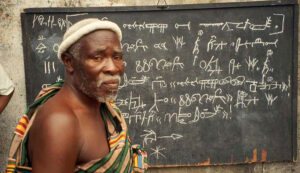

From One Language to the Other was broadcast by one of Arte’s evening shows dedicated to languages together with a 17-minute documentary filmed in Africa, Bruly Bouabré’s Alphabet. This short film was dedicated to the invention of a form of African writing by Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, born Gbeuly Gboagbre in 1923, in the Ivorian village Zépréguhé. Now a wise, old, white-bearded man, Bruly Bouabré explains the grammar of his pictograms, created over the course of the 1950s by drawing hundreds of monosyllabic words of his native Bété language.

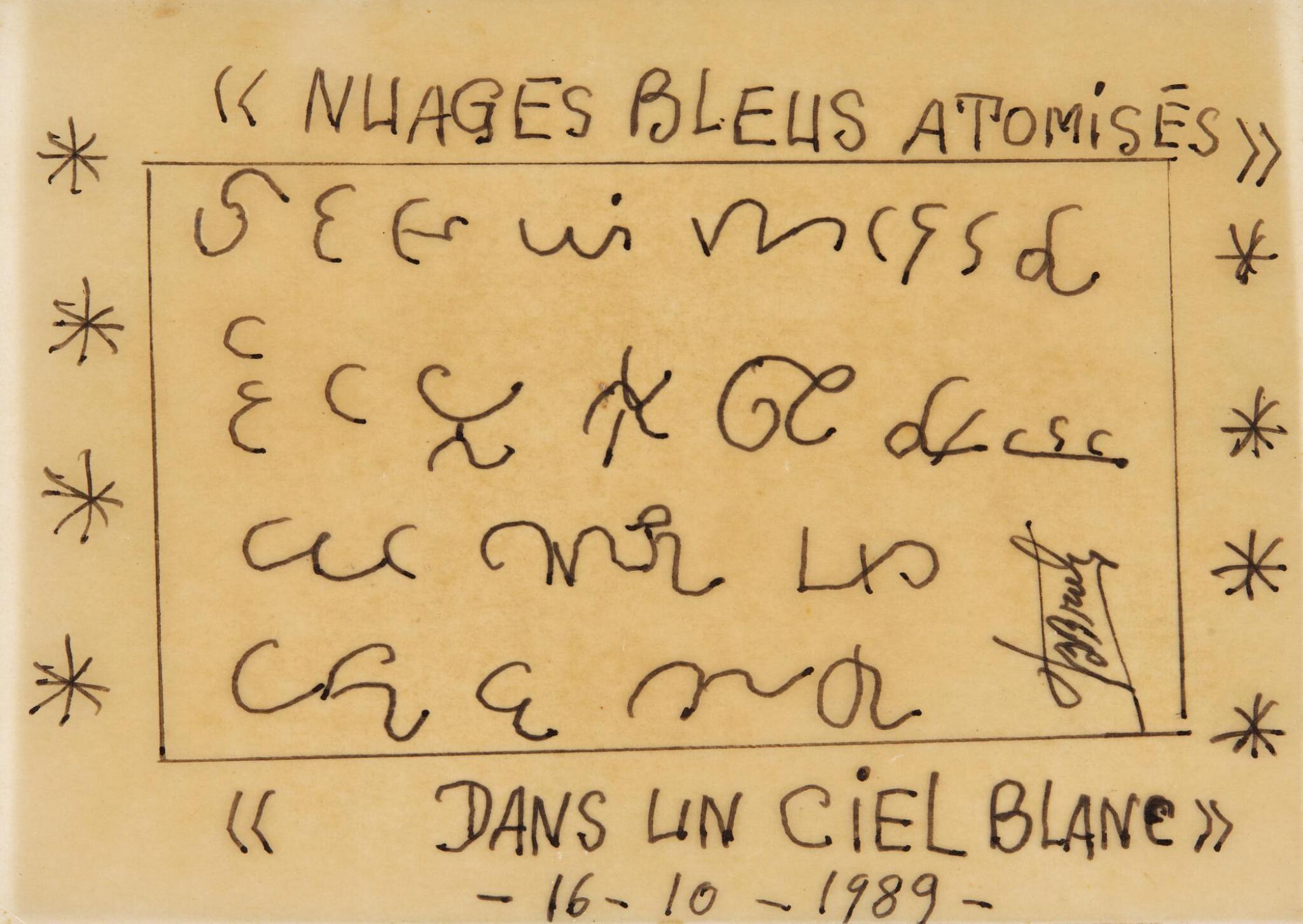

This alphabet was in fact a syllabary of 448 signs, each one drawn and colored on a small, 15cm square of carton, torn from hair-extension packaging, decorated with geometrical forms, inspired by stones observed in a neighboring village. But his initial dream was vaster: “To find on the scene of human life a specifically African writing: such is my desire.” It is this “scene” the movie deals with. The film poses the question of translation as a passage from the spoken to the written, and that of the hazards of intercultural exchanges, by way of a sketch. The film focuses on this linguistic discovery without mentioning the mystical inspiration of Bruly Bouabré, who said he had received a prophetic revelation when he was clerical officer for the Administration of the Dakar-Niger Railroad Line: on March 11, 1948 the sun split itself into seven colors and opened for him the sky, revealing to him that he was a Prophet. He then chose to call himself “Sheikh Nadro, the Revealer,” “he who does not forget,” and, quitting his job at the railroad, he dedicated himself to saving the Bété culture by putting it down in writing, this passage being conceived as a gateway to the universal. He began telling the stories of the Bété people, to record their myths and rites but also their daily lives, alongside French current affairs, capturing glimpses of yesterday’s and today’s world in a universe of signs, drawing colonial and post-colonial modernity on the basis of Ivorian scenes and landscapes open to “observations of the clouds.”

