A Convert’s Tale: Art, Crime, and Jewish Apostasy in Renaissance Italy.

Tamar Herzig. A Convert’s Tale: Art, Crime, and Jewish Apostasy in Renaissance Italy. I Tatti Studies in Italian Renaissance History Series. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019

Katherine E. Aron-Beller (Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

Citation: Katherine E. Aron-Beller. Review of Herzig, Tamar, A Convert’s Tale: Art, Crime, and Jewish Apostasy in Renaissance Italy. H-Judaic, H-Net Reviews. August, 2020.

Tamar Herzig is Tenured Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History at Tel Aviv University, Israel. She has authored articles on topics such as the prosecution of heresy and witchcraft, Renaissance demonology, premodern reform movements, and female spirituality. Her first book, Savonarola’s Women: Visions and Reform in Renaissance Italy, was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2008. Another monograph,”Christ Transformed into a Virgin Woman”: Lucia Brocadelli, Heinrich Institoris, and the Defense of the Faith, was recently published by Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura (2013). In 2012, Herzig was elected member of the Young Academy of Israel, founded by the Israeli Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

Katherine Aron-Beller is lecturer of Jewish History at the Rothberg International School of the Hebrew University and at Tel Aviv University. She received her PhD in early modern European Jewish history from the University of Haifa in 2002. Her areas of expertise are early modern Jewish-Christian relations, the early modern Inquisition and the history of anti-semitism. Her books include Jews on Trial: The Papal Inquisition in Modena 1598-1638 published in 2011 by Manchester University Press; an edited book with Christopher Black called The Roman Inquisition; Centre versus Peripheries (Brill, 2018) and most recently Christian Images and Jewish Desecrators: The History of an Allegation 400-1700 which is under review at the University of Pennsylvania press. Her current project is a study of two holocaust memoirs, written by a German Jewish survivor, one written in 1945 and the second in 1995.

Tamar Herzig’s meticulously researched and superbly written book offers an intriguing view into the dramatic life story of Salomone da Sesso, better known as Ercole de’ Fedeli (ca. 1452/57-after 1521). A renowned Renaissance goldsmith in northern Italy, Salomone lived for approximately thirty years as a Jew. In 1491, he converted to Christianity, as did his wife and four children, after he was accused of sodomy; this was half a century before the first foundation in Italy of institutions that specialized in the instruction of converts from Judaism and Islam. Were it only a biography of the colorful life of one of the most important virtuoso artists of the time, it already would have been a valuable contribution to Italian social history, art history, Jewish history, and Jewish/Christian relations. To her credit, Herzig, a specialist in the religious, social, and gender history of early modern Italy, provides a more ambitious and richly textured panorama of the wider effects of Salomone’s life as a Jew, as a Christian, and as a goldsmith, in relation to his family members, his patrons, associates—both Jews and Christians—and the Renaissance culture and society in which he lived.

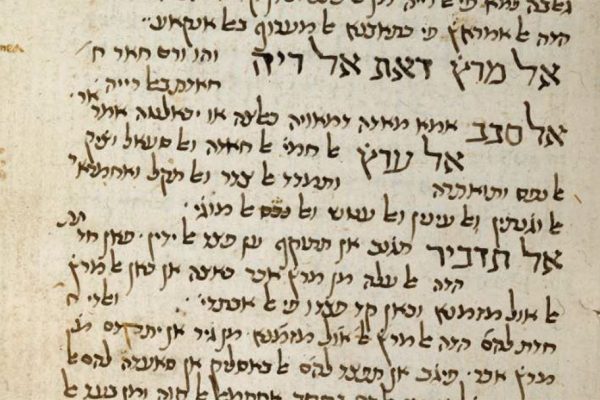

Using a “paper trail,” as she calls it, of documents—chronicles, detailed letters, missives that prominent Renaissance women and men dictated to their scribes, inventories, payment registers, testaments, guild regulations, acts of endowments, and notarial records from archives in Mantua, Bologna, Ferrara, Rome, Florence, and Modena—Herzig offers a patient and thorough explanation of every stage of Salomone’s life (p. 7). She consistently reflects on events from different angles, coming near to a total history of his life. What is missing and tantalizing for both her and her readers are Salomone’s thoughts on his conversion, faith, and beliefs. Since virtually no personal writings have survived, much of his inner life remains obscure. His prosaic speech at his own baptism was probably not his own work and a letter of 1504 to Isabella d’Este did no more than excuse his delay in delivering her bracelets.

