After a visit to the Holocaust Memorial in Milan, New York Times op-ed contributor Roger Cohen ponders on the plight of the Syrian refugees and reminds us of how the deportation of thousands of Jews from Italy and of many more from the rest of Europe was facilitated by the fact that so many conscientious citizens looked away.

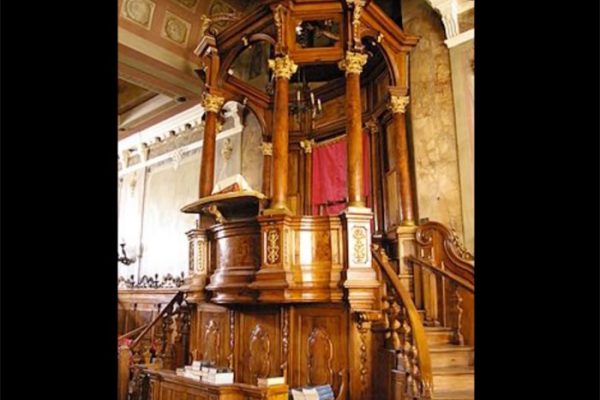

“Indifference” is the word engraved on the stark wall at the entrance to Milan’s Holocaust memorial, housed beneath the central railway station from which Jews were deported to Auschwitz and other Nazi camps. The premises vibrate when trains depart overhead, as if mirroring the shudder the place provokes.

A survivor of the deportation, Liliana Segre, whose father, Alberto, was killed at Auschwitz, suggested that “indifference” was the most appropriate word to greet visitors to the memorial, which opened in 2013. Nobody had cared when, from 1943 onward, Jews were hauled through the elegant avenues of Milan to the station. They were unloaded from trucks and packed into wooden boxcars made to transport six horses but used for some 80 doomed human beings.

So it was perhaps inevitable that when Roberto Jarach, the vice president of the memorial, was asked if he could help with Milan’s refugee crisis, he saw that word flash through his mind. As hundreds of desperate refugees converged daily on Milan’s central station — opened during the rule of the Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini — the memorial could not show “indifference.”

“I immediately came down here to measure the space we have,” Jarach told me. “These people hardly know where they are.”