History as Memory: Conversation with Sergio Parussa by Alessandro Cassin

Parussa invites the reader to consider the writer as a witness who salvages the past from silence and oblivion, defining memory as essential for our relationship to both present and future.

Though an academic work with a strong theoretical framework,Parussa’s book is written with great clarity and passion. This is a highly successful attempt to appeal to a wider non-specialized audience. The book is situated in the fertile territory between cultural history and literary criticism.

Though an academic work with a strong theoretical framework,Parussa’s book is written with great clarity and passion. This is a highly successful attempt to appeal to a wider non-specialized audience. The book is situated in the fertile territory between cultural history and literary criticism.

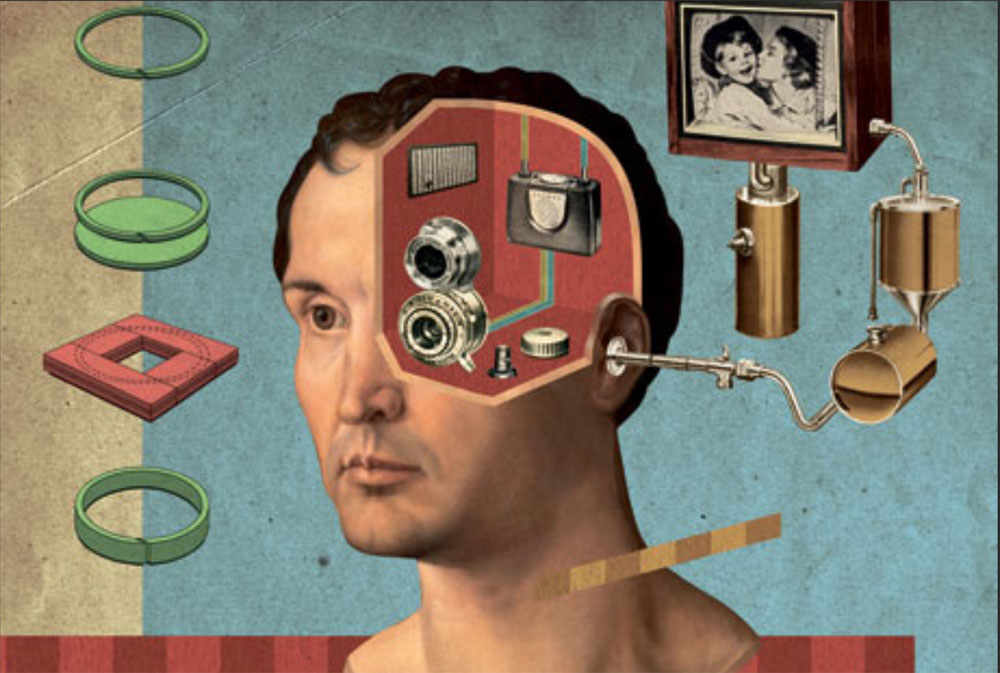

AC: You begin your book with a detailed description of Tate Thames Dig, a 1999 work of art by contemporary American artist Mark Dion. A double-sided cabinet that contains artifacts retrieved from the banks of the Thames River, The Tate Thames Dig is an installation which combines elements of late-nineteenth-century archeology, detection, and taxonomy, emulating their impulse to collect, classify, and preserve material fragments of the past as tangible proofs of an idea of history as progress. However, you argue that in Dion’s project all the principles and conventions of late-nineteenth-century scientific disciplines are inverted to reveal a more personal idea of history as memory. This idea becomes a central metaphor for your book.

SP: I spent my sabbatical year at the Center for Hebrew and Jewish Studies in Oxford. I was looking for an image, a metaphor, or a symbol that would function as a thread connecting the different parts of my book and would allow me to make a coherent discourse on Judaism and writing in contemporary Italian culture. When I had almost finished writing my book, I stumbled onto Mark Dion’s installation at Tate Modern in London one day. It is a large wooden cabinet in the style of nineteenth-century display furniture that can be found in museums of science and natural history. Over the course of several years, Dion and a team of volunteers had combed the foreshores of the Thames River and collected a wide variety of objects left behind at low tide: whole and broken glass, precious artifacts, cheap pottery, ancient fossils, and plastic bottle caps. All of these fragments were cleaned, classified, and arranged by color, type and name in the wooden cabinet.

