SILVIO ZAMORANI EDITORE

Silvio Zamorani Editore was founded in 1982.

It began by publishing art reproductions and photography: Saroldi, Biamino, Iavicoli Portfolio 1986, Tobiasson, Barletta, Giuseppe Pino’s Jazz amore mio. And serigraphs by Lucio Fontana, Capogrossi, Mondrian, Van Doesburg, Picasso, Gris, Matisse, Malevic, El Lissitsky, Rozanova, Casnik, Studio Walter Benjamin, Marino Marini, Mattioli and others.

The first book was published in 1985: an “exercise book” on the Hebrew alphabet, resulting from a workshop held by students of the Jewish elementary school in Turin. The poetic drawings illustrating the Hebrew letters are accompanied by annotations in four languages: Italian, Hebrew, English and Spanish.

Below are the categories in which the catalog is divided, with a selection of particularly significant titles, in chronological order

Semitic Philology. Texts and Studies on the Near East

1987 First issue of the journal “Henoch. Studi storico filologici sull’ebraismo” (1987, – 2004) of the series of monographic studies “Quaderni di Henoch”, in which twelve volumes were published between 1989 and 2002.

Selected titles from “Quaderni di Henoch” :

1992 Anghelescu Nadia, Linguaggio e cultura nella civiltà araba

1993 Pennacchietti Fabrizio A., Il ladrone e il cherubino. Dramma liturgico cristiano orientale in siriaco e neoaramaico

1995 Konstantin Tsereteli, Grammatica generale dell’aramaico

1996 Avicenna, Il poema della medicina

1998 Pennacchietti Fabrizio A., Susanna nel deserto. Riflessi di un racconto biblico nella cultura arabo-islamica

2001 Emanuela Braida – Chiara Pelissetti, Storia di Rawh al-Qurasi. Un discendente di Maometto che scelse di divenire cristiano

2007-2008 Elia di Nisibi, Il libro per scacciare la preoccupazione. («Kitab daf‘ al-hamm»)

2009 Davide Righi (editor), La letteratura arabo-cristiana e le scienze nel periodo abbaside (750-1250 D.C.).

Philosophy

1996 to 1999 “Quaderni di ermeneutica filosofica” series directed by Gianni Vattimo,

Selected titles:

1995 Mauro Zonta, Un interprete ebreo della filosofia di Galeno

1999 Graziano Lingua (editor), Icona e avanguardie. Percorsi dell’immagine in Russia

2001 Sergio Carletto, Ermeneutica della giustificazione. Lutero e le origini della Riforma

2008 Alessandra Jacomuzzi Cubo o sfera? Nuove prospettive per il Quesito di Molyneux

History

Selected titles:

1991 Fabio Levi, L’ebreo in oggetto

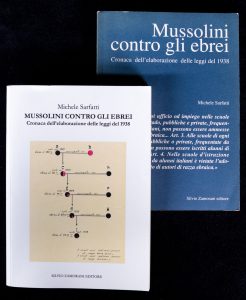

1994 (second edition, 2017) Sarfatti Michele, Mussolini contro gli ebrei. Cronaca dell’elaborazione delle leggi del 1938

1996 Grassi Fabio, L’Italia e la questione turca (1919-1923). Opinione pubblica e politica estera

1997 Rossi Artom Elena, Gli Artom. Storia di una famiglia della comunità ebraica di Asti attraverso le sue generazioni (XVI-XX secolo)

1998 Fabre Giorgio, L’elenco. Censura fascista, editoria e autori ebrei

1999 Levi Fabio, Maida Bruno, Brunetti Luzzati Sonia, I ventenni e lo sterminio degli ebrei. Le risposte a un questionario proposto presso la Facoltà di lettere di Torino

2001 Maida Bruno, Dal ghetto alla città. Gli ebrei torinesi nel secondo Ottocento

2002 Capristo Annalisa, L’espulsione degli ebrei dalle accademie italiane

2003 Levi Fabio, Dodici lezioni sugli ebrei in Europa. Dall’emancipazione alle soglie dello sterminio

2003 Ferluga Gabriele, Il processo Braibanti

2003 Fortis Umberto La bella ebrea. Sara Copio Sullam, poetessa nel ghetto di Venezia del ‘600

2004 Fortis, Umberto (editor) Dall’antigiudaismo all’antisemitismo. Vol. 1: L’antigiudaismo antico e moderno

Dall’antigiudaismo all’antisemitismo. Vol. 2: L’antisemitismo moderno e contemporaneo.

