I love and admire Kafka because he writes in a way that is totally closed off to me. (Primo Levi)

Franz Kafka The Drawings. Edited by Andreas Kilcher. Yale University Press, 2022.

The publication of about 240 previously unknown drawings and sketches by Franz Kafka struck me like a most welcome thunderbolt. It promises to open new vistas in our understanding of one of the twentieth century’s most luminously complex, enigmatic, and elusive minds.

I was thirteen years old when I first laid my eyes on a collection of Kafka’s short stories, an experience similar to staring down into a deep well, in bewilderment. Not only do I remember the baffling kaleidoscope-like effect of his writing then, but I have continued to feel a similar sense of wonder and mystery while reading him throughout my life. My experience is surely shared by generations of Kafka’s readers. Upon each reading, the question is about Kafka’s unique ways of conjuring, in both words and drawings, such deep meditations on the human condition. Kafka’s style, prodigious imagination, unsettling angst and point-blank humor and irony, do not seem to have direct predecessors or followers. Having found only partial and provisional answers in the vast scholarship on Kafka (which includes, among many others, Marthe Robert, Saul Friedlander, Roberto Calasso and Reiner Stach exhaustive three-volume biography, I came to place him among the rare category of the poet/prophet.

Kafka is not a surface one can observe, dissect, and comprehend, but rather more of a sphere; from any angle you look at it, much of it remains in the penumbra.

The publication of a large body of Kafka’s drawings and sketches offers us a substantial entry into this so far lesser-known aspect of his oeuvre. A year after the German edition published by C. H. Beck Verlag, Franz Kafka The Drawings, edited by Andreas Kilcher in collaboration with Pavel Schmidt, is now available in English in a lavish hardcover edition from Yale University Press. The volume includes over 240 sketches and drawings, spanning from 1901 up to his death in 1924. An introductory essay by Kilcher recounts the complicated journey that brought the drawings to public attention in 2019 at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. As with his writings, Kafka had instructed his friend Max Brod to burn what he called his “scribblings” after his death. Yet as Kafka may have expected, Brod did not carry out his assignment. In March 1939, escaping the Nazi’s advance on Prague, he embarked on a ship from the Romanian port of Constanța and brought a suitcase with all of Kafka’s writings and drawings to Palestine. He later deposited the drawings in four separate safe deposit boxes at UBS in Zurich. Despite his intention to eventually publish a “Kafka portfolio”, Brod never did so and allowed only a minimal number of the drawings to be published during his lifetime. Brod had no children, and after his death, his estate was left to his assistant Ilse Ester Hoffe. Alas, Hoffe did make the drawings available, not even when Michael Kruger (from the Hanser publishing house) planned a volume of Kafka’s drawings to celebrate his100th anniversary. Difficult to comprehend personal attachments by Hoffe, and a series of legal disputes following her attempts to sell some manuscripts, delayed a resolution until Hoffe’s own death, in 2007. A decade of legal battles ensued between her heirs and the National Library of Israel, that based its claim to the papers on Brod’s will. After the District Court of Tel Aviv ruled in favor of the National Library in 2016, it took until 2019 for the District Court of Zurich to accept the Israeli legal decision. At long last, all of Kafka’s extant drawings, including those published during Brod’s life, are available at the National Library of Israel.

The “re-discovery” of Kafka’s drawings is intrinsically of great importance. Sadly, chances of new Kafka materials surfacing in the future are dismally low.

The book presents the Kafka’s visual works in chronological order: single pages and smaller folios 1901-1907; the sketchbook (undated); drawings in travel diaries 1911-1912; drawings in the letters 1909-1921; drawings in diaries and notebooks 1909-1924, and finally, manuscripts with patterns and ornaments. Each category contains compelling works, and together, they testify to Kafka’s continuous drawing and sketching practice throughout his life.