This encyclopedic and cosmogonic mission, which led him to draw and color on thousands of cartons which became more and more finely crafted, transformed the linguist-prophet into an artist. Bruly Bouabré’s writing was only practiced by those close to him, but his colorful cartons circulate throughout the world, like the traces of a language dream of which they would have emancipated themselves through art (thanks to the misunderstanding of the label of “primitivism” brought about by the Centre Pompidou exhibition Magiciens de la terre, where the work was revealed to the public in 1989). Through the discovery of these cartons, where the image formed writing, Nurith Aviv gathered information, investigated, visited the dreamer.

The film mentions a letter from Boubré to Théodore Monod, in which he explains to him that he wants to give the Bétés an “easy method” and an “amusing system” that would allow everybody to “learn in a short time.” Impressed, Monod signalled the invention of a “new West African alphabet”, in the Bulletin de l’Institut français d’Afrique noire: it was 1958, ten years after Bouabré’s enlightenment, and it was the first step of a journey of international recognition—initially ethnographic before becoming artistic—which made Bruly Bouabré one of the greatest bridge-builders between the African and European worlds, before he became an established name in global contemporary art. Since his revelation in Les magiciens de la terre in 1989, this oeuvre has been shown as such at the international exhibitions and biennials of Venice, Paris, São Paulo, Dakar, Istanbul, Moscow, and Kassel, in the great contemporary African art exhibitions (Out of Africa, Africa Remix) and, a year after his death, in 2014, the MAMCO of Geneva devoted a major exhibition to him under the title Connaissance du monde, which was borrowed from him.

