Monique Sochaczewski was born and raised in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where she received her PhD in History, Politics and Cultural Heritage from the Fundação Getulio Vargas. Her dissertation became the volume From Rio de Janeiro to Istambul: Contrasts and Connections bewteen Brazil and the Ottoman Empire (1850-1919), FUNAG, 2017. She is the author of many articles and essays on the Middle East and Ottoman presence in Brazil. She is often featured in national Brazilian media on Middle Eastern politics and history. Monique was a fellow at the Bilkent University in Ankara.Since 2018 she has served as Academic and Project Coordinator at the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI) in Rio de Janeiro.

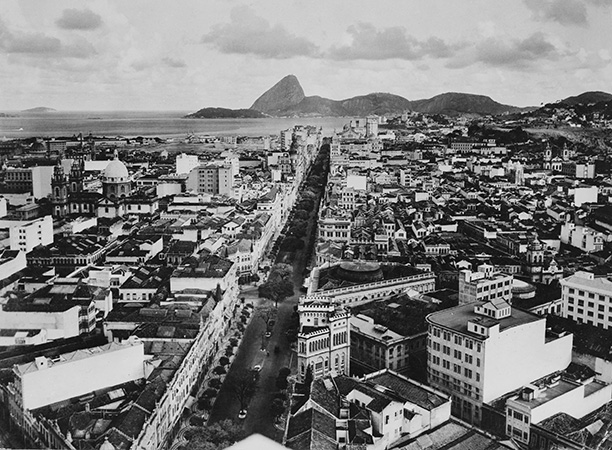

It was from here, from the chaotic, sunny and tropical city of Rio de Janeiro, that most of the sources of Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s recently published book Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey through the twentieth-century (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019) emerged. Stein is a UCLA historian and her herculean undertaking required conducting research in eight languages, nine countries, and on three continents. As it happened, most of the letters, photos, passports, and other documents, that helped her trace the tumultuous journey of Sephardic Jews from Salonica to various corners of the world, were preserved in Rio de Janeiro, at the margins of the world’s geography of power.

The Levys, whose multigenerational saga Stein recounts, followed the path of many Sephardic Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in the late 15th century, who found safe haven in the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottomans complied with the Islamic logic of the ahl al-kitab (people of the book) and welcomed Christians and Jews for much of their history. They organized non-muslim minorities through the institution of the millet: communities that were granted autonomy in the management of their internal affairs. Almost all Sephardic Jews dwelled in other lands before arriving to the Sultan’s domain. This particular branch of the Levys stopped in the Netherlands for some time and, in 1731, arrived in Ottoman lands. Along with their luggage, they brought a printing press. Exactly in those same years, between 1729 and 1743, the Hungarian-born intellectual Ibrahim Müteferrika (1729-1745) was also beginning to print Arabic language books in Constantinople.

