Book Review: From Trieste to New York. Annie Cohen-Solal’s Leo & His Circle

Alessandro Cassin

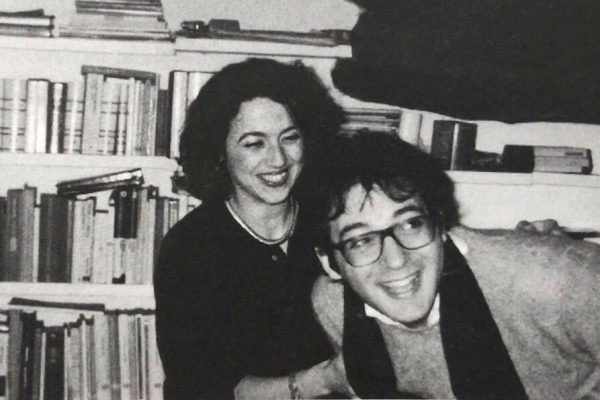

Chances are even those outside the contemporary art world are familiar with Leo Castelli’s name. This slight man, cutting a dapper figure in exquisitely tailored suits, a brilliant conversationalist in at least five languages, has come to be considered the most influential “gallerist” of the 20th Century. Yet for most of the public, Leo (as he was called by all) remained largely a person whose past was enveloped in an aura of mystery, with shadowy areas deliberately left unknown.

As the art world’s center of gravity shifted from Paris to New York, Castelli, identified by many with the emergence of Pop Art and Minimalism, became the first celebrity gallerist. Yet Castelli the man, as is often the case with larger than life figures, ran the risk of being lost behind a self-invented image.

Annie Cohen Solal, in her recently translated Leo & His Circle (Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), attempts to rectify this.

On one hand she credits Castelli with being the catalyst in a major paradigm shift that turned American visual artists into cultural icons, a completely new phenomenon at the time. On the other hand, she goes beyond the smooth old world charm image he had done his best to disseminate and uncovers a wealth of personal and genealogic background. Her extensive research into both paternal and maternal families, the Krauszes and the Castellis, traces a century old “genetic predisposition” toward global commerce, which becomes the skeleton of his psychological portrait.

On one hand she credits Castelli with being the catalyst in a major paradigm shift that turned American visual artists into cultural icons, a completely new phenomenon at the time. On the other hand, she goes beyond the smooth old world charm image he had done his best to disseminate and uncovers a wealth of personal and genealogic background. Her extensive research into both paternal and maternal families, the Krauszes and the Castellis, traces a century old “genetic predisposition” toward global commerce, which becomes the skeleton of his psychological portrait.

Leo & his Circle, which reads more like cultural history than biography in a narrow sense, is also an emblematic tale of the complex and unpredictable ways in which the specific set of values, sensibility, and business acumen of this Italian Jewish émigré shaped American culture and post war European perception and connection to it. Along the way, the book becomes a case study in contrast between what is precarious and what has true staying power. Names and nationalities can be lost overnight but ideas and culture cannot be taken away.

Situated in a territory halfway between a specialized biography and a popularizing tome, Cohen-Solal’s book, a bonified page-turner, maybe a preview of a new type of editorial product of the near future. Researched in depth in many countries and languages by a battalion of assistants (23 are acknowledged), the book does not attempt to provide definitive answers, but rather proposes a sequence of hypotheses and reconstructions that shed fresh light on Castelli’s background and his impact on the world he lived in.

Based on original research and unearthing a vast amount of documentation, it presents the material in a breezy way, which is able to hold the overtaxed attention span of today’s general reading public.

The author makes rapid switches and connections between the different phases and circumstances of Castelli’s life, from the personal to the professional, the local and the international, Europe and the USA.

Despite a personal connection with Castelli, Cohen-Solal largely manages to stay out of first person narrative. And although she had full access to family, friends and colleagues, refuses to slide into gossip and intrusive personal disclosures.

