Letter to a Friend in Gaza: From Film to Theater

Amos Gitai’s stage version of Letter to a Friend In Gaza, which had its World Premiere at Spoleto Festival USA in Charleston on May 29th, is an absorbing, demanding, thought-provoking, and lyrical multimedia work. In times of “art-as-entertainment”, it restores confidence in the theater’s capacity to pose politically and culturally loaded questions. It shakes an audience out of passivity, leaving us with the challenging task of measuring the theatrical experience against our thoughts, perceptions, and prejudices on the Israeli/Palestinian conflicts. Rather than offering a thesis or solution, it acts as a powerful trigger for a, much needed, “political imagination.”

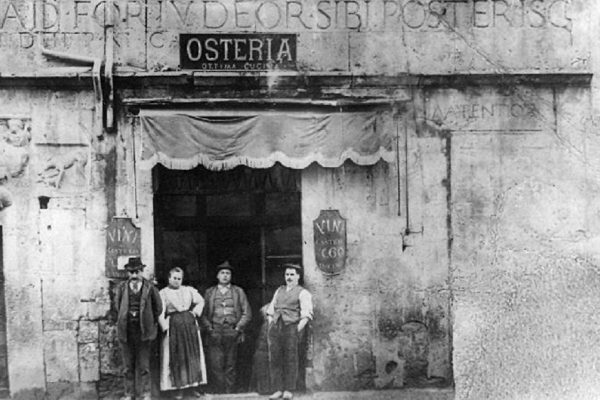

Originally, A Letter to a Friend In Gaza was a 34-minute film, shown at the Venice Film Festival in 2018, where Gitai’s latest feature, A Tramway in Jerusalem, also premiered. “Some months ago I had shown Nigel Redden, General Director of Spoleto USA, my non-fiction short, A Letter to a Friend In Gaza and he suggested I worked on a theatrical version for Spoleto,” said Amos Gitai.

The film and the theatrical version share much of the same texts and cast, yet paradoxically, the structure and feel of the film, seems more theatrical —carefully staged medium shots of four actors, in pairs, reciting and listening to poetic texts— while the broader horizon and multi-layered composition of the 1 hour and 30 minutes theatrical version seen in Spoleto, felt more cinematographic.

As the play begins we are confronted with a barren stage, the only object a long wooden table, dividing the space horizontally. The table with chairs, microphones and reading lamps, evokes that of an academic conference, or of international peace talks. Upstage the area ends against a giant film screen. Lights down and the screen is flooded by high impact scenes from the Romans conquest of Jerusalem, in 70 CE. A newscast-like voice off-screen, recites fragments from Flavius Josephus (a quotation from Gitai’s 2009 Carmel). It is a brilliant piece of pyrotechnics- montage, which gains from the scale of the screen. With no respite, we are then swept by the sound of a helicopter as we survey from the air a tank battlefield area in the Golan Heights, in 1973 (a quotation from Gitai’s Kippur, 2000), contextualizing what will follow —a passionate meditation on the current plight of two million Palestinians locked up in Gaza— in the centuries-long history of conflicts that have afflicted this war-torn area. The play seems to suggest, from its opening, that to look at the situation in Gaza today, we must look at the conflicting histories and competing memories that have brought us here.

The past, rather than having happened once and for all, informed by the present, determines both our present and our imagination of the future. All of this unfolds, progressively, through allusive texts intelligently woven together into a sort of “poetics of politics.”

Enter the players: two musicians, Bruno Maurice on accordion and Vahid Mazdeh on tar and setar, seated upstage, but often circling the table while playing, and four actors: two Palestinians, Clara Khoury, Makram Khoury, and two Israelis Rivka Gitai, joined toward the end by the director himself. In addition, in one dramatic moment, Madeleine Pougatch takes the stage with great emotional impact in a protracted scream/lamentation accompanied by the accordion. Like at a peace conference, a seder, or a family dinner, the four, seated at the table, in turn read/recite stunningly beautiful texts in Arabic and Hebrew, their respective languages (which the audience can read in English subtitles on the screen).