2005 Tallone Carla, Vigevani Jarach Vera, Il silenzio infranto. Il dramma dei desaparecidos italiani in Argentina

2005 Tonini Carla, Il tempo dell’odio e il tempo della cura. Storia di Zofia Kossak, la polacca antisemita che salvò migliaia di ebrei

2007 Cardosi Giuliana, Cardosi Marisa, Cardosi Gabriella, Sul confine. La questione dei «matrimoni misti» durante la persecuzione antiebraica in Italia e in Europa

2009 Segre Anna, Il coraggio silenzioso. Leonardo De Benedetti, medico, sopravvissuto ad Auschwitz

2009 Frattarelli Fischer Lucia, Vivere fuori dal ghetto. Ebrei a Pisa e Livorno (secoli XVI-XVIII)

2009 Ruspio Federica, La Nazione portoghese. Ebrei ponentini e nuovi cristiani a Venezia

2010 Taricco Bruno, Gli ebrei di Cherasco

2010 Calvo Silvana, A un passo dalla salvezza. La politica svizzera di respingimento degli ebrei durante le persecuzioni 1933-1945

2010 Allegra Luciano, Gli aguzzini di Mimo. Storie di ordinario collaborazionismo (1943-45)

2010 Rossi Doria Anna,Sul ricordo della Shoah

2011 Arbib Gloria, Secchi Giorgio, Italiani insieme agli altri. Ebrei nella Resistenza in Piemonte 1943-1945

2013 Filippi Antonella, Ferracin Lino, Deportati italiani nel lager di Majdanek

2013 Davide Tabor, Il cerchio della politica. Notabili, attivisti e deputati a Torino tra ’800 e ’900

2013 Alessia Pedio, Costruire l’immaginario fascista.

2014 First issue of the journal “Contesti. Rivista di microstoria”

2015 Renata Ciaccio, L’inferno è dirupato. I valdesi di Calabria tra resistenza e repressione

2016 Irma Naso, Magistri, scholares, doctores. Il mondo universitario a Torino nel Quattrocento

SIlvio Zamorani Editore also publishes:

“Pubblicazioni del dipartimento di Storia dell’Università di Torino” a series by researchers of Università di Torino.

“Laboratorio di Studi storici sul Piemonte e gli Stati sabaudi”, a series on medieval and modern history.

Religion

1999 Clementina Mazzucco, Lettura del Vangelo di Marco

2002 Alberto M. Somekh (editor), Kal le-Rosh. Il Seder di Rosh haSha-nah

2004 Ibn al-Munaggim and Qusta Ibn Luqa, Una corrispondenza islamo-cristiana sull’origine divina dell’Islam

2007 Michele Colafato (editor) Io che sono polvere. Sociologia della preghiera

2012 Milena Beux Jäger Padre Nostro. Una preghiera ebraica

2012 Alberto M. Somekh Miele dei favi

Narrations:

2000 Franklin Alice, Open shade. 20 Photograps

2000 Leone da Modena, Vita di Jehudà. Autobiografia di Leon Modena, rabbino veneziano del XVII secolo

2003 Schneditz Alf, Tobiasson Börje, Nella camera oscura

2004 Della Valle Pietro, Abbas re di Persia. Un patrizio romano alla corte dello scià nel primo ‘600

2005 Dino Otter, Émile Verhaeren. Un miroir à mille facettes du multiple univers

2017 Viola Lapiccirella, Einaudiani in corpo minore

Tactile books

“Tacto” series published with Tactile Vision

Selected titles:

