A century before global Jewry reached out to Ethiopia’s community, a researcher named Jacques Faitlovitch sowed the seeds for a future ingathering.

An odd sculpture recently appeared on the Tel Aviv University campus, following a complex, transcontinental, logistical operation. It was designed in London, assembled in Italy and shipped by sea to Israel. The artwork consists of metal pipes emerging upward from the ground, splitting, and winding around two palm trees. “This expresses continuity and departure,” said the sculpture’s designer, Israeli-born architect Ron Arad, in a phone call from London.

The sculpture is a memorial to Ethiopian Jews who left their homes between 1977 and 1985 for the exhausting, traumatic journey to Israel. The trek took them from Ethiopia to Sudan, and across mountains, deserts, rivers and forests; they faced hunger, thirst, illness, harassment and arrest before winding up in refugee camps

About a fifth of the people – about 4,000 – died on the way. The others were flown or taken by sea to Israel in several stages that climaxed with the Operation Moses airlift. Six years later, in Operation Solomon, an additional 14,500 Ethiopian Jews were brought to Israel. This month is the 20th anniversary of that operation.

The statue was commissioned and financed by Michael Benabou, a French-Jewish businessman and a member of the French Friends of Tel Aviv University, which provides scholarships to Ethiopian-Israeli students. Two years ago he decided it was time to dedicate a memorial to these students’ community. “It is a tribute to the operation that brought them to Israel, commemorates their suffering, and expresses hope for their future,” he said by phone from Paris.

Another artwork commemorating the Ethiopians who died on their way to Israel stands at Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. A ceremony is held there every year on Jerusalem Day, the official memorial day for the Ethiopian Jews who perished on the way here. The Jerusalem sculpture was initiated by Uri Rada, chairman of a volunteer association commemorating the Ethiopian Jews; his mother was one of those who died on the way over in the early 1980s. Now he is waging a campaign to collect the names of those 4,000 people and inscribe them on a memorial stone.

Lost brethren

The relationship between the Jews of France and Ethiopia began a century ago, with one man who devoted his life to the latter community. The new sculpture stands opposite Tel Aviv University’s central library, where a small, crowded room on the second floor stores the archives of that man, researcher Dr. Jacques Faitlovitch, who died in 1955.

Only a few people outside the Ethiopian Jewish community know who he was. His Tel Aviv house has been abandoned for years. However, thanks to Faitlovitch’s research, visits and diplomacy, Ethiopia’s Jews underwent a revolution of consciousness that eventually led them to Israel.

“At first it is hard to believe that a white man, Polish no less, was the one who went to Africa to tell the Ethiopian-Jewish community that they were his lost brethren,” said Wasihun Achenefe, a 26-year-old Tel Aviv University law student who works with the Faitlovitch archives.

Faitlovitch was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1881, and visited Ethiopia for the first time in 1904. He received a grant from Baron Edmond de Rothschild to “look for black Jews,” newspapers reported at that time. The European scholar, who had studied at the school for oriental languages at the Sorbonne in Paris, astounded the Ethiopian emperor, Menelik II, with his fluent command of the country’s languages, and told him that the Ethiopian Jewish tribes were connected to white Jews elsewhere in the world.

Several years later, an interview with him was published in Warsaw’s Hebrew newspaper Hatzfira. “The first time I came, in 1904, they did not want to believe that I, too, am a Jew, and only after a while did I manage to prove to them that there are many more Jews in the world. Since then they have wanted to be closer to these Jews,” the article quotes him. When asked about that mission’s chances of success, he said: “I am sure of it. So sure that I have decided to devote my life to this cause.”

There are various theories about the community’s origins. Some people consider them descendants of the 10 Lost Tribes. Others believe they are descendants of Ethiopian Christians and idolators who accepted Judaism.

Faitlovitch was not the first Westerner to visit the remote Jewish community known by two names: Beta Israel, the term the community uses for itself, and Falasha, a derogatory term meaning exiles, that is commonly used in Ethiopia.

