Plans for Mass Jewish Settlement in Ethiopia (1936-1943)

Pankhurst was born in 1927 in Woodford Green to left communist and former suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst — already 45 years old — and Italian anarchist Silvio Corio. Sylvia Pankhurst had been an active supporter of Ethiopian culture and independence since the Italian invasion in 1935, and Richard grew up knowing many Ethiopian refugees.Sylvia was a friend of Haile Selassie and published Ethiopia, a Cultural History in 1955. In 1956, she and Richard moved to Ethiopia.He began working at the University College of Addis Ababa, and in 1962 was the founding director of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies. He also edited the Journal of Ethiopian Studies and the Ethiopia Observer.

Pankhurst left the Institute and his professorship at what had become the University of Addis Ababa in 1976 after the death of Haile Selassie and the start of the Ethiopian Civil War. He returned to England, where he became a research fellow with the School of Oriental and African Studies and the London School of Economics, before working as librarian at the Royal Asiatic Society. He returned to Ethiopia in 1986, where he resumed research with the Institute.[4] He has published numerous books and articles on a wide variety of topics related to Ethiopian history.

Pankhurst led the campaign for the return of the Obelisk of Axum to Ethiopia. It was re-erected in Axum in 2008. For his efforts in this, he was given the honorary title “Dejazmach Benkirew” by the Union of Tigraians of North America.

Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in the autumn of 1935, and the development of anti-Semitism in both fascist Italy 1 and Nazi Germany, led to a number of plans for the mass settlement of Jews in Italian-occupied Ethiopia and other parts of the fascist colonial empire. The object of the present article is to trace the progress of such plans which have thus far been inadequately studied.

One of the initial results of the fascist invasion of Ethiopia was to create a significant amount of interest in the Falashas, or Ethiopian Jews, on the part of a number of Italian Jews. This remarkable Jewish community in the highlands of Christian Ethiopia thus received its share of attention in the Italian press. The Italian journal La Nostra Bandiera for example published an article on April 15, 1936, entitled ” Con Toccu-pazione di Gondar si pone agli ebrei italiani il problema dei falascia,” i.e., ” With the occupation of Gondar Italian Jews are faced with the problem of the Falasha,” while the still somewhat influential Italian Jewish weekly Israel, of Milan, carried an informative article on ” I Falascia” by the Jewish scholar Carlo Alberto Viterbo in its issues of May 7 and 14. 2

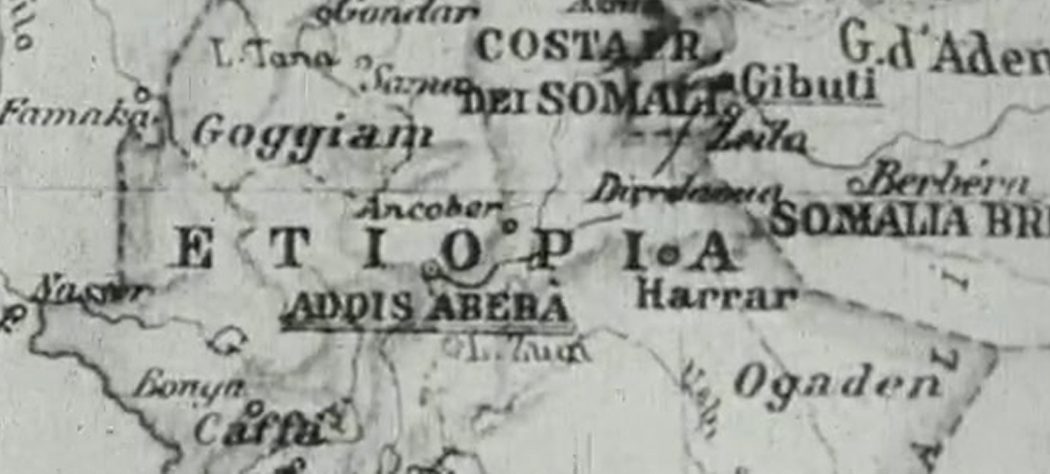

Early in June the Italian Jewish organisation, the Unione della Communita, made contact with the Italian Minister of the Colonies, Allesandro Lessona, who agreed that it could concern itself with the welfare of the Falashas, and establish branches at Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa. Viterbo, a councillor of the Unione, and Umberto Scazzocchio, another member of the organisation who was then resident in Asmara, were subsequently entrusted with investigating the position of the Falashas on the spot. Viterbo left Italy for East Africa at the end of July, and was received on August 22 by the Italian Viceroy, Marshal Graziani, who permitted an Addis Ababa branch of the organisation to be officially recognised by decree on September 19, the idea of forming a similar branch at Dire Dawa being, however, abandoned.

The Jewish communities under discussion were admittedly small, it being reported at about this time that that of Addis Ababa numbered 54 Falashas, 61 Jemenite Jews, 25 Italian Jews, and 38 Jews from other European countries. 3 Viterbo was subsequently nominated commissar to the Jewish community in Addis Ababa, and was responsible also for the Jews at Jibuti in the French Somaliland Protectorate. He later visited Falasha communities in northern Ethiopia, taking with him the noted Ethiopian scholar, Professor Tamrat Emanuel, who was the director of the Falasha school which had been established in Addis Ababa prior to the war. 4

While Italian Jewish organisations were thus active on the largely social or cultural front the fascist State began to put out feelers to foreign Jewish communities with a view to possible co-operation in the field of settlement in occupied Ethiopia. As early as May 14, 1936, only nine days after the Italian occupation of Addis Ababa, the director of the Austrian branch of the semiofficial Italian insurance agency, the Instituto Nazionale delle Assicurazioni, Robert Auer, who was himself a Jew, raised the matter in Vienna with one of the Zionists, Dr. E. M. Zweig, in the presence of Schischa, a representative of the Austrian fascists, Auer, according to a report which Zweig despatched three days later to Zionist leaders Moshe Shertok and Chaim Weizmann, inquired whether it would be useful to settle ” large numbers ” of Jews in Ethiopia, and went on to declare that that country was so large and sparsely inhabited that Italy despite her surplus population would rapidly be unable to colonise it effectively. The 250,000 Italian soldiers and workers then in the empire, he said, resembled the Normans at the time of William the Conqueror, in that they possessed nothing but their labour. Jewish initiative and money was therefore needed, and the Jews, if they collaborated with Italy, could be like ” the pike in the carp pond.” He went on to declare that ” Italy would not of course concede a State within a State, but might possibly give far-reaching local autonomy to Jewish settlements.” Besides granting free land the Italians could be expected, he said, to build the necessary road and water installations, and would ” above all take care of the protection of the settlers in a more reliable manner than England in Palestine.” Jewish settlement in Ethiopia, he added, would be politically advantageous for the Jews in that it would make them less dependent on British goodwill in Palestine, and it was in any case useful, he argued, to be on good terms with a rising power such as fascist Italy. Auer therefore proposed that a deputation of two or three Jews should meet the Italian consul in Vienna, who, he claimed, was friendly to him, and able to communicate directly with Mussolini, but it was essential, he declared, that the Zionists should agree in advance not to dispute the validity of the proposed deputation or to disavow the value of Jewish settlement in Ethiopia.

Zweig tells us that he listened to the above arguments without giving them any approval, merely replying that Zionist discipline would not allow any member of their group to participate in the proposed deputation without the approval of their headquarters.

The significance of Auer’s initiative became even more apparent when Berger, an Austrian journalist closely attached to the Italian Embassy in Vienna, shortly afterwards informed Zweig that the Duce was ” prepared to allow 100,000 Jews to go to Abyssinia annually for the next three years,” and Berger added that this offer would ensure that America would keep clear of sanctions, and went on to declare, in almost the same words as Auer, that Mussolini would not permit any ” State within a State,” but was prepared to allow the Jews extensive local autonomy.