1994 Levi Fabio, Rolli Rocco Disegnare per le mani. Manuale di disegno in rilievo, in Italian, French, and English.

1995 Levi Fabio, Rolli Rocco, Toccare l’arte. Torino.

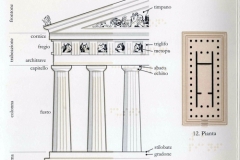

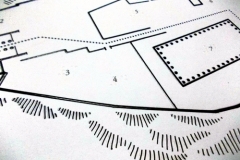

1998 Bird, Jenkins, Levi, Second Sight of the Parthenon Frieze. Published jointly with the British Museum Press

2001 Fabio Levi – Paola Slaviero, Le figure della geometria piana

2001 Gurioli Cinzia, Terra, Luna, Sole

2001 Rocco Rolli, Oggetti e disegni

2002 Aguiari Marinella, Rolli Rocco, Discover your Body

2004 Berlanda Alvar, Tabelle e grafici

2005 Gurioli Cinzia, La geografia dell’Italia

2006 Rocco Rolli (editor) Murazzi di tutti. Percorso plurisensoriale

2008 Maccarrone Giulia, Rolli Rocco, Elementi di architettura in Italia. Vol. 1: Greca, etrusca, romana.

2012 Bianchessi Elisabetta, Nature’s dots. In braille with tactile drawings about the landscape of Riserva Naturale delle Torbiere del Sebino, near Lago d’Iseo

In the field of tactile publishing, Silvio Zamorani Editore has also produced many books on behalf of institutions, museums and organizations.

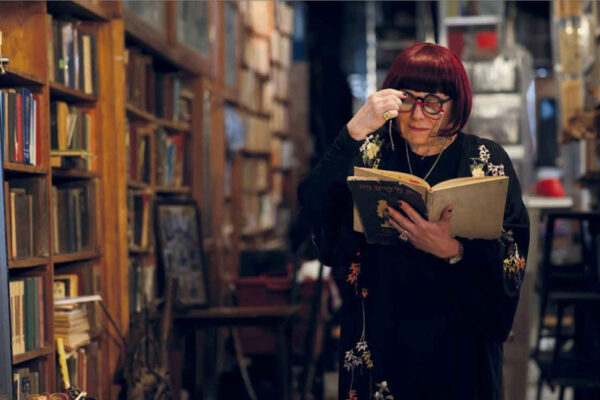

Since the 19th century, Turin has been one of the most active centers of publishing in Italy. Next to the eminent Einaudi, there are a number of highly specialized smaller publishers. Among them, Silvio Zamorani Editore. If publishing is always a group effort, Zamorani has grown around the personality, talents, and vision of its founder. A charismatic conversationalist, he outlined for us the connective tissue between his many activities.

Alessandro Cassin. Entering the courtyard at Corso San Maurizio 25, leading to the offices of the publishing house I noticed the picture frame workshop. I am fascinated by people who conduct parallel activities, you are a publisher and frame maker, how do you do it?

Silvio Zamorani. My activity as framer began in a very easy, almost spontaneous way. It has grown over the years and expanded to commissions in many countries around the world. Recently we completed a series of frames for Marisa Merz’s show at the Met Breuer in New York. Usually, when an artist appreciates how we frame his or her work, he then continues to use our services for years.

AC That is a true compliment to your work, but back to how you started…

SZ Oh, it’s a simple, bordering banal, story: around age 34, by virtue of my restless character (and this has been indeed my good fortune) I resigned from a promising editorial job at Einaudi. I had spent some great years there, but fundamentally, the more I observed the workings of that publishing house and their inside culture, the more I realize I had strong inner resistance to becoming one of them, or in any way, like them. So one day, without a further plan, I simply resigned.

AC What was your fear?

SZ In those years, Einaudi was very prestigious, ambitious and, in its own way, an elitist institution in Turin. Despite my critical eye, I realized that day by day I was becoming part of the small, brilliant, yet closed and extremely self-referential world, that Einaudi embodied.

One Friday afternoon, returning home from work I consulted with those whose lives would be affected by my resignation: my wife and my son. After pronouncing as if to convince my self the phrase “In fondo un piatto di minestra si rimedia sempre” (after all, there is always a way to earn a dish of soup), I sat at my typewriter and wrote my letter of resignation. My timing was fortunate: I left spontaneously just two years prior to Einaudi’s large crisis. Leaving on my own terms was certainly more desirable and reflected the way I wanted to face life.

AC Soon you began publishing on your own…

SZ That too, for the simple reason that publishing was the only thing I knew how to do. I had been around publishing and books, I felt a connection to the making of books, and thus it was the easiest direction to turn. Had I chosen some other direction I would have had to start from scratch.

AC How had you entered Einaudi?