In 1769 a Scottish explorer, James Bruce, set out on an expedition around Ethiopia that included a visit to the Jewish community. Prof. Joseph Halevy, who eventually became Faitlovitch’s teacher, was the first Jew to visit the community 100 years later. But he failed to “draw” the community closer to world Jewry, and passed the baton to his pupil.

Faitlovitch tried to tell the Jews and the rest of the world about the community, launching diplomatic efforts in their name. He also tried to convince the community to change its religious practices to conform with rabbinic Judaism. Therefore he opened two Hebrew schools, one of them in Addis Ababa, to teach Judaism and the history of the Jewish people and also to preserve the community’s own religious traditions. And before World War I, he sent some of the community’s youth to study in Europe and Palestine so they could share their knowledge back in Ethiopia.

“Education was supposed to crack the community’s isolation and link it to world Judaism, in order to reconnect this branch that has been forgotten for so long, preserve it, revive it and arouse it out of its apathy,” he said.

On his second visit to Ethiopia, in 1909, he met 15 Jewish families in the village of Adi Shohu in the northern district of Tigre. He related his experiences in his book “Masa el Hafalashim” (Journey to the Falasha ; published by Dvir in 1959 ): “When we arrived, the Falasha greeted us enthusiastically. Despite the pouring rain they came out in festive clothes to greet us. They invited us to huts they had built for us and hurried to finish preparing the Sabbath meal … After the work was done, all the Falasha gathered in the synagogue for Friday night services. The prayer lasted all night long with occasional breaks to eat … the Falashas occasionally sang in religious exhilaration … I told them the Jewish people wished to convey friendship and told them my trip’s goal.”

Faitlovitch fought Christian missionaries, who sought to make the Jewish community adopt the “real” religion. He would give the boys Hebrew names and organize bar mitzvahs for them, causing the Protestant missionaries to complain about “the French missionary.”

In a Gonder suburb, he met converts from Judaism. “They said they were happy to see me in their country again and said they wanted to return to their forefathers’ faith. They told me: ‘Your presence encourages us and we all want to return to being Falasha – do not forget us, we are Falashas too.'”

In his book, Faitlovitch says they were forced to abandon Jewish practices. “The Falasha artisans were compelled to undertake all sorts of forced labor for senior officials … so they could not avoid working on the Sabbath and eating forbidden foods. Resistance was punished severely. One man who refused to desecrate the Sabbath was chained and detained until he agreed to work on the Sabbath.”

Years on the road

Faitlovitch became a legend in Ethiopia and many people respected him. Pictures in his archives show him in white clothes and a black hat in order to impress his audience during addresses in Ethiopia. “He told us stories about Jerusalem and the Jewish people. No one wanted to listen to the priests’ stories, only to Faitlovitch’s,” recalled one of his students, Yona Boagle. But others say he treated some of his pupils resolutely and patronizingly.