Similar proposals seem to have been made to other people in Austria, for Zweig reports that by this time the idea of Jewish settlement in Ethiopia had gained ” widespread currency,” and had been discussed in Vienna’s Jewish circles for several weeks. 5

Shertok and Weizmann, who as Zionists were interested only in Jewish settlement in Palestine, and had in any case no admiration of fascism, appear to have had no desire to co-operate in Mussolini’s plans, and accordingly left Zweig’s suggestions unanswered.

A few weeks later in Cairo, however, a certain Captain Dodona, the director of the Italian telegraph agency in Egypt, approached one of the staff of the Egyptian telegraph agency, Agence d’Orient, who had contacts among the Jewish community in Egypt. The latter subsequently reported to Shertok, on June 10, in terms reminiscent of Auer’s, that the Italians, contemplating ” a large Jewish settlement in Abyssinia,” had proposed to settle no less than ” 500,000 Jews in the autonomous area of Gojam,” and that Dodona had accordingly urged that the Jewish community in Egypt should send a delegation to study possibilities on the spot. ” The Italians,” the official of Agence d’Orient declared, ” are interested that the initiative should come expressly from the Jewish community in Egypt, because, if the Egyptian Jews, who know a little of conditions in Abyssinia, agree to this plan, it will receive the support of the Jews in America.” To make the proposal more palatable, the Italian had added that it went without saying that, if the Jews co-operated in this matter, Italy would reconsider its attitude towards Zionist demands for a Jewish national home in Israel.

The official of Agence d’Orient, however, rejected these proposals, stating categorically that ” no Zionist will support the Abyssinian adventure.” He then explained the matter to the Jewish community in Egypt, warning them that the scheme could lead to difficulties ” in all its aspects.” For his own part, he explains that the Italians in putting forward the plan had been motivated by three main objectives:

(1) To compete with Zionism and buy the friendship of the Jewish people.

(2) To find a financial source for vast Italian settlement in Abyssinia, for they hoped that the Jews would pay not only for their own settlement, but also for that of the Italians.

(3) To create new difficulties for England.

Thus presented, the scheme appears to have won no support among the Egyptian Jewry, for he concludes: ” There is no tendency here to accept the Italian offer.” 6

The idea of finding some kind of Jewish national home in Ethiopia, seems therefore to have waned for over a year and a half, but later came again to the fore when it received some publicity in the fascist press, and gained popularity early in 1938 among many European Jews then suffering from fast-mounting persecution in most parts of the continent. Gunter, the United States minister in Romania, reported for example, on January 20th, 1938, that ” aggregations of village Jews in Bessarabia” had petitioned the Italian minister in Bucharest to be allowed to go to Ethiopia. 6 A few weeks later, in February, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ official publication Informazione Diplomatica, made a pretence of rejecting racial anti-Semitism as existing in Nazi Germany, and advocated instead an anti-Semitism based on ” the struggle against Bolshivism,” many of whose leaders were Jews. The journal went on to state, in hesitant though clearly well thought out terms, that ” responsible Roman circles considered that the universal Hebrew problem could be solved only in one way: by creating in one place in the world, but not in Palestine, a Jewish State, a State in the full significance of the term, capable of representing and protecting by normal diplomatic and consular channels all the Jewish masses dispersed throughout the world.”

This declaration led many observers, notably the French newspaper Le Temps, to conclude that the fascists would not be adverse to some kind of Jewish settlement in Italian East Africa. The paper’s Rome correspondent pondered in an apparently fascist inspired article on February 18, whether Italy was not contemplating offering the Jews ” hospitality . . . in a part of its * empire,’ ” and whether the Duce had not thought of ” creating a Jewish state by ceding to Judaism, with full sovereignty, a part of Abyssinia.” In support of this thesis, the Rome correspondent informed his readers that Italian East Africa was as large as Germany, France, Italy and Spain combined, was sparsely populated, but contained innumerable unexploited resources. Palestine, he declared, was on the other hand only a small territory, and one in which the Jews were faced by opposition from their enemies the Arabs, but in Ethiopia there seemed a priori nothing that could hinder Jewish settlement: ” On the high plateau of East Africa, Jewish work, genius and capital could create a new Zion, a focus of hope and future for the Jews who suffered in the world.” Such a scheme, the correspondent argued, would be warmly welcomed in many quarters. The Vatican, which was not anti-Semitic, as it believed all peoples to be the children of God, could, he argued, be expected to give its approval; Hitlerite Germany would see in it a way of solving one of its most delicate problems, inasmuch as German refugees living in Ethiopia would become less hostile to the Nazis. The Arabs would realise that the project would bring to an end their fratricidal conflict with the Zionists and avoid the necessity of partitioning Palestine, so that Mussolini would increase his prestige as the ” protector of Islam,” while the Jews, for the first time since their dispersal, would be in possession of a country full of resources without having to fight with its owners. The creation of a Jewish state in East Africa, the correspondent averred, would be ” the heaviest blow for British policy,” but ” an important material and moral gain for Italy: a material gain in the sense that if a Jewish State took shape in the Italian possessions of the African continent a bond would be spontaneously formed between this new Zion and the Jewish riches of the world – the City and Wall Street – a bond which would benefit all East Africa. A moral gain: if Italy succeeded in achieving such a creation, she would bring to realisation the most profound dream of the race of David: if she helped millions of Israelites to establish a fatherland, she could attract to herself the sympathies of the Jewish people. International anti-fascist Judaism itself would be brought to terms with Mussolini’s policy. The Duce would be not only the protector of Islam but also the protector of Judah. He would have the glory of solving a problem as old as the world, and at the same time of awarding himself the sympathy of a people whose intellectual and material force constituted a great political power in the entire universe.” 7

Such arguments, to the manifest alarm of the Zionists, who were interested exclusively in Jewish settlement in Palestine, aroused considerable interest in diplomatic circles, particularly during the Anglo-Italian conversations which preceded British recognition on April 16, of Mussolini’s ” conquest” of Ethiopia. On March 4, the London Jewish Chronicle drew its readers’ attention to the fact that there were rumours that the idea of a Jewish National Home might ” become entangled ” in the bargainings then going on between Britain and Italy, and that such rumours were strengthened by stories of ” the Duce’s idea for Jewish settlement in Abyssinia.” The paper, which reflected the Zionists’ exclusive interest in the settlement of Palestine, bitterly attacked the Ethiopian scheme, arguing the utter impracticability of any plan for Jewish settlement in East Africa. ” Zionists,” it declared, ” need have no fears . . . Signor Mussolini, who prides himself on his realism, must soon find out, if he does not know already, that any such project can offer but the poorest prospects. Even if a few Jewish refugees could be induced to settle in that land, the amount of wealth that would accrue in consequence to the Abyssinian exchequer would be infinitesimal. The idea that there exist rich Jewries ready to spend fortunes for the support of some such scheme, even with the added lure of Jewish autonomy, is a pure illusion.” Obviously writing with a view to being read by the British Government, the author’s article went on to declare, whether in earnest or not we have no way of telling, that ” Great Britain could never bargain away her pledge to the Jewish people on this ground. If she did, she would enormously enhance the Duce’s prestige as ‘ protector of Islam,’ and damage her own correspondingly. From possessing at best a negative nuisance value, Italian prestige among the Arabs would be raised to an active and ominous reality, and the prepondering weight of influence among the Arab peoples would shift from Great Britain to Italy. Great Britain may be trusted not to commit Imperial suicide in this way.”

