The Cinecittà Refugee Camp (1944–1950)

Courtesy of October Magazine. Spring 2009, No. 128, Pages 22-50, Posted Online June 19, 2009 (doi:10.1162/octo.2009.128.1.22), © 2009 October Magazine, Ltd. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Yes, they have sacked and destroyed it; the few remaining buildings accommodate only destitute, displaced families. But permit me to believe that on the highest wall, within the concealing yellow foliage, an empty movie camera continues to roll on, its lens focused on the clouds, waiting for a poet to find it, dust it off, set it finally before men and facts and, with neither fake models nor backdrops, expose it, al naturale , to our sorrow and our hopes.—Gino Avorio, “Schedario segreto,” Star I.1 (August 12, 1944)

The conversion of one of Europe’s largest movie studios, Cinecittà, to a refugee camp has always seemed an odd footnote to the chronicles of Italian cinema. However, as one recognizes its material and historical vicissitudes, its true magnitude, the duration of its existence, and the broader social and political forces that governed its development, the camp emerges as a stunning phenomenon and, in effect, a prime allegorical tableau of its time. Once confronted, the existence of the camp marks our vision of postwar film history, and, in particular, of Neorealism.

In that postwar era, the difficulty of obtaining shelter and basic sustenance presented a most urgent material problem, acknowledged as such and as a symbolic touchstone for the Italian imagination in the culture of reconstruction. It was in this spirit that Neorealism claimed to represent an authentic or pure reality of the street, of hitherto unseen urban or regional locations. As a movement, it defined itself against the perceived corruption of the studio, whose rhetoric of the colossal and whose elaborate sets had been co-opted and tainted by Fascism. Filming on location— turning one’s back to the studio as both institution and production space—was also in part a practical solution to the Allied requisitioning of Cinecittà.

It now appears, however, that aspects of this practice, aesthetic, and ideology— the central tenets of the Neorealist mythos—were also founded on concealed, or denied, vestiges of wartime events, on material circumstances and a human plight whose astonishing reality was unfolding within the space of the film studio itself. This space, categorically rejected by Neorealism, emerges, in the history to be recounted here, as a glaring reality, as urgent and as eloquent as—though perhaps more complex and multifaceted than—that sought by the Neorealists out in the street. The refugee camp—an entity meant to answer the basic needs of those who had survived the war but lost everything—was an eerily concrete counterpart to the artificial, fantastical world of the film studio. For like the film studio, it was, as well, a placeless place, set apart from the life outside. Compounding so many of the contradictions of its time, the Cinecittà camp emerges as a hidden, obverse figure of Neorealism. In refocusing a light long extinguished, one can project it back on the very culture of reconstruction that could not incorporate it within any of its official narratives. The archival documents and images, and the gaps that still plague the history of the camp, will join in a description of the overlapping uses and meanings, the physical and figurative implications, of a uniquely warped space, at once actual and phantasmatic, allegorical and cinematic.

Consider the cover of the June 16, 1945 issue of Film d’oggi (Film of today), a humble weekly paper of some eight pages, with Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti, and Gianni Puccini on its editorial board. The war in Italy was just over, although Rome had been liberated a year earlier. In September 1945, it would see the premiere of Rossellini’s Open City , the official launch of the Neorealist season.

The general outline of Neorealist history is familiar: turning their back on the Fascist studio production with its generic “white telephone” comedies, Rossellini and his colleagues turned to a more makeshift mode of production—part necessity, part ideology in this first postwar moment. Beyond the circumstances of production companies and studios in disarray, the decision to go out to film in Italy’s streets was motivated by a newfound interest in the chronicling of the everyday: key themes in this postwar, anti-Fascist vernacular are the urgent concerns of housing, sustenance, work, and importantly, the circumstances of children. Location shooting as Neorealist ethic and aesthetic—though so often joined with melodramatic fiction—was invested with the authenticating value of reportage, witness to hitherto unseen corners and aspects of Italy. Attention to contemporary urban or regional spaces in the wake of war was matched by a rejection of institutional modes of studio production and of its crowning symbol, pride of the Fascist era: Cinecittà.

There seems to be little trace of this on the cover of Film d’oggi , with its seductive glamour portrait of Vera Carmi from a film made that year in the tradition that never did die: Mario Soldati’s Le miserie di Monsu Travet (The misadventures of Mr. Travet), made by LUX, the single most active producer of the time.1 But already on the following page we find the Neorealist ethos articulated: an announcement on the part of the journal and the Catholic production company Orbis for an open competition on the theme “It Really Happened,” offering prizes of 5,000, 10,000, and 15,000 Lire (the equivalent today would be roughly 250, 500, 750 Euros respectively).2 “EVVIVA! [Hurrah] cries this man leaping in the air. I found what I have been looking for: a way to earn a nice sum of money by writing a letter, a postal card, or calling Film d’oggi . . . . EVERYONE can participate in this competition”: a competition whose jurors will include, the announcement says, Michelangelo Antonioni, Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti, Cesare Zavattini, and, among others, Alida Valli.

