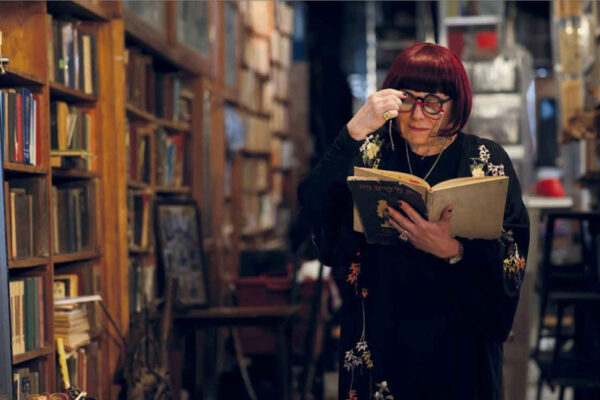

Fabrizio Lelli in conversation with Alessandro Cassin

The last Jews left Apulia in 1541. In 2001 Fabrizio Lelli arrived at the University of Lecce to teach Hebrew language and literature, in a city with no Jewish population. This year, from Sept. 6th through the 10th, Apulia will mount the NEGBA, a Festival of Jewish Culture.

Professor Lelli is ideally suited to help us navigate these prima facie contradictions. He trained in Florence and Venice, and later at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, University of Pennsylvania, and UCLA: “My field is Tuscan Jewry, particularly during the Renaissance, a period when the Jews had all but disappeared from Apulia”. This did not discourage him from launching in Lecce one of the few Italian academic programs of Jewish studies, where Hebrew language and literature are taught along with history of Judaism. The same department also offers courses in medieval and modern Jewish History as well as contemporary US history with a particular emphasis on the relationship with Israel.

The Festival of Jewish Culture, named NEGBA – meaning “towards the South” is organized by the Unione delle Comunità Ebraiche Italiane and Regione Puglia – Assessorato al Mediterraneo ed Attività Culturali in collaboration with local administrations. The idea is to provide a symbolic fusion of historical traditions and provide dialogues among the different cultures that have inhabited these areas. The Jewish tradition will emerge through concerts, theatrical performances, exhibits and talks, as part of the cultural patrimony of this region. From Trani the Festival will travel to six other cities.

Trani will celebrate the 10th edition of the Giornata Europea della Cultura Ebraica on September 6th and then in a joint venture with the Regione Puglia, NEGBA the festival will move its programs to Bari, Oria, Otranto, San Nicandro Garganico, Andria and Lecce, in other words touching on all the major places were Jewish life once thrived in Puglia.

AC: From this side of the Atlantic, the mention of Italian Jews evokes images of the communities that flourished in towns and cities of the Center/North, but for centuries Jews inhabited the South as well. How would you to explain the multifaceted relationship between Judaism and Apulia starting from this Festival?

FL: This year’s festival begins in Trani, which has a unique history. The Jewish community, which had disappeared … has been re- established. Around 2002-2003 a small group of local Christian converts obtained the restitution of a former synagogue. During the centuries the building had been transformed into a church which became a property of the Trani municipality around the end of the nineteenth century. Once they got the use of the former synagogue, the group started proceedings with the Unione Delle Comunità Israelitiche Italiane to be recognized as an autonomous Jewish community. They have not quite secured that status yet, but they are on their way… An unprecedented case.

AC: How many members does this new community have and who are they?

FL: Around 35 members. As you know, Jews do not practice any kind of proselytism. These people claim to be returning to the faith of their forefathers, they believe to be descendants of the Marranos and other Jews who were forced to convert.

AC: Is there merit to these claims?

FL: My students and I have researched very thoroughly the existing documents, but the Marrano tradition, being a secret one, naturally left few traces, so it is very hard to substantiate these claims. There is however a strong and pervasive spiritual quest in these areas, which often does not find an answer in Christianity and looks to other traditions. There are a number of conversions to Islam as well.

AC: Did the present day Jews of Trani go through a full conversion process?

FL: Yes, and though I cannot give you the religious details, I know that they have been assisted and followed in their journey by the rabbinate in Rome.

AC: Do you think it is possible today, or will it be possible in the future, to establish with any degree of certainty how many people can claim to descend from the converted Jews living here in the 1500’s?

FL: I seriously doubt we can come up even with a rough number. The Marranos had strictly clandestine traditions, which leaves us with two alternatives: in the absence of documents we cannot state as fact that any individual is a descendant from that tradition or, as the Tranesi believe, we can give credit to oral testimonies passed down from generations which hint at people practicing Jewish rituals disguised as Christian ones. There are claims that old women would fervently participate in some aspect of Christian holidays, while secretly thinking about and mentally reliving Jewish festivities.

