On this Giorno Della Memoria, Centro Primo Levi remembers the life of Nedo Fiano (Florence, April 22, 1925 – Milan, December 19, 2020), the father of our friend and former chairman, Andrea Fiano.

Nedo was thirteen years old when the Racial Laws forced him out of public school and into a life of senseless punitive isolation. After years of hardship, when fellow Italians turn their backs on Jews, in 1944, he and his entire family were arrested and deported to Auschwitz. Nedo was the only one to survive and return to Florence in 1945.

Soon after, he moved to Milano. After graduating from the Bocconi University, he devoted himself to the textile business and married Rina Lattes with whom he had three sons. At the beginning of the 1980s, Nedo began to bring his experience of the persecution and the camp to school and public institutions. He wrote books, gave lectures and interviews, appeared in Ruggero Gabbai’s groundbreaking film Memoria, the first witness-based documentary on the deportation of the Jews in Italy.

An articulated, intelligent, and powerful speaker, for years, he continued unflaggingly to give talks and help younger generations understand what had happened in Italy during Fascism.

His first book A 5405. The Courage to Live, is a punctual recollection of his experiences at Auschwitz, where that number, A 5405, was tattooed into his arm in an attempt to erase his humanity. But what transpires from those pages, together with the unspeakable tragedy, is his irrepressible love for life and freedom.

Anyone who ever heard Nedo give a talk will remember his commanding presence, thunderous voice, and powerful testimony. His clear-eyed admonitions about the dangers of all forms of intolerance, will remain exemplary.

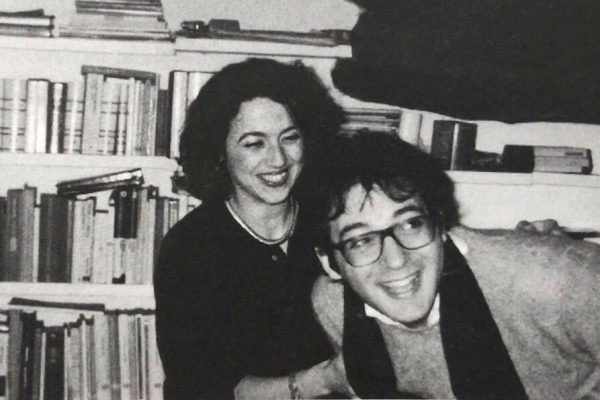

Image: Nedo Fiano and Rina Lattes on their wedding day.

From a talk by Nedo Fiano to students in a school in Lugano, Switzerland, organized by the Association of History Professors of Ticino.

What has characterized my whole life has been my deportation to the Nazi extermination camps. My entire family ended in Auschwitz with me; they were all exterminated. At eighteen, I was orphaned, and this devastating experience made me a different man, a witness for life.

I did not come here to enrich your culture, but if possible, to enrich your heart. And to share with you my thought that perhaps man will be happy on this earth on the day when solidarity will no longer be an exception but will be everyone’s culture. Millions and millions of people cannot be killed again if there is solidarity. Think of those men who have saved hundreds or thousands of people, but I don’t want to make it a question of great numbers, just think what it means to save one person, one.

Saving an eighteen-month-old infant, saving an eighty-year-old grandmother doesn’t matter … The task is all there, in preserving someone’s life. Because then there is a return.

Those who have not offered solidarity, in turn, will not receive it did not have it. Life is a very difficult path for everyone, sooner or later life has a price that we all have to pay.

There are so many Auschwitz in this world. There are so many opportunities to offer solidarity. There is no need to be a hero, no need to be an Arnold Schwarzenegger or a Sylvester Stallone. Common men are enough.

When a car stops at a red light, there is always someone begging for money, at least in Milano. They are often illiterate, dirty. I ask you, what does it cost to put a coin in these people’s hands?

Many don’t, because those hands are dirty … when they take the coin, you see that those hands have calloused, they are full of wounds and have dirty nails. We don’t like to give our help to people unless they are well dressed and have valuable watches on their wrists…

Believe me, solidarity begins with the coin you give. And you will be healed of this evil, the evil of indifference, only when you feel better when you give that coin. That small change that does not impoverish anyone. Those coins that have such an insignificant value to you. What can 10 Cents be to you? But those 10 cents have a different value for them, a value that you see in a face that lights up upon receiving: – “Ah, I found someone who shares in my pain” This is the crucial point. It is not enough to alleviate physical suffering, we must address moral suffering as well. All this and much more teaches Auschwitz.