This was very much in line with Neorealism’s great call, so clearly voiced by its major advocate Zavattini, for the cinematic exploration of the everyday. “Our competition aspires to the truth of daily life,” specifies the announcement. “We want true facts that happened during the war. Report those to us as well as you can, without concern to embellish these facts, or to write them ‘well.’ This is the novelty of our competition. EVERYONE, from worker to housewife, can become an author, a film author, simply by informing us of a true story.” In his authoritative history of Italian cinema, Gian Piero Brunetta comments on this ad, noting the gap between the trust in the potential creativity of individuals that encapsulates the heart of Zavattini’s poetics, and the devastated structures of film production in this moment.3

Yet here was an immense and optimistic energy capable of evolving even in the absence of stable structures of production. The impoverished condition of the studios made a virtue of necessity. The institutional crisis was in fact to serve diverse production practices and ideological variants, even within Neorealism, though all claimed a more authentic witnessing vis-à-vis the apparatus of studio production. Zavattini’s call for a cinema of facts and the truth of daily life was itself more radical in theory than in practice, especially when one considers his own production at that time: the fairy-tale vision of children trotting away on a white horse in Sciuscià (Shoeshine), his work with De Sica in 1946, and, later on, their depiction of a band of the dispossessed flying off on broomsticks in Miracolo a Milano (Miracle in Milan , 1951).

Bittersweet films such as these, driven by earnest concern for those excluded from earlier Fascist fare, sought to smooth out the tensions of the moment, to establish a restorative narrative of affinities among classes and ideologies and across the ruined landscape: a redemptive vision exportable beyond Italy via the international dissemination of Neorealism. But even harsher Neorealist images, such as Rossellini’s Neapolitan rubble heaps or the open, vulnerable expanses of the Po delta in Paisà (1946), sought to forge an image of a purer Italy out of a “year zero” vision of reality—an authentic terrain to be found in the urban streets and in the regional landscape, sorted out from among the ruins of a more primal Italy.4 Indeed, the reconstruction of Italian cinema was predicated on a founding myth that would distinguish it from the fictions and spectacles of Fascism—the tales and sets of the colossals and other genres that were epitomized by Cinecittà, which functioned as the stateowned prime producer of escapist artifice and propaganda.

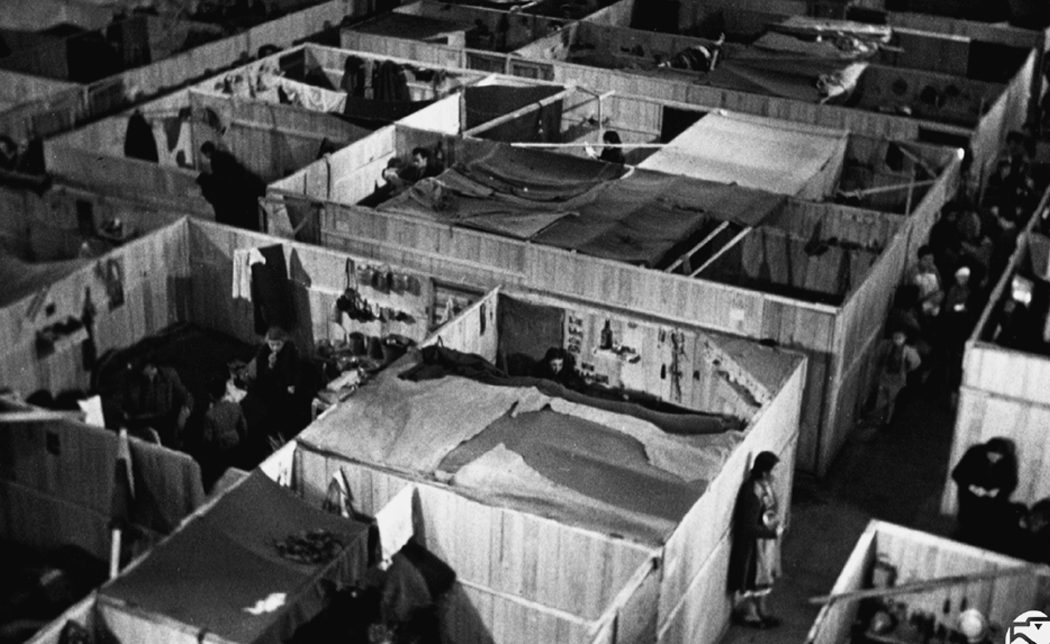

Leafing through Film d’oggi in this as in subsequent issues, one finds an odd hybrid: eloquent photographs of a hitherto unseen terrain. These images have the haunting familiarity of Neorealist iconography, yet we are not in any of its typical locales. We are in a unique site between bare postwar survival and ghostly fantasyland. This is the “desolate landscape of Cinecittà,” as one caption reads, and these are among the few photos documenting the grounds in the summer of 1945. They are accompanied by fundraising ads on behalf of the journal itself. The first announcement reads:

“Cinecittà is no longer the easy kingdom of Fascist cinema . . . [which] did everything possible to forbid the true anxieties and sufferings of our people access to the Cinecittà studios. Whoever had once dared show—between one shot and the next—a barefoot and destitute child, or a mother forced to beg, would have been struck like a felon by the Minculpop [the Fascist Ministry for Popular Culture]. Here they are now, these barefoot children . . . . Here are these mothers. They have been forced to storm the Cinecittà warehouses because they are now homeless, because their villages have been destroyed, and because Mussolini’s war made them lose their remaining pittance. Today the reality that the dignitaries of yesterday’s cinema did their utmost to exclude erupts violently in the old stately center . . . .

A serious lesson for our cinema, and to be kept in mind during the period of reconstruction. This is a commitment that the Italian cinema must assume before the Nation.

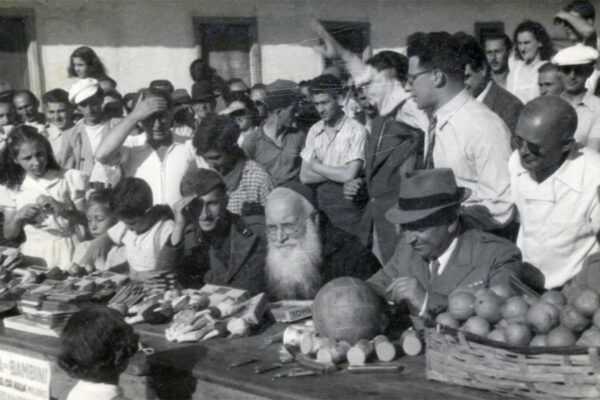

Meanwhile, in Cinecittà—not yet restored to the artists, the technicians, and workers of the Italian cinema—there are hungry children. This is why Film d’oggi has launched a fundraising initiative, the receipts of which—be it in cash or good—will be entrusted to the Hon. Zaniboni, High Commissioner for Refugees. Anyone can contribute.”

The public is asked to follow the example of the starlet of the magazine cover and other personalities from Gianni Agnelli and Carlo Ponti to Clara Calamai and Maria Michi, the new feminine face of Neorealism and contribute something for these destitute children, displaced in Cinecittà.5 The Neorealists on the board of Film d’oggi and sponsors of the fundraising initiative were doubtless aware of the destitution of the refugees that now populated the studio grounds.

The welfare of children was a widespread, grave problem everywhere: the Red Cross estimated that thirteen million children in Europe lost their natural protectors in the war.6 It was indeed a main cinematic theme in this era. But the Neorealists were to locate their raggedy little protagonists elsewhere. “Anyone can contribute” and perhaps “everyone” can make a film, yet for the children of Cinecittà, the Neorealists donated something—even before the starlets and the industrialists contributed their money, Zavattini had come up with 1 kg. of sugar—and went to work with their backs to the studio, and to the camp.

Filming on locations insistently removed from the Fascist studio and its sets thus entailed a certain blindness. They would not consider the possibility of locating in Cinecittà itself a reflection of the odd turns of reconstruction, wherein the urgent material and social ramifications of the war and its aftermath for daily life itself penetrated the very space of cinema. Neorealist culture could not tackle the ironic implications of a refugee camp being situated within the entity that was Cinecittà. One notes a certain degree of denial in the face of the extraordinary phenomenon of the camp. Both Giuseppe Rotunno and Marcello Gatti cinematographers who had been imprisoned for anti-Fascist activities and returned to work in Rome in this period—recounted on separate occasions how professionals in the industry were aware of the camp on the studio grounds, but could not face the “poveri disgraziati ,” the miserable wretches who now populated to capacity what had previously been a state-of-the-art movie studio.7 Film histories have been consistent with this attitude: the existence of the camp in Cinecittà is acknowledged, but with little detail and no analysis of this extraordinary six-year period, so closely considered in every other respect.8 It obviously did not fit into the mythos of Cinecittà nor into that of Neorealism. The refugees had been scattered over the globe, and many of those locals who lingered in the camps were the poorest of the poor and without communal support to preserve their memory. Thus avoidance, denial, or repression invested the refugee camp at Cinecittà with a certain psychic weight: it was an image that could not be confronted, an obverse reflection that could not be incorporated by Neorealism. But one must first briefly consider this setting in the period just preceding, as it brings us to this critical historical intersection. Read full article