Upon approach, Dion’s piece forces viewers into a role different from that of observer only. One realizes that the  cabinet doors can be opened, drawers can be pulled out and behind those doors, inside those drawers, there is a wide collection of objects that one can explore. Active engagement is invited. The viewers may try to mentally reassemble those fragmentary objects, think of the people who handled them, and realize that the cabinet was never simply meant as a museum showcase, but as a repository of loss. In this perspective, the gaze of the viewer is no longer the gaze of a nineteenth century scientist; rather it resembles the backward gaze of the witness who revisits the past in the hope of saving it from oblivion, changing the perception of the present, and finding a possibility for the future. The artist’s and the viewer’s gestures both evoke a repetition of the act of remembering.

cabinet doors can be opened, drawers can be pulled out and behind those doors, inside those drawers, there is a wide collection of objects that one can explore. Active engagement is invited. The viewers may try to mentally reassemble those fragmentary objects, think of the people who handled them, and realize that the cabinet was never simply meant as a museum showcase, but as a repository of loss. In this perspective, the gaze of the viewer is no longer the gaze of a nineteenth century scientist; rather it resembles the backward gaze of the witness who revisits the past in the hope of saving it from oblivion, changing the perception of the present, and finding a possibility for the future. The artist’s and the viewer’s gestures both evoke a repetition of the act of remembering.

I found this artwork profoundly moving. I felt that it could become, metaphorically speaking, the thread that I needed for my book. The piece seemed to represent very accurately what I was writing about. My encounter with that work of art, which I understand to be about the working of memory, was a turning point in the writing of my book.

With this reference to Dion’s installation, I also wanted to emphasize my interpretation of the notion of memory in Jewish tradition as a subjective attempt to collect fragments from the past and make them significant in the present. In this way, each time we look at those fragments, they look different. A similar process happens in psychoanalysis.

With this reference to Dion’s installation, I also wanted to emphasize my interpretation of the notion of memory in Jewish tradition as a subjective attempt to collect fragments from the past and make them significant in the present. In this way, each time we look at those fragments, they look different. A similar process happens in psychoanalysis.

AC: Parallels between the workings of memory and the practice of psychoanalysis recur throughout your text…

SP: Yes, during my stay in England, I had a chance to visit the Freud Museum in London, where Freud and his family resided after they left Vienna in 1938. That visit turned out be significant for the writing of my book. I decided then that my book would revolve around three different aspects: the possibility of retracing Jewish memory in the works of four Italian writers; writing and art as a subjective enterprise on memory (as exemplified by Mark Dion’s installation) and psychoanalysis as the patient and painful work of unearthing and interpreting lost memories for better understanding one’s present. Psychoanalysis provided me with a theoretical vantage point and a fruitful parallel to my own interpretation of memory: the collection of bits and pieces of past experience, brought subjectively together in the present. It is significant that psychoanalysis, which started in Vienna at the end of the nineteenth century, is somehow sheltered and preserved, in this small museum, in London.

AC: Looking back now is there anything else you would have liked to include in your book?

SP: I would have liked to include a fifth chapter on Elsa Morante. The way in which she deals with Jewish themes and images, her way of inscribing historical facts within subjective experience and collective history within individual memories would have suited the theoretical framework of my book. Last year, at an international symposium in Berlin dedicated to Morante’s last novel Aracoeli (1982), I presented a paper on the presence of Jewish themes and images, in particular Cabbalistic images, in her literary works. This paper could have been the point of departure for my fifth chapter, but teaching engagements, as well as my commitment to the publisher, did not allow me to complete the research in time for publication.

AC: In a sense the main thesis of your book is the possibility of reconstructing a Jewish cultural legacy in Italian literature by retracing the idea of history as memory.

SP: Yes, that is the main idea. Of course this is not the only way to approach the subject. I am simply suggesting that, since the idea of history as memory is central to Jewish thought, some of the writers I am analyzing may deal also with this notion.

AC: While making historical memories the subject of their work, these four writers set their narratives free from traditional literary genres and create new hybrid forms of literary expression.

