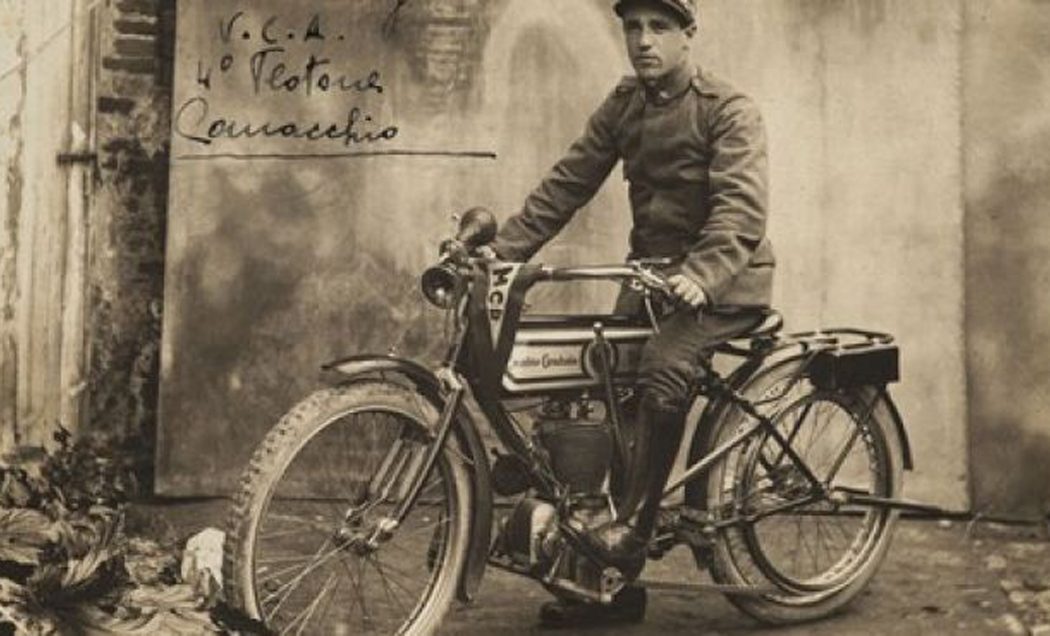

Other exhibits include a postcard written by another Jewish Italian soldier in WWI, Ermanno Jacchia, showing himself riding a motorcycle. (The content of the postcard was too degraded by time to be clear.) He sent it to his friend, another Jewish soldier, Gastone Bonfiglioli. Jacchia would survive WWI but die in Auschwitz; Bonfiglioli’s fate is unknown.

The exhibit also commemorates Italian Jews who achieved high rank in the pre-World War II Italian army. One such was the army doctor Captain Beniamino Citoni, who saved many Italian soldiers’ lives. Citoni had eight brothers and sisters, three of whom fought in WWI. He survived the war and the deportation as well, dying in 1959, home in Rome.

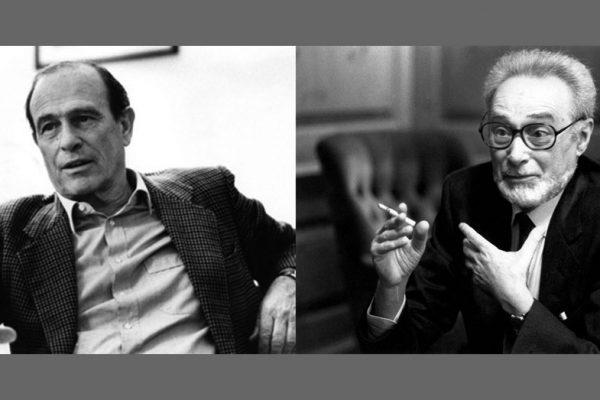

Another was General Emanuele Pugliese, who was awarded with several medals of honor for his military capacities. Pugliese had devoted his life to the army, leading the Italian forces in the war against Libya during WWI. He was also the general in charge of defending Rome from the “March on Rome,” in 1922, which was led by the Fascist leader Benito Mussolini. After the march, Mussolini and the Fascist Party came to power in Italy.

- The census indicates between 42,000 and 44,000 Jews before 1938