Ugo Castelnuovo Tedesco (Florence, 1890- 1974) was a renowned criminal defense lawyer, and a fervent antifascist who served time in prison and in confino (Fascism’s system of internal exile) for his political views and actions. He was the elder brother of composer Mario Castelnuovo Tedesco. Among his friends were prominent antifascist figures such as the Rosselli brothers and Gaetano Pieraccini, who became Florence’s mayor after the liberation of the city. Ugo and his family fled Italy in 1944, finding refuge as Jews and anti-fascists in Switzerland. There, Ugo taught Law and Criminal Procedure at the University of Geneva. Later, he served as vice president of the Italian National Lawyers’ Council and, like his father Amedeo before him and his son Michele after him, he sat on the board of the insurance company La Fondiaria. A fervent advocate of literature and culture, he was president of the prestigious Florentine cultural organization Gabinetto Scientifico e Letterario G. P. Viessieux. His writings include L‘udienza è tolta [The Hearing is Adjourned], a volume of reflections on the legal profession and his experiences as a criminal lawyer, which was published by Vallecchi in 1960.

This text was to be published in the September 1943 issue of the journal Argomenti but the publication was suspended in August 1943. It appeared in an anthology edited in 1979 by Saveria Chemotti under the title Argomenti. Firenze marzo 1941-agosto 1943.

I was released from Le Murate three days ago.

In my section, there was an inmate from Prato – the nicest man, who had been “in” for the past fourteen months for some textile deal gone wrong. He knew all the ins of the prison rules and guards to perfection – and, at the beginning of my stay, from window to window, with a certain complacency about his own erudition, told me the whole history of Le Murate. He was the eldest and most distinguished in our yard; thus, we political prisoners called him “Mr. President.” The others, who were on more intimate terms with him, called him by his last name: Cipriani, or in its Florentine contracted form: “o Cipria!” From him, I learned of Le Murate’s conventual origins: a former Benedictine nunnery, whose residents were called murate, walled in, due to the rigidity of their seclusion. With his tales, he reminded me of Caterina de’ Medici and Caterina Sforza’s affairs. He explained how the old convent had been converted into a prison, expanded little by little, one building after another until it achieved its current layout. But I must confess that, with all the tribulations that I’ve had, Cipriani’s historical reconstructions have slipped my mind, and to keep things as straightforward and simple as possible, I will just say that Le Murate is Florence’s prison.

When I arrived, after they took my fingerprints and gave me, to clean my hands, a tiny rag so filthy with sludge that it actually made them dirtier than before, the registration official taking down my personal information asked me: “repeat offender?” I modestly answered no, but he didn’t seem convinced, as if he recognized my name somehow. So I explained to him that, perhaps, it rang familiar because I had been a lawyer for nearly thirty years and had come to Le Murate infinite times, but not exactly as an inmate.

In truth, this is my only and actual remorse from my time spent in jail. Before, when I went to Le Murate as a lawyer, I handpicked my cases: with suspicion, with sophistry; to defend only just causes, or, at the very least, beautiful ones; driven by an artistic and professional meticulousness in which, only now, do I recognize some not so pure specks of vanity. Only now, having experienced firsthand what one suffers in prison, do I understand that, at the moment when human beings are destined to this terrible seclusion, are locked up and treated like animals, defending any one of the inmates is an act of justice, and any cry from the heart is a work of art.

Back then, I visited Le Murate with a certain haste and indifference, trying to see as many defendants as possible in one go, talking only for a few minutes and focusing on the strictly necessary arguments of their defense. Then I would leave, my heart at peace, and go back to my family and life. Now I know what blindness and selfishness hid in the ease of my detachment from those poor devils I left behind; who, perhaps, felt the desire, without really knowing how, to tell me of their many physical and moral hardships; who, perhaps, more than a defense, needed a little love. Instead, they were taken back to their empty cells, which, in turn, must have looked even emptier. Not one of them, in thirty years, ever blamed me for not having visited them freely, without a purpose, only to offer them the comfort of a human face and a human word addressed solely to them and not to their case. So, when the Ministry Inspector interrogated me about a crime that I had not committed, I told him I had another one to confess. It was, precisely, this human wrong of mine, of having crossed paths for thirty years with creatures in pain, who harshly endured what I was enduring now, and that I had not given them, each of them, enough of my own soul.