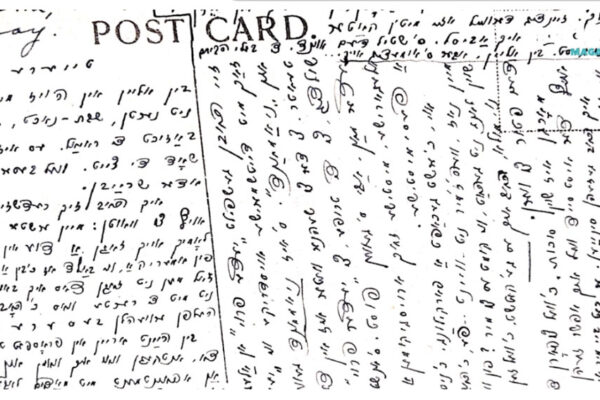

Though absent from the film, Bouabré’s enlightenment on March 11, 1948, was nonetheless undoubtedly engraved in Nurith Aviv’s memory: she herself was born in Palestine on a March 11, three years earlier to the day, and 1948 was the year of the founding of the State of Israel! Bruly Bouabré’s enlightenment recalls that of Ben-Yehuda in 1879. But for one, it was a question of writing down a spoken language in order to save it, and on the other hand to speak a written language that had become holy in order to gain existence among nation-states. For both, language was a mode of inscription into the world and of resistance to erasure. Four years after Bruly Bouabré’s Alphabet, the film Sacred Tongue, Spoken Language [in Hebrew Leshon kodesh, sfat chol, “Sacred Tongue, Profane Language”] came out, wherein the Hebrew alphabet is acted out by a woman reading from the Book of Creation [Sefer yetzirah], the foundational book of Jewish theology of the name and kabbalistic mysticism.

When, in 2009, Nurith Aviv was awarded the Édouard Glissant prize for From One Language to Another, Glissant, having also seen Bruly Bouabré’s Alphabet, recalled that the children of Black Africa necessarily spoke several languages—those of the clan, the nation and the dominant lingua franca—without the conflict for this reason becoming a “confrontation.” He recalled that Bouabré’s approach was that of “someone whose language is disappearing,” something that happens every day in Africa. The Alphabet showed that it was possible to act on a language, to change it by associating with it another symbolism, even one that was difficult to integrate. From One Language to Another showed that a language can also “multiply itself in another,” “restructure itself in another,” that one can “help and revive another.” Enthralled by this “brilliant” film, Glissant insisted on its universal dimension: just as the landscapes were those of the world and not of “a place,” the characters each narrating their own lives “all told the same story”: that of the powers and problems of languages, virtually all of them. The greatness of the film, he says, is to show that there is a “point of absence” between languages—and here he takes up the formula used, in From One Language to Another, by the woman he calls the “great young poetess”: the very special (and universal) Haviva Pedaya, whose great-grandfather had taught Kabbalah in Baghdad. (Écrire l’histoire, nº 19, November 2019)

Writing an Eclipsed Language

The 19th and 20th centuries in Africa were marked by what could be called “scriptural entrepreneurship,” born from Africans’ desire to create graphic systems for their languages. The inventors of African scripts wanted in fact to free their native languages from their dependence on Arabic and Latin scripts at the time of their transcriptions. The writing of African languages by Africans has required the invention of syllabaries. The creation of alphabets has been an essential tool in these artistic and revolutionary endeavors. Frédéric Bruly Bouabré created a syllabary for the Bété language, based on vignettes, that was received as an alphabet. This invention is part of the series of writing revolutions initiated by his predecessors: the Liberian neographer Momolu Duwalu Bukele, the Bamoun Sultan Njoya, the Somali writer Osman Yusuf Kenadid, the Malian linguist Woyo Couloubayi and the Guinean pedagogue Solomana Kanté, to name but a few, respectively inventors of the Vai, Shü-mom, Osmanya, Masaba and N’ko scripts. The Ivorian artist Bruly Bouabré wants above all to ensure the continued existence of his mother tongue, to rescue it from the eclipse into which the colonial context had plunged it. In an Ivorian linguistic environment dominated by French, Bruly’s project of graphizing Bété has proven to be linguistically salvific.

It’s almost certain that if you asked the first Bété you run into to transcribe into Bruly Bouabré’s “writing” what you say to them in French, they won’t succeed. The reason is that the artistic and linguistic creation of the Ivorian artist is not taught in Côte d’Ivoire’s schools, colleges, and universities. Even within his own ethnic group, it is difficult to find a woman, a man or a child who can write Bété using the syllabary invented by Bruly Bouabré. To make the pictograms that make up the syllabary one’s own, a prior initiation is required, which is not accessible to the general public due to a lack of popularization. If Bété had benefited from the privilege enjoyed by the French language on Ivorian soil, there would be thousands, if not millions, of Ivorians who could easily use the prophet-poet’s writing system.

