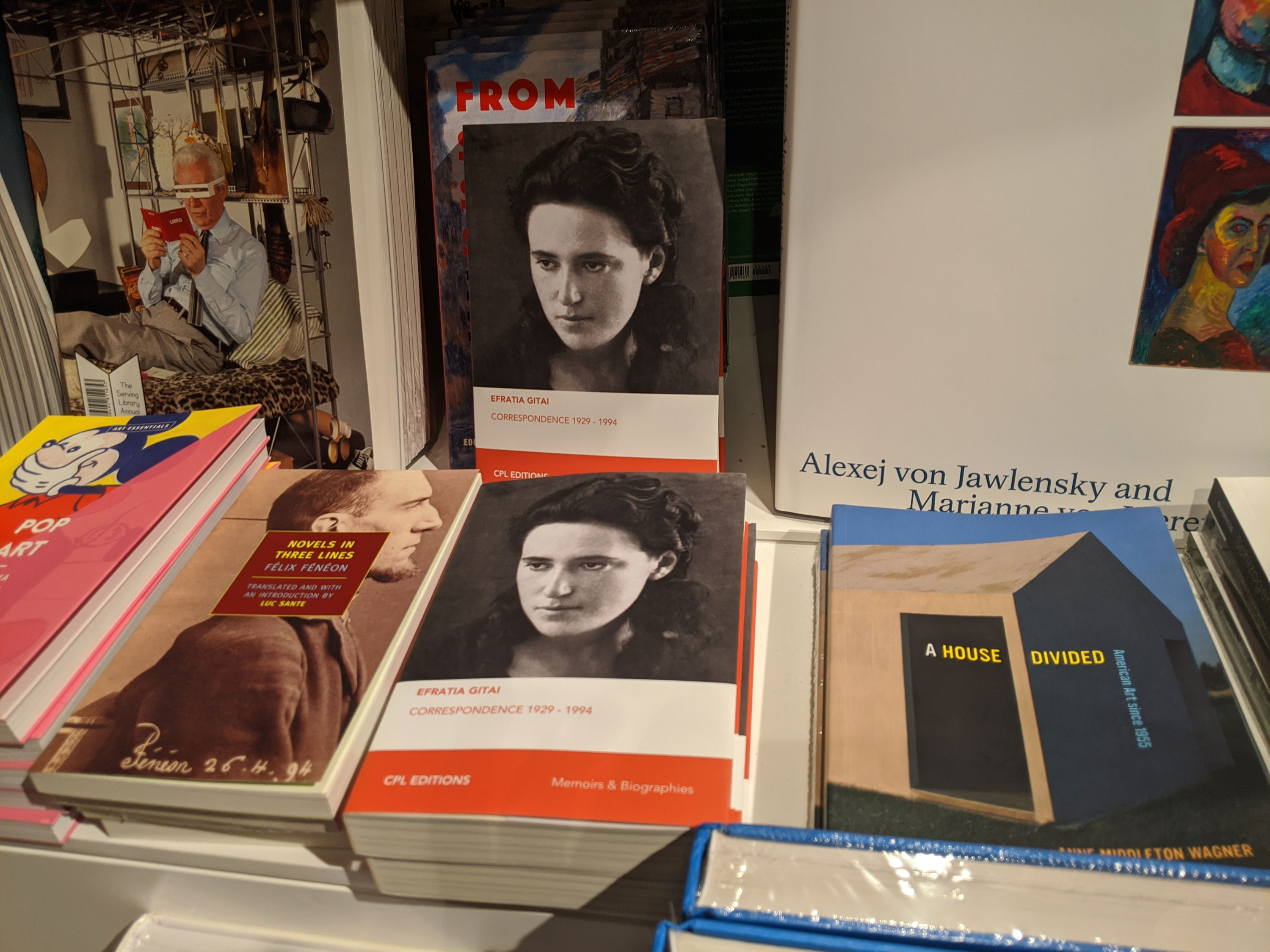

Amos Gitai once told me: “When the credits scroll down at the end of a screening, a new film begins in the mind of the spectator.”With this image in mind, I set to write down some powerful impressions after viewing the four films presented at MoMA (March 5-8) in connection with the publication of Efratia Gitai Correspondence 1929-1994 by CPL Editions.