As a historian I am fascinated by these oral traditions, yet I am somewhat skeptical. Unlike in Spain and Portugal were the brutality of the Inquisition was a lasting deterrent, I would guess that here 100 years after the expulsion of the Jews, someone would have recorded something in writing.

AC: To what period can we attribute the first vestiges of Jewish life in Apulia?

FL: The first Jews to settle in Western Europe were the Jews of Apulia. Archeological findings confirm the oral tradition that tells us that after the destruction of the Temple, emperor Titus brought back some 8000 Jews who settled in Apulia and started the first Diaspora. Some settled here, others spread throughout Italy, and eventually all over Europe.

AC: There is an uncanny symmetry between the 8000 Jews that Titus brought to Italy from Palestine and the 8000 who were deported from Italy during the Shoah.

FL: I see Apulia as both a point of arrival and departure in the migration flux of Jewish history. For those Jews captured by the Romans, the port of Brindisi was an ideal way of keeping a connection with Palestine. Being the easternmost point of the Southern Italian ports, it was also a hub of communication with the Eastern Mediterranean which in later years welcomed many Jewish communities. Many centuries later, in the 1930’s- 40’s, Jewish refugees who looked to Palestine as a hope fore a new life, took the reverse route, departing from Brindisi this time towards Palestine… In a kind of a conclusion of a very long historical cycle, Apulia and Palestine, or what was becoming Israel, were being linked through a naval voyage across the Mediterranean.- Or to phrase it differently: the European Diaspora began in Apulia, in Salento, and a part of the European Diaspora ended in Apulia.This centrality is historically undeniable, though of course not all Jews came here nor departed from here.

AC: What happened in the 1930’s in the town of San Nicandro is really a story within the story of Apulian Jews.

Around the time that Mussolini started his policy of official anti-Semitism, a community of peasants from the town of San Nicandro, inspired by a man called Donato Manduzio, -though they had never had any contact with Jews-proclaimed themselves Jews and began to observe the commandments of the Torah, and eventually migrated to Israel.

AC: Other than the classic study, San Nicandro, Histoire d’une Conversion by Elena Cassin, 1957, have there been recent findings?

FL: That book remains the main source on this topic. Recently Francesco Lotoro, a talented musician and musicologist who is also one of the members of the new Jewish Community of Trani, has released a collection of songs from the Jews of San Nicandro: Fonte di ogni bene- Canti di risveglio ebraico composti dal 1930 al 1945 a Sannicandro Garganico. And there have been articles as well as a few contributions from local erudites on this topic.

AC: Why aren’t more people investigating such a unique story?

FL: As far as new historical or anthropological research it is hard because the population migrated to Israel and is dying out. Also one would need a knowledge of Hebrew, Italian and Pugliese dialect, along with specific historical, religious and anthropological skills… not easy to put together.

AC: There are striking similarities between the landscapes of Apulia and Israel.

FL: Absolutely. And this could be why Jews in early times felt at home here; the coloring is similar, the stones, the climate, the sea.

AC: What is unique about the study center at the University of Lecce?

FL: Lecce is one of the few places in Italy where we were able to put together within the same department the study of Hebrew literature and language, as well as a program of Jewish studies. When I arrived, my area of expertise was Renaissance Jewry, particularly in Tuscany. The last Jews left the Apulian area of Salento in 1541, but really Judaism stopped being a culturally relevant force in the region by the end of 1400’s.

AC: Where did your research began in Apulia?

FL: My first challenge was, along with my students, to try and trace where the Jews migrated to – when they left Apulia… One must keep in mind that by 1400 the Jews in this area were not the descendants of the first Jewish settlers, but rather Jews who had come here later from various places. Some had arrived from Northern Italy, many of them crossed the Adriatic before and after the fall of Byzantium, but the majority had come from Spain. After the 1500’s as the Jews left Apulia, they tended to follow the routes of Sephardic Jews (in flight from Spain and Sicily) and move east toward the Ottoman Empire. Some of those living on the Adriatic Coast had been in contact with the Venetian Republic. The wealthier ones moved to Venice or to the Venetian Islands. Corfu was another favorite destination because of its geographical closeness to Apulia and its close ties to Venice.

AC: Do you think that the exit of the Jews in the early 1500’s further damaged the already impoverished economy of the region?

FL: Not really, or not in noticeable ways. By then the area was severely depressed, the wealthier Jews, merchants and moneylenders had mostly left on their own. Those who were forced to convert or leave were generally the poorest Jews.

AC: Before they left, Jews in Southern Italy enjoyed a wider variety of trades and professions than in the North.

FL: In the North, depending on necessity, Jews were called to fulfill roles that were forbidden to Christians, or in which they had specific skills. In the South, since Roman times they were allowed to engage in practically all activities, though they has a distinct predilection for the trading and dying of cloth, particularly silk.