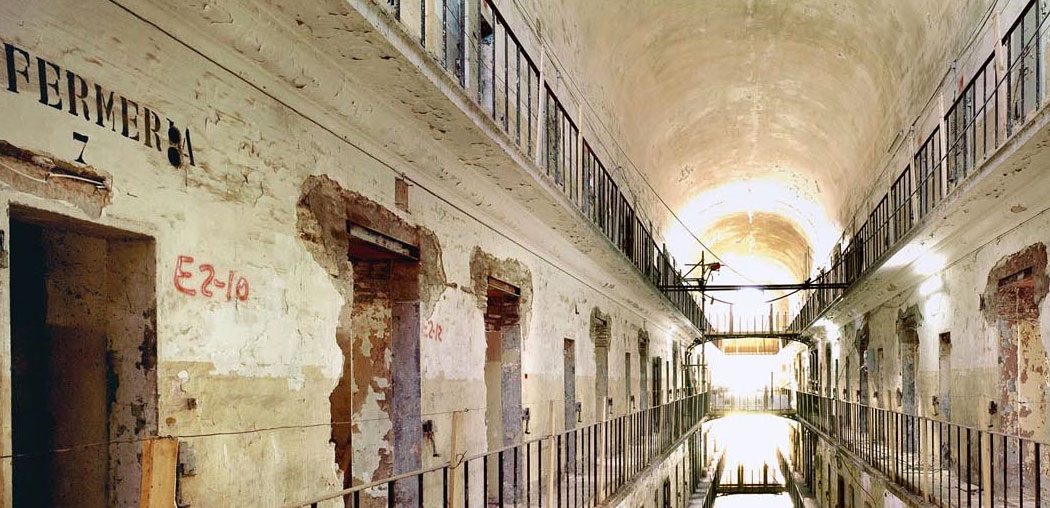

It’s a fact: people in jail don’t fare well. In the last twenty years, many roads have been paved, and many buildings have been built. My utmost desire would be for a Ministry of Justice to come with me, for five minutes, to see for real (and not in a staged visit) the indescribable pigsty in which men are kept. Men! There are dog grooming shops where we wash puppies, remove fleas, brush their hair. Why should human beings, even if guilty (and they can be innocent!), be kept in conditions that would arouse disgust and mercy for an animal? You have to see, with your own eyes, those miserable cells where it’s impossible to breathe, those straw beds black with filth, those walls, those ceilings, those windows, those doors crawling with vermin, that one bowl that must be used both to eat and to wash (to eat the soup they hand out in the morning, and that must last all day, and, at the same time, to wash our face, our teeth, our hands, everything); you have to see, with your own eyes, that bedpan that remains in the cell even when it’s full, that pair of rough sheets that are assigned at the beginning of the month and must last for the entire month, that water mug and pitcher that one must use to drink and to wash (it’s summer, stifling hot, if I drink I don’t wash, if I wash I don’t drink); you have to see, with your own eyes, the few tubs we all yearn to visit to rinse ourselves, in turns, one thousand of us, one after the other, sick and healthy alike, and those cubicles where they send us “to walk,” in a tiny slice of yard, (eight feet on one side and three across) just to take a few breaths of fresh air and glance at the sky (for instance, as it was in my case, between 1:30 and 2:30 pm in the heat of July.)

It should all be cleared, demolished, rebuilt – the stones and the spirit of our jails. Not out of a basic sense of elementary hygiene, but out of a greater awareness of social dignity and more substantial respect for the human being.

The best, cleanest, worthiest part of these “jail establishments” are, without a doubt, the inmates: even the worst ones. When somebody comes along dressed a little better, those inside immediately sniff him out as a “newbie” and ask him at once: “political or ordinary?” I’ve a vague idea – but I could be wrong – that the guards prefer ordinary prisoners. But not the inmates. Out of those intuitions that are so immediate and certain in our people, even the scrappiest of prisoners, the most hardened of criminals instinctively create a hierarchy of where they fit in among the others; it is the truest of hierarchies because it is not imposed by anyone else but based solely on each person’s free assessment and spontaneous inspiration. Perhaps, in ordinary prisoners, each of us sees, in silent resentment, the dire circumstances of our families; perhaps, in political prisoners, we intuitively recognize the selfless commitment to an idea. I will never be able to recount with sufficient emotion and gratitude, not only all the respect, but the love, solidarity, moral support, and human charity that came my way, day after day, cell after cell, from a few familiar figures and countless total strangers, during my stay in prison.