In a further article in the same issue, the paper’s diplomatic correspondent likewise urged the need to oppose proposals for Jewish settlement in Ethiopia. “All Zionists,” he declared, ” should be on their guard against certain possibilities which, however remote they may seem, may emerge from the Anglo-Italian conversations. I refer to the curious suggestion recently mooted in the Italian Press, and in Italian official quarters, that Signor Mussolini would gladly offer Jewish emigrants from Central and Eastern Europe a spacious asylum in the former Ethiopian Empire.

One may discern in this subtle move, which may conceivably enlist Polish and even Rumanian support, a two-fold purpose.” Analysing the scheme and its possible implications for Zionism, the article continued: 41 The Duce is evidently anxious, for reasons which are political rather than humanitarian, to curry favour with the Arab world, by providing an alternative to a Jewish or Anglo-Jewish State in Palestine, and to provide himself with also an argument enabling him to urge on the British Government a permanent and drastic limitation on the Jewish influx into Palestine.

” His second and probably major purpose, in which there is assuredly nothing humanitarian, but stark economic realism, is to divert Anglo-Jewish and American-Jewish capital for the development of the Holy Land to that of Abyssinia, for which Italy, in her present financial difficulties, is herself unable to cater on anything approaching an adequate scale.

” However, this latter purpose is too obvious to deceive anybody, except, perhaps, those unfortunate Jews who are growing restive at the provisional narrowing of the gates to Zion.”

Introducing an element of exhortation into his article, the correspondent concluded:

” The future of Zionism cannot be side-tracked and sacrificed for the sake of any such diplomatic device and financial trick. It is inconceivable that the British Government, in its negotiations with Italy, should allow itself to be deceived by proposals of this nature, or seduced from the path of righteousness and honour, having regard to its solemn international pledges to Jewry and to the League.” 8

While the press was thus debating the pros and cons of possible Jewish settlement in Ethiopia, Mussolini seems to have begun to shy away from the scheme, apparently because he wanted the advantages of colonisation to accrue only to aryan Italians. Press discussion on the possibilities of Jewish settlement in Ethiopia led to an official Italian denial later in the month, when a statement by the Minister of Propaganda declared that ” the widely-current reports that Italy was offering the Jews colonisation facilities in Abyssinia” were ” fantastic.” A similar reply was given in response to enquiries from the Polish Embassy in Rome, while the Italian fascist publication Azione Coloniale bluntly stated: “It is naive to believe . . . that Italy would give up the idea of exploring the colonisation possibilities of Somalia and Eritrea in favour of the Jews. For these reasons, such a solution of the world Jewish problem is to be regarded as entirely out of the question.”

This development in fascist thinking was naturally welcomed in Zionist circles. The Italian Jewish publication Israel, commented that the Government’s declaration should be ” received with satisfaction,” for the Jewish people, it declared, ” regard Palestine as their only National Home,” had a ” spiritual yearning” to return there, and for centuries had considered it ” the land of their fathers, the land which, according to the Bible, was promised to their fathers and children.” The London Jewish Chronicle which was of course basically anti-fascist, also rejoiced. On March 11, under the emphatic heading “Abyssinia? Certainly not!” it declared: ” Can it be that the Duce was really flying a kite, just to see how the wind blew? He has been known to indulge in much less amusing forms of recreation. But if he was-and of course we do not definitely say so-then at least he now has the information he wished for. The kite has flopped ingloriously to the ground. The Jews are not prepared to exchange Palestine even for the somewhat exaggerated fascination of Abyssinia. They prefer to put up with the difficulties they have rather than fly to others they know not of.” 9

Mussolini, it is now clear, had not, however, abandoned the idea of the immigration of Jews to Italian East Africa, but seems for a time to have thought in terms of sending them to Somalia, where conditions were notoriously inferior to the rest of Italian East Africa. On August 3, 1938, he told his son-in-law, Count Ciano, that he had a project for ” turning Mijurtania into a concession for international Jewry,” as the country had ” important natural resources, which the Jews could exploit.” Among others, the diarist cites him as saying, there was ” the shark fishery, ‘ which has the great advantage that, to begin with, many Jews would get eaten.’ ” 10

Such projects acquired increased interest in fascist circles in the latter part of the year as a result of Mussolini’s anti-Semitic drive, which was then gaining strength. Ciano reported on September 4 that ” as for the Jewish concentration colony, the Duce talks now not of Migiurtania, but of Jubaland, which offers better conditions for life and work.” 11

The idea of Jewish settlement elsewhere in Italian East Africa was not, however, abandoned. On the following day Cortesi, the New York Times correspondent in Rome, reported that ” a definite plan for hastening the colonisation of Ethiopia by making it an asylum or place of refuge for Italian Jews ” and ” perhaps at a later date also for Jews from other countries ” was ” seen as a practical possibility today.” The report continued: “Authoritative Italian circles admitted that the recently issued decrees expelling foreign Jews from Italy, forbidding them to take up permanent residence in Italy and banning all Jews from Italian schools were purposely so framed as to leave Ethiopia outside their scope.

” It was said that no obstacles would be placed by the Italian authorities in the way of any Jew residing in Italy, whether an Italian citizen or not, who wished to make his home in Ethiopia, and that Jews from other countries might receive leave to settle there under certain limits and safeguards.”

Cortesi stated that it was thought that ” not a few ” Jews who had come to Italy after January 1, 1919, and were due for expulsion within the next six months, would ” avail themselves of the opportunity thus offered,” while ” the movement to explore the possibilities of Ethiopia as a future home is even more marked on the part of Italian Jews . . . Most of those expressing willingness to go are small government employees faced with the likelihood of having to exist for the remainder of their lives on a pension scarcely sufficient to sustain life.

” Many Jews in the liberal professions who foresee bat they will soon be left without any clients,” he added, ” look to East Africa as their only hope of salvation. Even some well-to-do Jews who could continue to live a life of ease in Italy on the proceeds of their investments find that the recently inaugurated anti-Jewish campaign has placed them in a position of such intolerable moral inferiority that they are seriously considering the advisability of migrating to Ethiopia.”

Emphasising the possible advantage which Italy might obtain from such a policy, he concluded : “An influx of Jews . . . might inevitably hasten the process of colonisation not so much because of the numerical strength of the contingent of Jews willing to rough it in the colony as because of the capital they might be induced to pour into the place.

” If an experiment with Jews now residing in Italy is successful, it is conceivable that Ethiopia may be thrown open to Jews from other countries also.” 12

Sir Noel Charles, the Counsellor of the British embassy in Rome, also expressed the view that the fascist racial laws might serve as a prelude to Jewish settlement in Ethiopia. In a letter of September 10, to the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, he observed that ” various indications” suggested that ” it was not by accident” that the Italian decree of September 3, which ” banished foreign Jews and Italian Jews nationalised (sic) since the war from Italy and Libya and the Aegean Islands, made no mention of Ethiopia.” Discussing the question of settlement in some detail he continued:

” Since the introduction of this and other decrees regarding Jews I have heard from several sources that the authorities have been suggesting to Jews who have complained that life in Italy is being made impossible for them, that a solution of their difficulties would appear to offer itself in emigration to Ethiopia. The Times correspondent now tells me that a colleague of bis recently taxed the Ministry of Italian Africa with the intention of sending Jews to Ethiopia and elicited the admission that, while nothing had been definitely decided, it was in fact proposed that an area should be set aside suitable for both agricultural and industrial development to which both Italian Jews and foreign Jews at present in Italy would be permitted to go. The Times correspondent enquired from the press department of the Ministry of Popular Culture whether the Italian Government had any such intention and was informed that the story could neither be confirmed nor denied.

