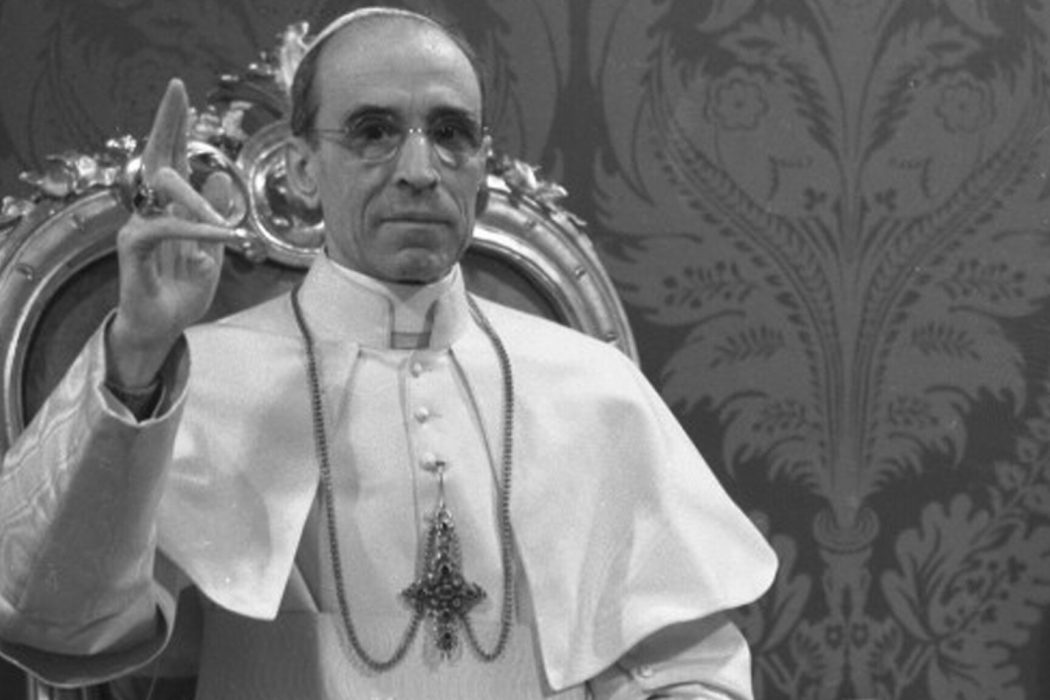

Pius XII and the 16th of October, 1943

This article appeared in the journal “Italia” edited by Robert Bonfil, The Hebrew University Magnes Press, vol. XXI, 2012. Centro Primo Levi is grateful to Prof. Bonfil for making it available to its readers.

The 16th of October 1943 will remain in the memory of Italian Jews as the tragic day on which the German SS carried out the big razzia (roundup) against the Jews of Rome, directly ‘under the windows’ of the Vatican, as Ambassador Ernst von Weizsäcker put it.

For centuries the Jews of Rome had been allowed to live in the Papal States; they were always tolerated even though they occasionally suffered from oppressive measures. Such measures included the wearing of a special badge, forced sermons, and being dragged into the House of Catechumens in preparation for forced baptism. There were also baseless accusations of ritual murder, the closure of the ghetto, and many other restrictions. Liberty and emancipation arrived hand in hand with the unification of Italy in 1870, when Italian troops entered Rome through Porta Pia and turned it into the capital of Italy.

The Jews naturally supported this process and became fervent patriots, fighting for the Italian motherland in World War One. That did not prevent Mussolini’s government from proclaiming racial laws in 1938 according to which the Jews, albeit faithful Italian citizens, were dismissed from their positions in the army, not allowed to enter ministries, no longer allowed to teach or study in public schools, and were eliminated from posts in public administration and professional life. Thousands of Jews lost years of work and were interned or forced to emigrate.

The situation of the Italian Jews deteriorated sharply after 8 September 1943, following the Nazi occupation of northern and central Italy and the laws issued by the ‘Republic of Salò’. Their citizenship was revoked and the decree issued by the Duce on 13 December 1943 imposed the internment of all Jews in concentration camps and the confiscation of all their belongings.

In this essay I wish to raise some questions about the involvement of the Vatican, and particularly of Pope Pius XII, regarding the Jews of Rome before, during, and after the fateful 16th of October 1943.

What happened to the Jews of Rome in 1943 from the 9th of September, when the Germans took control of Rome, until the 16th of October, when they mounted the raid against the Jews? The Catholic Church was the only institution present in Rome at the time which had a sovereign state at its disposal and hundreds of convents and monasteries ready to help those in need.

Pope Pius XII was aware of the dangers that German occupation of Rome could represent for the Jews. Nonetheless, the pope negotiated with the Germans on one issue only: keeping the Vatican’s neutrality and its territorial integrity, which also meant his own personal safety. The Jews’ safety was not considered an important enough issue to be of great concern to the pope. Nevertheless, hundreds of convents and Catholic religious houses in Rome did offer shelter to the Jews who came and asked for asylum.

Yet there is no evidence of an instruction from the Vatican to save Jews. One can only imagine how many more could have been saved had the Vatican issued such instructions to all its institutions. As it was, most of those nuns and clergymen who saved Jews did so of their own personal initiative.

The reasons for Pius XII’s behavior are unknown to us. We may imagine that he felt responsible for the Vatican’s own Church and State and avoided actions that could signal a sense of enmity towards the Germans. There could also be other reasons, but the real issue at stake is the moral stand of the head of the Church when facing the massacre of the Jews. To his faithful believers he was meant to be an example of morality, yet despite his power he did very little to help the Jews.

Not only did Pius XII refrain from intervening in favor of the Jewish victims, he did not even try to warn them in time to escape certain death. Pius XII failed his primary task of pointing out the road of morality. He left such an important issue to the judgment of his priests themselves. During the years following the event of 16 October 1943, the Church tried to provide some explanations, but the facts are clear.

Pius XII did not make any public declaration on this matter. We have no record even of any action to secretly inform his own priests. He was a single-track politician and above all a diplomat who tried to solve every question by diplomatic means. This is hardly possible in normal times, and even less in such an extraordinary situation as the German occupation of Europe. The Church later claimed that it did not know what was happening to the Jews, but this has been proven false.

The impression is that a major barter was implemented de facto: the territory of the Vatican would be respected and the pope would not be kidnapped by the Germans, but at the same time the Jews of Rome were to be arrested and deported. There was practically no protest by the Vatican against the deportation of the Jews.

Download full article