In some cases, I managed to catch a glimpse of their faces. The man who brought my clean laundry (the laundry that came from home, with its itemized list in my daughter’s handwriting) told me that he had seen her, that she looked serene and cheerful. I thought of the high school exams she had passed after witnessing my arrest with her very own eyes, and that, on the Italian written test, out of 170 students, she, along with two others, were the only ones to choose the literary subject instead of the political one, previously drafted and brought from home. (Ah, Italy’s youth, how they have educated you in the last twenty years!) At that moment, her proud and courageous smile appeared in my cell like a ray of light, and I, in that smile, found renewed hope and energy.

But the majority of my prison mates, I never saw. This is one of the peculiarities of this strange community, where we live together for months on end without ever meeting, and where, a bit at a time, we share our lives, our stories, those of our dear ones, and get to know the most delicate intimacy of our inner selves, without ever laying eyes on each others’ faces. We stay there, glued to window bars, like sad monkeys, and we speak into the void without ever seeing a human face. That is perhaps what I missed the most: the certainty of a known face, the gaze of another human’s eyes, like our own, the sight of an actual mouth speaking actual, living words.

And yet, during those interminable days, we talked and talked. The conversations found a pace of their own, with a courteous regard that resembles etiquette, and patient tolerance, which is observed even by the most heinous of the inmates. When two prisoners speak to each other, nobody interrupts them; be it a discussion about music or poetry or one about the “version” of the facts about some stolen goods. Yet, the whole yard withdraws and respects this extreme sense of freedom that emerges between two obscure brothers who have been deprived of almost all others. At some point, the two go quiet, and two more begin to speak; and then two more. It is not my place to judge whether, at times, with my sole presence, I might have infused courage and faith into my companions; and yet, how many times did I hear my name, and how many kind words were delivered to me by some windy thread across the emptiness of the yard.

One voice always warned me when the rounds (“the buzz”) were about to start; another kept me informed, night after night, of the guards on duty (“the cat” is nice, “the cat” is mean). From all sides, I was asked whether I needed something: a cigarette, a lemon, a piece of bread, out of the little they had; and, if I was in need of anything, the “mule” immediately went into action: a complicated system of strings, tied together I don’t know how, from outside, and through which, at some point, I saw appearing, between my bars, the sweetest and most beautiful of things: a stranger’s offering. In recent times, the “mule” had stopped working; otherwise, I would not speak of it; nevertheless, a hundred times a day, from someone passing by my cell in the corridor, or calling me from the window, I kept receiving, from heart to heart, a single greeting, a simple encouragement, of those that infuse life back into life… “C’mon, avvocato. Patience. We’re all on your side.”

Three voices, among all, have remained especially dear to me. One is the voice of a professor from Genoa, exquisitely learned and kind, who, at twilight, when the nostalgia for all things familiar hit us hardest, with the horror of those nightly visits about to start —every three hours, keys banging against the metal doors, chains rattling, lamps shined into our eyes —cheered me up with a refrain of prudent wisdom: “how this will end, I don’t know, but sooner or later, it will!” Then Cipriani pitched in, affirming with purpose, as Florentines do: “I know how this’ll end!” And he was right! We bid each other good night, one by one – I mean, one voice after the other – and we lay down to sleep, almost always without actually getting to sleep. But, at 9 pm sharp, right after the Great Bell of Palazzo Vecchio beat its last toll, I heard a stranger’s voice, with a Sicilian accent, shouting every night from a faraway cell: “Avvocato Castelnuovo, good night: keep your spirits up!” I never knew who it was; I never saw him; I can only thank him like this by remembering him and all the good he did me. He was my conscience; he was my family; he was my country. It felt like the synthesis of everything: a comfort that went beyond me, that meant to say for all, near and far, present and future: “When you suffer through no fault of your own, when you suffer for your own Country, keep your spirits up!”

29 July 1943

Ugo Castelnuovo Tedesco