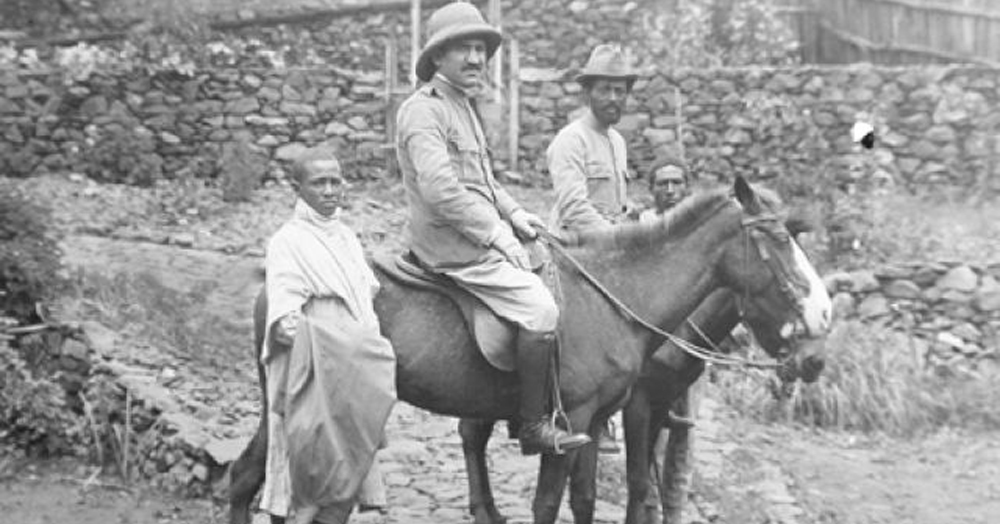

Faitlovitch spent years traveling, and had no permanent residence until his final years. Between his visits to Ethiopia, which he traversed on a mule, he traveled the world to raise money for the Falasha Jews, helped by his contacts with diplomats and important Jewish institutions.

Faitlovitch continued with his strenuous work even in the face of tough diplomatic circumstances. For example, he returned to Ethiopia in 1942, shortly after the Italian occupation of Ethiopia ended and amid reports of the destruction of European Jewry. He said at a farewell party in Jerusalem, “According to reports that have reached me from Abyssinia (Ethiopia ) … life is returning to normal … The government is willing to oblige the Jewish exiles, expelled from their European states by the Nazis … and allow entry to any Jewish group willing to settle in Abyssinia.”

His good contacts with senior Ethiopian officials gained him two government jobs. In 1942 he was appointed inspector general of the Ethiopian Ministry of Education, and two years later he became an adviser at the Ethiopian Embassy in Cairo, a job he held for two years. It was an odd position for a Jew: representing a Christian African power in a Muslim capital, Haaretz wrote after his death.

In 1947 Faitlovitch started to actively promote Ethiopian immigration to the Land of Israel. In a letter to the Joint, he said the destruction of European Jewry made it the Jewish people’s duty to help the Falashas move to Palestine. “With the millions of Jews who were just now exterminated, we cannot afford to ignore the potential source for Jewish manpower,” he argued.

Faitlovitch was the first person who brought an organized group of young Ethiopian Jews to Israel, 30 years before Israel waged a big operation to bring them over. In 1955, 12 Ethiopian Jews came to the Kfar Batya youth village, near Ra’anana, to study Hebrew and Judaism. As part of the agreement with the Ethiopian authorities, and despite the youths’ desires, they had to return to Ethiopia to serve as teachers there.

Faitlovitch spent his final years in a home on Tel Aviv’s Vitkin Street, where he kept his collection of books and rare manuscripts, including hundreds of books about Ethiopia, dozens of manuscripts in Ethiopian languages and a historical archive of Ethiopian Jewry. After he died in 1955, his widow gave the house to Tel Aviv’s municipality, and it served as a public library. “I want to hope that the Faitlovitch House, which I gave Tel Aviv’s municipality … will be a source of information for all the people who go to Abyssinia and for its Jews,” his widow, Miriam, wrote in Haaretz in 1959.

Twenty years later, the municipality moved the library to Tel Aviv University. About a decade ago a doctoral candidate, Haim Admor, started restoring its contents. “It is the community’s sole historical archive and is a rarity in the world,” he said. Hopefully, Tel Aviv’s municipality will pick up the gauntlet and restore the Faitlovitch House. As a first step, it could put up a sign commemorating him.

The relationship between the Jews of France and Ethiopia began a century ago, with one man who devoted his life to the latter community. The new sculpture stands opposite Tel Aviv University’s central library, where a small, crowded room on the second floor stores the archives of that man, researcher Dr. Jacques Faitlovitch, who died in 1955.

Only a few people outside the Ethiopian Jewish community know who he was. His Tel Aviv house has been abandoned for years. However, thanks to Faitlovitch’s research, visits and diplomacy, Ethiopia’s Jews underwent a revolution of consciousness that eventually led them to Israel.