From personal anecdotes, open-ended questions, and reflections that Gitai poses in his films and post-screening remarks, two concepts linger powerfully on: cinema as archive (historical and personal) and cinema as a civic gesture.

I do not think it is a stretch to say that by attempting to create works of art that serve both as an archive of memory, and as a civic gesture, Gitai’s motivations echo those of Primo Levi’s.

The memory Gitai is trying to archive is that of the foundation and striving of a young country: contradictions, aspirations, violence, opportunities, beauty, and all. He wants to preserve the competing narratives that constitute the history of Israel. He pursues them through a clear-eyed and dispassionate exploration of the juxtapositions of present and past, and through the narrative prism of Jewish history and literature. With a gaze that is more frequent among historians than filmmakers, he captures history, not as a static reality, but as a sequence of events, layers, and points of view.His first feature film, Esther, from1986, recounts the story of biblical Queen Esther, through a series of tableaux vivant. We are in ancient Persia, yet the sound of traffic and sirens, and the landscape of the former Arab quarter of Haifa makes us aware that this is a retelling of the story in and for a contemporary world. The very specific here and now intersects with the biblical text until, in the final section, each actor, steps out of character to reveal bits of his or her biography.

The memory of the Book of Ester, in particular the emphasis on human agency in the historical process, emerges in the film as a parallel plane to the memory of the languages, landscapes, tension of Jewish and Arab Haifa at the end of the 1980s.

Amos Gitai was born in 1950, only two years following the creation of the State of Israel. The history of his young country and his personal history unfold simultaneously and constitute the substratum of these films.

