A new book will be presented at Bookhouse on March 18th.

Jews and State Building: Early Modern Italy, and Beyond. Edited by Bernard Dov Cooperman, Serena Di Nepi, and Germano Maifreda, Leiden-Boston, Brill: 2025

This volume aims to shed new light on the history of the Jews in Italy between the early modern period and the emergence of a unified Italian state, explicitly placing Jews within the history of the state-building process. It seeks to reconsider Jewish history systematically by stressing the relation of Jews and the state and to trace how Jews and their communities were reshaped in the early modern period.

A conference on “Jews and State Building in Early Modern Italy” was held May 5-7, 2019, at the University of Maryland in College Park and Johns Hopkins University. This was the second gathering within a larger project that also included an earlier international conference on “Sabbatanism in Italy and its Mediterranean Context” (Sapienza – University of Rome, January 20-22, 2019) and a later one entitled “Imagining the Renaissance, Defining the Jews” held in Jerusalem on January 19-21, 2020, just before the outbreak of the pandemic.

In 2019, two scholarly meetings (University of Maryland, Johns Hopkins, and University of Rome La Sapienza), sought to explore forms of cooperation, imitation, exchange, alliance, and interaction between Jews and Christians in early modern Italy. The research project was aimed at challenging the traditional paradigm that looks at the history of Christian-Jewish interactions only through the prism of anti-Semitism. We have tried to demonstrate strategies of coexistence between different religions and cultures, strategies that helped to shape early modern European political and social history and were instrumental in defining what has been defined as modernity.

Within this larger framework, our volume aims to shed new light on the history of the Jews in Italy between the early modern period and the emergence of a unified Italian state, explicitly placing Jews within the history of the state-building process.

Traditional scholarship on the history of the Jews in Italy has operated within an “emancipatory” model: the peninsular city-state system, it was assumed, had simply yielded to the forces of national unification. In this approach, the condition of the Jews was framed within the ongoing dialectic between the progressive forces of modernity and the regressive forces of religious and political oppression. The Jews had been ’emancipated’ by the triumph of the liberal and secular state.

In recent decades, the history of Jews in Renaissance Italy has undergone both gradual development and radical change. This historiographical field was once focused on local history and informed by an underlying Burckhardtian and positivist approach. It is now characterised by an increasingly sophisticated appreciation of Hebrew cultural dynamics, a globalising approach to Jewish identity, a sensitivity to spatial and material historical ‘turns’, a greater appreciation of the dynamics of Jewish mercantile and financial activity, and an increasingly nuanced understanding of Jewish interaction with non-Jewish culture and society. These changes – which invested both Jewish and general-Italian historiography – have rendered the traditional approaches we have mentioned above, if not wrong, at least outdated.

We now know that early modern Italy is no longer seen as static or dominated by the stranglehold of foreign occupation and crippling ecclesiastical repression. Rather, the peninsula is seen as the site of a complex process of state-building, a multi-local set of experiments and negotiations that shaped state power in modern Europe as a whole. Consequently, it is now also time to rethink the established narrative and to reconsider Jewish history systematically within the new approach, by exploring systematically the relationship between Jews and the state, and to trace how Jews and their communities were reshaped in the early modern period.

This book challenges traditional approaches to Jewish issues by opening up, for the first time, broader political dimensions at both the Italian regional and transnational levels. Our volume addresses the administrative and judicial treatment of Jews by the state, the political autonomy and organisation of Jews within the state, and the relationship between local Jewish and state identities, all with the aim of reorienting the field of scholarship.

Isabella Lazzarini proposes here an innovative view of the political history of late medieval Italy, highlighting the complexity and variety of the Italian world and surveying the mosaic of kingdoms, principalities, signorie and republics against a backdrop of wider political themes common to all types of state in the period.

Traditionally, scholars have approached early modern state formation by focusing on the growth of the state apparatus (bureaucracy) and the increasing centralisation of administration in the eighteenth century. The fifteenth to seventeenth centuries have been treated as a preparatory phase of the modern state.

Francesco Benigno shows us that, from the 1980s onwards, this approach came to be seen as inherently anachronistic in its tendency to always look for precedents for what was to come. Benigno also stresses the need for historians to address the relationship between the periphery and the various centres of political, economic, religious, military and judicial governance.

Bernard Dov Cooperman discusses how the nineteenth-century approach to pre-modern European Jewish history (Leidens- und Gelehrtengeschichte—a history of suffering and [rabbinic] scholars) gave way slowly and awkwardly to a broader vision of Jewish social and cultural studies that integrated broader elements within Jewish society. Agency was discovered in the Jewish community organization (kehila), though this was still studied largely through rabbinic rulings. But the richness of Jewish and state archival sources surviving in Italy allow us to understand that, paradoxically, the Jewish community was as much the product of the demands made by the state as it was the expression of any consistent and authoritative internal system of Jewish autonomy.

The contradictory and crucial encounter between Christian Italian States utilizing and theorizing finance as a political instrument, and the Jewish Italian political representations of Jewish-Christian society as a complex relational system only partially representable in economic terms, is a key moment in the building of European modernity.