Herzig provides a detailed insight into and analysis of the “scintillating material culture” that Salomone created and for whom (p. 9). Though the relationship with his patrons—Eleonora of Aragon; her husband, Duke Ercole d’Este; and their children, Duke Alfonso I d’Este and Marchioness Isabella d’Este, and their respective spouses, Lucrezia Borgia and Duke Francesco Gonzaga —was an unbalanced one of dominance and subordination, it was also one of interdependence, especially for the female fashionistas who anxiously awaited the arrival of their glittering ornaments. These included Lucrezia Borgia’s various pieces of jewelry; Isabella d’Este’s maniglie (bracelets), which were to decorate her bare arms in the summer, and a gold lid Salomone made for her perfume pomander; a “Queen of Swords” for the military leader Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI; and an enameled gold chain and a large gold button commissioned for Lucrezia’s brother, Giovanni Borgia, as a gift for the king of France, Francis I, in the hope of attaining a position at court. When these creations were not completed on time, or when Salomone cheated his patrons of money, imprisonment hung over his head irrespective of whether he was a Jew or a Christian.

The question at the center of Herzig’s study is why did Salomone convert? People are always products of complex societies, prejudices, and challenges, and Salomone is obviously no exception. Herzig follows the theories of Paola Tartakoff that Jews by and large converted to extricate themselves from trouble or because they were pursuing social and economic advantages (often illusory).[1] Herzig believes that Salomone only converted because he had fallen out with the Mantuan Jewish community, been accused of sodomy, and probably been sentenced to death. It should be noted that only convicted Jews were in the unique position of possibly reducing their sentence for grave crimes such as sodomy by converting.

But had Salomone convinced himself that converting would also bring financial success? As Herzig confirms, there was a surge in the rise of Jewish baptisms in northern Italy at this time. Northern Italian lay rulers, even more than churchmen, took the lead in endorsing Jewish baptism, offering Jews work, and protecting them from their enemies. Nevertheless, this was not universal, as Salomone found out when his supportive patrons died. Without this cushion, neophytes were left on their own to deal with the lingering shadows of their Jewish past. Salomone’s lack of success, after 1505, when Duke Ercole d’Este died confirms the precariousness of life for converts after baptism.

Herzig examines the consequences of Salomone’s conversion on his immediate family. She enters the minds of each and every one of them, offering an understanding of their behavior and reactions to Salomone’s dramatic act and its substantial effect on their lives. His wife, Eleonora—who is only named in the sources once she was baptized—converted in order not to lose the custody of her young children. Salomone’s oldest daughter, Caterina, undertook a life of celibacy in a Dominican tertiaries’ house, thanks to Duke Ercole d’Este’s patronage. Salomone’s daughter, Anna, was selected to become a donzella, one of the female attendants of Lucrezia Borgia. Here she was provided with an education, clothing, accommodation, a dowry, and a “suitable” husband.

Not surprisingly, the first half of A Convert’s Tale focuses on Salomone’s Jewish life. In the second half of the book, Salomone has become the Christian Ercole. Here we witness Ercole’s efforts to fit into that society although in many ways he remained an outsider in both communities. The powerful last chapter, “Baptizing the Jews,” brings the two halves of the book together; it meticulously describes the dramatic baptism ceremony of Salomone and his oldest son, performed by the Bishop of Ferrara, Bartolomeo della Rovere, nephew of Pope Sixtus IV. This ceremony, which took place in the Cathedral of St. George, Ferrara, on Sunday October 9, 1491, was intended to provide “a spectacular manifestation of Christianity’s triumph over Judaism” (p. 92).

The first half of the book is divided into two parts. In part 1, “The Virtuoso Jew” (chapters 1-5), Herzig focuses on Salomone’s formative years, his professional development as a Jewish goldsmith, and his relations with Jews in Bologna and Mantua until his falling out with community members of Mantua in 1491. Coming from a relatively affluent family of moneylenders, Salomone was a quintessential outsider. He broke away from the Jewish profession of moneylending, possibly having gained knowledge of precious metals and gems when he had assessed their value for securities for loans. He spent his early life in Florence and then moved to Bologna with his mother and siblings after his father’s death. He married a daughter of the banker Zinatan Finzi in about 1478, and the couple had four children (two boys and two girls) before their conversion to Christianity (and an additional three daughters when living in Ferrara as Christians). By 1487 they had moved to Mantua since it provided better opportunities for Jewish goldsmiths; Salomone was apprenticed to a Christian master goldsmith, Ermes Flavio, in the service of Francesco Gonzaga, the Marquis of Mantua. Here he became recognized as a talented goldsmith and became aware of Flavio’s professional privileges as a master craftsman—a title that could not be bestowed on Jews in Italy at the time. In 1489 he decided to move with his family to Ferrara to benefit from a more stable income as a goldsmith rather than depending on specific commissions. If his life had continued in this vein, Salomone, as a gifted goldsmith who created new artistic trends, could, as Herzig maintains, have pursued “a successful artistic career without having to compromise his religious beliefs” (p. 29).