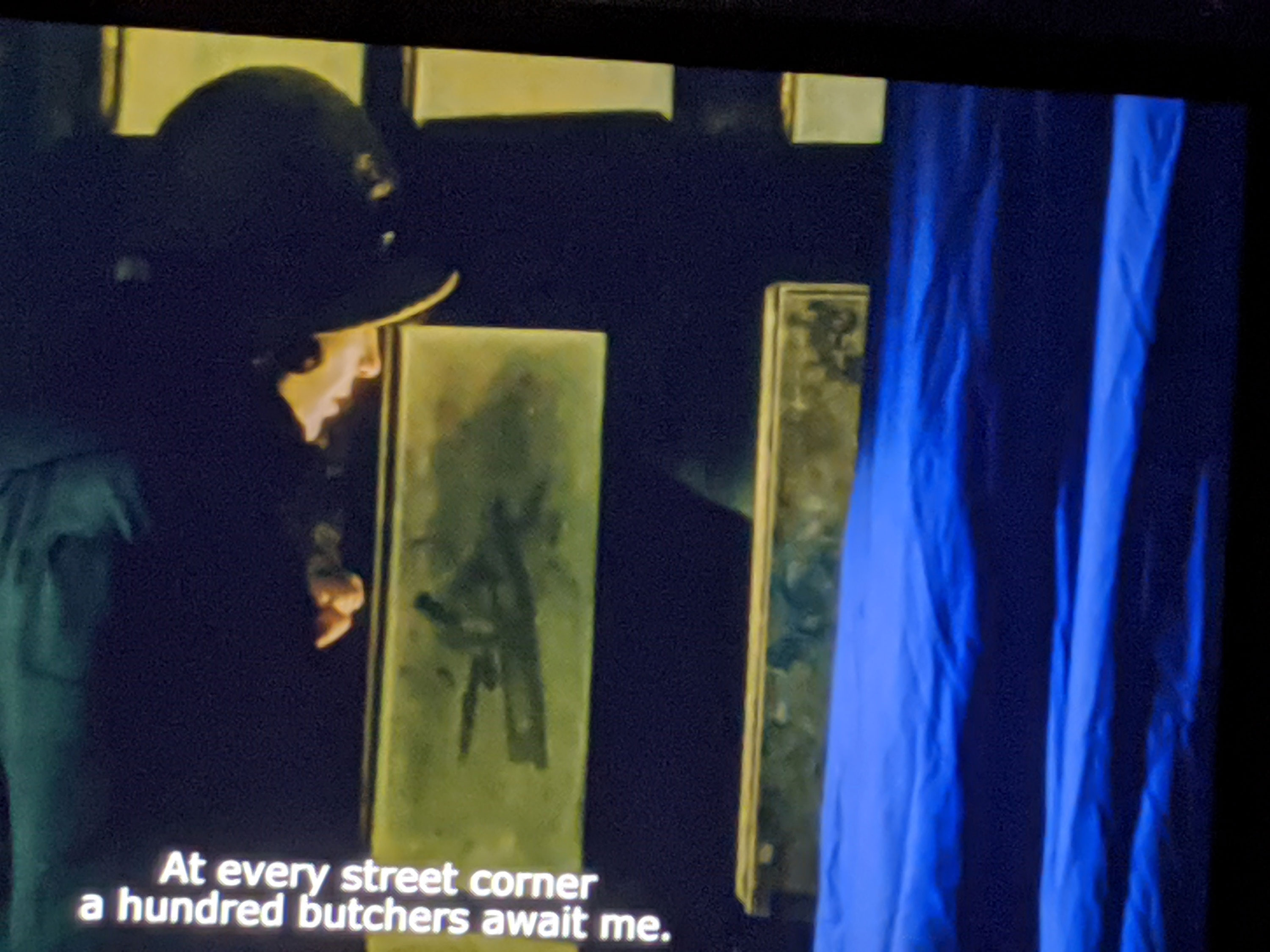

His mother, Efratia, born in Palestine, was part of a socialist, intellectual, and artistic group among Israel’s founders. His maternal grandparents had left Russia for Palestine after the failed socialist revolution of 1905 — emigration for ideological motives. His father, Munio Weinraub Gitai, who had been an architecture student in Dessau, Germany, moved to Palestine after the Nazis closed the Bauhaus in 1933 — emigration by necessity and racial discrimination. The two stories are echoed in the two women protagonist of his second feature, Berlin- Jerusalem from 1989. Loosely based on the lives of the expressionist poet Else Lasker- Schüler and the Russian Zionist Mania Shohat, the film tells the story of women who driven by ideological fervor or persecution, choose to build a new life in Palestine. Juxtaposing Berlin and Jerusalem — even stylistically — the film contrasts the past with the uncertainties and hopes of the future. History in the making.