Giacomo Todeschini investigates here the degree to which the ghettoization of the Italian Jews actually coincided with a growing dialogue/conflict between Christian economic-political rationality and Jewish political thinking.

The “place of minorities” in the political processes of the late medieval history of Europe is also at the center of the chapter by Pierre Savy. This subject has long been underestimated in the historical literature: perhaps not in the sense of an explicit and self-conscious underestimation, but rather simply in the sense that minorities have been neglected, invisible and therefore absent from the dominant historiographic narratives.

Renata Segre shows us that the creation of the Venetian ghetto came as a surprise to the Jews, who for a short while deemed it a temporary measure that they would easily and quickly overcome. Some distinctive features, and the spirit behind the creation may explain its duration, and make the difference with the typical Italian ghettoes, first erected forty years later.

Vincenzo Selleri works here on fifteenth-century Kingdom of Naples, where iudeca was a term that in the documents produced both by the royal and the municipal officers indicated either the Jewish community, or the space that the community inhabited. The location of Jewish quarters, the distribution of Jewish real estate, and state and local legislation suggest that, originally, iudece were not spaces meant for the segregation of Jews, although in time they might have become exclusively Jewish quarters. In rare instances cities even tried to be “freed of Jews” by denying them the right of residence.

Focusing on hitherto unexplored sources relating to the Papal States and Bernardino Campello – the apostolic commissioner responsible for enforcing the 1555 papal bull Cum nimis absurdum in the Campagna and Umbria – Serena Di Nepi examines the birth of the ghettos from an innovative perspective. It is a long and complex story that brings together individuals, communities and states, and that shows how difficult it has been to govern the machine in the peripheries, where other logics can prevail.

There is a causal link between the political developments of a state and its juridical and fiscal attitude towards the Jewish population. This was particularly evident in the Italian peninsula, which, in the late middle ages and in the early modern period, as

Davide Liberatoscioli shows here, was a prolific laboratory of political diversity. The expression universitas Judaeorum, as a juridical term, took a central position in the development of the dynamic relationships between Jewish populations and ruling powers.

Katherine Aron-Beller concentrates on the 1581 Pope Gregory XIII’s bull Antiqua iudaeorum improbitas that authorized and expanded inquisitorial jurisdiction to include practising Jews. The pontiff was conscious that many Italian rulers had decided to tolerate Jews rather than expel them because of the economic benefits that they provided. Italian ghettos – the forced enclosure of Jews – had only been erected in four states at this time.

Justine Walden’s essay examines the references to Jews found in letters exchanged among Medici court members between ca 1540-1590 to understand the developments that undergirded the Livornina, the 1591-93 decree which not only invited Jews to settle in the Tuscan port of Livorno, but guaranteed them multiple protections and afforded them freedom of religious worship. Epistolary references from the 1540s onward reveal the Tuscan state’s growing awareness of the power held by diasporic Sephardim in Ottoman lands, the court’s reliance upon Jews for information and goods from the Levant, and that it considered invitations to diasporic Jews as against potential Jewish emigration to Ottoman-ruled territories.

The last section of this book focuses on the challenges of “modernity”. During the 18th century, in particular, the political balance established in Italy at the time of the Counter-Reformation collapsed. The understanding between the civil and ecclesiastical authorities was shaken as a result. This was the moment when the States began a slow process of emancipation from the control of the Church, as evidenced by the weakening of the controlling role of the Roman Inquisition.

Marina Caffiero’s chapter shows that the increasingly frequent conflicts and the establishment of new balances of power had considerable repercussions on the Jewish world, which became an instrument of this confrontation.

Finally, we have the formation of an Italian nation-state, which created new problems and opportunities for its citizens. But what did it mean for the Jewish minority in the new, unified Italy? How could Jews combine and redefine Jewishness and “Italianness” in a radically new political, economic and legal framework?

Germano Maifreda argues that the economic-historical perspective can make a significant contribution to shedding light on these transformations and offering new perspectives from which to read the modern Jewish experience in the Western world.

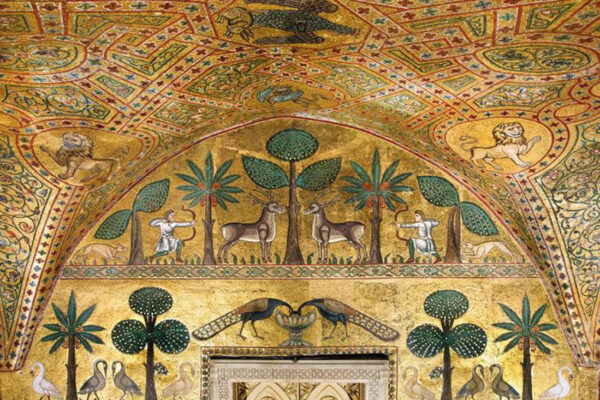

The preparatory work for this volume was financed by the European Union-Next Generation EU, within the PRIN 2022 project Spatializing Jews and the Economy. Towards a Digital and Dynamic Atlas: People, Business, Artifacts in Global Italy (14th-20th centuries), prot. 2022EHLWYE, CUP G53D23000190006; principal investigator Germano Maifreda, chief of the University of Rome unit Serena Di Nepi. Image: Il re Salomone, c. 1525 by Maestro de Becerril.