— Though, we usually don’t review books available only in Italian, in this case, the approach to a familiar subject is so remarkably fresh that I trust will interest our English speaking readers as well as, hopefully, move a U.S. publisher to translate it —

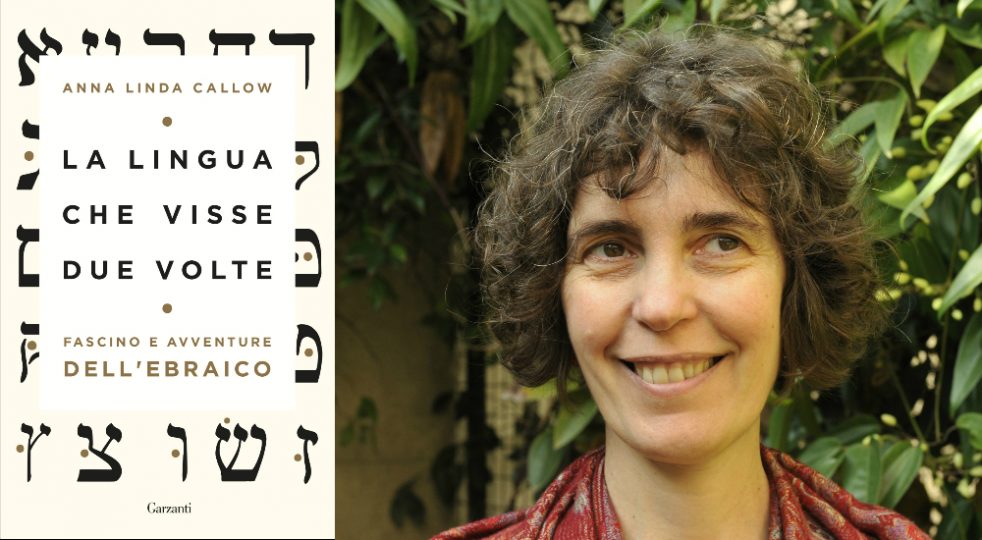

Anna Linda Callow’s new book La lingua che visse due volte. Fascino e avventure dell’ ebraico (The language that lived twice. The Charm and Adventures of Hebrew) Garzanti, Milano 2019, is a passionate and infectious argument for the study of Hebrew and its esthetic, philosophical and cognitive rewards.

Much has been written, about the richness of Hebrew, a language that after surviving largely unchanged for millennia as a sacred and liturgical one, has found a “second life” as a modern spoken language, in Israel. Callow’s approach both timely and topical, may be precisely what is needed for millions of people who at one point or another, have wet their feet in the vast sea of Hebrew, promising themselves to return to it one day.

In her preface, the author ( who is not of Jewish origin) traces her personal encounter—soon to be a love affair— with Hebrew to when at age six, she was fascinated by the language spoken by Haim, an Israeli friend of her father who had moved to Italy. The book, in a sense, is the chronicle of this passion, which has brought Callow to obtain a degree in Medieval Hebrew Philology, and, at a young age to be a distinguished professor of Hebrew Language and literature at the University of Milan.

Today she is also a famed translator from Hebrew, Yiddish, and Aramaic into Italian (she has translated Yosl Rakover Talks to God by Zvi Kolitz; A Simple Story by S.Y. Agnon; This Story Must be Told Masha Rolnikate; The Family Carnovsky by Israel J. Singer among many others.)

The almost daunting task of tracing the history of the Hebrew language, and that of the literature and of the people who have read it or spoke it, is achieved in 214 pages, balancing real scholarship with lightness, enthusiasm, personal anecdotes and the joy of storytelling.