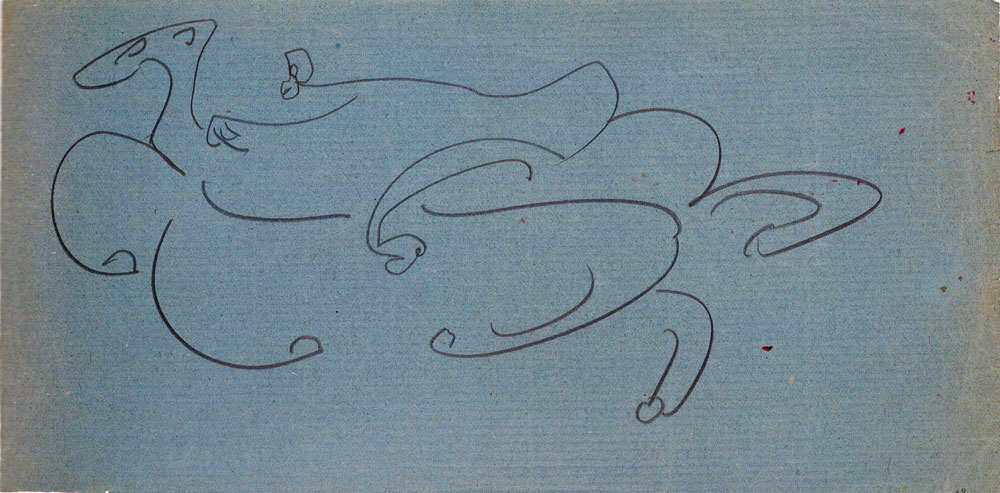

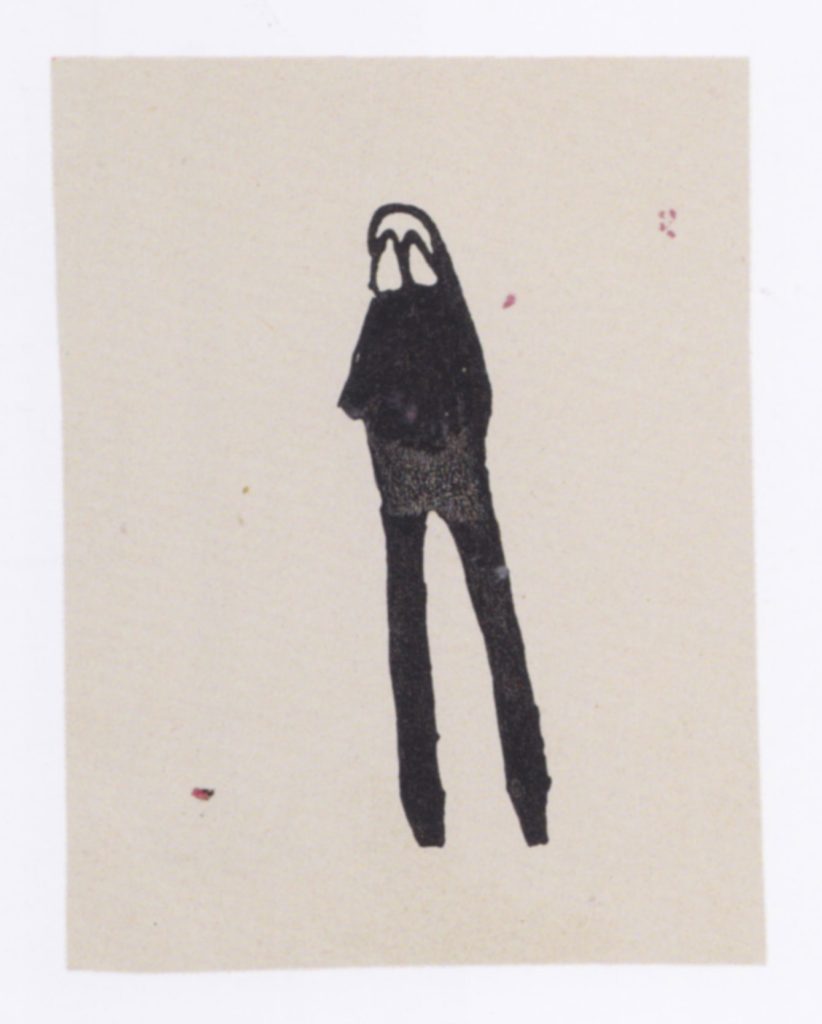

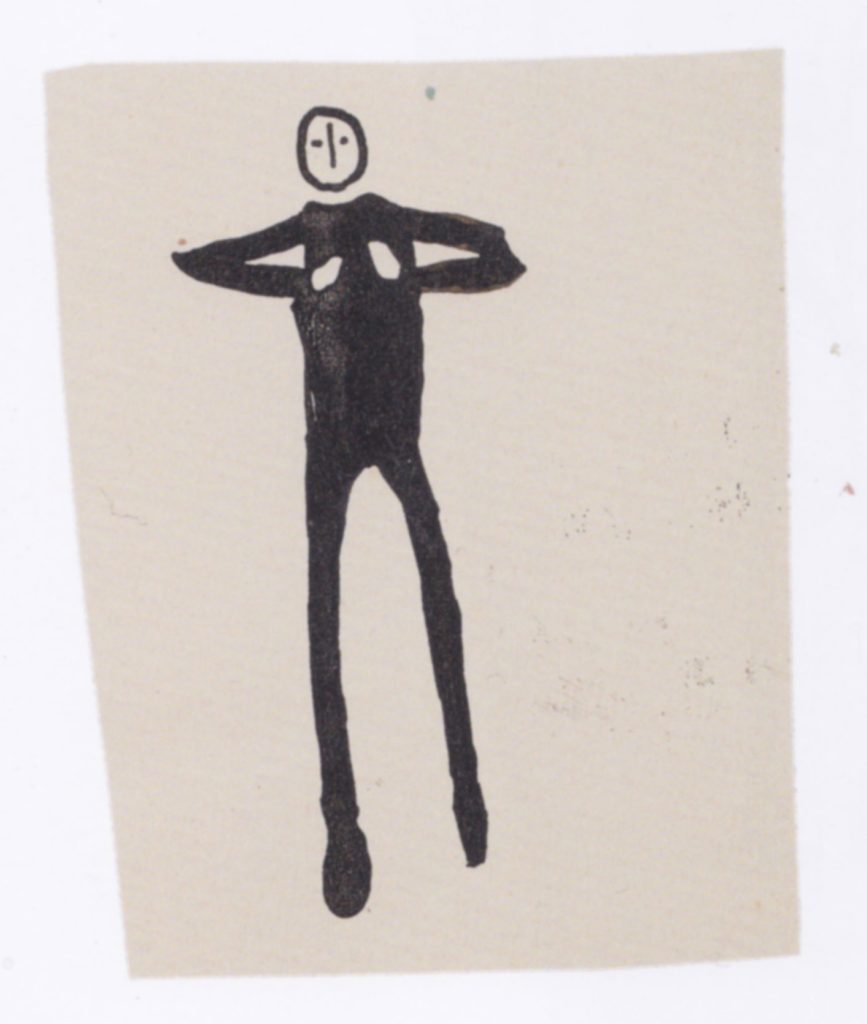

A number of these works display great visual power, aesthetic sensibility, and mystery. Yet, the point is not to attempt to evaluate Kafka as a visual artist but rather to explore the high wire, balancing act between the written word and the drawn line. Any Kafka reader will quickly realize how the drawings echo the large themes of his literary work, his use of empty space as the habitat of characters, and the reductionist essentiality and universality of his figures. The most mesmerizing realization is the parallel way in which Kafka could express himself and muse on the human condition through word and drawing. The drawings are never illustrations of the writings or their underlying ideas. As the writings stand alone, so do the drawings (or at last, the best of them), what is captivating is the relation between the two. Many other writers have produced visual works; the novelty here is finding such a well-defined literary voice possessing such a powerful visual correlative. The closest an example of this may be the work of Bruno Schulz, the Polish-Jewish artist roughly Kafka’s contemporary, who was predominantly a prose writer but whose creative output included visual works. Unlike Kafka, Schulz was trained as a painter, but very much like Kafka, his drawings augment and add depth to our entry into his prose.

Franz Kafka, The Drawings contains an essay by Andreas Kilcher which traces Kafka’s interest in visual arts (European modernism as well as”Japonisme”), the museums and shows he attended, the artists he met, the magazines he subscribed to, etc. creating both a chronology and a context for his visual works. In addition, Kilcher documents Max Brod’s repeated yet, failed attempts to establish Kafka as a visual