” It may well have occurred to the Italian Government to utilise Jewish capital at present in Italy for the development of Ethiopia and they may at some future date announce that, while Jews both Italian and foreign who wish to leave Italy, Libya and the Aegean Islands, will not be allowed to export their capital with them, facilities will be offered to them to emigrate and transfer their property to Ethiopia. Such a step would enable the Government to expel Jews, both Italian and foreign, from Italy and the Mediterranean possessions and retain their capital within the Empire, without incurring the odium of turning them out into the world destitute and without involving claims by non-Italian Jews to the right to export capital. Since Jews, however desperate their situation may be in Italy, might be little tempted to take advantage of the offer to go to Ethiopia unless they could be assured that after a few years and after having perhaps having sunk all their capital there they would not be expelled from that territory also, it is conceivable that the Italian Government may also offer some kind of guarantee that Jews will be allowed to remain in Ethiopia unmolested, provided they conduct themselves as good citizens.”

Sir Noel concluded by stating that ” an indirect warning” had been ” issued to international Jewry not to conduct a campaign on behalf of their members in Italy if they do not wish to see the latter suffer for it.”

When the above letter reached London one of the Foreign Office officials, G. L. McDermott, sagely commented, ” The future of the Jewish question in Italy must remain a matter of speculation . . . But We may surely expect a certain amount of hesitation, even on the part of Jews liable to expulsion, at the prospect of going to Ethiopia, and an Ethiopia under fascist rule.” Another of his colleagues, A. N. Noble, on reading these words added his own even sharper comment: ” No ‘guarantee’ that the Italian can give will prevent them from expelling the Jews from Ethiopia a few years hence if it seems to him desirable. The Italian is not a man of his word.” 13

Diplomatic discussions as to the possibility of effecting Jewish settlement in Ethiopia does not seem to have been accompanied by any popular interest in the scheme on the part of Italian Jewry, though a week or so later, on September 21, we find a certain Alice Simon, a German Roman Catholic widow of Jewish descent, writing on the settlement question to the German Consulate in Rome. Explaining that her two Catholic sons, who had been studying in Italy since 1933, were unable to continue their schooling on account of the new Italian racial laws, she inquired whether they would be allowed to work in Italian East Africa. 14 Her inquiry, significantly enough, was left unanswered.

The idea of Jewish settlement in the Italian East African empire nevertheless gained enhanced publicity a few weeks later, when, on October 6, the fascist Grand Council passed a resolution with its anti-Semitic theses, urging the desirability of” controlled immigration ” of European Jews to Ethiopia, though, significantly, it added that the practicability of the plan would depend upon the attitude of Jewry towards fascist Italy. 15

The resolution had immediate repercussions. A Dutch humanitarian, Frank Van Gheel-Gildemeester, who had established the Gildemeester Auswanderer Hilfsaktion, an organisation for assistance to emigrants, in Vienna, immediately sent his secretary, Joseph von Galvagni, to Rome to enquire whether German Jews would be allowed entry permits for the empire on the same terms as Italian Jews; but he does not seem to have received any very definite response. 16

The idea of Jewish settlement in Ethiopia nonetheless led to a flurry of activity in diplomatic circles. The Jewish embassy in Rome made inquiries about the project in October, but reported on November 14, that it had learnt from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that, though the decision to allow Jewish immigration had been taken, ” even the beginning of its implementation had not been made,” and that

” some time would probably elapse before guidelines were laid down.” 17

A few days later, on November 19, the British Ambassador in Rome, Lord Perth, reported that the project had been raised with the embassy by Karl Walter, an Englishman who had ” lived much in Italy.” Walter, Perth noted, had ” found in conversation the belief that Signor Mussolini is serious in his intention of finding an outlet for Jews, Italian and others, in Abyssinia, and there seems to be a feeling that he had expected England to take the matter up and discuss possibilities. Some of Mr. Walter’s friends suggest that Signor Mussolini is disappointed that there has been no official British ‘ reaction’ to the proposal that was first printed in the Informazione Diplomatica bulletin of February 16, and ventilated in the report of the Fascist Grand Council meeting of October 6th.” Emphasising that the project had not won. much support in Jewish circles in Italy the ambassador added that ” some Italian Jews apparently think that the offer has been made solely with the idea of securing Jewish capital for the development of Abyssinia and are therefore reluctant to give any support to the proposal!” 18

Perth reverted to the question shortly afterwards, on November 23, when he informed the Foreign Office that his press secretary, Sir W. McClure, had ” heard . . . from a source that seems truthworthy, that the idea of offering an area for Jewish settlement in Abyssinia was not a bluff, or meant to be a trap for Jews. The matter,” the ambassador continued, ” seems to have been seriously discussed, and the suggestion was made that the Jewish Territorial Organisation should be approached with an offer. Ciano is said to have been against the idea-the informant thought because it might not have been welcome to Germany. In any case it was dropped. But McClure is assured that the Grand Council allusion was made in the hope that England would take the matter up, tentatively at least. Mussolini is reported to have said: ” Well, we shall see how England takes the suggestion.” As far as the Italian opposition was concerned his lordship added: ” Some anti-fascists are urging that England should speedily take up the suggestion of the Grand Council. They say this would * call Mussolini’s bluff’ and they are quite angry with us for not doing so.”

The Foreign Office, though reluctant to appear unduly callous towards the plight of the Jews, had no desire to involve itself in the Duce’s Jewish schemes. One of the first reactions to Perth’s letter was that of F. D. W. Brown, a third secretary, who commented: ” Precisely why it should be for this country alone to react to the suggestion of allowing Jews to settle in Ethiopia is not altogether clear. But in view of these persistent rumours in Rome and the necessity of finding somewhere for refugees, there is something to be said for following the suggestion up, perhaps informally, if only to find out if Signor Mussolini is bluffing or not.” A. N. Noble, second secretary, was more forthright. On November 29, he flatly observed, “I do not quite understand what we are supposed to do or accused of having failed to do. So far as I am aware, the Italians have made no definite statement that they are prepared to settle large numbers of foreign Jews in Ethiopia.” Emphasising the improbability of Mussolini’s having any real interest in the Jews he added, ” It seems to me intrinsically unlikely that Italy would start settling foreign Jews in Ethiopia before she had even sent out any considerable number of her own people, when such a policy might get her into difficulties with her Moslem subjects in Ethiopia and elsewhere and when her favour to the Jews might not be very welcome in Berlin.” Writing in much more forthright terms than those employed by his colleague Brown, and arguing against taking up Mussolini’s plan at the Anglo-Italian talks scheduled for 1939, he went on:

” I think we should study Italy’s advances before we start responding to them, the more so because I cannot see there is any guarantee whatever that the Italians would not permit a number of foreign Jews to settle in Ethiopia and develop the land with their capital and then on some flimsy excuse expel the Jews and not permit them to take their money with them. In fact it seems to me impossible that a state that is carrying on an anti-Jewish campaign at home should be a suitable recipient of Jewish refugees in her overseas Empire. What, for instance, would be the relation between Jews and Italians in East Africa? Incidentally, would the Italians really welcome the establishment in East Africa of a large colony of people which has little cause the love Fascism?

” The Italian mind,” Noble concluded, ” works in a peculiar way and I should uot like to say that the Italians were not hoping that we should take an interest in the settlement of Jews in Ethiopia. Any scheme that might help the Jews is clearly worth considering but I think this one should be approached with considerable caution. If a suitable opportunity offers, it might be possible for the Prime Minister to broach the subject during his visit to Rome, but I do not believe it would be wise. It would be far better to leave it to the Italians to make the first move.”

