A Historiographic Revisitation Based on OSS (Office of Strategic Services) Documents

Liliana Picciotto, Yad Vashem Studies, Vol. 48 (2020)

Read the full article in Yad Vashem Studies.

In his 2002 study of the SIS-OSS documents, Richard Breitman brought new elements to light and debunked erroneous beliefs concerning the chronology of the preparations for the October 16, 1943, roundup of the Jews of Rome. But a rereading of the same documents has further clarified certain details. First, in addition to being head of the German police in Rome, Herbert Kappler was also appointed to be in charge of security behind the lines for the Wehrmacht’s 14th Army from September 8, 1943, in the operations area under the command of Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring, with headquarters in Frascati, not far from Rome. This fact arises from Kappler’s statements during his trial in Italy in 1947. Furthermore, his constant contact with Kesselring, as well as the fact that military news was reported to Berlin from his shortwave radio in Villa Wolkonsky are proof of this. In addition, Kappler was sending radio messages not only to his direct superiors in Italy, Wolff and Harster, but also to Himmler and other RSHA offices in Berlin, especially Office VI/E, which dealt with foreign espionage and was directed by Schellenberg.

The fact that Italy was not among the countries whose citizens were exempted from deportation, according to the list distributed by Heinrich Müller on behalf of Kaltenbrunner on September 23, 1943, indicates that the Italian Jews would soon be part of the Final Solution. Moreover, in the last week of September 1943, Kappler received a preliminary alert from Berlin of upcoming anti-Jewish actions to be organized by SS-Hauptsturmführer Dannecker, who had been sent specially by the RSHA. The preliminary alert related to roundups of Jews that were going to take place throughout German-controlled territory, including Rome but not only Rome. On September 26, three weeks before the roundup, Kappler demanded a 50-kilogram gold ransom from the Jews, despite the fact that he was well aware that they would soon be arrested. Clearly this was extortion, and not a diversionary tactic to help the Jews, as he later claimed.