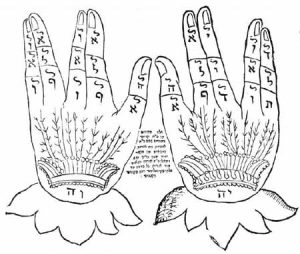

Callow proceeds in great leaps, immersing the reader in this vast territory with the enthusiasm of an explorer. After some general consideration on the impact of Hebrew on different cultures and languages, she introduces just enough details about the Hebrew alphabet – from the 22 consonants to the vowels system, numerical value of each letter and implications whereof— to whet the appetite of the novice or rekindle interest in those already somewhat familiar. Her gift is in introducing material and seamlessly commenting on it, often with original insight. Her vision, always open toward multiple directions is often helpfully comparative: in the Hebrew alphabet she sees a stunning example of: “The beauty of the graphic systems with which men throughout history have chosen to represent their thoughts.”

The language used by God in Bereshit to create the cosmos a God and by Adam to name all living creatures is here presented as a living organism. Languages particularly if not spoken for long, modify, adapt, and interact with other languages.

“The presence of numerous “duplicates” among the consonants is due to the fact that over the centuries the pronunciation has been impoverished. We have lost the distinction between alef and ayn, tet and tav, kaf and qof, samekh, and sin. At the same time, the aspirated pronunciation of ghimel, dalet, and tav has been lost. In order to hear how probably at least some of these sounds were pronounced, we must turn to Arabic to which Hebrew is closely related, and where many distinctions have been preserved.”

Inevitably the reader is presented with some grammatical structures, but even here, Callow strikes a balance between providing the needed information and triggering the reader’s imagination with evocative examples. For example, she explains how verbs (and nouns) are derived from roots, that is from tri-consonantal groups, the shoresh. Once we move to the short and nimble chapters on the Biblical texts, the Midrash, the Talmud, and the Kabbalah, her pointing to a half a dozen roots we are by now familiar with, become the keys to our access to examples of these complex texts.

No matter if only a few readers will reach the command of Hebrew displayed by the author, her book provides everyone the tools to appreciate how much is lost when ancient Hebrew texts are translated into modern languages. As a sophisticated translator, Callow is well aware that mistakes large and small are always lurking: among the more colorful translation errors, she mentions the biblical text describing the radiance of Moses returning from Mt.Sinai. The Hebrew word qeren means both ray- radiance and horn, and translators have often opted for horns. Thus Michelangelo’s famous statue of Moses has horns rather than rays on his head… And yet her faith in her professions (teaching and translating) is unflinching:

”Languages are always learnable, teachable, and translatable because they are born, under all the skies, from a hardcore of similar and communicable human experiences. The differences among them are only nuances. Their absolute permeability is demonstrated by the fact that languages mix spontaneously (to the great horror of the purists.)”

After a fascinating, if cursory review of famous Jewish rebels, cursed personalities, and false Messiahs, we arrive at the second life of Hebrew in modern Israel. Starting from Eliezer Ben Yehuda who compiled a monumental dictionary, raised the first Hebrew-only speaking child, and advocated for the use of Hebrew in the Yishuv, the book narrates the controversy and debates around the resurrection of Hebrew as a modern language. The revival of Hebrew as a spoken language is seen as one of Israel’s great achievements:

“If we look at Israel today, the rebirth of Ivrit is one of the most successful enterprises of that fateful era, more than the Jewish peasant project, for example, which is gradually disappearing. The measure of its success is that in Israel, speaking Hebrew has become commonplace, everyone does it, and as a mass phenomenon has lost part of its prestige.”

With her eye on the movement from biblical Hebrew to modern Ivrit, Callow offers insight also into other languages that Jews have spoken in different times and locations from Aramaic to Yiddish and Ladino. By sprinting her narration with personal anecdotes authors share moments linguistic adventures. In Milano, the early 2000’s there was no formal Yiddish teaching available, so along with her friends, Franco Bezza and Haim Burstin, Callow started a Yiddish club of three members… Though this book is about Hebrew at every turn we realize the to what extent the author values multilingualism to the point of embracing scholars who affirm: “The curse of Babel, far from being a sort of second expulsion from the Garden of Eden (the Eden of an only language) is, to the contrary, a blessing”.

In the vast literature of books about Hebrew, The language that lived twice. The Charm and Adventures of Hebrew stands out for its author’s energetic and infectious enthusiasm for teaching, as well as for the fecundity of her approach to the inner connections between language and thought.