Michele Sarfatti, The Jews in Mussolini’s Italy – From Equality to Persecution, The University of Wisconsin, 2007

Often overshadowed by the persecution of Jews in Germany, the treatment of Jews in fascist Italy comes into sharp focus in this volume by Italian historian Michele Sarfatti. Using thorough and careful statistical evidence to document how the Italian social climate changed from relatively just to irredeemably prejudicial, Sarfatti begins with a history of Italian Jews in the decades before fascism–when Jews were fully integrated into Italian national life–and provides a deft and comprehensive history from fascism’s rise in 1922 to its defeat in 1945.

“This rich and compassionate study of the plight of Italy’s Jews combines vivid narrative with scrupulous historical accuracy.”—Booklist

“Michele Sarfatti has challenged and effectively demolished the myth that Italian fascism was simply aping Hitler’s Germany in its creation of the racial laws against the Jews. He describes the independent genesis of Mussolini’s racial policy and its distinct character.”—Alexander Stille, author of The Sack of Rome and Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families under Fascism

Il Duce’s Own Idea, Alessandro Cassin, The Forward

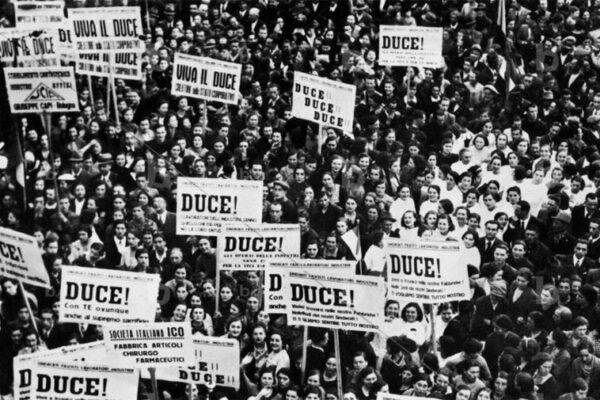

In 1934, Benito Mussolini famously declared that “there has never been antisemitism in Italy.” A mere four years later, after abandoning his Jewish mistress of 27 years, he passed his infamous racial laws.

Michele Sarfatti’s “The Jews in Mussolini’s Italy” explains this startling reversal, providing new interpretations of an often misunderstood aspect of Holocaust history. The most comprehensive work to date, this expanded English edition is destined to become the definitive text on the subject. Sarfatti, director of the Centro di Documentazione Ebraica Contemporanea in Milan, chronicles the history of Italian Jews from Mussolini’s rise to power in 1922 to his downfall in 1945.

Based on newly discovered documents and an abundance of statistical data, the book demonstrates that, contrary to popular belief, Mussolini’s policies toward the Jews were independently conceived and implemented, and not — as some have argued — a late concession to Hitler’s war against the Jews. Despite Il Duce’s alliance with Hitler, “only” about 7,000 Italian Jews (16.3% of the Jewish population) died in Nazi death camps. Moreover, documented instances of Italians risking their lives to save Jews abound—a fact that reinforced the perception of Italians as “brava gente” (“good people,” the kind who helped preserve Jewish lives).

Based on newly discovered documents and an abundance of statistical data, the book demonstrates that, contrary to popular belief, Mussolini’s policies toward the Jews were independently conceived and implemented, and not — as some have argued — a late concession to Hitler’s war against the Jews. Despite Il Duce’s alliance with Hitler, “only” about 7,000 Italian Jews (16.3% of the Jewish population) died in Nazi death camps. Moreover, documented instances of Italians risking their lives to save Jews abound—a fact that reinforced the perception of Italians as “brava gente” (“good people,” the kind who helped preserve Jewish lives).

The book draws a three-dimensional picture of Jewish life in Fascist Italy in all its variety and nuanced complexity. There were Jews who at first adhered enthusiastically to Mussolini’s program, others were among the first to organize antifascist activities, as well as many who hoped to remain neutral. The range of activities of Italian Jews extended from academics and professionals all the way to shop keepers and panhandlers. What emerges is a heterogeneous population that professed varying degrees of religious identity and many different levels of assimilation.

Jews were so well integrated into Italian society that by 1922 when Mussolini took power, they were in every branch of government, including the military, and were represented all across the political spectrum. But antisemitic sentiment in Italy, as Sarfatti shows, can be traced far back. As he argues, the leftovers of the medieval Catholic anti-Judaism provided fertile grounds for anti-Jewish nationalism, which in turn fed Fascist antisemitism. The rise of an antisemitic ideology escalated with Italy’s colonial war in Abyssinia of 1935. The Fascists first developed the concept of “Difesa della razza” (“defense of the race”) in dominating the black population of the African colony. At this early stage, this doctrine had parallels only in Nazi Germany and was completely absent in the rhetoric of Fascist movements, from Spain to Hungry, Romania and Poland.

Among the author’s many original claims, he maintains that the seeds of antisemitism were present in the Fascist regime since its inception, though antisemitism was not yet official policy. With a multitude of documented examples, the book follows the antisemitic crescendo in both official political discourse and practice. As early as 1934, the office of the Interior Ministry pressed for the replacement of Ferrara’s mayor: “It has been brought to our attention that the local citizenry feels displeasure to have a mayor of the Israelite religion at the head of the city’s administration. Therefore, it is desirable that he be replaced with a Catholic mayor.” In 1938, the Italian dictator passed and enforced the racial laws, in many respects even more restrictive than anti-Jewish legislation in Nazi Germany, and Italy became an officially antisemitic country. Sarfatti stresses that Mussolini was never pressured by Hitler regarding racial policies. Italians on the whole did not protest the laws until their lethal consequences became clear. By 1943, the Fascists began confiscating Jewish property and rounding up Jews for deportation, and abruptly many of those who had not protested against anti-Jewish laws rushed to save Jews.

Sarfatti’s meticulous reconstruction of the events of late 1943, when both the Nazi and the Fascist were arresting Italian Jews, clarifies the joint efforts of the two regimes. Although his collection of data sometimes interrupts his narrative, the book is a compelling read and a major contribution to a more sophisticated understanding of antisemitism in Fascist Italy.