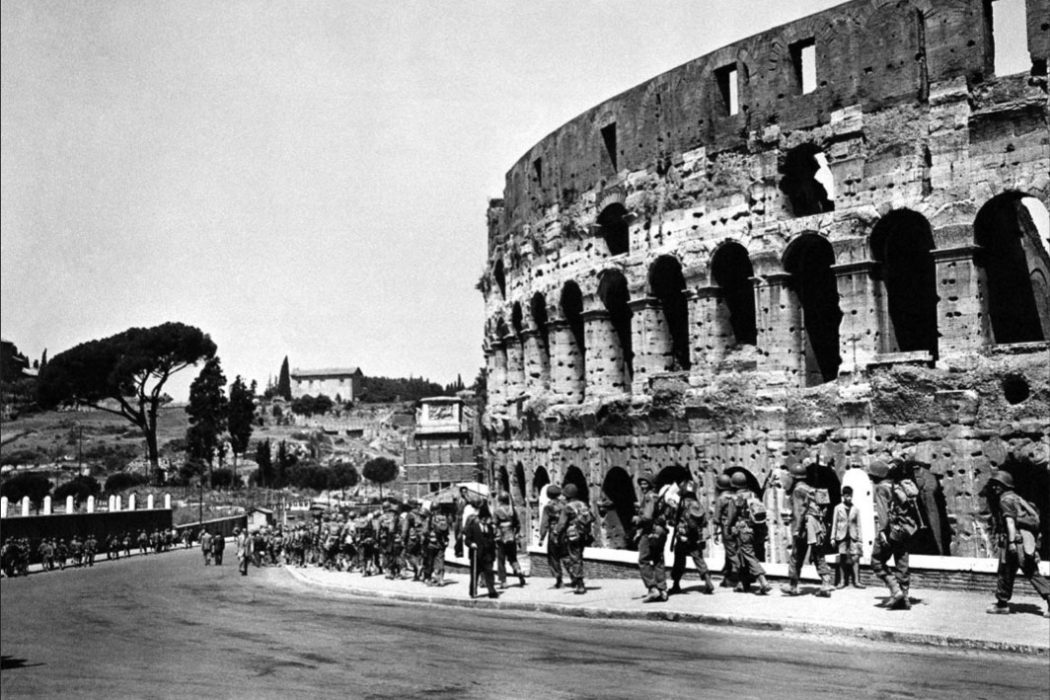

The anti-Jewish actions were actually supposed to begin in Naples, at the southern border of German-controlled territory, on October 1, but this plan was thwarted by the decision to pull the German army back out of southern Italy due to the advance of the Allies from south to north. The roundup of the Jews of Rome was the most shocking action, but only the first of its kind. Müller planned to send Dannecker to Italy to carry out surprise roundups and deportations in all the major cities; after Rome, Florence, Siena, Montecatini, Bologna, Genoa, the Ligurian Riviera di of Ponente (western Riviera), Turin, and Milan were to follow. This is an important point, which disputes the notion that the cessation of roundups in Rome after October 16, 1943, was due to Vatican intervention. The departure of Dannecker’s SS detachment from Rome was simply the continuation of a planned, premeditated program, not the result of any external pressure.

As to the idea of forcing the Jews to perform physical labor on the city’s fortifications instead of deporting them — as proposed in Moellhausen ’s October 6 and 7, 1943, telegrams to the foreign minister, and mentioned by Kappler to his superiors at the RSHA on the evening of October 6, and by Ambassador von Weizsäcker to Ribbentrop on October 17 — actually came from Kesselring, who had demanded and imposed this same labor service on the Jews of Tunisia ten months earlier. The difference in ideas about how to treat the Jews, then, was not between the RSHA’s central office and its men in the field, or between the RSHA and German diplomats in the field, but between the RSHA and the Wehrmacht.

As for the Vatican’s attitude toward the German roundup and the deportation of the Jews, this question would require a separate study, especially since the Vatican Apostolic Archive has now been opened to scholars (since March 2, 2020). We would like only to point out here that in the message of Foreign Minister Ribbentrop (via von Sonnleithner and via von Thadden) to Consul Moellhausen, he not only ordered him not to interfere in the mopping-up matter, but also mentioned the Mauthausen concentration camp as the destination of the Jews of Rome. While we know that the destination of the West European Jews was the Auschwitz camp, the place of extermination, one explanation could be that, due to the presence of the Pope in Rome and his lukewarm reaction, the Roman Jews who were originally destined for Mauthausen were deported by the Nazis to Auschwitz like everyone else. An alternative, but less probable interpretation of the mention of Mauthausen is that Ribbentrop wanted to keep Moellhausen in the dark about the existence of the Auschwitz camp.

Preparations for the anti-Jewish action in Rome were lengthy and laborious, and involved collaboration between Kappler’s and Dannecker’s men, and also with the Italian authorities, who provided lists and addresses of the Jews living in the city. Some twenty policemen helped create lists for each neighborhood in Rome and type thousands of sheets with the six points of the instructions to be left in the homes affected by the roundup. These instruction sheets, hastily typed by several people, contain misprints and errors and occasionally slightly differ one from another. With the collaboration of the Italian authorities, Dannecker and Kappler also needed to inspect various places for temporarily concentrating the thousands of expected victims; they could not know in advance that the best place would be the building of the Military Academy on Via della Lungara. Likewise, the supply of food for the deportation train was requisitioned by the prefect of Rome, who was responsible for ensuring the city’s food supply.

The train left from the Tiburtina Station, one of Rome’s secondary depots, with railroad cars supplied by the Italian state railways, and with Italian drivers and stokers who took shifts until they reached the Italian- Austrian border. In this whole story the only gestures of human decency came from the Italian population — neighbors, acquaintances, friends, and shopkeepers — who, in the face of the emergency that morning of October 16, 1943, opened their doors to hide and protect terrified Jews. The fact that the Germans intended to arrest 8,000 Jews and in the end arrested and deported “only” 1,020 is a tribute to them.