Once again Roman Jews Welcome the Pope: A surprise exhibition welcomes Benedict XVI to the Jewish Museum of Rome

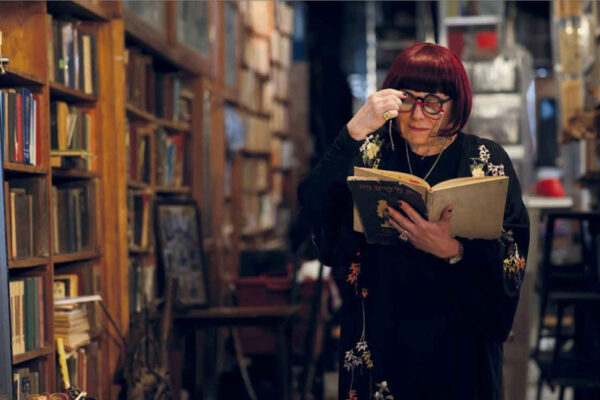

Interview with Daniela Di Castro, Director of the Jewish Museum of Rome

This is the first time that a Pope visits a Jewish Museum, thus paying tribute to the history of a community whose establishment in the capital of the Roman Empire predates by two centuries that of the Christian Church.

For the occasion, the Museum and the Jewish Historical Archive have mounted the exhibition Et ecce gaudium: Roman Jews and the ceremonies of installation of the Popes, featuring a series of 18th century panels produced by the Jewish Community of Rome for the Popes’ inaugural parades. Like many of the treasures preserved by the Jewish Community of Rome, these ephemeral decorations not only testify to the history of a minority but are also a rare example of artifacts that belong to the larger history of the city.

Centro Primo Levi interviewed Daniela Di Castro, director of the Museum and world-renowned expert in decorative arts.

CPL: What is the genesis of this exhibition?

DDC: Two years ago, during the major re-organization and cataloguing of the Historical Archive of the Jewish Community of Rome, we found a series of panels on paper, which were immediately recognized as important historical documents and were restored. Last year, thanks to a growing collaboration between the archives and the museum, we finally identified the panels as traditional ephemeral banners used in Baroque processions and parades. These particular ones were produced by the Jewish Community for the public ceremonies of installation of five popes between 1730 and 1775. When the visit of Pope Benedict XVI was agreed upon, the Chief Rabbi Riccardo Di Segni suggested we use this opportunity to show these artifacts and the history they represent. The exhibit also marks the 50th anniversary of our museum.

CPL: How do these panels compare to the ones created by other groups and guilds?

DDC: It is difficult to say. Most of these ephemeral productions were meant to last only over the course of the ceremony and they were rarely preserved. It is amazing that the Jewish community still has them. It is more than likely that all groups commissioned their panels to the same roster of craftsmen.

CPL: What is their social relevance?

DDC: First and foremost they are one of the manifestations of the fact that Roman Jews have always been citizens of Rome, under the Popes as they were during the Empire. This status was not at all common in the rest of the Western world. It guaranteed permanence in a particular territory and some degree of protection. Even during the ghetto era, and in spite of their loss of civil rights, Jews were still Roman citizens. The inclusion in the ceremonies for the Papal installation signifies their participation in public life and thus their relevance and ability to interact with other groups.

CPL: For which Popes were these panels created?

DDC: Clement XII (1730), Benedict XIV (1740), Clement XIII (1758), Clement XIV (1769), and Pius VI (1775).

CPL: How did the Jewish participation in the Papal installation change over time?

DDC: In the Middle Ages, Roman Jews used to exhibit for the new Pope and later present him with a scroll of the Torah. Through this act they defined themselves as people of the book. Some sources report of a ritual in which upon receiving it, the Pope let the Torah drop on the ground. The symbolism surrounding the law of the Torah and the legitimacy of the two religions is very present at this time. By the 14th century the Pope confirms the law but rejects any rabbinical interpretation of it. With Leone X, in 1513, the ritual of the book ends. The years following are those of the sack of Rome in 1527, the burning of the Talmud in 1553, and the installation of the Ghetto in 1555. We do not have documents concerning the participation of the Jews in the papal installation during this period.