SZ In the most banal way: I had been working for them as a freelance proofreader. One day to my great regret, they tell me: “because of union rules, we can no longer use so many external collaborators, thus we need you to become part of our staff.” It sounds strange today, but I knew from the start that I was not cut for that. Regardless I kept the job for seven years. I was working in production: proofreading, and all kinds of technical aspects. When I talk about my passion for making books I am not referring to an intellectual vocation, but to how a book is made technically, mechanically, that is all the work that must be done from the initial idea to the finished product. I was fascinated by the concrete making of a book.

AC After resigning from Einaudi you set out on your own…

SZ Yes and I faced several problems: I was not rich, I had been living hand to mouth from my salary and never thought about saving. And making books without money is not the easiest thing on earth… Further, I was very individualistic and was not sure I could manage a group effort, therefore I knew it was going to be a solo adventure.

I began trying to assess my skills: it seemed to me that like someone who can solve crossword puzzles, I only had a superficial knowledge of many different things.

When I look back at my reasoning, at my “business plan”, I have to smile. In my naiveté, I asked myself what I could do better than others that is relevant for publishing? I come from Egypt, so I know how to write in Arabic, I come from a Jewish family so I can write in Hebrew, not well, just enough to get by. I did not have the skills of a specialist…

AC What other languages do you speak?

I get by in quite a few, for no other reasons than the circumstances of my early life. My mother was Greek, so, as a kind of devotion to her and her family, I learned Greek. By my first grade, while children usually concentrate on their so-called mother tongue, I had to learn several alphabets: Arabic, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. I spoke French, Italian and Arab at school, Hebrew and Greek at home. In addition despite the fact that Egypt was in many respects a backward country, in schools, they taught us to read music. Besides all those languages, I had to master solfège. As a result, I became acquainted with multiple language systems, which I later realized, was a gift.

AC In Italy your were a polyglot in a country where few spoke a second language…

SZ Exactly: in those years, in Italy, most people did not know anything about Hebrew, not even that it is written from right to left. Many times Hebrew words or phrases were printed backward: Hebrew letters seem to rest on the top, so often typographers would invert it, thinking it made more sense graphically. Typesetting was much more of a challenge back then. We are talking about 1982; typographically speaking, we were at the close of an epoch and the dawn of the next. It was the end of traditional typography and the beginning of phototypesetting. The software was primitive and the challenges were many. It was not easy to compose words that run from right to left, within a text that runs from left to right—that is to say, Hebrew words within an Italian text— My modest advantage was my familiarity with multiple alphabets.

AC You were brave to set out on your own.

SZ Not brave, I just followed my instinct. My reasoning was very basic and down to earth. Aware that my linguistic skills did not constitute in themselves enough of an advantage, I start analyzing the Italian publishing world particularly its limits and small size. Italian is spoken only in Italy, think of the advantages of publishing in widely read languages such as Spanish or English… My (again very basic) solution to this limit was to turn to the art world of which I knew little, but for which I had great passion. It occurred to me that printing something connected to art, would bypass the confinement to a single language, and widen my potential market. If I printed a poster or an art reproduction I could sell it worldwide. Images do not need translation. Thus, considering my limits, I decided to concentrate on two activities: publishing books and printing art, which soon brought me to framing it as well.

AC Silvio Zamorani Editore from its beginnings developed a catalog rich in books about Fascism and Jewish persecution…

SZ I had an interest in those topics, felt that it was time for people to read and think about them. And I needed to find a commercially viable niche, something that would distinguish us. We started with some books specifically about Jewish persecution in Italy: two works by Fabio Levi (the director of Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi in Turin), L’ebreo in oggetto dealing with the enforcement of 1938 anti-Semitic laws in Italy, and L’identità imposta, the tragic story of Emilio Foà and his family during the persecution years; Michele Sarfatti’s Mussolini contro gli ebrei, which we have just reprinted in an updated edition; Giorgio Fabre’s L’elenco, about the censorship of Jewish authors during the’30s in fascist Italy, followed by many more. Fascism and the Shoah became the core of our catalog. We also have books on modern history (for example Luciano Allegra L’identità in bilico, a study on the Turin Ghetto in early XVIII century), philosophy and a variety of other subjects.

AC Besides promoting a whole generation of new historians your books on the Shoah in Italy combine intellectual rigor with a certain restraint…

SZ Both in treating the persecuted and persecutors we try to find the necessary reserve. While this was obvious in describing the victims, it seemed to me necessary for the persecutors as well.

AC Other than history and philosophy what are some of the other books have you produced?