artist. Finally, to Kafka’s contemporaries’ belief that the drawings are typically Expressionist or influenced by the Japonisme of Emil Orlik, Kilchner responds with the correct yet unsatisfactory vague assessment that “The drawings resist any attempt at a broader, more generalized classification.”

Further, Judith Butler, in her own essay, focuses on Kafka’s treatment of the human body in prose and in drawings. “Kafka’s sketches draw upon and depart from his writings. […] Even as the problem of graphic line is present in both writing and drawing, it functions very differently in each. In the drawings, it conducts a critique of what writing can do […] in the drawings the body is sketched without gravity, without ground—aloft, reduced, but also fantastical in its stretch of motion.” Finally, there is a useful catalogue raisonnè of the drawings by Pavel Schmidt.

While the drawings are the true revelation of this book, the thoughtful and informative essays outline directions of inquiry and studies that, over time, these drawings will surely elicit. Perhaps these drawings should not be approached with the eye of the art historian, nor the lens of the Kafka scholar, but rather with a willingness for wonder.

In “K.”, his literary/ philosophical inquiry into Kafka, Roberto Calasso begins by asking what are Kafka’s stories about? Are they dreams? Allegories? Symbols? After the many provisional answers scholars have offered, the mystery remains intact. Calasso proposes not to find an answer but rather to allow that the “mystery to be illuminated by the work’s own light.” Now, thanks to Andreas Kilcher and Yale University Press’s timely edition, we can ask similar questions about the drawings and further ponder on the questions foreshadowed by this book.

Cover image: Rider on blue paper, ca. 1901-1907, pencil on blue paper, National Library of Israel