SP: Looking at the literary text as a written artifact, I tried to analyze whether or not the inclusion of historical memories within the literary text has consequences at a formal level. In general, when writers include historical facts in literary texts, a vital tension is generated between history and imagination. One possible consequence of this tension is the emancipation of writing from highly coded literary genres. Saba’s Shortcuts, Ginzburg’s Lessico famigliare, and Levi’s The Periodic Table are literary works that were born out of a need to bear witness and take into account Jewish memories. In order to do this, these writers push the boundaries of traditional literary genres and create new modes of writing that invite us to question commonly accepted criteria of authentic literary writing. They take us back to the moment in which writing becomes literature. In this perspective, the act of writing can be interpreted both as an act of testimony and of literary freedom.

AC: The two main historical events that frame and define the history of modern European Jewry are emancipation and the Shoah. Starting with these shared reference points, the four authors exemplify a variety of approaches to Judaism within a historical and cultural tradition.

SP: Within this theoretical framework, I tried to show how the attitude of these authors towards Judaism changes over the span of a century: how it shifts from a perception of Judaism as a constraint on freedom, to a conception of Jewish identity as a tool for intellectual emancipation. At the turn of the century, among Italian intellectuals, there is a certain ambivalence toward Judaism, particularly in a writer like Umberto Saba. Later, there are various attempts to reclaim a sense of belonging to Jewish culture and heritage; in particular, I think, in the works of Giorgio Bassani and Primo Levi, and partially in those of Natalia Ginzburg.

AC: Saba remains the least known among these authors in the United States.

SP: Yes, Saba is the least known of them. This may be due to the nature of his poetry, which is unique and somehow indefinable even within the Italian poetic tradition, and therefore difficult to translate. However, Yale University Press has recently published an extensive selection of his poems in a new English translation by George Hochfield and Leonard Nathan (www.thenation.com/doc/20090406/stewart ). This will certainly help to make Saba’s poetry available to a wider audience in America.

AC: The other three writers you deal with in your book are more familiar to American readers.

SP: Primo Levi, of course, is widely read in America (W.W. Norton is planning to publish his complete works in 2010); Giorgio Bassani is known mostly for the film adaptation of his novel The Garden of the Finzi-Continis. Natalia Ginzburg is known especially for her 1963 family memoir Lessico famigliare, translated in English as The Things We Used to Say.

AC: For the four writers you selected, Mussolini’s anti-Jewish legislation and later Nazi-Fascist persecution, defined them as Jews in ways tragically specific to that generation. You quote Natalia Ginzburg as saying, “My Jewish identity became very important to me from the moment the Jews began to be persecuted. At that point I became aware of myself as a Jew… So, while I did not have any sort of formal Jewish upbringing, I nevertheless felt my Jewishness very acutely during the war years.” Do you think was this true for all of them?

SP: Yes, but only to a certain extent. Adverse historical circumstances helped these writers to recover their sense of Jewish Identity. However, I describe this paradox as an active response to persecution. None of these writers was religious, yet all of them recovered, or strengthened their sense of belonging to Jewish identity, not simply as a passive acceptance of an identity imposed from the outside by anti-Semitism, Fascist legislation, and the Shoah,

but as an active response to persecution. By reconnecting with centuries of Jewish life that preceded and followed the Shoah, these writers revive an idea of Judaism that includes the Shoah but is not exclusively identified with it. As noted by James E.Young, this meaningful connection with the past is a way to oppose Hitler’s design to destroy the possibility of regeneration through memory that has characterized Judaism throughout the centuries. The survival of this practice of memory is also the survival of Judaism.

AC: Can you give an example of this?

SP: There is a proud response to persecution in Primo Levi’s Zinc, the chapter of The Periodic Table where he draws a comparison between himself as a Jew and a mustard seed. As a Jew, he writes, I’m the mustard seed, the impurity that does not really mingle with mainstream society, but that is necessary for the soil to be fertile, the wheel to turn, life to be lived. I find Levi’s polemical reference to the Christian parable of the mustard seed very significant, not only because it allows him to state the importance of cultural and religious difference, but also because, through this polemical reference, Levi regains possession of his sense of belonging to Judaism that would otherwise be imposed only by the external gaze of the persecutor.

AC: Levi’s texts are full of quotations from the Bible and other Jewish sources, but they are always re-contextualized within his own discourse.