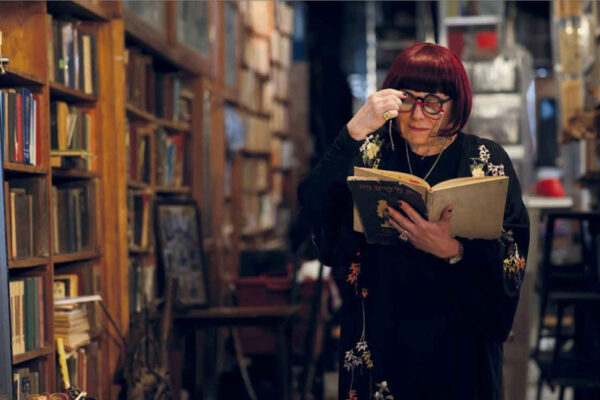

A former cultural counselor at the French Embassy in the USA, Annie Cohen-Solal, presently a professor at NYU, is a critic and historian. She is the author among other works of Sartre: A Life and Painting American: The Rise of American Artists. She divides her time between Paris, Cortona, and New York.

Alessandro Cassin. What do you think were the advantages and the challenges of writing the biography of a contemporary, someone you knew personally?

Annie Cohen-Solal. The memory of Leo Castelli is still very much alive in the minds of American people: he is an icon. People were mesmerized by him and often adored him. I myself was fascinated by his personality, his intelligence, his erudition, his talents and not least by his charm. Everything seemed smooth and light with him, yet I also felt his unrevealed complexity.This combination intrigued me the most. The challenge of working on someone so close to us in time was the necessity to establish a critical distance.

A.C. How did you gain the confidence of those in his inner circle?

A.C.S. Once they understood the scope of my research, many people were eager to talk and very generous with their time. The people who worked at his gallery saw it like a family. They felt cared for and cared for him in return. They recall times when they would not leave the gallery at six o’clock, but call friends and family to party until midnight. Working at the gallery did not feel like work. It felt like they were contributing to something important. In this spirit many people were willing and pleased to go on record in my book as a way to posthumously thank Leo for what he had given them.

A.C. For many, including his own family, Castelli rarely appeared to be “working”. His son Jean-Christophe recalls: “ When I would visit the gallery as a child, I never had the impression that my father really worked. He would talk on the phone, taking his time, he would welcome visitors with a smile, he would disappear for long and leisurely lunches, always courteous and available for everyone. There was never any rush, any agitation, any stress…”

A.C.S. Leo said: “My clients didn’t come into my gallery to buy paintings they could hang on their walls, they came to participate in an adventure”

A.C. He was referring to his clients but don’t you feel that this statement reflects his own motivations as well?

A.C.S. Absolutely!

A.C. Beyond the smoothness Castelli presented to the world you discovered a much more complex personality and set of circumstances…

A.C.S. He was a very private person and there was much about him that nobody knew. I year ago (long before the book was out) I was invited to a biography seminar at NYU and on that occasion I disclosed his discovery of the tragic death of his parents and all that the family had suffered during the Nazi era. The audience, filled with people who had known him for years, was in tears: no one had any idea that his life had been so dramatic. He never mentioned it.

A.C. Leo Castelli, as he emerges from your book, is a man quite removed from his own family. He had lost his parents tragically in the siege of Budapest, did not keep in contact with his siblings, was neither an attentive father, nor husband… yet family loyalty or a sense of clan seems to inform the very make up of his personality.

A.C.S. His gallery was his family! He created a new model of production that was at the same time an economic, emotional and intellectual one. His network of satellite galleries also worked as a family structure with mutual dependencies. He did function as a clan leader, absolutely. And his knowledge and charisma gave status by association to a lot of people. To quote just two: the philanthropist Eli Broad claimed “I was educated by Leo”, and the artist James Rosenquist recalled “people understood that I was not a bum because I was with Leo”.

A.C. Among the many things Castelli did not talk about was his being Jewish, yet reading your book it is hard to escape the sense that his career was defined by a Jewish sensibility and a distinctly Jewish way of navigating the world.

A.C.S. As Professor David N. Myers recently pointed out to me “ You can escape Judaism by converting, but Jewishness you cannot escape”.

A.C. Leo Castelli, as you say, is an American icon, one of the most recognized names in the contemporary art world, a celebrity. Labels like art dealer or gallerist (which he preferred), do not do justice to his cultural contribution. What were some of his main achievements?