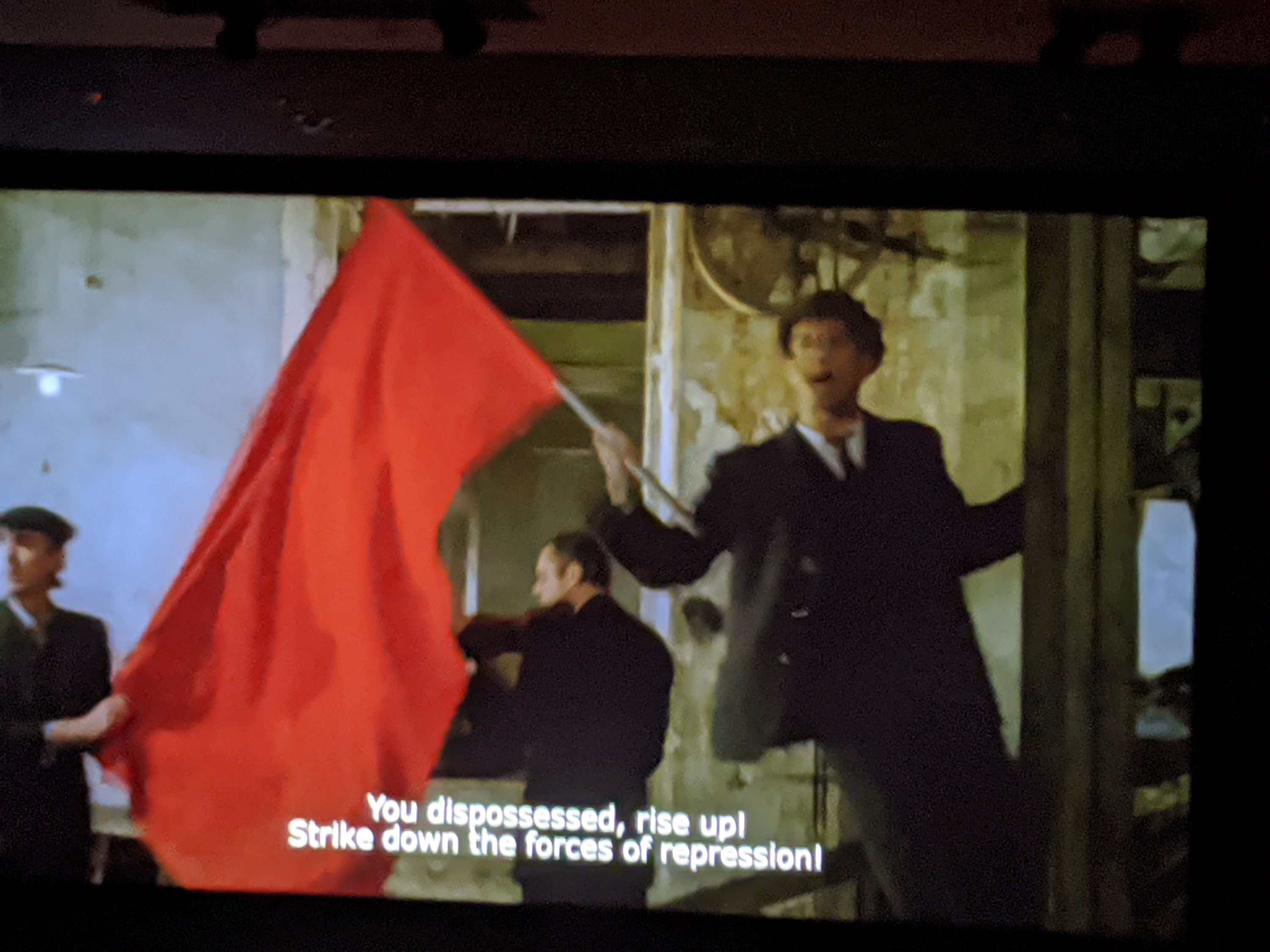

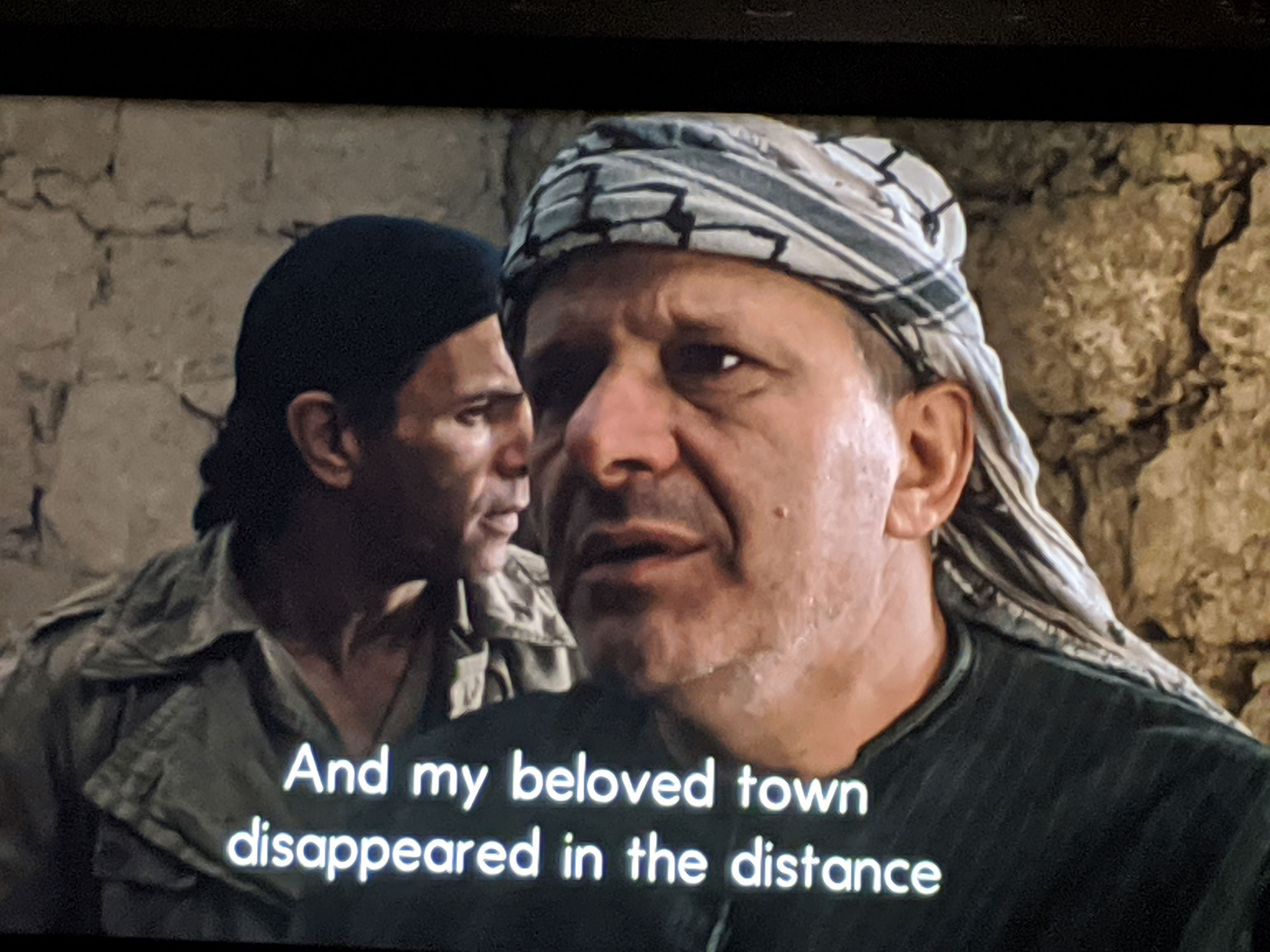

Kedma (2002), recounts a specific moment in time. In the late 1940s, before the end of the British Mandate, the landing of an illegal ship carrying survivors of the Shoah is met with fire by the English infantry. Those who manage to escape immediately join the Jewish armed forces engaged in the battle over land against the Arabs. The contrasting experiences of the refugees-turned-soldiers versus the dispossessed Arabs are crystallized in compelling monologues, based on a texts by the Palestinians writers /activists, Taufique Ziad and Ghassan Kanafani and e by the Israeli novelist Haim Hazaz. The madness of violence and desperation pervade all.

An architect by training, Amos Gitai never formally studied cinema. He says, “I am a graduate of the Kippur War.” What we sense here is a cinema born of an inner urgency, of necessity. Refugees escaping horror in the hope of building a new future find themselves back at war. But how, then and now, can we look at a war movie in a world still at war?

Carmel (2009), is a lyrical, diaristic exploration of echoes from past and present. The film opens with a memorable re-enactment of the Roman siege of Jerusalem, as described by Flavius Josephus in The Jewish Wars. As the film unfolds, it weaves together the letters of Gitai’s mother Efratia, his own experiences in the Kippur war, and a re-enactment of his last encounter with his son departing on a jeep for the Lebanon war of 2006. This personal account (free of nostalgia or sentimentality) projects biographical material against the broad canvas of history.

If the reason for selecting these very different films is the connection to Efratia, her letters and her legacy, what cements them is a common moral tension, or in Gitai’s own words, an underlying civic gesture.

Film stills from: Esther, Berlin-Jerusalem, Kedma, Carmel