SZ One of the most challenging projects was an Aramaic grammar book. To begin with, who is going to buy such a book? It was a hyper specialized volume, not an elementary grammar, so you can imagine my surprise when I realized it was selling better than most of our books.

AC Who was buying it?

SZ Like in a Mel Gibson movie… it was people who are convinced that only through Aramaic, one can get in touch with the ultimate truth of the Scriptures… Some times a book sells for the craziest reasons imaginable!

AC What do you think are your strengths as a publisher?

SZ I believe it is important —essential— to maintain good relationships with those who know how to do things well. Then as now, if I encounter someone who does something really well, I naturally assume a subordinate role. Not everyone can do this, and I consider it a real advantage.

AC From the start, your activities were not limited to Italy…

SZ I began taking and an exploratory trip to France, to meet publishers there. French, rather than Italian, is my first language. I began by contacting publishers and asking them who distributed their art reproductions in Italy and the answer was often “nobody”. And that is what got me started. In order to start my own publishing venture, to create a catalog, I needed to have some relatively steady income and distributing art reproductions was the first step.

AC Ok, how did you get the idea of framing the works yourself?

SZ In Italy, as elsewhere, framing was in the hands of skilled artisans, who had all the quirks, defects and idiosyncrasies of good artisans… I would ask them for something very thin, yet large in size and they would resolutely state: “impossible!” In other words, they would not do what I wanted, but rather they were confined to what they had been doing before. I particularly disliked when they would look at me and say: “we have never done it like that.” Confronted with all these “It will never work”, “That’s not how it’s done”, “we cannot do it”, I decided to make frames my self. Out of frustration, I started framing on my own.

AC When we were talking about your activity as a framer, what struck me is that you use the language of publishing.

SZ Yes. When I frame a work of art, I think of it as if I were conceiving the layout of a printed page. For me the two activities are almost the same: framing a picture is like producing a one-page book. Within a short time many people, galleries, and artist began to contact me, asking if I could frame and “layout”, their work as they had seen me do. I had transposed my knowledge from one activity to another, from publishing to framing and … surprisingly it worked!

AC Do you enjoy making frames?

SZ More than enjoy it, I love it! It’s a privilege: all kinds of marvelous work enters my workshop and it’s a privilege to be around them: everything from Renaissance paintings to contemporary works on paper. And further, it offered me the opportunity to meet and spend time with some of the great artists of our time. I am thinking of an extraordinary man like Giulio Paolini. I just completed a gigantic frame for Michelangelo Pistoletto. Over time there is real trust: in this case, Pistoletto’s assistant simply called me on the phone and gave me instructions and dimensions… Once trust is established, I find the space for invention and creativity. To be a frame maker one needs some understanding of art, great curiosity, and willingness to experiment. For me, curiosity comes from the publishing world, in publishing unlike in other fields your observation point is very wide. Trough books one thinks of the whole world. And for each book, you explore in depth a particular aspect.

AC Framing artworks also presupposes knowledge

SZ I will give you an example: I don’t just use glass, I know close to everything about the production of glass, and thus know exactly how to use it. My curiosity works in such a way that absolutely everything I do, each material I pick must have its own reason and justification. The similarities between bookmaking and framing are many and far-reaching. In publishing, people have been concerned for a very long time about durability and conservation. For instance, the Library of Congress from its inception has-been concerned with the optimal conservation of its books…. Surprisingly the art world has become concerned with conservation later on, with respect to the book world.

AC How do you define a book?

SZ A book is the wondrous and fundamental support for memory invented by man at a certain point in history. Being a container of memory, it can contain just about anything. If you think of the book as an invention, you realized that if it has changed so little over the centuries it is because it was such an incredibly well thought out invention, to begin with. The book is one of the high points of civilization, a beautiful and indispensable tool for transmission and preservation of knowledge. I recently discovered a little-known fact, that to me highlights the many dangers that the book has faced in its long history. Sometime in the Nineteenth Century a man whose name now escapes me thought that in order to prevent the risk of books going up in flames, they should be printed on asbestos… Imagine if his idea had caught on! It would have been the perfect involuntary assassination tool of unknowing readers.