SP: Precisely, and his own discourse is never just a religious discourse, but something larger. Levi was a secular intellectual, but in many of his texts he gives voice to ethical themes that border on a spiritual sense of hope and expectation. The best-known example of this is his rewriting of the Shemà, in which the Jewish prayer of faith in the unity of God becomes a powerful call not to forget Auschwitz, a secular prayer against dehumanization.

AC: You quote from Saba’s correspondence as he muses on the poet as child. “To create, one thing is necessary above all: that somewhere our childhood must be preserved. The poet is a child who having reached adulthood, marvels at the things that happened to him.” Do you think his image of the artist as a child can serve as metaphor for the relationship between memory and creativity in general?

SP: I think it is a metaphor for the relationship between memory and creativity in Saba. In his theoretical writings, Saba often muses on the notion of a substantial opposition between poetry as the art of childhood, sensuality, and imagination, and prose as the art of old age, ethical meditation, and historical remembrance. In my interpretation, this opposition between childhood and maturity, poetry and prose, reflects another deeper opposition that haunted Saba’s life from his childhood: that between, on the one hand, the seriousness and the pessimism that he perceived as deriving from Jewish culture, and from his Jewish mother, and, on the other, the lightness and joy of artistic creation that he often associated with Greek culture and with his Catholic father. In these oppositions, one can hear a distinct echo of the collective ghosts and fantasies that would haunt European culture and nurture European anti-Semitism during the twentieth century. Saba tried to overcome these oppositions through his writing, but I don’t think he ever gets over them completely. I like to think that Ernesto, Saba’s last work inspired by the poet’s own childhood and adolescence in Trieste, is an attempt at bringing those two elements together, at reconciling his long-lasting ambivalence towards Judaism. Here, creativity is linked to memory, to remembering one’s own childhood; here, creating means, as in Freud’s psychology, finding the child within the mature man.

AC: The other writers did, however, reconcile this dichotomy, except perhaps for Ginzburg.

SP: A similar dichotomy can be found in Ginzburg’s work, in her struggle with the notion that there is a universal and a particular way of writing. In an interview, she talked about her desire to elude the particulars of her own life (her having being born in a provincial city, as well as the Jewish origins of part of her family) in order to have a panoramic glance on all aspects of the human experience. She often contrasted her own work to that of Elsa Morante, whom she felt possessed the panoramic view of things, namely the narrative skills to tell stories of universal value.

AC: Morante and Ginzburg were in fact two opposite characters in the larger context of Italian literature.

SP: Yes, they admired each other’s work very much, but were very different writers. My reading of Ginzburg, however, focuses more on her struggle between fiction and history, imagination and reality, or, as she herself writes in an essay, between “playing with domestic kittens and taking wild tigers out for a walk.” I suggest that, when Ginzburg confronts the tigers, when she includes historical memories in her works, in particular Jewish historical memories, her way of writing changes: she abandons her desire to write a very abstract, universal story in favor of writing a very concrete, particular one; and, paradoxically, this is the moment she finds her universal voice. Of course, I am thinking of her memoir Lessico famigliare in which she shifts from writing a very abstract story to writing the very particular story of a specific Italian family during the first half of the twentieth century.

AC The more specific her focus, the more universal the reach…

SP: I think this is another aspect of Jewish narrative traditions from Biblical times. As Erich Auerbach notes in his famous essay Mimesis, Biblical narratives are characterized by a level of historical and psychological depth that is lacking in Homeric narratives. In comparison to the fixed and abstract nature of Homeric heroes, who remain the same from the beginning to the end of their lives, characters in the Bible show a certain degree of psychological development. Unlike Homeric legends, biblical stories do not present themselves as distant and abstract paradigms of human behavior but as narratives that preserve the particular mutability, the confusion, and the contradictions of history. It is precisely because of this particularity and historical concreteness that biblical stories and characters are closer to us and can assume universal meanings. I think that, until the publication of Lessico famigliare, Ginzburg seeks the universal character of her stories by writing narratives of an abstract and indefinite character. However, when she sets out to write Lessico famigliare, when she decides to write the story of her family — a particular story, in a specific town, in a given moment of history — she becomes able to tell a universal story and thus resolves the impasse between memory and invention.