Makram Koury with commanding stage presence, speaks verses from poems by Mahmud Darwish, (1941-2008) considered the poetic voice of the Palestinian people, as if he were actually thinking them, here and now. Rivka Gitai, a professor of literature, delivers her lines with conviction, whether from literary text or from compelling journalism. She begins with a section of the novella Khirbet Khizeh a novella by S. Yizar (pen name of the writer and politician Yizhar Smilansky) from 1949, in which he recounts the Israeli soldier’s displacement of the entire population of a conquered Palestinian village:

“Burn- blow up- arrest […] with such courtesy and with a restraint born of true culture, and this would be a sign of a wind of change, of decent upbringing, and, perhaps, even of the Jewish soul, the great Jewish soul.”

The delivery of each text is amplified and made solemn by the attentive gaze of the other actors around the table, their “heightened listening” palpably joined by the audience. On the big screen, selected emblematic images from the film alternating with close-ups of the actors, reciting or listening, captured by small surveillance cameras placed on the table and re-mixed onto the screen.

Clara Khoury’s delivery Think of the Other by Mahmud Darwish, at once soothing and uncompromising, stays with you long:

“As you prepare your breakfast, think of others

(do not forget the pigeon’s food).

As you conduct your wars, think of others

(do not forget those who seek peace).”

Listening to the poetic texts in Arabic and Hebrew, the similarities between the musicality of the two languages become apparent, while describing a reality from diverging vantage points. The music, with the text and the projected images, create a multidimensional time and place, the cyclical wondering of the musicians around the table, reminiscent of the hands of a clock and thus the passage of time.

An important aside, under the current administration’s restriction on visas, the chosen musicians, the Russian Born violinist, Alexey Kochetkov, the Berlin-based Syrian oud player Wassim Mukdad, and the Iranian born santur player Kioomars Musayyebi were denied visas, despite the invitation from a well-established festival such as Spoleto USA.

Though each text carries inescapable weight in the play, the show stopper for me was another poem by Darwish How many times will it be over recited as a dialogue by Clara and Makram Khoury (daughter and father in life as well):

“Are you speaking for me, father?

They signed a truce on the island of Rhodes, my daughter

What about us? What about us, father?

It’s over…

How many times will it be over, father?”

During their dialogue, while the daughter sits in profile at the end of the table and the father facing the audience the projected images of their faces in the video are shown both facing us — the emotional space collapsing the physical space—

The long struggle of Israelis and Palestinians over a sliver of land in the Middle East acquires at times a more universal significance, most poignantly when Some People a poem by the Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska is recited by Clara Khoury:

“Some people fleeing some other people.

In some country under the sun

and some clouds

[…] and concludes

Something else is yet to happen, only where and what?

Someone will head toward them, only when and who,

in how many shapes and with what intentions?

Given a choice,

maybe he will choose not to be the enemy and

leave them with some kind of life.”

The pathos of this visually mesmerizing multimedia presentation lies in the intertwining of texts with the live music. While the tar and setar, introduce Middle Eastern melodic material, the accordionist creates tapestries of sound, at times through percussive gestures, other times by compressing and expanding the bellows without pressing the keys, thus producing a haunting “breathing” sound.

Individually many fragments of the texts could stand alone and describe the mood of the play. Amira Haas, an Israeli journalist who has been covered the Occupied Territories since 1993, wrote a memorable article that begins with:

“Maybe the day will come

and young Israelis

Not one or two, but an entire generation—

Will ask their parents:

How could you.”

And yet the power of Gitai’s piece lays in the “dialogue” between of texts written over roughly 70 years, and stunning juxtaposition of all the other elements: music, film video and acting.

The last text, which inspired the piece’s title, read by Amos Gitai, is Albert Camus’s Letter to a German Friend, written in 1944. Camus had what Gitai refers to as the political foresight or the capacity to imagine how as Frenchman, he will one day, after the war, be able to relate to a hypothetical German friend.

Until Israelis and Palestinians do not imagine their post-conflict dialogue, peace will continue to elude them.

Neither the film nor stage production of Letter to a Friend in Gaza attempt to offers solutions, but certainly provide much to ponder over. Opposing views, histories, and memories require deep listening. Jews survived in an often hostile diaspora, thanks to their clinging to their history and to their collective memory. Now in Israel, they are confronted with the plight of another minority, with a different past and collective memory. Can they afford not to listen?