Nobel’s arguments and analysis won pretty general support at the Foreign Office. One of its officials, Edward Ingram, commented on November 31, ” I agree … I think we had better steer clear of the general Jewish problem at Rome,” while another, R. M. Makins, shared this view observing that it would be ” better to leave the plan alone.” Turning to his own personal assessment of the situation he declared that Italian ideas on ” the possibility of settling Jews in Abyssinia ” seemed ” a somewhat transparent effort to obtain Jewish capital for the development of the country,” and added, ” If Italy intends other countries to take the proposals seriously, and if hints are dropped that this is the case, then the reply seems to be that Italy cannot expect the suggestion to be taken up unless (1) the anti-semitic policy is arrested, (2) the proposals are given definite shape, and (3) are put forward with official authority.”

Such arguments won the support of the Foreign Office, whose permanent Under Secretary, Alec Cadogan, repeating most of Noble’s already cited arguments almost word for word, accordingly wrote to Perth, on December 29, that ” before we could go very far with the matter we should have to have some very much more precise information as to the Italian Government’s intentions. 9 ‘

He therefore concluded by declaring: “Any scheme which might help the Jews is clearly worth considering but we do feel that the idea expounded by McClure’s friend must be approached with caution. It might, I suppose be possible for the Prime Minister to approach the subject during his visit to Rome, but we are inclined to think that in all the circumstances it would be better to let the Italians make the first move.” Lord Perth accepted this verdict, briefly replying to Cadogan, on January 4, 1939. ” In the present circumstances I have nothing more to say than that I agree with your conclusions.” 19

The German embassy in Rome meanwhile had some weeks earlier came to a not too dissimilar conclusion, for a dispatch, dated November 29, 1938, reports that further enquiries from the Italian authorities had elucidated that the question of Jewish settlement was ” still in its early stages, and it could not be foreseen when and in what manner the decision would achieve practical realisation.” 20

Steps were, however, taken by the Italian colonial administration at about this time to investigate possibilities of Jewish settlement in Ethiopia In November, 1938, the then Viceroy, the Duke of Aosta, called one of his men, Colonel Giuseppe Adami, and, as the latter notes in his diary, ” after having announced that he would be entrusted with a most interesting and important task,” instructed him to find a suitable zone capable of accommodating 1,400 Jewish heads of families, which number, he was told, might soon be doubled, and subsequently further increased. ” The zone,” Adami’s diary explains, ” had to be the best from the point of view of health: no malaria, no tsetse fly, etc; having a temperate climate, abundant water resources, land capable of very good agriculture-industrial exploitation, not on the principal transport route and inhabited by a peaceful population, preferably pagan where there were a minimum of Coptic churches and mosques, so as to avoid discord of a religious character.”

The Viceroy informed Adami that the survey had been requested by Mussolini as a result of an agreement with the British Government, that the proposed settlers would be refugees expelled by Nazism from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia, and that it was preferable that they colonise Italian East Africa than Palestine where they would create difficulties with the Arab population. The Duke then dismissed Adami with a smile, saying that he was awaiting the latter’s report that he had discovered a small ” earthly Paradise.”

Two days later Adami drove south to Borana where he selected an area at Aresox, a 100 kilometres from the Kenya frontier, which seemed to him suitable in view of its relationship to routes of communication, the frontier and to the main urban centres as well as for its climate, soil, and ” above all human setting.” The area was about 8,000 square kilometres in extent, or almost half the size of Palestine and was around 1,200 metres above sea level, watered by the Dawa-Parma river, and apparently suitable for the raising of cattle, and the consequent development of milk, butter and other cattle products, as well as for the cultivation of cotton, castor oil and tobacco, and for the exploitation of forestry resources. Adami handed his report to the Duke of Aosta on December 5, 1938, who at once despatched it to the Duce. 21

The idea of settling European Jews in Ethiopia was meanwhile widely discussed, thought it is significant that it had little or no appeal among Italian Jews far less in Zionist circles. The December issue of the New York Jewish Workers’ Voice carried a sarcastic article by S. Ethelson, entitled ” It is Good to be an Orphan,” in which the author declared:

” Powerful nations, enjoying sovereignty and freedom, have only their own countries to fall back upon. But Jewish refugees have a choice of many lands to pick from. If one prefers the humid heat of the jungles of Guiana, he is welcome to it. If someone else’s taste runs to tsetse flies and similar blessings of East Africa, they are at his disposal. Verily, it is good to be a refugee.” 22

One of the chief protagonists of the scheme for settling Jewish refugees in Ethiopia at this time was, interestingly enough, President F. D. Roosevelt of the United States who, desirous of deflecting Jewish immigration away from the States, wished, according to his Jewish aide Bernard Baruch, to establish a ” sanctuary in Africa, financed by private funds and open to all refugees,” and on one occasion ” sketched a map of Africa on a scratch pad, outlining the temperate, largely unpopulated areas where such a scheme might be put into effect.” 23 . Roosevelt on December 7,

1938, accordingly wrote a flattering not to say sycophantic letter to the Duce in which he referred to the latter’s much publicised role as ” peace-maker ” at the Munich conference of September 29, of that year, and declared that this had been ” recognised everywhere as an historic service to the cause of peace.” The President then proceeded to draw the fascist dictator’s attention to ” the problem of finding new homes for the masses of individuals of many faiths who are no longer permitted to reside freely in their native lands,” and enclosed a memorandum giving his approval to the idea of Jewish settlement in southern Ethiopia and the northern part of the British colony of Kenya. 24 This remarkable document declared:

” In searching the areas which would appear to lend themselves to resettlement, President Roosevelt has been particularly struck with the appropriateness of the Plateau, a small part of which lies in the southwestern section of Ethiopia, and the greater portion in areas lying to the south of Ethiopia. It has occurred to him that the Chief of the Italian Government may believe that adequately financed colonisation of refugee families in this area would be in accord with plans which the Italian Government may have formulated for the development and economic reconstruction of Ethiopia.

” If the Chief of the Government should see merit in this plan, and should care to make it his own and urge other states holding sections of this Plateau to do likewise, the President of the United States would be prepared to give the proposal as part of a general plan his public support.” 25

Roosevelt’s letter and the accompanying memorandum were delivered to the fascist dictator on January 3, 1939, by the American ambassador, William Phillips,

who records that he proceeded to read out the latter document slowly. When he had concluded the part dealing with proposed Jewish emigration to the plateau of Ethiopia and Kenya the Duce, he says, ” interrupted by saying that this suggestion was impracticable-that this particular region in Ethiopia was inhabited by a people who were wholly unsympathetic to the Jews, and that he had already offered a far better region to the northeast of Addis Ababa, a proposal to which, however, the Jews themselves had not received favourably. Thereupon, he opened a map of Ethiopia, examined the suggested Plateau region, and showed me somewhat vaguely the area which he had already suggested for Jewish colonisation.” 26

The conversation then acquired a general character, Mussolini going on to speak of the Jews at length. Philips observes that he was ” impressed” by the dictator’s ” apparently genuine antagonism ” to them, though he notes that the Duce ” expressed the opinion that the Jews should have a state of their own which need not be necessarily a large or important one but at least a territory where there could be a Jewish capital and government … He admitted that it would be difficult to find a suitable place on the globe for a bona fide Jewish state but he seemed convinced that was the only answer to the problem.