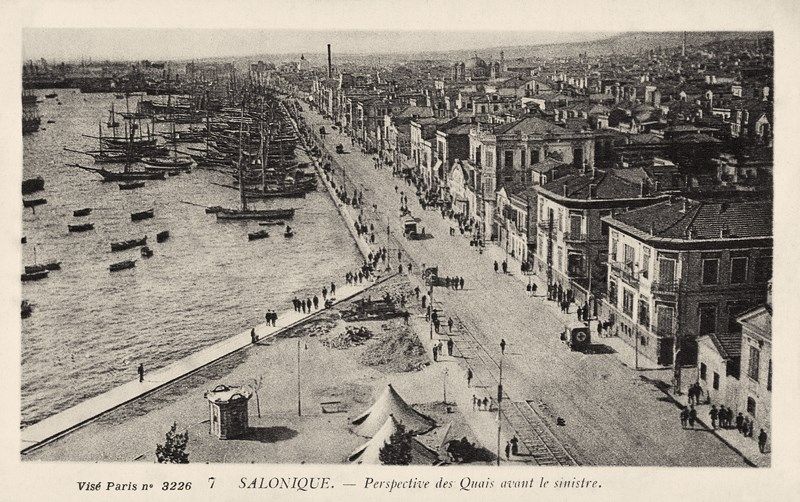

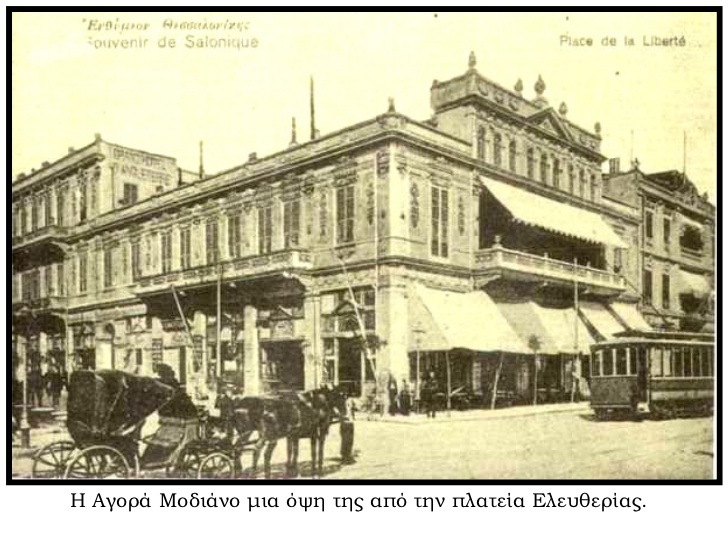

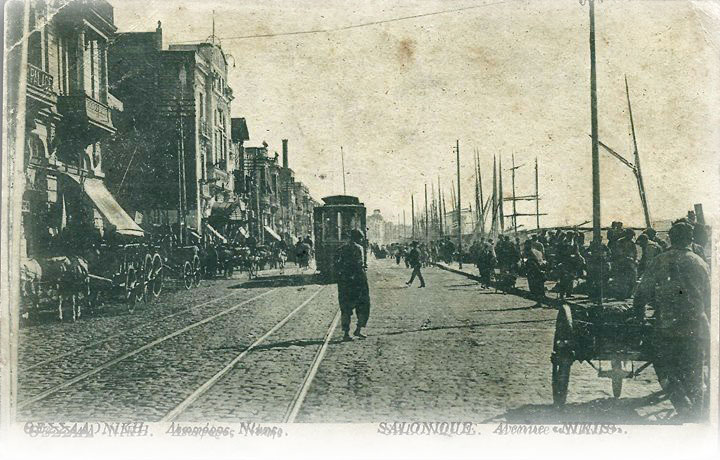

The initial section of Stein’s research focuses on Saadi Besalel Ashkenazi a-Levi (1820-1903), a printer from the Ottoman port city of Salonica at the end of the 19th century. For sixty-five years Saadi produced publications in Ladino, Hebrew, and French. They ranged from wedding invitations to popular newspapers such as La Epoka – for the Jewish audience – and Le Journal de Salonique – for the general audience.A few years ago, the discovery of a manuscript donated to the National Library of Israel by a descendant of Sadi in Rio de Janeiro sparked scholarly interest in the family. It resulted in the book co-authored by Stein and Aron Rodrigue A Jewish Voice from Ottoman Salonica: The Ladino Memoir of Sa’adi Bezalele Levy and published in 2012 by Stanford University Press. From this document and from the connection with the Rio-based branch of the Levy family, Stein began to trace Saadi’s eleven children who reached adulthood, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The chapters of the book take their titles from the names of family members and the saga is divided into sections, each referring to a physical or spiritual geography of inter-personal ties: “Ottomans”, “Nationals”, “Émigrés”, “Captives”, “Survivors”, “Familiars” and “Descendants”.

The Levys witnessed the end of the cosmopolitan Ottoman Empire, the Balkan Wars and the fraught relationship with Greece, which involved traumatic population exchanges in 1923.

The migrations of the family members occurred in waves and over time: towards Muslim countries like Morocco, where some worked for the Alliance Israélite Universelle, towards continental Europe: England, France, Spain, and Portugal, towards Asia: India and Latin America: Brazil. A few of the Levys remained in Salonica even after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the reorganization of the European map as a result of World War I.

Those who remained in their hometown witnessed the Hellenization of this cosmopolitan commercial hub and of its large Jewish community. Under Greek rule Salonika lost much of its prestige and economic power, suffered the occupation of the Axis forces in 1941 and the deportation of most of its Jewish population between 1941 and 1943. The remnants of the Jewish cemetery desecrated during the occupation were used after the war as building material for the new city, including the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, which rose exactly in the place of the old burial grounds.

Stein’s book is dedicated to men and women whose lives were dramatically reshaped by the geopolitical transformations of the 20th century. They moved from multiethnic empires to nation-states. From being autonomous subjects to being citizens of nations around the world. Those who remained in Salonica or moved to countries occupied by Germany or ruled by collaborationists governments, were brutally murdered.

As we follow their trajectories through the pages of the book we become aware of how international events affected personal lives. We can especially appreciate the specific impact history had on Jewish women who lived across cultures. And, like in any committed historical research, we are confronted with the unexpected. In this case, with the controversial figure of a family member who allegedly collaborated with the Nazis and was tried and sentenced to death by the Greek government in 1948.

The Levy’s family relations were maintained mainly through letters that recorded amity, love, quarrels, requests of money, births, and adversities. There were also long periods of silence, especially during the final years of World War II. Leon David Levy (1891-1978), Saadi’s grandson who came to Rio de Janeiro in 1925 and worked in the textile sector, played an important role in reconnecting the family that, especially in its Greek and French branches, had been tragically distraught by Nazi barbarism.