AC The catalog of your publishing house speaks to the wide horizons of your interests: next to many titles about the Shoah and the persecution of Jews one finds many different topics…

SZ Over the years I have chosen to publish books that I felt were important, regardless of how close they adhere to any idea I had beforehand. In other words, I am not, in any way, sectarian. I did publish much on the persecution of the Jews but also on integration strategies, which I consider an important topic. Beyond the many books on and around the history of the Jews, I am proud to have published, for example, a marvelous book written by Vera Vigevani Jarach and Carla Tallone on Italian desaparecidos, in Argentina: Il silenzio infranto. I do not feel that, that with some books I am stepping away from my main focus, on the contrary, that everything in a sense is related to it, at least in my head.

AC Perhaps you are fortunate to have a mind that encompasses much and have the ability to find the deep connection between apparently distant topics…

SZ For me all my activities are one: all my books relate to one another. Further, when I move from publishing to making frames, I do not feel I am switching theme or activity, not really. As I said, for me an image in a frame, is a one-page book! I build the frame around the image as if I was making a book. And I do my very best to facilitate its readability. I have made both books and frames for many, many years now and the connection between them does not weaken at all over time, nor does my passion.

AC You describe yourself as a small publishing house, how many titles per year on average do you produce?

SZ With some fluctuation due to external factors, we do about 15-20 books a year. I would not be able to, nor want to make 200 per year. This is my dimension. In this business, one needs both a healthy dose of madness and a very down-to-earth realism. And some good luck!

AC I notice on your shelves a number of books for the blind and visually impaired.

SZ This is yet another chapter and one that is very dear to me. Over the years I began producing books for the blind. It all began with some of the same individuals with whom I was working on history books.

AC How did you start?

SZ One day, the historian Fabio Levi, a friend, a consultant and an author of our publishing house, suggested I made books for the blind. He himself teaches specific courses to people who can only read Braille. He asked me directly, “couldn’t we make books for the blind that have illustrations in relief?” To which —and this is my natural inclination— I responded “Why not? We will find a way”. That kick-started a new series of books in relief and stirred for me an interest in how shape and lines are perceived. Over time, we made remarkable books including a co-edition with the British Museum of the Parthenon friezes (in relief), and some extraordinary volumes with the Louvre in Paris as well as with major museums in Italy.

AC When did you start with books in relief?

In the early ‘90s.

AC Before you began, were there others producing “picture” books in relief for the blind?

SZ No, it was a brand new field. Of course, there was a rich production of books in Braille, but those contained only text, not images.

AC Can you read Braille?

SZ I had to learn. But again, having learned so many alphabets as a child, learning a new one was not a problem. After my initial talks with Fabio Levi, on a Friday afternoon, I stopped at a bookstore and picked up a book in Braille. By Sunday I had taught myself to read it. But mind you, I learned how to read Braille with my eyes, not with my fingers. Tactile sensitivity requires a completely different set of skills. To this day I read books for the blind with my eyes. Braille is a beautiful, rational, I would say, scientific system. It was born at two different times. The first attempt at a relief alphabet was –as most innovations– the result of a wartime effort. Around the end of the Seventeenth century, someone thought that an encrypted alphabet that could be read in any light conditions could be of great use during battle. But that first tactile writing system, using relief points was very difficult to read accurately. In 1821, the Frenchman Louis Braille, who became blind as a child, perfected the concept and devised a six-point tactile code, known simply as Braille, which is what millions of blind people still use today. In order to proofread and check the books we make, Braille is an absolute requirement.

AC In the same way, you had to learn Braille, I would assume your blind readers had to learn how to “read” the images in your relief books?

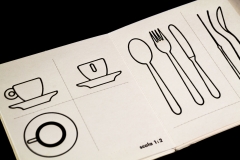

SZ Absolutely. Our first visual books for the blind where a sort of “how to” books: together with Tactile Vision – a non-profit institution that deals with tactile communication according to the principles of Universal Design – I inaugurated the series “Tacto”. I will show you one, called Oggetti e disegni. The challenge here was to teach a blind person to recognize a drawing of an object he already knows, in three dimensions. Every blind person knows what a clothespin is, but here they learn how to recognize a drawing of it. Each page has the object drawn from the front the side and the top. And the reader progressively learns, try it! Almost all drawings are in 1:1 scale (others bigger objects are drawn smaller than in real life, in order to learn how the scaling works) and as the reader gets familiar with it, we also show things that are inside and thus you normally can see, but not touch!

AC It’s a wonderfully ingenious, beautiful book!