” I found it necessary,” the ambassador concludes, ” to bring him back several times to the original inquiry as to whether he would join with other leaders and states in trying to find a solution. Finally he agreed to do so.” 27

Ciano confirms this account, declaring that the American ambassador brought ” some suggestions regarding the settlement of the Jews, for whom President has thought of a part of Ethiopia and the surrounding colonies,” but that ” the Duce rejected this proposal, and said that only Russia, the United States and Brazil have the material possibilities for solving the Jewish question.” 28

News of the above talks gained rapid currency and the following day, January 4, 1939, an Italian Jew, Dr. E. T. Cohen, of the Comitato Asistanza Profughii Ebrei, called on the British embassy in Rome to warn the British Government of what he expected would be Mussolini’s next move. He stated, as Lord Perth subsequently reported, ” that Jewish circles in Rome had obtained certain information which might sound fantastic but which nevertheless they believed to be correct. There was,” he had argued, ” reason to believe that if the Jewish question came up for discussion between the Prime Minister and Mussolini and if Mr. Chamberlain asked for some mitigation in the lot of the Jews in Italy, Mussolini proposed to inform Mr. Chamberlain that he was willing to arrange for all Italian Jews (it was gathered that Dr. Cohen thought this might also apply to foreign Jews) to be settled in Ethiopia in the neighbourhood of Lake Tana where, Dr. Cohen said, there is already a community of some 50,000 Jews who have been there for some 2,000 years (though they have turned nearly black in the interval). Mussolini, according to Dr. Cohen, would represent this as a favourable solution of the problem which was being made as a concession to the known interest of the British public in the fate of the Italian Jews. He added that the information of the Jews in Italy was that reasonably generous provision would be made for the emigrants and that there was good land for settlement round about Lake Tana. In return for this concession Mussolini would ask for facilities for the building of a road linking Italian East Africa with Libya.”

Cohen’s intervention evoked but limited interest on the part of the ambassador who went on to note that he did ” not . . . believe that this story, which Dr. Cohen rightly called fantastic, can correspond to the actual intentions of the Italian Government,” the more so as ” the object of Dr. Cohen in relating it was obviously to suggest that His Majesty’s Government might be prepared to find some other solution to the problem of the Italian Jews.” Brown of the Foreign Office nevertheless commented that Cohen’s story was ” of some interest,” especially the part to the effect that ” Signor Mussolini would regard a Libya-Ethiopia road as a quid pro quo for the settlement of the Jews in Ethiopia.” His colleague Noble, on the other hand, was more sceptical and commented, ” I don’t think this is very important. We have heard the refuge in Ethiopia story before and I still view it with suspicion.” 29

Cohen, who was by no means discouraged by his reception at the embassy, then made his way to London, where he called on the Foreign Office on January 9, to say, as an official report states, ” that Jewish circles in Rome were growing apprehensive in regard to what might be discussed between Mr. Chamberlain and Signor Mussolini. They feared lest support might be given to the idea of settling the Jews of Italy in Ethiopia-the Jews would find it intolerable to settle in any territory under Italian domination.

” He added that the communication recently made by the United States Ambassador to Signor Mussolini had created a bad impression in Jewish circles, since it was understood that Mr. Phillips had discussed the idea of settlement in Ethiopia.” 30

In Rome meanwhile the fascist authorities proceeded to give the settlement scheme some publicity and several not unfavourable reports found their way into the press. The Rome correspondent of the Evening Standard for example reported on January 9, that since Italy ” cannot hope to develop Abyssinia as she would like for many years ” she ” would like someone to share the pioneer work with her and she can see no one who would be likely to be more ready to assist than the Jews.” 31 Le Temps of January 13, on the other hand, quoted its Rome correspondent as stating, with truth, that Phillips’ interview with Mussolini had not followed its anticipated source, for, the correspondent surmised, the Duce apparently feared that ” Jewish immigration in Ethiopia might entail certain dangers for the future of the empire.” 32

The fascist dictator nevertheless seems to have found the plan intriguing in that it enabled him to continue posing as a world statesman and arbiter of events as he had done a few months earlier at Munich. On meeting Chamberlain on January 11, the Duce, according to the British record of the event, *’ said that Jewish refugee problem was not a local one, but one of general application. It was already not a problem in Germany only and he thought probably it would be bound to arise in many other countries, including the United Kingdom. At this point he broke into a broad smile and said that was his opinion.

” The best permanent solution,” the report quotes him as continuing, ” would be the establishment of an independent sovereign Jewish state, which would not require that all Jews should live in it, since, as subjects of such a state, they would have their status and their official representation in whatever country they lived, like other people.” So far from broaching the question of Jewish settlement in Ethiopia the dictator spoke in only the most general of terms. ” To find a place for such a state,” he declared, ” one must look to the countries that had large areas of territory such as the United States of America, Soviet Russia or Brazil. He said, with some indication of irony, that it might be some time before such a solution was practicable, but it must be regarded as a long-term aim.” 33

Ciano in his account of the conversation states that his father-in-law told Chamberlain of the message he had received from Roosevelt, and went on to pontificate that the Germans, wishing ” to solve the Jewish problem in a totalitarian manner,” could be expected ” to make some sacrifice in order to further the total exodus of the Jewish masses from German territory,” though he added significantly, ” One must not demand too heavy sacrifices from the German people, which has suffered greatly because of the Jews.” 34

Such discussions, however, did not reckon with the Jews of Italy who, particularly after the enactment of Mussolini’s racial laws, seem to have had no desire to assist the fascist development of the empire. Representatives of the Committee for the Assistance of Jews in Italy accordingly called on the American embassy in Rome on January 11, as Philips notes, when ” their spokesman stated that if it were true that the President’s message to Mussolini contained a suggestion for settlement of Jewish refugees in Ethiopia his Committee desired to impress upon the American Government that not a single Jew would voluntarily place himself at the mercy of the Italian regime in Ethiopia or anywhere else.” The ambassador also reported that the Jewish organisation had likewise frankly informed the British Prime Minister, that ” they could not agree to any plan for the settlement of Jews in Italian territory.” 35

This dramatic, and in the circumstances of fascist oppression, somewhat daring action by the Italian Jews seems to have wrecked the possibility of an accord between Italy and America. On January 11, Mussolini wrote to Roosevelt, replying to the latter’s letter and memorandum, but observing: “In so far as Ethiopia is concerned it is not possible to consider the organisation of Jewish emigration in that legion. Apart from every other consideration, the general attitude of Jewish circles towards Italy is not such as to make it advisable for the Italian Government to receive on any of its territory large numbers of Jewish immigrants.” 36

The critical situation of the Jews was, however, such that the Gildemeester organisation decided to persevere in its efforts. On May 25, 1939, the good Gildemeester, who, remarkably enough ended his letter with the ritual formula ” Heil Hitler,” wrote from Vienna to the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin claiming that the Italian Ministry of the Colonies had agreed that ” non-Aryan Christians” would be allowed to emigrate to Abyssinia, and that a commission of four or five persons would be permitted to visit the country to inspect a piece of land 200 kilometres south of Addis Ababa to ascertain whether it was suitable for colonisation purposes. 37

The prospect of large numbers of Jews migrating to the Italian empire – which could have been a lucrative business – also interested a German travel bureau, the Hanseatischen Reiseburo, or Hanseatic travel bureau, an organisation with branches in Vienna and Berlin, whose director Heinrich Schlie visited Rome in June in an attempt to acquire the monopoly of the business. 38 Introduced to the Italian authorities by the German embassy he met Commander Denti, an official of the Ministry of the Colonies, and Dr. Rodriguez, an employee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, both of whom categorically informed him that no permission for settlement had ever been given to Gildemeester, though Rodriguez referring to Gildemeester’s proposed commission of investigation, remarked that anyone could on request be allowed to go to Abyssinia ” but on]y as a tourist.” Schlie, who was emphatic about his desire for a monopoly of the Jewish travel to the empire, promised that, if granted it, he would make a careful selection of immigrants, and would give permits only to those who would be desirable from the ” moral point of view ” and were possessed of the professional qualifications needed for settlement. 39 Later, on July 22, he drew up a memorandum for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in which he argued that Ethiopia could absorb large numbers of Jewish immigrants more conveniently than Libya, and that the Jew could be useful for the development of the empire because he had great ability to adjust to his environment and had many useful skills, though care, Schlie reiterated, would be required to ensure that each immigrant devoted his attention exclusively in the direction desired by the Ministry. He therefore recommended that the Jews be settled in uncultivated lands away from towns, and that they come mainly as farmers but also to a certain extent as craftsmen who, he averred, would also be needed in the settlement process. A flood of Jewish traders, he emphasised, was not desired, and each immigrant registering at his office would, he promised, bind himself to work exclusively for at least 15 years in the profession agreed upon; persons failing in this obligation would have their office permit withdrawn. Offering the Ministry his full co-operation he promised that he would select the ” human material ” with care, and, declaring that he enjoyed the confidence of the German authorities, he affirmed that he would act at all times in the interests of Italo-German friendship. 40

