This is a story of light and shadows: it belongs to one of the people whose lives have been touched by the events reconstructed in Anna Pizzuti’s book Paper Lives -Stories of Foreign Jewish Internees Under Fascism. A story that begins in San Donato Val Comino, one of the many small towns where Mussolini’s regime interned foreign Jews. It is a first hand testimony, in all its unique flavor and idiosyncratic detail, tracing the ark of a life that started in war torn Italy, continuing with an American emigration story and ending with reminiscences of its very beginnings in wartime San Donato.

It is the story of Maria Cardarelli Puzzanghero. Starting in 1940, Maria’s family, consisting in her mother and sisters Pompea and Silvana, rented the living room of their house in San Donato to the Tenenbaums – Mordko (Marco) and Ulla -foreign Jews interned in the village. Ulla gave birth to Katja baby girl, in July 1942. Forced by circumstances to live together, the two families grew to accept, love and help one another.

On April 6, 1944, when the Nazis rounded up the internees in San Donato, Maria Cardarelli Puzzanghero was a teen-ager. She saw, understood and remembers it all. While the Tenenbaums found refuge in the mountains, they left little Katja in care of the Cardarellis. They – together with their neighbor – were instrumental in getting the Tenenbaums out of town and of the Nazi’s reach in a dramatic and audacious rescue.

After the war Maria and her sister emigrated to the US where they still reside. Years later, as the Cardarelli sisters visited Italy, they contacted the Tennembaum and have remained in touch ever since.

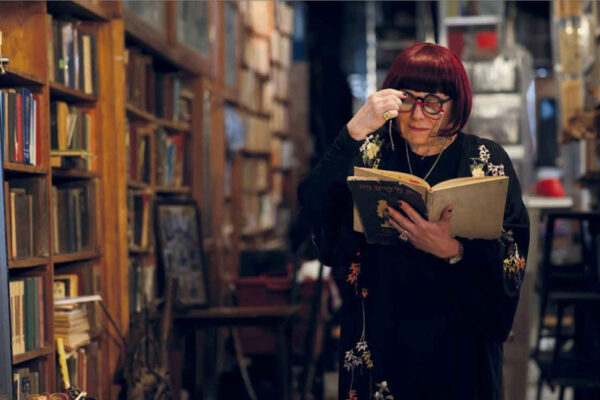

Maria Cardarelli worked as a seamstress her whole life, but after her husband’s death she found her vocation as a storyteller. One of her most emotionally charged and touching stories – one she has performed regularly over the past 10 years- is called Katja (see link to the audio clip). It contains her memories and feeling on the war period, rendered in sharp and finely narrated detail after all these years.

Alessandro Cassin: How and when did you decide to leave San Donato?

Maria Cardarelli Puzanghero: After the war, life in San Donato was bleak. We were poor and there was no work. I was twenty years old and worked as an apprentice to one of the best tailors in town, but he could hardly pay me. My father had left us in December 1930, he moved to the US and never contacted us again. It was incredibly difficult for my mother to raise us alone. After my sister Silvana got married, she, her husband and I decided to leave, in 1947.

AC: Where you looking for your father?

MCP: Yes, we were in contact with his brother who actually paid for my trip and I was convinced that our father would meet us at the ship upon arrival, but he didn’t. It was a hard lonely trip, my sister and her husband traveled in first class, I was alone in third class…

AC: Did you ever reunite with your father?

He never made himself available, I tried very hard I wrote letters (he never answered) then my uncle tried to convince him to come and see me and my sister and he said that he would. Once he made an appointment: come to South Station in Boston on such and such a day and such and such a time , and I will come with your father. My sister and I went but our father never showed up… It’s been terrible.

AC: How was your transition from a small Italian town to the US?

MCP: I had no money and did not speak a word of English: it was hard! We settled in Massachusetts, in that terrible cold winter of 1947. I began working in a dress factory: I was lucky because I had been trained as a seamstress so I already knew the trade. They immediately recognized my talent , and only a year or two later I was promoted into the designing room. I worked with a designer and a pattern maker. I made my first sample, just by looking at a sketch on paper. They paid me very well: imagine in 1950, I was making $100 a week, a lot of money in those days. I worked very hard to pay my uncle back for the trip over, and then to pay for my mother to join me, which later she did.

AC: When did things get easier?

MCP: Slowly I learned the language and the American ways. It was a struggle to adapt to a new mentality while trying to preserve my Italian identity. Meeting my husband made things easier.

AC: Tell me about your family…

MCP: My husband was an engineer. American born, but from a Sicilian family. He spoke no Italian, only Sicilian dialect which I did not understand. We had four children: two boys and two girls and now I have seven wonderful grandchildren!

AC: When and how did you become interested in story telling?

MCP: Story telling has been a revelation, though it came late in my life. I started telling stories to my grandchildren. They liked the way I told stories- children are the best judges because they tell the truth- Every time they would visit me the first question was “Rita! ( they call me Rita) do you have a new story?