SZ This one was designed by Rocco Rolli, an architect, who together with Fabio Levi directs Tactile Vision. My personal contribution to this volume was to devise a way to print and fold the entire book on a single sheet of paper. If I open it up you will see that there is no gluing or sewing involved, the pages are just folded from one single sheet.

AC What has working on books for the visually impaired taught you?

SZ It has shown me that in the effort to make something readable or understandable for the blind, we often reveal something about it, which is useful, and “new” also to those who can see. An example: when our book on the frieze of the Parthenon came out, a reviewer in the Times of London perceptibly wrote: “Finally we can understand what the Parthenon frieze was like!” He did not mention that it is a book for the blind. Why?

Any visitor to the British Museum finds the frieze hanging all around the walls of a room, and in that hanging arrangement, it is impossible to follow the stories that frieze narrates. Originally, in Athens, the frieze was hanging from the second order of columns; it formed a sort of a belt that surrounded the building. In order to see it, you had to move around the building following the narration. In truth, there were two separate visual narratives. They began in separate architectural points, which the visitor would follow as he visited the building. In other words, it was a more complex and experiential fruition than that of seeing it along the walls of a museum room, where you cannot follow the stories. Our book recreates the visual experience of seeing the frieze in its original location, like a movie. The reporter from the Times picked that up through this book for the blind. As I was saying even a sighted person learns a great deal from a book like this!

AC You must have spent a lot of time with the blind…

SZ As soon as I agreed to make books for them I wanted to get to know them: I have met some extraordinary people. I will share an anecdote which I find touching. One day Hoelle Corvest, who is in charge of accessibility at the Cité des Sciences in Paris, and is blind, came to visit me in my country home. Don’t imagine anything fancy, just a simple house in the countryside. Hoelle is not a kid, but she is very brave and independent. She travels alone a lot, gives conferences and leads a full life. We are having a good time, very relaxed, when a silly idea occurs to me (which happens often!) I tell her: “Hoelle, do you feel like driving?” and she immediately “I wish!” So I got her on a tractor and sat next to her. I started the engine and put her at the steering wheel, yelling occasionally “turn left, turn right…” We blissfully drove along in the open countryside where there were few obstacles and she could simply drive anywhere without real danger. What was wonderful was that for a moment she was in charge of a situation —driving a vehicle— where she had always been a passive passenger. She even balanced the tractor perfectly moving her weight when curving…

AC For those of us who can see, it is easy to define sight, but do the blind understand what they lack?

SZ The most beautiful answer I ever got from someone blind from birth (those who have lost their sight are a very different case) to my request to define sight was: sight is the ability to foretell things. When I pressed him to be more specific he told me: “All the way down that path, there are some trees. Seeing is the ability to know that, before walking the distance and touching them.” Beautiful no? Because of my experience in this field, last year I was invited to give some lectures on Museums accessibility in Japan, at National Children’s Castle (Shibuya, Tokyo), Yokosuka Museum of Art (Yokosuka, Kanagawa) and Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo.

AC How are books about Jews, art frames and the blind related?

SZ For me, they are all intimately related, as everything I do is. In essence they are intimately related. What all of them bring out of me is a desire to ask questions and then, sometimes, to find solutions or answers.

AC How would you describe yourself, briefly?

SZ I am both crazy— yes crazy! — and omnivorous. Or I could not have done all the things that we have been talking about.

AC What is an upcoming project that you would describe as stemming from your being crazy and omnivorous?

SZ I am planning to publish Primo Levi in Swahili! I have recently obtained the rights to If This is a Man, and am having it translated in Swahili, a Bantu language and the lingua franca of a large area of Africa, spanning from the Great Lakes region to Eastern and South-Eastern Africa. As you can imagine I do not know Swahili. This poses a number of difficult questions: not being able to check the translation personally I have to find experts who I trust, because as you know Levi’s linguistic precision, his deliberate use of each word, deserves and requires a great translation. We put the project into motion, but I cannot give you a publication date since too many factors don’t depend on us.

AC Centro Primo Levi would be honored to present the book in New York whenever it’s ready. What spurred your interest in Swahili?