Gildemeester meanwhile continued to assert that the Italians had agreed to permit *’ non-Aryan Christians” to emigrate to the empire, though the German embassy in Rome reported on August 4 5 that no plans had yet been formulated and that the Italian Government was not likely to approve of any such scheme ” unless it could assume at least tacit German agreement.” 41

Gildemeester, however, was not dissuaded by the difficulties, and succeeded in gaining considerable publicity for his scheme. The New York Times announced on August 13, that ” the prospects of sending thousands of Jewish refugees to settlement projects in Ethiopia brightened tonight as a result of Italian encouragement,” 42 while the Jewish Telegraph Agency News of August 15, reported that German and Italian officials were negotiating with the Gildemeester organisation. It was announced that a five-man commission led by Gildemeester’s assistant, Hermann Fuernberg was to visit Geneva, Rome and Addis Ababa, and, according to the New York Times, that ” the establishment of an agricultural community of at least 20,000 families in the Ethiopian region of Lake Tana ” was contemplated. The Times of August 14, likewise reported that Gildemeester action, which it described as a Dutch organisation assisting Jewish refugees, hoped ” to establish a large number of agricultural settlements,” and added: “The land made available is rich, and transport facilities are continually improving. Mr. Gildemeester, a wealthy Dutch philanthropist, has always considered the settling of Jews in agricultural communities on sparsely settled lands as the best possible solution of the Jewish problem.” It was planned, according to the Havas agency, that the commission would remain in Ethiopia until the end of September ” visiting several locations which have been picked as possible sites for model villages to be constructed by refugees.

” Prospective emigrants have expressed a willingness to go to Ethiopia on condition that they be permitted to settle in the fertile highlands bordering Lake Tana. The Italian Government has offered them land some distance south of the Lake, however, and the forthcoming conversations at Rome are expected to deal with this point.

“A staff of engineers and technicians employed by the Gildemeester organisation have worked out complete details of five model villages, accommodating about 14,000 emigrants. It is hoped to have work on these villages started by next June. The plans for the villages include a central plaza with a synagogue on one side and a Catholic church on the other. It was explained that the church will be for the many Jews who have been converted in the past few years.

” It has been estimated that Ethiopia can accommodate about 5,000,000 more people. In the Lake Tana region alone a vast territory of about 50,000 square miles virtually is uninhabited. The land is believed suitable for growing wheat, coffee and numerous tropical fruits and grains.” 43

Such enthusiastic reports, which received extensive coverage in the world press, seem, however, to have been mainly based on wishful thinking, and were officially denied in a secret directive by the German news agency Deutschen Nachrichtenburos on August 21. 44

Though discussion continued for some months more the outbreak of the European war a fortnight later on September 3, spelt the effective end of the plan. The Chief of the German Security Police wrote to the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on October 30, telling them that the Gildemeester organisation and the Hanseatic travel bureau had both been advised temporarily to suspend their efforts with regards to the emigration of Jews to Abyssinia and asked them to inform him if on the Italian side any definite ideas were formulated. 45

Gildemeester’s Jewish aide Fuernberg, perhaps the last remaining enthusiast for the scheme, now transferred his headquarters from Vienna to Rome. 46 There he issued a prospectus, boldly adorned with the Cross of Christ and the Star of David, which was written in German, Italian and English. In this document he declared that his organisation, which, he claimed, had already assisted in the emigration of 30,000 persons from Germany, was ” of the opinion that the simple work of facilitating their leaving is not sufficient, but that on the contrary it is necessary to provide the emigrants with the prospect of a fixed home and above all of profitable work. We were, and are also now, of the opinion,” he added, ” that this will be possible only when an attempt at colonisation on large scale can be tried with non-aryans who are suitable for this work and who have the necessary goodwill.”

The report went on to state that the Gildemeeste Committee, ” after a careful survey of all territories suitable for this project, addressed itself to the Italian Government in order to obtain a concession of land in Abyssinia,” and that Italian Government had ” given its agreement to a preliminary investigation,” at which stage, however, the war had broken out. Undeterred by this event Fuernberg declared that the commission would continue with its ” previously agreed researches ” and would prepare a report, for ” the Gildemeester Organisation,” he declared, ” believes that during the war plan for peace must be prepared.”

Developing this thesis the memorandum observed: ” Since we are firmly convinced that regardless of the issue of the war a great number of Jews will be compelled to leave their countries or will be willing to emigrate, we decided to carry out that duty which we had imposed on ourselves: the preparation of a great Jewish colony. The Jewish problem calls for a solution and certainly during the next peace talks will find a solution of one kind or another. We are still of the convinced opinion that a complete programme for the solution of the Jewish problem ought to be presented to the peace conference which, sooner or later, will take place. We are still convinced that a solution satisfactory to all parties can be found only if the Jews are permitted to participate in the preparations and decisions of the Conference. It is a matter of making Judaism active rather than passive.”

This insistent memorandum concluded by asserting that action was ” an absolute necessity in view of the wandering and starving refugees throughout the world and in consideration of the non-aryans destined to death by starvation in Germany.” 47

The latter statement by ” the Jew Fuernberg,” which was promptly reported to the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on November 25, by its embassy in Rome, 48 incensed the Nazis who complained that the Gildemeester organisation was resorting to anti-German propaganda. The result was that the organisation was formally annulled by a German police order of January 1, 1940, and Fuernberg at about the same time made good his escape to Barcelona in Spain. 49

From Spain the indefatigable Jew made his way to New York where he continued his advocacy of Jewish settlement in Ethiopia well after the re-establishment of Ethiopian independence in the Spring of 1941. In a remarkable, and somewhat historically naive document drawn up in May, 1942, he drew attention to the extermination of Jews in Hitler’s Europe, and urged the need after the war to settle the survivors outside Europe. He nevertheless rejected the idea of Zionism on the grounds that ” Palestine was by no means able to absorb all the Jews compelled to leave their home-lands,” and that the Zionist arguments that ” Palestine is as large as the Jews make it ” did not ” increase the size of Palestine nor do they diminish other people’s resistance to a Jewish state in Palestine.” Arguing that ” the future of mass immigration in Palestine ” was ” not at all a bright one” he declared that his proposal was ” to offer the Jews driven out of Europe the possibility of building up a new home elsewhere,” and that the ” founding of a self-governing independent state for the Jews of Europe may be one step towards the solution of the so-called ‘ Jewish problem.’ ” He therefore urged the Jews to renounce any exclusive interest in Palestine, agreeing to share it instead with Christians and Moslems as ” the Holy Land of all Mankind,” and to ” create a Jewish state outside Palestine.” What was important, Fuernberg declared, was that the territory selected:

“… should be sufficiently large to avoid fresh difficulties for one or two generations hence.

” It should be thinly populated so that an accommodation with the existing inhabitants can be easily reached.

” It should have a useful climate and it should hold out good prospects for economic development.”