AC: Do you feel there is still much to discover in terms of documents, manuscripts, etc.?

FL: Within what has already been discovered and largely catalogued,(mostly medieval sources) there are probably few surprises. Many of the archives have been destroyed by fires, flood, bombings and earthquakes. Scholars have pretty much searched all the likeliest places.

AC: What are more promising areas of study?

FL: I am fascinated by tracing through manuscripts the movements and linguistic transformations of the Jews of Apulia. For instance trying to figure out who were the local scribes who copied the manuscripts and then looking for similar ones in places like Corfu, Salonika, Istanbul, where we know the Apulians went…. I have attempted to follow these itineraries. The main difficulty lies the fact that in later centuries, coming into contact with Spanish and Ladino speaking Sephardim, the Apulians lost most of their linguistic and cultural specificity.

AC: You are about to publish a collection of studies on Salento.

FL: It will be ready by the end of the year and it will include contributions by linguists from Jerusalem, who have studied how in the Corfu Hebrew, one can track linguistic elements that come from Apulian dialect… Which is also a useful tool to establish the type of Hebrew spoken in Apulia in 1400’s. (Gli ebrei nel Salento, edited by di F. Lelli, which will contain essays by 18 international authors on topics of language, literary production, liturgy, manuscripts and arts of the Salento Jews from the 9th to the 16th Centuries.)

AC: What other projects are you working on?

FL: We are now working on a rather specialized project: a glossary of interference between the various Italian dialects and Hebrew (www.casvi.sns.it). The preliminary results are promising. Another area that I am exploring is that of tracking the Jewish refugees who were stationed or passed through Apulia during World War II. These people left many traces, written documents, letters etc. that are just now being sorted and translated, We have created a website, together with Regione Puglia, which will be absorbed by my University Department: www.profughiebreinpuglia.it. As the survivors enter their last years, we’d like to collect the firsthand testimonies of the tens of thousand of Jewish refugees who were interned in camps between 1940-44, on their way to Palestine and to America. Contributions to this website are by my students and others in both Israel and the USA, including the Shoah Foundation at the University of Southern California in L.A.

AC: Are you also involved in the rediscovery of the Apulian Jewish liturgy?

FL: Yes, and this could be of particular interest to the new community in Trani, having to choose a specific rite, might want to go back to the Apulian Jewish liturgy, which has been lost since the beginning of 1500’s.

AC: What can be done to make this rich history known to a wider public?

FL: The first thing is to teach it to the local population starting with the public schools. Kids are sent to visit concentration camps in Poland, but are never told about the transit camps for Jewish refugees right here in Apulia. By simply talking to their grandparents children could find out a wealth of fascinating information. I think the teaching should start locally.

AC: You teach in a department of modern languages; who are your students and what attracts them to Hebrew?

FL: Naturally the main area of interest is Israel and Israeli literature. As you know Israeli contemporary literature is very popular in Italy. The students are drawn to a world that seems very remote, yet close. Some are interested in journalism and are looking for critical instruments for a better understanding of the Middle East.

AC: What are the visible traces of Jewish heritage for the general visiting public?

FL: In Trani the two main synagogues are still standing. On September 6th the Museum of Apulian Jewry will be inaugurated in what was formerly the major synagogue of Trani. Venosa, which is not geographically in Apulia but was inhabited by Apulian Jews, has recently reopened very interesting medieval Jewish catacombs; there are also archeological findings in Bari. In Salento, on the site of the World War II refugee transit camps, the Museum of Remembrance was inaugurated in January. The highlights are a series of mural painting by a Romanian Jewish artist and of course several Giudecche (the ruins of the living quarters of Medieval Jewish communities).

AC: The Regione Puglia together with the Rico Semeraro Foundation (Lecce), of which you are the scientific coordinator have produced a number of DVD’s.

FL: The first DVD was completed in 2007 and is about the former refugees from the transit camps in Salento, who now live in Israel.

Another one in the making (ready in the fall) is about the refugees from Darfur who have reached Israel. Both are the result of a fruitful cooperation with the Ofek School for Gifted Children in Jerusalem; a third one (also work in progress) will be about former refugees from the transit camps in Salento, who now live in the USA.

AC: What aspect of your program at the University of Lecce could help promote cultural tourism in Apulia with particular attention to the Jewish heritage?

FL: The teaching of languages like English and Hebrew can be a valuable instrument in the formation of young people specialized in giving informed tours of this areas to Jews coming to visit from all over the world.

To appreciate this history and culture, the visitors must start from an understanding of the territory, the towns, cities, landscapes, coastline. Apulia was a crossroads of many culture. Rediscovering the Jewish past is a first step to understanding a complex multicultural history that has a lot to teach us about our past and our future.