A.C.S. When Castelli arrived in the US, this was a country that did not value its visual artists. Contemporary painters were considered second-rate citizens. Writers were valued, but visual artists were another matter. Jackson Pollock and William De Kooning were literally living from hand to mouth. Castelli took visual artists and made them into cultural heroes. (He did this by transplanting here his European and Jewish values and capitalizing on the unique opportunities that US could offer).

A.C. Your research into his maternal ancestry brought you to Monte San Savino. The story of the Castelli family and of the Jewish presence in this small Tuscan town reveals the level of anti-Semitism in XVI and XVII Century Italy. Cosimo III (Grand Duke of Tuscany between 1670- 1723) forced all members of “the Jewish nation” to wear a distinctive symbol, yellow or red, sewn on their clothing.

You portray the experience of the Jews in late Renaissance Tuscany as a mix of persecution (even the tiny Monte San Savino had a ghetto), economic opportunity and social mobility.

A.C.S. After the expulsion from Spain many Sephardic Jews arrived in Italy where the Pontifical State rejected them and forced them to work mainly in the money lending business. They heard that Monte San Savino had special privileges: because one of the sons of the city had become Pope, it was spared the burden of paying taxes on the import of products. Therefore a group of Jews went there and established one of the first Banco di Prestito (lending institution). It is emblematic that they established it in Loggia dei Mercanti, a beautiful architectural structure by Sansovino, directly facing the castle, symbol of the power that had rejected them… It’s worth noting that the arrival of the Jews in the small town of Monte San Savino brought about a vital push toward economic dynamism.

A.C. The Jews left Monte San Savino in 1799, never to return. Are there any traces of their presence left there today?

A.C.S. Everybody I interviewed there told me: “ abbiamo tutti sangue ebraico qui” (we all have Jewish blood here). The local community abounds with stories and anecdotes of sexual mingling and intermixing.

A.C. You describe the variety of the Jewish experiences in this small town spanning from happy times of economic opportunities to times of intolerance and persecution, in itself a snapshot of the Italian Jewish experience at large…

A.C.S. There were Jews who felt protected by the ghetto, others who decided to leave when the ghetto was established and others still who were rich enough to enjoy privileges and exemptions. All of this was both granted and restricted by the rulers and the Church.

A.C. Even in Tuscany the Jews enjoyed the protection of the Austro-Hungarian Emperors and were punished for their sympathies toward the French…

A.C.S. When the French Army invaded Tuscany the Jews were quick to show their allegiance. As the French were pushed back, the Jews became scapegoats for the small clergy and peasants who had opposed the French and the modernization they brought. In towns and small urban centers the Jews were generally well tolerated and often welcomed by the civil society, until they became specifically targeted by reactionary forces as agents of change.

A.C. Leo Castelli urged you to look for his family tombs in the Jewish cemetery of Monte San Savino. Do you think he knew that centuries ago the Castellis had been involved with producing paper for artists there?

A.C.S. I really don’t know. Certainly in the Castelli family people were still talking about their origins in Monte San Savino and of having been protected by the French. There was a deeply rooted francophilia. Memory carried over for generations: they all knew something about that town but nobody, including Leo, went back there. He would often go to Arezzo to visit Piero della Francesca frescoes, but never took the extra few miles to Monte San Savino.

A.C. Leo Castelli was born Leo Krausz in Trieste in 1907. As you point out, Trieste was at the time the third city of the Austro- Hungarian Empire – with a distinctive culture and cosmopolitan population. Ultimately, the reasons that had brought the Castelli and Krausz families to Trieste (persecution, economic opportunity, perceived tolerance, etc.) parallel those that brought Leo and Ileana to New York many years later.

A.C.S. To understand how his family got to Trieste and how Leo eventually got to New York, the key concept is displacement. His whole life history is bound up with a series of displacements. What followed were a series of forced and very rapid adaptations and new beginnings. Trieste was a city of crossroads at the time, the seismic epicenter of Europe. From Trieste one could gage the pulse of the whole Austro-Hungarian Empire, its moods, its cultural and economic trends on the verge of its collapse. Trieste drew its wealth from its geographic location as a harbor. What attracted Leo’s father to this thriving city was economic opportunity: fortunes were being made there. Ironically, when Ernesto Krausz established himself professionally, it was already the beginning of the end for Trieste.