Various territories, he explained, had been proposed, among them ” Uganda, Kenya, Angola and Northern Kimberley,” but his own proposal was ” to unite the so-called HARRAR-territory of Ethiopia with part of British – Somaliland and create there a state for the European Jews.” This territory, he argued, “is large enough; it would be easy to devote 60,000 to 70,000 square miles there for this purpose. The territory is inhabited by a small agricultural population, and are not likely to raise great difficulties. Nevertheless it will be necessary to remember the lessons learned by the Palestine experience, namely, to prevent the territory being overrun by people from other parts of Ethiopia and to keep out foreign agitators.”

” The climate on the plateau,” he added, ” is absolutely healthy and suitable for Europeans. Those parts of the Somali coast which have a bad climate could be improved in measurable time by irrigation.

” The HARRAR territory is particularly suitable for agriculture and hence for mass immigration. It would have ready markets for its agricultural and later its industrial products in the interior of Africa, in the Arabian countries and in parts of India.”

Turning to the political aspects of his proposal Fuernberg noted that the area proposed for settlement belonged partly to Great Britain and partly to the Empire of Ethiopia. The British, he declared, had proposed to cede part of British Somaliland to Ethiopia in 1935 in an attempt to achieve a settlement with Italy and it was ” therefore not impossible that the British Government may be ready to cede a rather larger portion of Somaliland together with the port of Berbera to the European Jewish state we have in mind.” As for Ethiopia, he concluded:

” The Imperial House of Ethiopia claims its descent from the Jewish King David, and the Emperor bears the title * Lion of Judah.’

” Should this not also imply a certain obligation to offer much needed help to his half-brethren in Europe and to receive them on terms worthy of the 20th century ?

” The Jews on their part should have no objection to recognising the over lordship of the Emperor with some guarantees from Great Britain and U.S.A.

” May the Lion of Judah prove that he combines the courage of David, the wisdom of Solomon, and the good sense of the Queen of Sheba.” 50

The World Jewish Congress duly denounced the Fuernberg scheme as a ” rat trap,” but this did not prevent one Jewish refugee in the States, Erwin Kraft, from establishing an organisation with the imposing title of the ” Harrar Council for the Autonomous Jewish Province in Harrar.” 58

A year after the liberation of Ethiopia, though still seven before the establishment of the Jewish State of Israel, such ideas, born originally of Mussolini’s invasion of Africa’s last independent empire, were of curse illusory . . .

The self-styled ” Harrar Council for an Autonomous Jewish Province in Harrar” was, however, slow to realise this fact, for it continued to urge its ideas on both the American State Department, and apparently, the Ethiopian Government. As late as December 18, 1943, we find the ever-hopeful Kraft accordingly writing to Howard K. Travers of the State Department to declare:

” When I had the privilege of being received by you last week, I told you we were going to present our statement to the Minister for Ethiopia for transmission to his Government, and that we would let you have a copy. 14 We now feel that this statement should be rather more comprehensive than was originally intended. A lawyer of international experience who has already carried on negotiations with the Emperor of Ethiopia has become interested in our plan and is assisting us in the formulation of the statement. It will therefore take a little longer than was at first anticipated, but 1 hope to send you a copy in the near future.” 52 It is on this hopeful note of Kraft’s that the documentation on the scheme peters out, its protagonists having in all probability at last come to realise the futility of their efforts . . .

REFERENCES

1 E. Momigliano, Storia tragica e qrotesca del raztismo fasista (Milano. 1966) passim, R. De Felice, Storia degli ebrei italiani sotto il fascismo (Roma, 1962), passim; See also R. Pankhurst, “Fascist Racial Policies in Ethiopia 1922-1941,” Ethiopia Observer (1969), XII, No. 4, pp. 270-86.

2 Na nostra bandiera, April 15, 1936; Israel, May 7 and 14, 1936. See also De Felice, op. cit., p. 226.

3 Great Britain, F.O., 371/20158/131-42; Daily Telegraph, June 30, 1936; C. Roth, The History of the Jews in Italy (Philadelphia, 1946), p. 516; ” Ethiopia,” The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, IV, 185.

4 De Felice, op. cit., p. 226.

5 Jerusalem, Central Zionist Archives, 525/9829.

6 U.S.A., Department of State, Foreign Relation of the United States, Diplomatic Papers, 1938 (Washington, 1955) II, 677.

7 Le Temps, February 19, 1938.

8 Jewish Chronicle, March 4, 1938.

9 Idem, March 11, 1938.

10 Ciano, Ciano’s Diary, 1937-1938, (London, 1952), pp. 148-9.

11 Ibid, p. 151.

12 New York Times, September 6, 1938. See also Il progresso italo-americano, September 7, 1938.

13 F.O., 371/22442/7593.

14 Germany, Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives, 83/50, Simon, September 21,1938.

15 U.S.A., State Department, Foreign Relations of the United States, op. cit., II, 594.

16 Germany, Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives, German Embassy in Rome, 83/50, December 13, 1938.

17 Idem, 83/50, November 14, 1938.

18 F.O., 371/22443/9300.

19 F.O., 371/22443/9454.

20 Germany, 83/50, November 29, 1938.

21 Il Gazzettino del Lunedi, May 11, 1970; Israel, June 4, 1970.

22 D. S. Wyman, Paper Walls. America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938-1941 (Amhurst, 1968), p. 58. See also p 239.

23 B. M. Baruch, Baruch. The Public Years New York, 1960), p. 274.

24 U.S.A., State Department, Foreign Relations of the United States, op. cit., I, 858.

25 Ibid, I, 859-60.

26 Ibid, 1939, II, 58.

27 Ibid, II, 59. See also Wyman, op. cit., pp. 58, 239; H. L. Feingold, The Politics of Rescue. The Roosevelt Administration and the Holocaust 1938-1945 (New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1970), p. 104; De Felice, op. cit. p. 392.

28 G. Ciano, The Ciano Diaries 1939-1943 (London, 1946), p. 5.

29 F.O., 371/23799/176.

30 F.O., 371/24080/896.

31 Evening Standard, January 1, 1939.

32 Le Temps, January 13, 1939.

33 E. L. Woodward, R. Butler and M. Lambert, Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939, Third Series III, 1938-9, p. 519. See also F.O., 371/23783/339-40.

34 G. Ciano, Ciano’s Diplomatic Papers (London, 1948), p. 261. See also De Felice, op. cit., p. 261.

35 U.S.A., State Department, Foreign Relations of the United States, op. cit., 1939, 11,64-5.

36 Ibid, II, 63.

37 Germany, Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives, 83/50, May 25, 1939.

38 Ibid, 83/50 German Embassy, June 22, 1939.

39 Ibid, 83/50 German Embassy, June 30, 1939, Schlie, July 22, 1939.

40 Ibid, 83/50, Schlie, July 22, 1939.

41 Ibid, 83/50, German Embassy, August 4, 1939.

42 New York Times, August 13 and 15, 1939.

43 Jewish Telegraph Agency News, August 15, 1939; The Times, August 14, 1939.

44 Germany, Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives, 83/50, Doutschen Nachrichtenbiiros, October 21, 1939.

45 Ibid, 83/50 Chief of Security Police, November 2, 1939.

46 Ibid, 83/50, German Embassy, November 25, 1939.

47 Ibid, 83/50, Gildemeester, November, 1939.

48 Ibid, 83/50, Germany Embassy, November 25, 1939.

49 Ibid, 83/50, Chief of Security Police, January 1, 1940.

50 H. Fuernberg, The Case of European Jews (New York, 1943), passim.

51 Feingold, op. cit., pp. 108, 325.

52 U.S. State Department, correspondence, 1943, 840-48, refugees, 4967.