The Ivorian artist’s pictograms do not constitute a complex whole, as one might think at first glance. The Latin spelling used, essentially composed of capital letters, has a phonetic value. It helps the uninitiated reader to pronounce pictographic signs. These figurative drawings are not the fruit of mere individual imagination. The linguist-designer associates them with his divine and spiritual experience. On the borderline between the artistic and the prophetic, his creation crosses the verbal register, that of drawing and that of writing. His work has been described as “encyclopedic.” In reality, his propheticism includes a refusal to be considered “erudite” and a marginal relationship with the scientific world.

Reading anthropologist and naturalist Théodore Monod’s text on the work of the artist-prophet one learns that he was inspired by the engravings on the “mysterious” stones of Békora, a rural town in the center-west of Côte d’Ivoire.

Although what has been called the “Bété alphabet” emerged during the colonial period, Bruly Bouabré did not use it as a tool to oppose the writing of French in Côte d’Ivoire. The fear of the increasing precariousness, or even the disappearance, of his native language remained his major concern, which he tried to convey to his people.

The Visual Effect

Getting Bété speakers to recognize the need to use the pictographic syllabary invented by the prophet-linguist remains an arduous task, especially as Bété is neither a widely-used language nor a profitable one. Initiation into Bruly Bouabré’s schematic drawings is perceived as a thankless activity, which explains the failure of the alphabetization sought by the Ivorian artist (associated with his prophetic mission) through his writing of Bété. This setback contrasts, however, with the international success of his graphic work, exhibited in various countries around the world. In the prophet-designer’s writing, drawing is not only a purveyor of meaning; it is also adventurous, marvelous, joyful.

Nurith Aviv’s superb documentary Bruly Bouabré’s Alphabet, made in the early 2000s, traces the daily life of the Ivorian artist in his Abidjan home. We see the aged body of the poet-prophet initiating a few of his relatives to writing and reading his alphabet. His writing and linguistic production were not enough to make Bété a language of culture on par with French. In Côte d’Ivoire, Bété is neither an official language, nor an administrative language, nor a language of instruction. Bruly Bouabré’s invention of a writing form has failed to spread beyond his family. French remains the country’s only official and teaching language. Its overwhelming influence contributes to the “confining” of Bété, comparable to that of other Ivorian ethnic languages on their own soil. This situation is common to most formerly colonized African countries, which have adopted French, English, Portuguese, or Spanish as their official languages.

Bruly Bouabré’s pictography retains the punctuation marks of the French language. It has not entirely freed itself from Latin writing conventions. With the exception of Pharaonic Egyptian, Ge‘ez, Meroitic and Berber, all of which had independent graphic systems, the inventors of African syllabaries have borrowed from Arabic and Latin to make their own graphic inventions legible. Nurith Aviv’s film shows how difficult it is for a prophet-artist to radically separate himself from the Latin alphabet, even if he does depart from its phonocentricity. This fascinating documentary has helped to make known this solar man’s work.

What remains of languages when there is no more language?

Writing an eclipsed language like Bété may seem an act of desperation. The linguist who ventures into it discovers the fragility of languages, the illusion of their purity and homogeneity. He even discovers that they don’t “exist.” Or, to be more precise, that they only exist when caught up in, or even carried away by, the history of languages. What does it mean to speak and write a language that isn’t one, identical to itself once and for all? The Arabization and Romanization of the writing systems of African languages have not allowed for the translation of all the sounds and images that are specific to them. Bruly Bouabré’s pictographic writing gives the impression that the language is an immense rebus to be deciphered. The prophet-inventor, through his gesture, refuses translation to let his intimate language, the language he has invented, speak. His act of writing is akin to an educational mission with prophetic overtones. He blends there the poetic, the magical, and the playful.

With Bruly Bouabré’s Alphabet, we discover that a language can be known, or even saved from obsolescence, insofar as it is spoken and written, and that to resist the inevitable linguistic cohabitation that threatens its life and internal cohesion, it must continually reorganize itself and spread beyond its original environment.