SZ It began with another project, which was brought to me by Paola Gamna, a very kind and interesting woman. She works for an organization whose assumption is that Africa in addition to financial aid, also desperately needs cultural exchange. So we agreed to publish books (in Swahili) for African readers. Of course, such a project was expensive and not for profit…

When it comes to making books, I have a fundamental belief: you do not need to make money with a book but it is essential that it pays itself that is, that you do not lose money with it. This is a way to ensure that the process can continue, hopefully, perpetually. If making books does not sustain itself, either you are very rich—which I am not—or eventually it ends. And I want it to continue… I have been doing it for 35 years; I think I have learned a thing or two.

AC Were there publishers or book dealers in previous generations of your family?

SZ No, not in my immediate family. There was a Zamorani who published the daily Il Resto Del Carlino – the oldest Italian newspaper still in print – and owned Il Poligrafico Italiano, but I don’t think he was related to us. On my mother’s side, their last names were Iscaki and Nacamuli, there was a Jewish publishing house, but long before I was born. Under the Ottoman Empire, where printing in Arabic was prohibited, Jewish printers and publishers got around the ban by publishing in Hebrew, until around 1820.

AC Where in Greece was your maternal family from?

SZ In part from a town called Preveza in the North West, the rest from Athens. Our family is Sephardic but not from Salonika. At home, my maternal grandmother spoke Ladino.

AC Your paternal family moved from Italy to Egypt and back, can you tell me more?

SZ My grandfather Silvio, whose name I was given, was a member of the prosperous Jewish Community of Ferrara. He was sent to Egypt as the representative of Banco di Roma for Africa, and the family settled there. As early as 1932, the situation got worse as he lost his post as a consequence of his refusal to join the Fascist party. The hard times only got worse with Mussolini’s Racial Laws of 1938, but we were better off in Egypt that our relatives in Italy or Greece.

AC Did your parents keep in contact with their relatives in Europe?

SZ Only to a point, then the war broke out and contacts became impossible. In fact, we did not learn about the extent of the persecution and of the Shoah until after the war. My childhood in Egypt, though tough, was sheltered and often enchanted.

AC What is your relationship with religion?

SZ In Egypt, and later anywhere we went, there was no doubt that we were Jewish. I grew up in a secular Jewish family, and I mean, totally secular. I feel I have internalized their profoundly secular way of being. This, in no way, weakens my interest and relationship to Judaism, it simply exists on a different plane. Past childhood, I never attended a synagogue, I do not have that mental frame, and yet I adore rules, I want to know them and understand them all. Following them is another story.

AC Where in Egypt did you grow up?

SZ Mostly in Cairo. Eventually, we moved to Alexandria but both my parents were born in Cairo. They loved Egypt and never imagined being forced out. Yet after 1956, the Egyptian government began confiscating the property of Jews and eventually our family was among the thousands that were sent away. We choose to come to Italy, and we arrived in Genova. Soon my parent moved to Milano. My brother and I came to Turin where, given our parent’s difficulties, we were taken in by the Jewish Community’s orphanage. I settled in Turin and made my life here.

AC Can you describe some projects for the near future?

SZ I have one, which is symptomatic of both how I work, and of the sometimes bizarre fate of a book: we spoke about my past at Einaudi, I have just published Einaudiani in corpo minore, by Viola Lapiccirella. It is a wonderful light book about the people who worked as copy editors, proofreaders and back office technicians at Einaudi in the ’70 and ’80. The author, who was employed there, took down, collected and preserved fragments of conversations, drawings, sayings, memos and even dreams that describe, often ironically, daily life, reveries, emotions and concerns within the publishing house. The book was completed 35 years ago, at a time where Einaudi was undergoing painful and difficult transformations. At the time I did not want to publish a book that could be seen as critical of Einaudi at a time of crisis, so, in agreement with the author, I put it in a drawer where it remained until now. With the buffer of time, I think that now it can find its audience without creating any collateral damage.

As far as the Shoah, I am proud to announce an important book by Silvana Calvo (the title will be L’informazione rifiutata) that collects all the articles and memos about Nazi persecution and the final Solution which appeared in the Swiss press and other media (press agencies, radio, etc.) in those crucial years. It is remarkable how, contrary to popular belief, everything was known and written about in detail. I am convinced the book will help demolish what is left of the myth “we did not know anything about the camps”.

Another book I treasure is now going to press: Questa Legge non è in cielo (The Law – the Torah – is not in Heaven, from a verse in Deut. 30:12), it consists of a selection of lessons on Judaism by Franco Segre.