That’s what got me started. Then, after my husband passed away, I started to go to story telling venues, just to listen. I remember spending a week at a national storytelling conference in Tennessee, attended by about 10.000. I discovered that there was a whole world connected to this activity. I then took workshops with storytellers and began formalizing my own stories. Soon I started attending meetings with fellow storytellers in Cambridge every Tuesday. We exchange ideas, techniques and support each other.

AC: How did you create “Katja”?

MCP: It was one of the big stories I carried with me. It took me a long time to write and to start telling it, because every time I did, I started crying. Before you can talk about something like this there is a lot of healing to do. We really saw death very close.

At one of my Tuesday meetings I announced that I had been working on it and asked to be the feature. After I told the story of Katja that first time the audience gave me a standing ovation. I was moved both by the story I was telling and by the reactions I saw in the audience. Later many came up to me and said: “Maria this is a story that needs to be told!”

AC: Where have you told this particular story?

MCP: I think I did not miss one Synagogue in the Newton area! But also in schools, libraries, museums and just about anywhere there is a story telling program.

AC: The story is beautifully conceived and scripted, do you change it every time you retell it or is it pretty much fixed?

MCP: In story telling you cannot read, so initially I memorized it. Then naturally I take some liberties, but the content and structure are always the same and the variations are minimal. I might change a few words and details here and there.

AC: What appeals most to you about story telling?

MCP: It has something ancient: the idea of people sitting around a fire, telling stories. This really creates a sense of community. If the story is spoken rather that read, it has more spontaneity and requires the teller to really know how to engage the listeners.

AC: In what ways would you say telling a personal story to strangers is different than telling it to friends or to people you know?

MCP: Of course it is different. I get much more nervous with strangers! In 2008 the University of Massachusetts in Boston, held a conference called Italy and The Holocaust, and I was invited. For that occasion I called Katja Tenembaum in Rome and asked her to come, and be on the stage with me as I told “her” story. She came and the whole event was very moving. We had an audience of about 500 people and strangely I was not nervous at all. The story just came out! At other times it has been more difficult. For example sometimes with high school students it’s hard to grab their attention, but once that happens they are present. The problem is afterwards: they invariably have lots and lots of questions!

AC: Was there one particularly memorable performance of Katja ?

MCP: A few years ago a congregation invited me to present Katja on Yom Kippur! Can you imagine, they wanted it on Yom Kippur! It was such an honor. They had arranged for me to tell the story to the youth gathered in their library. It was packed, all the eyes were fixed on me. Later I got a beautiful letter from the Rabbi, who said ”When you save one person you save a nation”. I was really touched.

AC: How long does it take you to create a new story?

MCP: It depends on the subject. Right now I am working on a story about my mother which I am calling ”The White Widow”. This is taking a lot of time since it is so emotional for me. You see, I was very close to my mother, she lived with me for many years… When you are so close to a person, you do not see their strengths and their weakness as much as you feel them, so writing about feelings is much harder than writing one’s observations. This story is proving very hard to write; I imagine it will not be ready until after the summer.

AC: What kind of woman was your mother?

MCP: She never smiled. I never saw my mother smile! Whatever happened to her, she blamed herself for some of it. The stigma of the abandonment stayed with her until she died. Even though what happened was not her fault at all. It was very hard to live with her, she was bitter. After she died I found my father’s diary from 1918, a few years before they got married. It is full of beautiful thoughts, just one love letter after the other. It seems that he was so much in love with her and she with him, that I really cannot imagine what went wrong.

AC: Do you remember the arrival of the internees to San Donato?

MCP: I was thirteen years old, our house was in the outskirts of town… My mother kept me and my sister very close to her, those were tough times… When the internees arrived, they arrived in the center of the town, by bus . We were not aloud to go in the piazza to see them but everyone was talking about them.

AC: Did you know they were Jewish?

MCP: Yes, we had been told but it did not mean much to us. There never were Jews in San Donato before.

AC: How did the Tenembaums enter your life?

MCP: One day I saw my mother rearranging living room, a large sized room, into a bed room. I asked “why are you doing this” and she said some people were going to live with us: a couple with a small baby.

AC: What were your first impressions of them?

MCP: Oh, Marco and Ulla were wonderful people! In fact I could not understand why the Government described the Jews as enemies of the country… Mussolini’s racial policies were totally incomprehensible to me. To me they were wonderful people. People like any other.

AC: How did your life change when the family moved in?

MCP: They brought a whole different culture, a higher level of conversation. They where knowledgeable and aware of many things we had had no exposure to. Marco and Ulla were charming and kind but we all loved Katja! I was the oldest sister, Silvana who was then 9 years old was the closest in age to baby Katja. Marco soon became a father figure to her.

AC: Did you interact also with other internees?

MCP: Yes I remember Misha, a veterinarian and Leon. They used to come over to talk to Marco and got friendly with us too.