AC: Being in touch with an active cultural memory is one of the prerequisites of another large topic you explore: freedom…

SP Freedom and memory are strictly connected. One becomes free also by remembering one’s own particular, different history and by realizing what this history means in the perspective of time. As the French philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch writes, in Judaism there is an en plus. It is an additional meaning, something that cannot be precisely defined, and doesn’t depend on religion, race, or nationality, but on an arrière-fond, a depth which is both historical and eschatological. On the one hand, there are the remains of an ancient history and, on the other, there is the displacement of the meanings of that history towards the horizon of time. From this perspective, freedom becomes both as responsibility toward the past and an openness toward the future.

AC: Jankelevitch also states that Jewish history is characterized by the tension between two contradictory aspects: the tendency to integrate, and a desire to maintain a religious and cultural difference. Your discussion of four Italian Jewish writers is in effect a study in how they each deal with this duality in their writing. Can you give some examples?

SP: According to Jankélévitch, this tension and contradiction exist in everyone and represent one of the most profound human freedoms: the freedom to be, at the same time, equal and different, oneself and something other than oneself. Difference, any difference, says to the individual, “I’m here anyway.” And this is precisely the freedom that the anti-Semite denies to the Jew: the possibility not only of being Jewish, but also other than Jewish, of being at the same time equal and different.

I think this tension remains very problematic in Saba because, like many other Italians at the turn of the century, he had internalized anti-Semitic propaganda. In his work, the possibility of being equal and different seems very remote and never fully achieved. In Natalia Ginzburg there is a certain level of uneasiness towards her mixed family origins–her father was Jewish and her mother Catholic. She often wrote of her childhood sense of non-belonging: we were  neither Jewish, nor Catholic, she writes, we were nothing. In a 1990 interview she also mentions how her uneasiness in telling stories about Jews prevented her from writing a family memoir for a long time. She also describes how she had come to understand the mixed origins of her family as a double form of belonging, as a dual citizenship. It may be significant that her family memoir, Lessico famigliare, was published in 1963, shortly after the Eichmann trial, when in Italy the Shoah started to become part of the collective historical consciousness. I think that it was not the same for Bassani and Levi who seem to have embraced more freely cultural difference as part of their identity.

neither Jewish, nor Catholic, she writes, we were nothing. In a 1990 interview she also mentions how her uneasiness in telling stories about Jews prevented her from writing a family memoir for a long time. She also describes how she had come to understand the mixed origins of her family as a double form of belonging, as a dual citizenship. It may be significant that her family memoir, Lessico famigliare, was published in 1963, shortly after the Eichmann trial, when in Italy the Shoah started to become part of the collective historical consciousness. I think that it was not the same for Bassani and Levi who seem to have embraced more freely cultural difference as part of their identity.

AC: Compared to the degree of Jewish identity of the major American Jewish writers, Italian writers appear to have a much looser sense of belonging…

SP: Certainly, and Saba and Ginzburg were “only” half Jewish. Of course the mixed family origins with their own specific dynamics may explain in part the complexity of the issue.

AC: Ginzburg and Saba also represent the large number of European Jewish writers of the first half of the twentieth century who had one Christian parent.

SP: Marcel Proust is in the same group. Many of them had ambivalence and conflicting feelings toward their own sense of belonging.

AC: Natalia Ginzburg, Giorgio Bassani, and Primo Levi were primarily novelists, Umberto Saba was primarily a poet. Yet, after World War II and his experience hiding from Nazi-Fascist persecution and later in his dealings with psychoanalysis, he showed a renewed interest in prose. You write that, from World War II until the end of his life, his writing begins to “privilege memory over imagination and meditation over experience.” How do you explain his passage from poetry to prose and some hybrid forms of writing?

SP: Toward the end of his life, Saba said that there was no poetry left in him, whereas he felt there were still many short stories that he could write. As I said before, he liked to think that poetry was connected to the experience of the child, whereas prose was the art of old age, ethical meditation, and historical remembrance. I think that his transition from poetry to prose is connected with his dealings with psychoanalysis, as well as with a new awareness of history, in particular of the Shoah and the tragedies of World War II, and with the time that he himself had in spent in hiding from Nazi-Fascist persecution. He translated all these experiences in a way of writing which is no longer poetry, but a kind of short prose, aphoristic and meditative. I perceive this shift as closely connected to an awareness of the tragic history of Jews in the twentieth century. Shortcut — Saba wrote referring to a volume of aphorisms and brief prose compositions he published in 1946 — is born out of a response to Majdanek.