Salomone had already accumulated serious debts in 1485, and continued to act irresponsibly, gambling or indulging in illicit pleasures with men or women in taverns, and then demanding financial support from his Jewish relatives. He also sometimes cheated his patrons of sums of money to pay these debts, thus making them unsympathetic to his subsequent plight. When, in March 1491, a case of blood libel surfaced and a baby girl was found mutilated and murdered in the center of Mantua, the Jews of that city—some of whom Salomone had already alienated—accused him of being an informer and of incriminating certain Jews for the murder. Believing him to be a threat to their collective welfare, the Jewish community did not hesitate to denounce him to the Gonzaga rulers.

Part 2 of the book (chapters 6-9), which is labeled “Apostasy,” begins by studying the Mantuan Jews’ accusation against Salomone for sodomy and other transgressions (although Salomone’s processo before Ferrara’s criminal court is not extant). It suggests that members of the Jewish community did not show solidarity in the face of Christian authorities: indeed, they did not hesitate to lay information before princely courts that implicated fellow Jews in capital crimes. Among these was sodomy, and here Herzig concentrates on homosexuality in Renaissance Italy: how the crime could be lodged against certain Jews by their Jewish adversaries, how sodomy was particularly associated with goldsmithery in Renaissance Florence, and how Christians responded to the allegation. She then describes Salomone’s conditional pardon, which was granted by Duke Ercole, under pressure from his wife Eleonora of Aragon who wanted Salomone to continue creating dazzling jewelry for her. The second part of the book ends with Salomone’s baptism.

Part 3 (chapters 10-15), “A Family of Converts,” begins Ercole’s long and tortuous attempt to achieve a desired assimilation in Christian Ferrara. This, I believe, is the most impressive section of the book as Herzig comes into her own, on more confident terrain of Christian history, and elucidates the consequences of conversion not only for the goldsmith but also for his two daughters and two sons in the first fifteen years after their conversion. Ercole assumes the honorific appellation of Master Goldsmith and continues to work in Ferrara. Continuing to rely on local Jews for redeeming pledged objects meant that the neophyte maintained contact with the community despite his new existence. As a Christian goldsmith, he produced at least four reliquary tabernacles as part of large-scale, expensive, and prestigious ducal projects, but his anomalous status, as a former Jew who had aroused suspicion of dishonesty and deceit, prevented his full integration into Christian society.

Herzig also follows the trials and tribulations of Ercole’s children. One senses how much easier it was for the next generation to assimilate into Christian society. Ercole’s oldest son, Alfonso, began making various pieces of jewelry for Lucrezia Borgia, was chosen as the goldsmith responsible for the safekeeping of the duchess’s jewels during her trip from Rome to Ferrara, and by 1504 was working alongside his father as a qualified goldsmith. Ferrante, Ercole’s younger son, was also trained by his father and became a full-fledged member of his workshop. Caterina, Ercole’s oldest daughter, at the late age of twenty-two, was placed in a monastic house in order that her father need not secure her a dowry. Herzig believes that Caterina, like her mother, would probably not have converted on her own initiative. Whether she was able to acclimatize and be accepted in the nunnery is questionable. His second daughter, Anna, as mentioned above, entered the court of Lucrezia Borgia. It was from this time that Ercole’s health began to fail, due to the harsh working conditions of his workshop.

Part 4 (chapters 16-20), “Between Jews and Christians,” tracks Ercole and his family from 1505 and the death of their princely protector, Ercole d’Este, to 1522. No longer employed as a court goldsmith, the Fedeli workshop suffered the consequences of continuous warfare and the stormy years of the Italian Wars (1494-1530), the failing health of Ercole, unrealistic promises for the date of finished commissions, and recurrent epidemics. This was a difficult period for everyone. Ercole again chose to resort to shady means to ensure an income, which suggests that he was indulging in gambling or other disreputable pursuits, or just had poor administrative and managerial skills. Faced with financial calamity, particularly after the untimely death of Lucrezia Borgia in 1519, the goldsmiths suffered through unannounced visits of the dukes’ officials and threats of incarceration as well as actual imprisonment for both Ercole and Alfonso. Without a strong matronly patron demanding glittering works of art, Ercole’s commissions ran dry and only a few works were commissioned by Alfonso d’Este during the last years of Ercole’s life. Conversion had therefore been no guarantee of financial security. One wonders, then, whether Ercole’s experiences as a high-profile goldsmith actually prevented others from taking the same path.

The wealth of insight and perspective that Herzig brings to her monograph makes A Convert’s Tale a huge and important contribution to the study of apostasy, micro-history, and religion. Her research inspires her readers to continue at least one line of inquiry, which is to find out how many Jewish women across northern Italy were baptized and entered nunneries. I certainly would have appreciated a list of archives and primary sources at the back of the book to ensure easy access to Herzig’s trail. Nevertheless, Herzig’s work will stand at the forefront of research on the conversion of Jews to Christianity in Renaissance Italy for many years to come.

Note

[1]. Paola Tartakoff, “Testing Boundaries: Jewish Conversion and Cultural Fluidity in Medieval Europe, c. 1200–1391,” Speculum 90, no. 3 (July 2015): 728-62.