A.C. With the Italian Racial Laws of 1938 the family had to give up the “foreign” last name Krausz and adopt Leo mother’s maiden name, Castelli. For Leo a first concrete example of the precarious nature of identity…

A.C.S. Like many other Italian Jews, they had not anticipated the mounting anti-Semitism of the regime. His father had even joined the Fascist party late and for opportunistic reasons.

A.C. Witnessing the rise and fall of Triestine banking and insurance businesses provided the young Leo with both a blueprint for a global business model and an indelible warning on the ever-shifting political and economic basis of power… Can you elaborate on how this shaped his later life?

A.C.S. Having seen how things big and small came to an end helped sharpen his reactions through quick rethinking of strategies in a whirlwind of inventiveness. “Let’s find a new genius every week… Let’s open a warehouse in Harlem because Richard Serra is working in large formats, let’s move to Soho…” Geography becomes essential: that is why I included four maps, one showing the displacement of the family, one of Europe, one of the US and one of New York. (To Leo cartography was a strategic tool.) Soho, his last destination, became the center of the art world in much the same way as Trieste had been the center from which the commerce of the Austro-Hungarian Empire reached the rest of the world.

A.C. You describe his relationship to his father as not particularly close, yet the two had a lot in common. Ernesto Krausz belonged to a different world, yet the son seems to have adopted many of his traits: professionally self-made, the ability to rapidly feel at ease in different cities, countries and languages, using marriage for upward mobility and social acceptance in new environments…

A.C.S. The more I researched, the more I saw similarities, but naturally there were also important differences.

A.C. He used to give Leon Battista Alberti as his model, yet successful mercantile and banking Jewish families like his own and Ileana’s became his real models. Through a process of distancing, not quite of denial, he incorporated all of that into his own ventures…

A.C.S. I read in a book about Italian merchants of the Fifteenth Century that their way to train young men was to have them study four years of law at the University, then fare tirocinio (become apprentices) with a friend of the father’s. Which is exactly what Leo did… reluctantly.

A.C. Apparently by coming to the US, Leo made a radical break with his past, yet your book presents evidence of a number of more subtle signs of continuity.

A.C.S. He wanted to show a break, but there was continuity. He presented to the world a smooth yet opaque image of himself, but beyond that there was continuity indeed, that’s the reason for the first 200 pages of my book.

A.C. The tragic European history of the ‘30 and ‘40’ taught him that names, borders and identities were shifting and malleable entities… As he later turned himself into an American, one of the things he left behind was his Jewish identity. How do you explain this?

A.C.S. I think it was his way to reinvent himself against the pull of the past. The US presented him with a chance to be free, which meant also free of his past.

A.C. You quote Jean -Christophe as saying “My father never talked about the fact that he was Jewish”. In fact many people in the art world knew nothing about his past, yet so many of his close associates in New York were Jews: Alan Salomon, Leo Steinberg, Bob Elkon, André Emmerich and many more.

A.C.S. It was a fact that most people in the New York art world -except for the artists – were Jewish. What I would argue is that Castelli created a locus where he brought together three very different demographic groups: the European Jewish émigrés (critics and intellectuals), his artists who were not Jewish, many of which came from the South and the industrialists (the collectors) many of which were indeed Jewish.

A.C. Under Alan Solomon’s directorship the Jewish Museum became one of the most daring and avant-garde friendly institutions…

A.C.S. And one of the remarkable things was that in their wholehearted commitment to the art, they did not hesitate to show non – Jewish artists as well.

A.C. Castelli started his professional life in the art world at 50 and from that point on he became unstoppable. Undeniably his strength had much to do with his capacity to surround himself with remarkable individuals, to create a community around him. To describe him you coined the term “bridger”…

A.C.S. He knew how to connect, translate and bring together the European and American value systems. On a personal level he was a networker: his languages, his charm and human curiosity allowed him to establish direct personal connections with an extraordinarily wide range of people. The sharpness of his mind allowed him to remember and put together events and people like no one else. In a sense he was like an agent for the Medici during the Renaissance. His genius was in bringing people together: a museum director with a critic, a collector with an artist, an artist with a writer. Ultimately what was unique about Leo was not his mercantile genius but his conviction that he was serving a higher cause.