AC: For Bassani remembering is not simply narrating Jewish histories…

SP: Bassani’s works can be interpreted as an attempt to preserve Jewish memories, not simply because they recount Jewish stories but because they share a way of remembering the past that is central to Judaism: memory as an attempt to salvage the past and to change the present. One of the elements that characterizes Bassani’s novels is a nostalgic gaze towards the past. As an example, one can think of all the old, forgotten objects that are scattered throughout Bassani’s novel The Garden of the Finzi-Continis. These objects are often surrounded by a nostalgic aura. Perhaps you will remember the description of the various objects in the Finzi-Continis’ villa that represent the family’s emancipation from the ghetto, and are unequivocal signs of their conquest of freedom. Conversely, you might recall the collection of lattimi in Micòl FInzi-Continis’ room: cups, flasks, bits of glasses of every kind that could have become precious Venetian glasses but that were instead thrown out and forgotten: objects that hint at Micòl’s opaque future, as well as at the tragic future of many European Jews. All these objects seem to be obsolete and destined to disappear. However, in Bassani’s work, they are not so much the emblems of a nostalgic pilgrimage to the dear, lost places of one’s own past, as the signs of an ethical journey that tries to bring the past back to life.

AC: In what ways do you find Bassani’s work relevant today?

SP: I think that the density with which he brings together local and universal history deserves further attention. Most of his novels and short stories are dedicated to the life of the Jewish community of Ferrara during the Fascist period and World War II. In his works, this microcosm takes on universal meanings that go beyond the walls of the small northern Italian city and its Jewish community. It is again an example of a narrative in which a particular becomes a universal.

Bassani is also very lucid in his descriptions of twentieth century Italian history, in particular Fascism. Unlike Germany, after World War II, Italy had no Nuremberg trial, but rather it experienced a form of collective amnesia. Bassani’s novels and short stories show very clearly that the erasure of memory continued in the post war period. This makes his works very relevant to understanding why Italy is still struggling to create a sense of shared memory of its recent past.

AC: You refer to Primo Levi’s “hybrid condition” as Italian and Jewish, as a witness, a scientist, and a humanist. How does this impact on his prose and particularly on his concept of individual and collective memory?

SP: It impacts his prose greatly because Levi writes from a very particular point of view: he writes both as a chemist and a humanist, a witness and a Jew. Also, his background is very different from the background of most Italian writers from the first half of the twentieth century. In his work, one can easily see a radical departure from the so-called prosa d’arte, the refined, highly aestheticized way of writing modeled on Gabriele D’Annunzio’s style. Since the Renaissance, Italian literature has been dominated by a strict hierarchy of literary genres. Everything that fell in between these strict categories has been considered suspicious and often labeled as non-literature. This is precisely the area in which Primo Levi found his freedom, his style, and his voice. All his works are in between autobiography and fiction, historical essay and literary work, imaginary tale and moral meditation; which is why in Italy, until very recently, Primo Levi was not considered a writer, but just a witness. His work was widely read, but it was relegated to the realm of witness writing. Of course this perception today has changed and Primo Levi’s work is considered part of the literary canon.

AC: Work, for Levi – including intellectual endeavors and writing – is the very point of human existence. Is this a specifically Jewish point of view?

SP: I don’t think it is a specifically Jewish viewpoint. I suggest the existence of possible consonances between the centrality of human work in Judaism and in Primo Levi. In his famous interview with Philip Roth, while speaking about his novel The Monkey’s Wrench, Levi insists on the importance of work: work is at the very center of man’s ethical vision. In Greek thought, creation is Cosmos, a given. In Judaism, creation is an enterprise in which humans are supposed to cooperate with the divine principle in its perfectibility. In a brief essay on the Shulchan Aruch, Levi compares the work of the scientist to that of the rabbi: both, Levi says, share the common art of making distinctions in a chaotic universe. However, one could also argue that the centrality of work in Levi’s life was simply a consequence of his being a Torinese, of coming from an environment with a very strong work ethic.