During the war years, Leon worked for the Red Cross in Brazil and sent supplies to Salonica. He was also active in the local Sephardic congregations, helped build institutional life and establish one of Rio’s Jewish cemeteries. He had no idea, however, that thirty-seven members of his family had been killed by the Nazis, including his father Daout and his siblings Eleanor and Emmanuel. It was his uncle Sam, who, back in Paris in the postwar period, helped make contact among the surviving members of the clan. Leon and Sam became the family’s historians for the next generation.

The Levy family records preserved many curious and grandiose stories. The prominence of Daout Effendi, one of Saadi a-Levi’s sons, was helpful to Theodor Herzl when he sought to meet with Sultan Abdul Hamid II and present to him his Zionist ideas. Jacques, the only survivor of the French part of the family, was Isaac Carasso son-in-law. He worked with him in the early days of the yogurt factory that would become the multinational company Danone. A daughter of another cousin who lived in India, Karsa Salem, starred in an early episode of the James Bond series.

Not surprisingly, Stein’s far-reaching reflection could be further expanded. In fact another Sadi, the Brazilian physician Sadi Sylvain/Silvio Levy (1920-2001) cultivated the publishing vocation of the Levys from Salonica. In addition to an extensive academic production, he maintained a column in the newspaper “Jornal Israelita” and published several books including “Medicine of the Bible,” “A study in the book of Samuel,” and “Comparative Hebrew”. The Jewish Museum of Rio de Janeiro and the National Library of Brazil preserve copies of these works. It was Sadi who, in 1977, donated his great-grandfather’s original manuscript to the then Jewish National and University Library in Israel where this historical research began. The tradition continues among his descendants, all of whom have attained solid academic and professional training in different fields.

While delightedly reading Stein´s book, I couldn’t help thinking about another story: Edmund de Waal’s The hare with amber eyes. From a collection of netsukes (Japanese miniature sculptures), de Waal brought to life the amazing journey of the Ephrussi family, from Odessa to Paris, to World War II Vienna. In Parc Monceau, the Ephrussis were neighbors of the Camondo family, Sephardic bankers from Constantinople who moved to Paris in the late 19th century. Today the Camondo’s opulent residence houses the Museum of Decorative Arts Nissim de Camondo. There is a sign at the entrance explaining that the entire family was deported to Auschwitz and perished there. Unlike the Levys, the Camondos did not have anyone left to tell and carry on their story.

But here, in the chaotic, sunny, tropical (and generous) city of Rio de Janeiro part of the Levy family sought a better life in the wake of World War I. It was thanks to that journey that they were spared the barbarism of the following decades. And it was from Rio de Janeiro that, after the war, Leon Levy resumed relations among dispersed family members.

Beyond its many contributions, Stein’s longue-duré approach to a family saga, forces the reader to reconsider values and ideas that, even in the post-colonial and post-orientalist era, have not ceased to permeate historical narratives. The Muslim world lead by the Ottoman Empire was once haven for many Jews who, like the Levys, fled the Spanish Inquisition and the first articulation of the idea of “blood purity”. Brazil, a complex country in restless development, welcomed the Levys, along with thousands of Ottoman Jews, Muslim, and Christians. In Brazil, they found not only business and education opportunities, but also community life as well as integration in the larger society.

As the author herself states, this book helps to catch glimpses of Jewish, Ottoman, European, Mediterranean, and Diasporic history, as well as of stories of women, men and children in the face of war, political upheaval and genocide. What Stein does not spell out, but unfolds from her work in a particularly fascinating way, is that for centuries, since the expulsion from Spain, the Levys’ routes to safety continue to lead away from Europe, whether their destination is the Levant, the Brazilian tropics, or India.

It is through this centripetal force that they built life in the most diverse places, maintaining not only a paper trail and family ties, but sentiments for their culture and a fabled past that, rather than a hypertrophic source of nostalgia, function as a propelling force toward the future.

Images:

Eduardo Kobra, Mural in the port area of Rio de Janeiro, https://www.instagram.com/kobrastreetart/

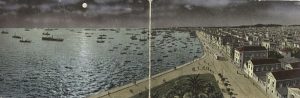

Views of Rio de Janeiro and era images of the city are from the image archive of the National Library in Rio: http://brasilianafotografica.bn.br

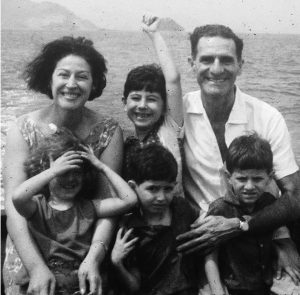

Levy family group in Rio de Janeiro. Back row: Ruth Vieira Ferreira Levy, Silvio Vieira Ferreira Levy, and Sadi Sylvain Levy. Front row: Ruth Nina, Joaquim, and David Vieira Ferreira Levy, c. 1964. Courtesy of the Levy family.

Illustrated view of Salonica, 1910 ca.