Professor Stille graduated with a B.A. from Yale University and earned an M.S. at Columbia. He has worked as a contributor to The New York Times, La Repubblica, The New Yorker magazine, The New York Review of Books, The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, Correspondent, U.S. News & World Report, The Boston Globe, and The Toronto Globe and Mail.

He is the author of “Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families Under Fascism” (1991); “Excellent Cadavers: The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic” (1995); “The Future of the Past” (2002); and “The Sack of Rome: How a Beautiful European Country with a Fabled History and a Storied Culture Was Taken Over by a Man Named Silvio Berlusconi” (2006).

Stille is the winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Award for best work of history (1992), Premio Acqui (1992), San Francisco Chronicle Critics Choice Award (1995), and the Alicia Patterson Foundation award for journalism (1996).

During the past fifty years, most of the debate on the Catholic Church’s relationship with fascism has focused on the wartime period and the Vatican’s response to the Holocaust. Did the virtual silence of Pius XII, who became pope in early 1939, about the mistreatment and extermination of Europe’s Jews facilitate Hitler’s Final Solution, as his critics insist, or was it, as Pius’s defenders maintain, a heroic act of self-discipline that prevented Nazi reprisals against the many thousands of Catholic institutions that were secretly hiding and helping Jews? The debate, as Pius XII inches his way toward sainthood, has become somewhat sterile since it depends partly on difficult-to-prove arguments about what might have happened had he spoken out.

One of the many virtues of David Kertzer’s The Pope and Mussolini is that it reframes the discussion by shifting attention away from World War II and looking closely at the papacy of Pius XII’s predecessor, Pius XI, who became pope in 1922, the year that Benito Mussolini came to power, and died in early 1939, several months before Hitler invaded Poland. Taking advantage of the gradual opening of Vatican archives, Kertzer offers us a much more detailed portrait of the inner workings of the Vatican in this period. The many revelatory incidents, documents, and scenes he adds to the story are bound to reanimate the older debate on Pius XII.

When Mussolini seized power in his so-called March on Rome in October 1922, Achille Ratti, a scholarly librarian and former archbishop of Milan, had only recently become Pope Pius XI. The Catholic Church had not been particularly supportive of fascism during its rise. Mussolini, after all, had started out his career as an outspoken atheist and anticlerical firebrand. The Church supported its own specifically Catholic party, the Partito Popolare, or Popular Party, which competed with both the Socialists and the Fascists.

To the pope’s surprise, on taking power Mussolini immediately began a concerted campaign to win the Church’s support. He used his first speech to Parliament to articulate his vision of a Fascist society that placed the Church at the center of Italian life: the Fascist Party would be the unquestioned authority in political life and the Church would be restored to its primacy over the spiritual life of the nation. Mussolini followed up his speech with a series of concrete actions: crucifixes were placed in every public school classroom, courtroom, and hospital room; insulting a priest or disparaging the Catholic religion was made a criminal offense; Catholicism became a required subject in public schools; and considerable state funds were spent on priests’ salaries, as well as Church-run schools overseas.

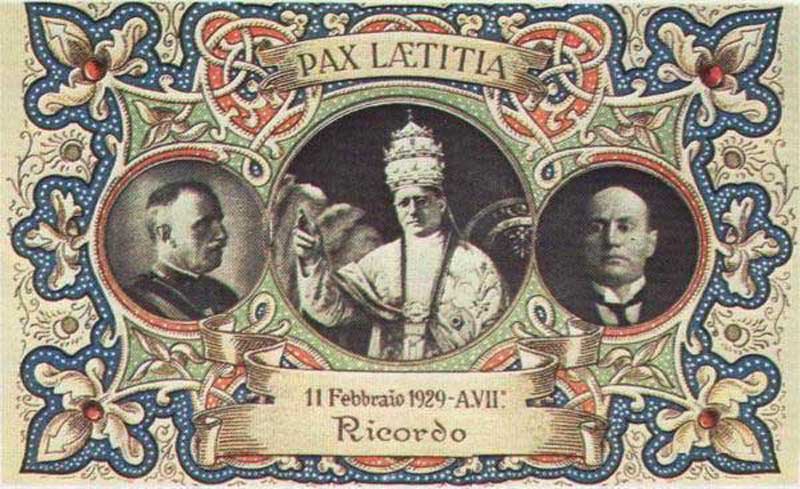

This represented a remarkable departure—not just for Mussolini but for Italy. The battle to create a united Italian state had been fought, in part, at the expense of Church power, and resulted in the end of the pope’s temporal rule over Rome and much of central Italy. It took the popes decades to realize that Italy was a permanent reality that they needed to accept. Mussolini offered them the possibility of doing so on highly favorable terms. Almost immediately he began secret negotiations for a treaty between the Vatican and the Italian state. This concordat, known as the Lateran Treaty, was signed in 1929; it made Catholicism Italy’s state religion and compensated the Church for its lost territories with a generous financial settlement. Pius XI was so pleased with the treaty that he referred to Mussolini as the “man sent by providence.”

The general outlines of this story have always been matters of public record, but Kertzer’s book deepens and alters our understanding considerably. The portrait that emerges from it suggests a much more organic and symbiotic relationship between the Church and fascism. Rather than seeing the Church as having passively accepted fascism as a fait accompli, Kertzer sees it as having provided fundamental support to Mussolini in his consolidation of power and the establishment of dictatorship in Italy.