AC: Finally, in your book you make the case that all four of these writers, despite their individual differences, practiced a form of hybrid writing which sets them apart from their non-Jewish contemporaries.

SP: Yes, this hybridization is one of the elements which bring the four writers together, particularly against the background of Italian literature of their time. What I have tried to show is how their works question commonly accepted notions of universality and propose, instead, a problematic, hybrid idea of universality. Following Giorgio Agamben’s interpretation of the notion of the universal, I maintain that the imperfection of humans, their impossibility to ever fully coincide with themselves, is in fact their best claim to universality. In my interpretation, hybrid writing mirrors this existential condition, which I perceive as a strength, and potentially a powerful challenge to the literary establishment.

AC: This notion is also politically significant.

SP: Yes. Hybrid forms of writing can represent a challenge and a form of resistance to totalitarianism. Totalitarian systems do not tolerate what they perceive as different, indefinite, contradictory, hybrid. They try to turn any difference into a form of social and political inequality. In its intolerance towards contradictions and hybridism, totalitarianism manifests a desire for the resolution of every contradiction and the closing of time. As noted by Karl Popper, totalitarianism is grounded in the belief that history moves towards an immutable future, towards the Nietzschean Übermensch, the new man conceived by Fascist and Communist ideologies, or any embodiment that would overcome the limitations and imperfection of the historical human being. In Judaism, however, time is open and the future is uncertain.

AC: While doing your research, were there assumptions you had made which you had to revise or abandon?

SP: In the case of Levi I assumed that he is a secular writer, but I also found in his writing a profoundly spiritual element which deserves further investigation. The question is how spirituality can be meaningful in a secular age, even for a non-believer.

AC: Are there other areas of his work that you would like to explore further?

SP: I recently presented a paper about Primo Levi’s science fiction works. He used this literary genre in a very original way. Although he called it science fiction, the stories read like parables, with a strong prophetic element.

AC: How would you contrast the writers in your book with contemporary Jewish Italian authors?

SP: The main difference is, of course, that the new generation did not experience first-hand persecution and the war. This is a huge difference. The uneasiness that a writer like Natalia Ginzburg felt in defining her sense of belonging as both Catholic and Jewish, does not find parallels in the Italian Jewish authors writing today. A third element is that the sense of belonging to Judaism for writers of a new generation in Italy seems to be linked to an international context. I think that, to some degree, what happens in the US influences the literary discourse on Judaism in Italy and elsewhere in Europe.

AC: Israel and Israeli literature are also important…

SP: Israel is an important element that would deserve more investigation, particularly from writers of a new generation.

AC: Whom do you consider the most important Italian contemporary voices?

SP: I have not studied closely the new generation, but I think that among the Italian Jewish contemporary authors, one must consider Clara Sereni, Lia Levi, Moni Ovadia, and Elena Loewenthal.

AC: In your book, you suggest that nostalgia is not just a consequence of, but a response to persecution and loss. Can you elaborate?

SP: I like very much what Vittorio Foa once said to Natalia Ginzburg: “Nostalgia is a wonderful thing, as long as it is nostalgia for the future.” This is not just a beautiful thought, but a great way to describe a central aspect of Jewish history: the idea that the relationship to the past is a relationship open toward the future, and memory is the place in time where the past and the present can meet, where a sense of loss for the past is paradoxically turned into an anticipation of the future. The stereotypical image of the melancholic, contemplative, backward looking Jew can be reversed into a complementary image, that of the individual “who is counting the steps between him and his life,” as the writer Edmond Jabès once beautifully said

AC: Foa was speaking from a secular perspective, and yet his words touch on a central belief in Judaism.

SP: Yes, they do. Elsewhere in my book, I used another quote from Vittorio Foa. If I remember correctly, it reads: “What is old finds itself again by becoming different.” That which is lost is never really lost as long as it becomes present again in the future. This idea of an open time, in which things can be brought back, is also central in Jewish thought. What we are talking about is not archeology but a rewriting of history. I’m not saying that this is exclusively Jewish, but I’m suggesting that Judaism, in its history and thought, has interpreted this possibility and made this freedom visible to everybody else.