Starting in 1590, however, the Universitas Haebreorum, as the Jewish Community was called, is again present in the inaugural horse parade that brought the new Pope across the city from San Peter to San Giovanni in Laterano. The Jews were assigned the Arch of Septimius Severus and decorated it with panels and welcoming inscriptions in Latin and Hebrew. Around the middle of the 1600 they were moved to the route that goes from the Arch of Titus (under which Roman Jews traditionally do not pass) to the Coliseum, which they were requested to decorate with tapestry and painted paper panels installed over wooden racks. Pius VI is the last Pope to be installed with the triumphal cavalcade in 1775. After him, Pius VII is elected in exile because of the Napoleonic wars. He arrives in Rome a year later and takes power with a much simpler ceremony. He eliminates the participation of guilds, associations, and the Jews from the public ceremony, and receives their gift in private.

CPL: What kind of gift?

DDC: A binder of welcoming panels. They are similar to the street decorations but are realized in a smaller scale. They are presented to the Pope who keeps them in his private library. We have identified three of such books, including those for Leo XII and Gregory XV that are included in the exhibition.

CPL: The Pope decided to move the Jews of Rome from the public to the private sphere at a time when the spirit of emancipation was already strong in the peninsula.

DDC: Yes, it is as if he tried to stop the course of history and ideas. In Rome this is also a time of repression and forced baptism. In 1749 a Roman Jewish girl, Anna del Monte, is kidnapped and kept in isolation to force her to conversion. In the exhibit, we have a golden ring with a profile of Pius VII. The ring opens with a very intricate mechanism and contains the inscription “Immanuel”. It may have belonged to someone who had been forced to conversion under Pius VII.

CPL: Can you describe the process of production of the panels?

DDC: We have many documents concerning the production of the panels. We know that until 1725 the Jewish Community commissioned them to various artisans, scribes, and decorators. Often the Rabbi laid out the general concept and then hired copyists and miniaturists. After 1730 the community begins to hire a general contractor who coordinates the entire production and selects the personnel. Contractors were often members of the Jewish community with a political role and a relation with the Papal bureaucracy.

CPL: Were the craftsmen Jewish?

DDC: Usually the copyist who realized the Hebrew lettering was Jewish. As it happened for many illuminated Hebrew prayer books however, the miniaturist and the Latin copyist were often Christian, but at times Jewish.

CPL: Did the Jewish community pay all the expenses for these productions?

DDC: Yes and they were quite substantial. This was a matter of “onore e onere” (honor and onus) and the community invested a great deal of resources to pay proper homage to the Pontifex.

CPL: Did this inaugural act play a role in the way Roman Jews established a relation with the new Pope?

DDC: Obviously there was a pressure in that sense but there is no evidence that the grandiosity of the production helped a more benevolent attitude of the Popes. On the contrary, to marvelous presentations correspond some of the harshest Papal treatment of the Jews. This is the case for Benedict XIV and Pius VI.

CPL: What other sources were used to contextualize the panels in the exhibition?

DDC: One of our main sources is the work of Francesco Cancellieri, who, in 1802, collected chronicles and other documents of the Papal installations. We also used etchings of the Roman Baroque parades, through which we can visualize the environment and the spirit for which these panels were created.

CPL: The visit of Pope Benedict XVI is surrounded by controversy and yet the Jewish Community is devoting remarkable energy and resources to welcome him.

DDC: This is the first time that a Pope visits a Jewish Museum recognizing the history of the Jews of Rome, which is so entangled with that of Christian Rome. I think it is a great honor. This is a very Roman museum. Who has been in Rome longer than the Jews and who, better than the Pope, represents that history?