A.C. You describe Castelli’s intense relationship with MoMA’s first director, Alfred Barr, almost as search for a father figure…

A.C.S. As far as father figures, Leo already had Ernesto Krausz and Mihai Shapira (his father-in-law), two models of Ashkenazi industrialists. Krausz was a social climber not at all politically aware, an opportunist who used to go with the flow. He failed to anticipate what was coming and ended up in a common grave rather than in the marble mausoleum he had planned for himself. Mihai Shapira on the other hand was a very shrewd businessman who sensed danger before it arrived. He was one of the very few Jewish industrialists who was able to take his fortune out of Romania, first to France and then to the USA and save both his family and his wealth. Two very different trajectories: Shapira always ahead of historical events and Krausz always following them. Regarding Alfred Barr, Castelli made no secret of the fact that meeting him had been the single most important event upon arriving in New York. He told me that walking into MoMA he realized that the collection that Barr had assembled was “ an encyclopedia of European art such as no European Museum could have displayed at the time, because Europe was at war”. Barr had brought together the Russian Futurists, the German Expressionists and the French Surrealists. What Castelli found in the permanent collection at MoMA was the integrated Europe that he had always longed for. In Alfred Barr he saw a man whose intelligence could piece back together the fragments of a continent torn by a devastating war. As a place of advocacy for modernism, MoMA became his university and Barr his mentor.

A.C. The relationship was somewhat reversed as Castelli later introduced Barr to Jasper Johns and other American artists. As the American museum director had revealed to Castelli the treasures of European avant-garde, now the European gallerist introduced Barr to American artists…

A.C.S. Castelli and Barr deeply respected each other and learned from one another. Yet their trajectories could not be more different, for instance Barr was a precocious achiever (he became director of MoMA at 27) and Castelli a late bloomer.

A.C. In 1989 Leo Castelli donated one of his most prized possessions to MoMA: ”Bed”, 1955 by Robert Rauschenberg. He had bought the work in Raushenberg’s first show for $1,100, it had by then reached a market value of $11 million. A highly significant gesture whose meaning you explore in the light of Barr’s symbolic status as a father figure…

A.C.S. The importance of that gesture cannot be stressed enough. At the time the tax laws had changed and Castelli was not receiving any benefit from the donation: he was making a statement, setting an example. He considered “Bed” a masterpiece and was proud to have it become part of the collection he had loved and admired the most.

A.C. The closing of yet another circle…

A.C.S. Incidentally, Alfred Barr, the son of a Protestant minister, had been the best student of Paul Sachs’ at Harvard. Sachs (of the Goldman Sachs family) was one of the most prominent professors of museum studies. This field had been started at the university by German Jewish banking families in order to create museums in America. Sachs had been Barr’s guide, Barr became Castelli’s guide…

A.C. You describe the various stages of Castelli’s career in terms of territorial expansions, alliances, truces and betrayals, followed by negotiations and redrawing of the maps: again a trajectory that parallels that of the European history he learned first hand as a young man in Trieste…

A.C.S. He managed his satellite galleries as if they were states. He conducted business as if he were a statesman. He was an empire builder. That’s why he enjoyed so much the simile I drew between him and the House of Savoy. Yet he was never after the money, but rather the symbolic power.

A.C. Castelli operated in the new economic climate of the 1960’s where he rapidly became an arbiter of a new value system, a complex economy of cultural objects. How did this happen?

A.C.S. After the war the US economy began to grow, there was money to be made and money to be spent. Castelli understood the opportunities presented. His knowledge of the arts and historical sophistication allowed him a privileged position. He was able to establish and validate the cultural and monetary value of new art. He turned art collecting into an activity that could give status and prestige as well as visibility. He was a great sorcerer…

A.C. Going back to your idea of a “bridger”: Castelli started a circular exchange of art and ideas between Europe and the US. In the sixties he introduced American artists in Europe and eventually brought European artists to the US. Do you see anybody today being able to continue in his footprints…

A.C.S. Leo Castelli was one of a kind. Many of his collaborators and colleagues have picked up some of his traits, but no one possesses his unique combination of qualities. As the art world expands, the real question is who will be the Castelli’s of tomorrow, bridging Europe and the US with China, the Far East and the rest of the emerging world?