AC: How would you describe the interaction between the internees and the people of San Donato?

MCP: The internees where mainly highly educated people, while the town people didn’t have much schooling. This in the eyes of my family and of many others, made them seem very interesting. They came from many different countries bringing a flair of cosmopolitanism. They knew what was going on, they talked about the war. Their experiences enriched our lives.

AC: What do you remember of every day life at home with the Tenebaums?

MCP: I can still see Marco sitting at the kitchen table by the window, studying his medical books for hours. One day, he left one of his books open on the table. I went over and saw on that particular page a picture of a naked man. My mother came over closed the book and later told him to be careful and not leave pictures like that around the house with us girls… We were also very fond of Ulla, a very intelligent woman. She helped us grow up and spoke to us about many topics like getting married, responsibility and many other topics that no one else would have explained to us.

AC: Do you remember when some of the Jews were rounded up?

MCP: Sure. As I say in my story, one morning, the sun had not made it yet over the mountains, the town and the valley were still laced in the white light of dawn, we heard the rumbling of trucks approaching the town. You must know that there were no newspapers around, we did not have television or radios. The only news that reached us were occasional papers and reports from people who passed through the town. The trucks arrived to the town stopping at different places, as if they new exactly were the Jews were living. Marco Ulla, Misha, Leon and a Yugoslav woman who was not Jewish, but interned probably for political reasons, heard the noise, guessed that something was wrong and started to run toward the mountains, like many others were doing. Other Jews, including some who lived closed by to us, could not believe that the Germans had come to harm them and simply surrendered. Clearly the fascist sympathizers had tipped the Germans off, otherwise they couldn’t have found the Jews so fast. We all saw the Jews being shoved into these trucks, saw the trucks leave the town… and never saw them again.

AC: And Katja?

MCP: In all of this she remained with us, because she was so small she couldn’t have run up the mountain. She was so little and it was so cold. That day my mother changed her name from Katja to the more Italian sounding Grazia. Some of the Germans had remained in town and we didn’t want anybody hearing us say “Katja vieni qui”. “Grazia vieni qui was safer”

AC: Was there communication between the town and the people in hiding in the mountains?

MCP: Yes, people from the town helped them with the little food the could spare, with blankets and water. Up there it was could and tough: they lived like nomads!

AC: One day Mrs. Tenembaum showed up at your door?

MCP: Yes, in broad daylight! I thought (and this is what I tell in my story) that she had come to see her daughter, but Katja learned from her that she had come to take the one valuable object they still had, a German microscope. In any case when she appeared at the door I remember my mother turning ashen color…. To reassure her Ulla said ”Signora Franceschina non mi ha visto nessuno… but she had been seen and reported to the German headquarters. About half hour later there was a knock at the door and a fascist sympathizer who also was an interpreter asked my mother for Marco Ulla and Katja… My mother said she had not seen them in months and somehow the Germans went away. As soon as she closed the door my mother fainted. It was a miracle they did not come back! I stated screaming, I thought my mother was dead . After the commotion my mother came back to her senses, and called our neighbor Costanza Rufo. Together they figured out how to get Ulla out of town before the Germans would come back to get her. That is where the idea of the basket (told in my story) was conceived. Ulla was hidden in the basket, which Costanza placed on her head and went out toward the fields while Katja dressed as a peasant girl went with my sister Silvana to our grandparents’ until the crisis was over.

AC: Eventualy the Tenembaums made it to Rome. After the war you moved to the US; when did you first see them again?

MCP: Actually Ulla helped us make the decision to move to the States. She found out that because of our paternal grandfather, we could apply for naturalization and in fact we did not have to go through Ellis Island. I went back to San Donato in 1978 with my husband. We had rented a car and as soon as we parked near our former house, all the people came out to greet me… I had not told anyone I was coming but I felt as if they were waiting for me. It was so beautiful! They said Maria you have not changed at all, of course what they weren’t looking at the physical but more at the spiritual part … The way I talked, the way I loved, and interacted with people.

AC: Clearly the Tenembaums have had a strong and positive impact on your personal life. Would you say that the collective presence of the other internees had similar impact on the town as a whole?

MCP: I cannot speak for the whole town, but certainly there were others, like Costanza Rufo, who developed strong ties with the Jewish internees. There were also some Fascist leaning people who were not happy with their presence among us.

AC: When did you reconnect with the Tenenbaums?

MCP: One year I was supposed to go back to Italy with Silvana, but I got sick and could not travel. Silvana went to San Donato and then started to look for the Tenenbaums. She found them in a phone book and called them. They got together in a very emotional encounter and we all have been in touch trough correspondence and telephone ever since. The following year I went my self and met them: such a pleasure! I later saw Katja again here in the US when she went to Harvard for some research. She came to my house and we hugged. I said “Katja, it’s a miracle to see you here in the States!” She smiled and said “No, the miracle happened in 1944.” I think the story of Katja is a story of miracles, I really believe that.